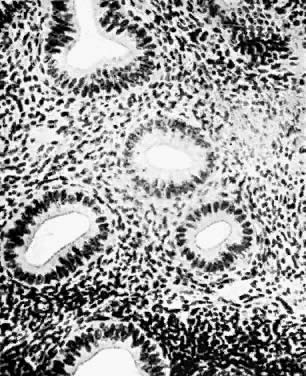

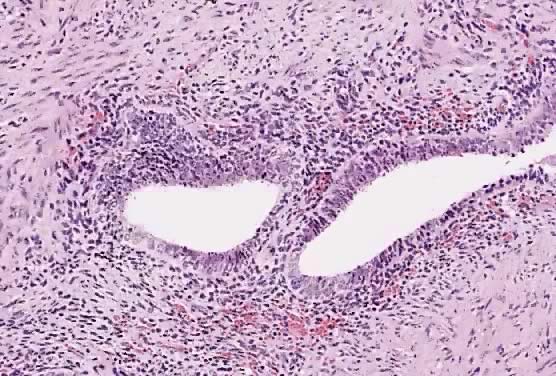

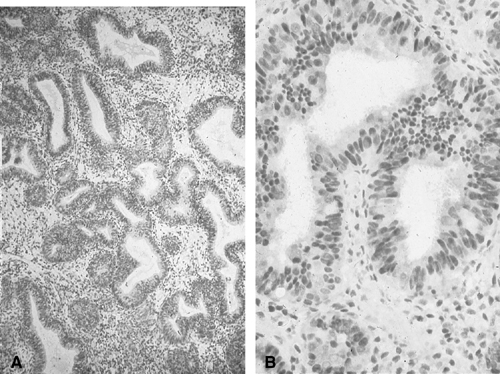

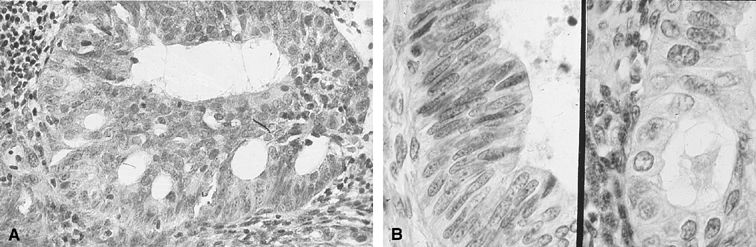

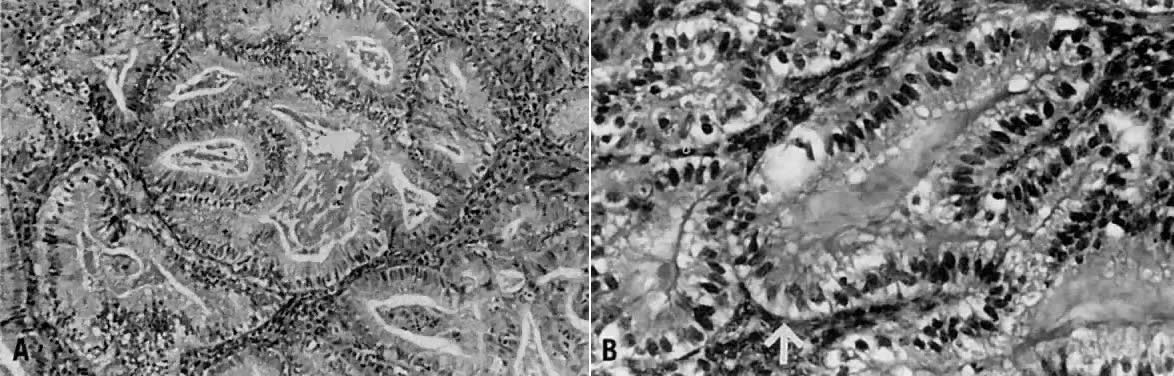

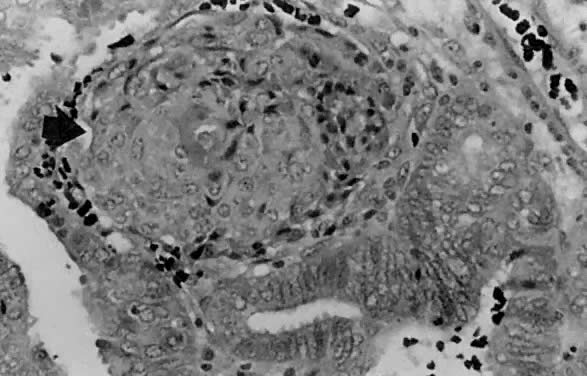

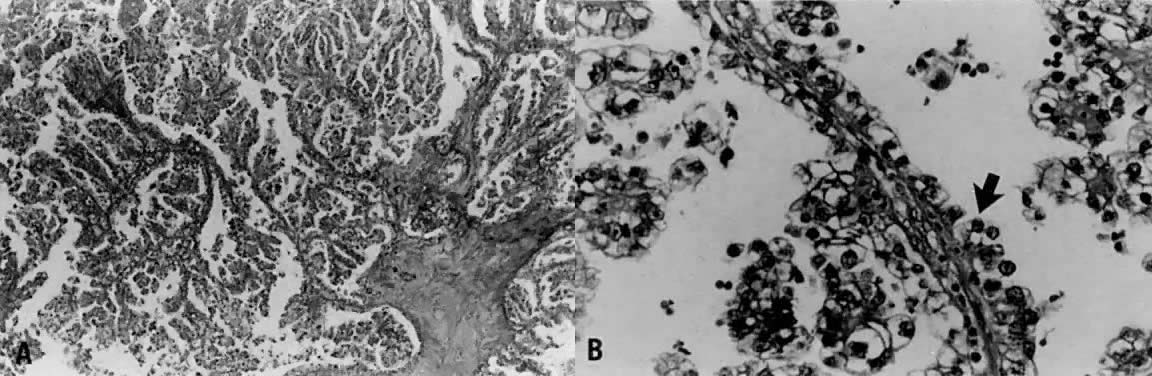

