Preparation

After adequate anesthesia, the patient is placed into Allen stirrups with the thighs roughly parallel to the floor and the heels comfortably resting on the foot rests. The patient’s toe, knee, and opposite shoulder are aligned in a straight line. The bladder is emptied, and a Foley catheter is left indwelling. An appropriate uterine manipulator is used to mobilize the uterus.

Access and Exploration

Our team uses the open laparoscopy approach for primary access and three secondary access points drawn along the line of an imaginary Pfannenstiel incision for manipulation. Exploration of the pelvis and abdomen is the first step in the operation. This includes systematic exploration of the upper abdomen, the diaphragm, liver and gallbladder, appendix, omentum, pelvic organs, and cul-de-sac. After exploration, the uterus and adnexa are freed from adhesions if present.

Anterior Dissection and Development of the Bladder Flap

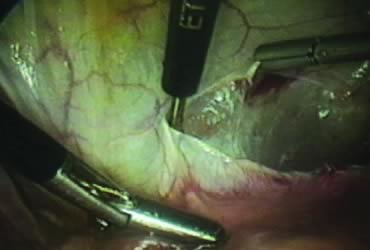

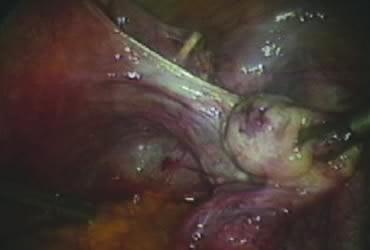

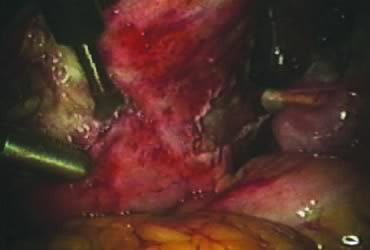

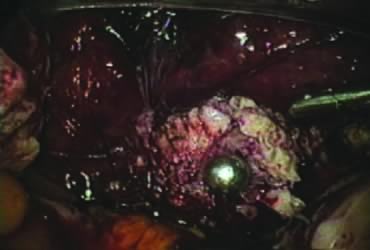

The right round ligament is held in its midportion, coagulated with bipolar forceps, and cut (Fig. 1). The anterior leaf of the right broad ligament is incised parallel to the uterus, and the incision is curved medially over the cervix (Fig. 2). The same two steps are repeated on the left side, and the incisions are connected (Fig. 3). The bladder flap is mobilized out of the surgical field by cutting the cervicovaginal septum, as needed. Coagulation and cutting the superficial upper portions of the lateral vesicouterine ligaments or bladder pillars completes the dissection.

|

Posterior Dissection

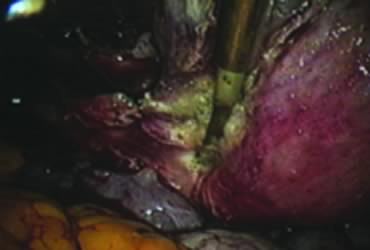

The right ovary is held with the three-prong grasper stretching and exposing the utero-ovarian ligament, which is coagulated and cut in its midportion (Fig. 4). The posterior leaf of the right broad ligament is incised downward to the level of the insertion of the uterosacral ligament in the cervix. The same two steps are repeated on the opposite side and the two sides are connected (Fig. 5).

|

Isolation of the Adnexa

A window is created in an areolar avascular area of the broad ligament with gentle blunt dissection. The adnexal structures above the window are coagulated (or sutured) and cut, isolating the adnexa and detaching it from the uterus (Fig. 6). The procedure is repeated in the contralateral side.

Securing Uterine Vessels

In supracervical hysterectomy, only the ascending branch of the uterine artery is skeletonized and secured preferably with a stitch (Fig. 7). The tissues medial to the stitch are coagulated (to prevent back flow) and cut (Fig. 8). The same steps are repeated on the opposite side.

|

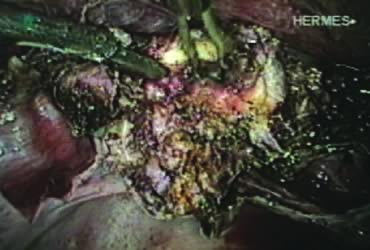

Amputation of the Uterus and Ablation of the Endocervix

After ligating both uterine arteries, the uterus becomes pale. At this time, the uterine body may be divided longitudinally using a shielded knife down to the cervix to facilitate morcellation. Each half is detached separately from the cervix 0.5 to 1 cm below the uterocervical junction and stored in the left upper abdomen. Alternatively, amputation of the uterine body off the cervix may be carried out through coagulation and cutting (above the ligated artery) proceeding from lateral to medial. The process may be initiated from the right or the left side. Bleeding points in the cervical stump are secured (Fig. 9). The upper portion of the endocervical canal is ablated circumferentially with bipolar coagulation (Fig. 10). Initially the walls of the cervix and the edges of the peritoneum were drawn together with sutures. This step was omitted, however, after noting at second look that the pelvic peritoneum heals without adhesions in the absence of sutures.

|

Concomitant Adnexectomy

If indicated, salpingo-oopherectomy can be performed at this time.

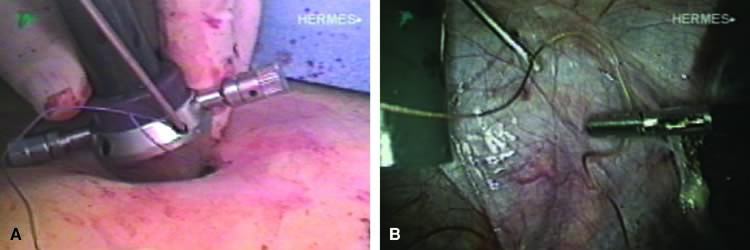

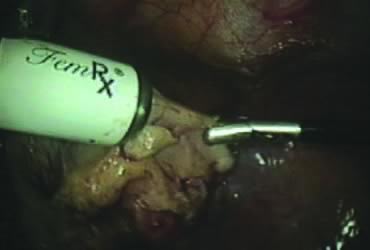

Removal of the Specimen

The stored uterus is removed using a mechanical morcellator, which is essentially a circular rotatory knife that slices the tissues longitudinally in the shape of a cylinder. The incision in the left lower quadrant is increased to 17 mm to accommodate a 15-mm trocar. The secure cone is mounted over the trocar, which is inserted into the abdomen.56 Sutures are passed through the tunnels of the secure cone to hold and stabilize the cannula in place (Fig. 11A). The mechanical morcellator is introduced through the 15-mm cannula, and morcellation is carried out in horizontal fashion by pulling the tissues into the morcellator from right to left to minimize the possibility of bowel injury (Fig. 12). When morcellation is complete, the trocar and the cone are removed, leaving the stay sutures in place. Tying these sutures together closes the surgical defect in the abdominal wall (Fig. 11B).56

|

Lavage, Inspection, and Closure

The pelvic cavity is irrigated, the operative sites are inspected, and small bleeding points are controlled, if needed. The enlarged incision in the left lower quadrant is closed under direct vision, as previously described. Secondary access trocars are removed under direct vision. The abdomen is deflated, and the primary access cannula is withdrawn. The open laparoscopy incision is closed in layers. The Foley catheter and the uterine manipulator are removed, and the operation is completed.