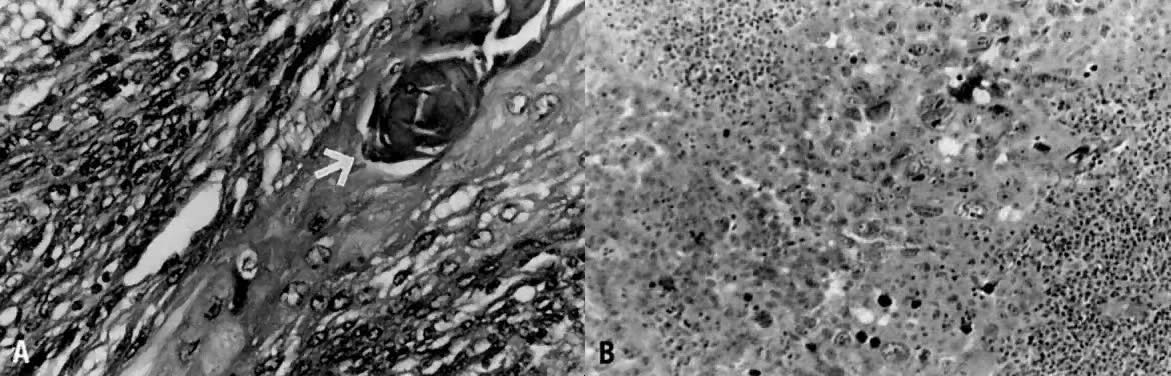

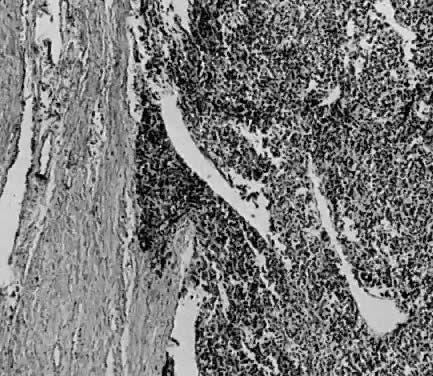

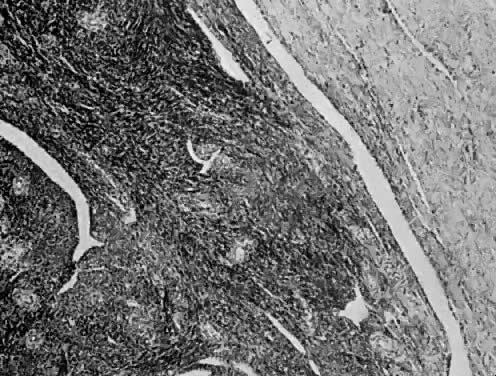

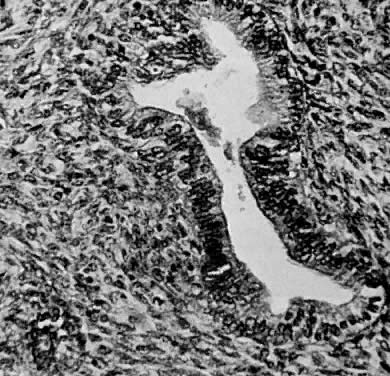

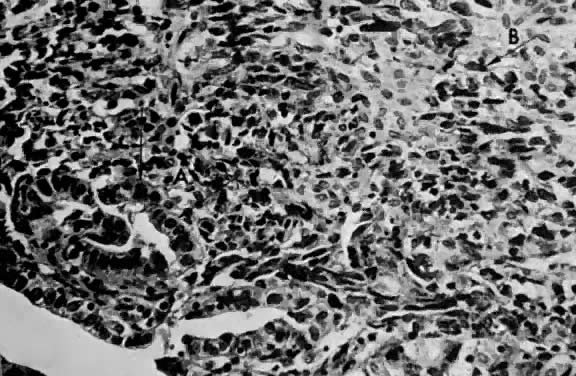

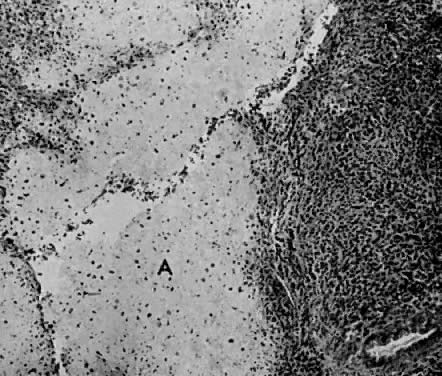

Fig. 1. A. Early proliferative endometrium (days 3–6).

Surface epithelium is intact. Glands are straight and tubular without

mitotic figures or pseudostratification. This normal endometrium was exposed

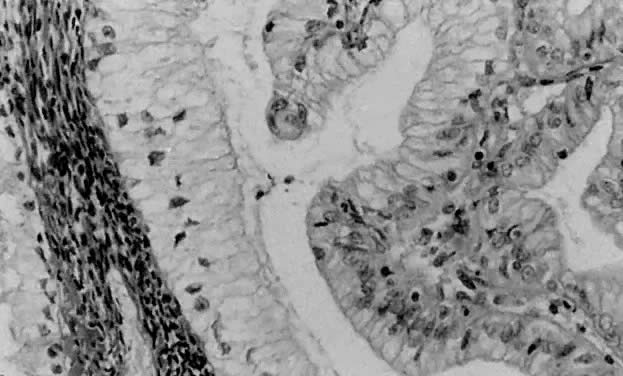

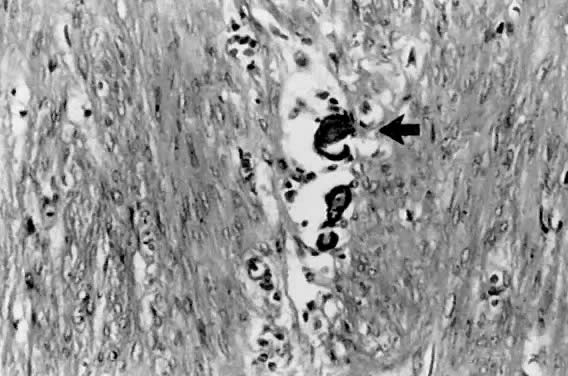

only to estrogen stimulation at the time of biopsy. B. Late secretory

endometrium (days 25–26) in a normal menstrual cycle. Tissue has

been predominantly stimulated by progesterone for 11 to 12 days. Glands

are convoluted and have expended most of their secretory products. The

stroma has undergone an extensive decidual reaction. Volume

4, Chapter 14

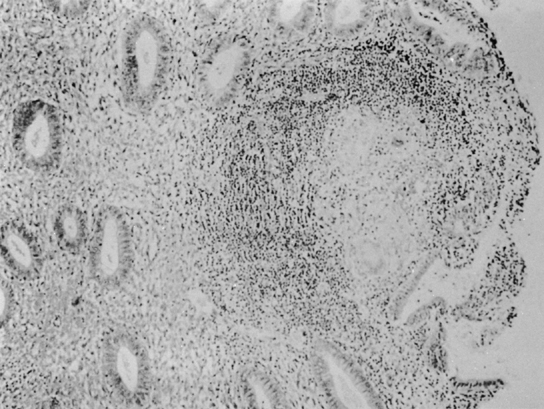

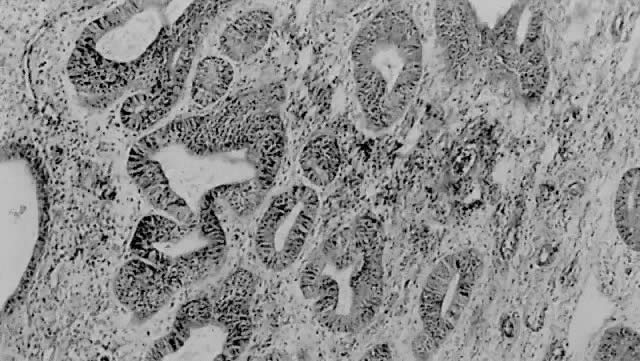

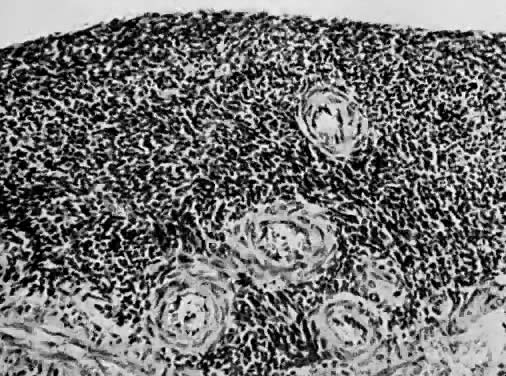

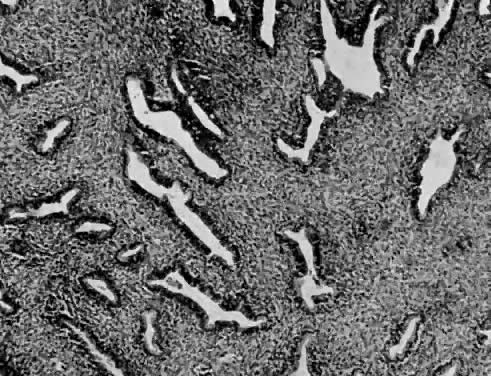

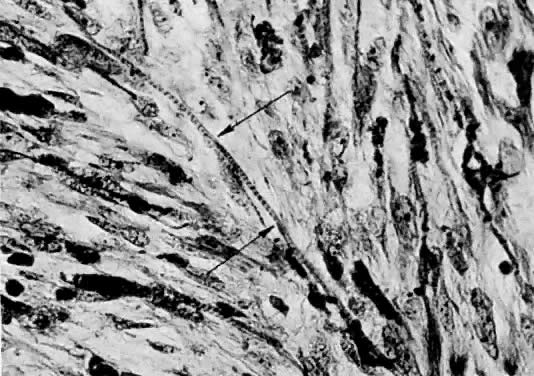

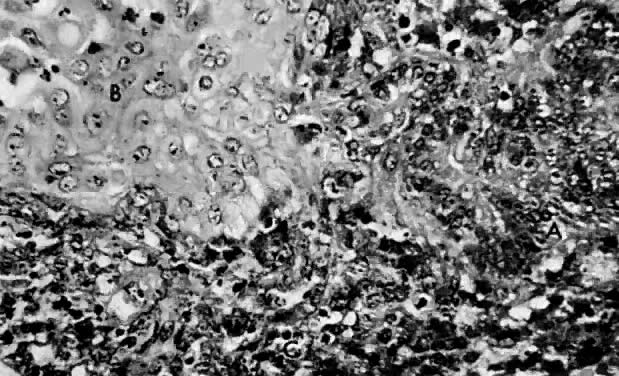

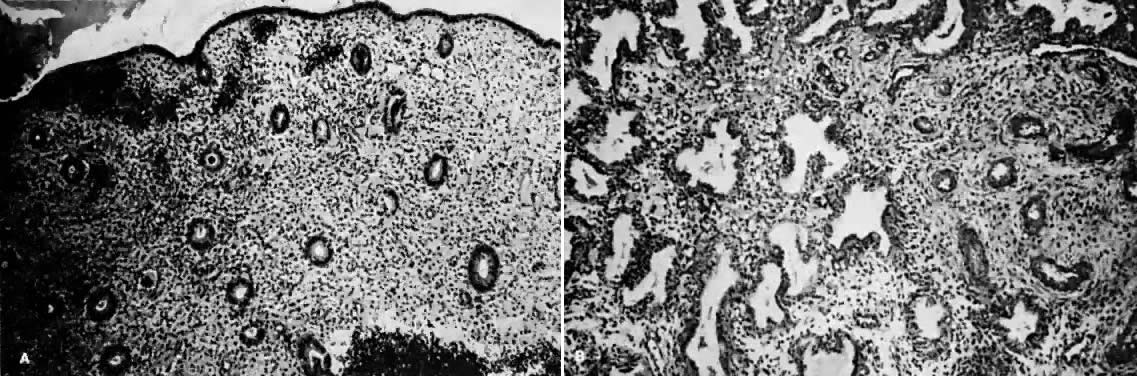

Fig. 1. A. Early proliferative endometrium (days 3–6).

Surface epithelium is intact. Glands are straight and tubular without

mitotic figures or pseudostratification. This normal endometrium was exposed

only to estrogen stimulation at the time of biopsy. B. Late secretory

endometrium (days 25–26) in a normal menstrual cycle. Tissue has

been predominantly stimulated by progesterone for 11 to 12 days. Glands

are convoluted and have expended most of their secretory products. The

stroma has undergone an extensive decidual reaction. Volume

4, Chapter 14