There has been great controversy and confusion in the literature when discussing

the dermatoses that are unique to pregnancy. Many different

names have been used to define clinically similar disorders. Different

classifications have been proposed ever since the first article was written

by Besnier in 1904 (Table 2).12 TABLE 2. Dermatoses of Pregnancy

Classification | Synonyms |

Herpes gestationis | Pemphigoid gestationis |

Pruritic uricarial papules and plaques of pregnancy | Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy |

| Toxemic rash of pregnancy |

| Toxic erythema of pregnancy |

| Late onset prurigo of pregnancy |

Cholestasis of pregnancy | Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy |

| Obstetric cholestasis |

| Prurigo gravidarum |

| Jaundice of pregnancy |

Impetigo herpetiformis | |

Prurigo of pregnancy | Early onset prurigo of pregnancy |

Papular dermatitis of pregnancy | |

Pruritic folliculitis of pregnancy | | Polymorphic Eruption of Pregnancy Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy (PEP) was first described by Lawley in 197912A as pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy (PUPPP). Both

PEP and PUPPP are terms that are interchangeably used, with PEP being

preferred in the current literature. PEP is the most common of the dermatoses

unique to pregnancy, with an incidence of 1 in 160. Seventy-five

to eighty-five percent of cases occur in primigravidas, who experience

an abrupt pruritic onset in the third trimester of pregnancy, most

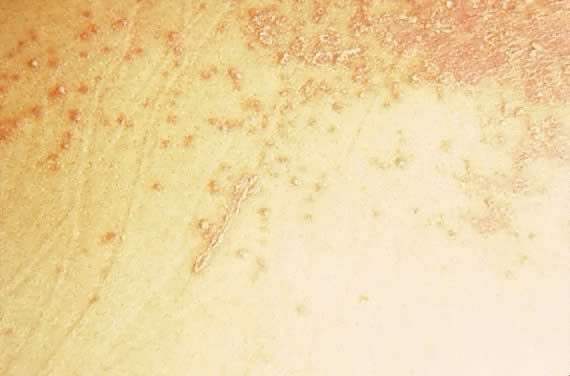

commonly in the 35th to 39th week of gestation or immediately postpartum.13 The eruption begins on the abdomen along the striae distensae, sparing

the umbilical and immediate periumbilical area (Figs. 7 and 8).14 This is in contrast to pemphigoid gestationis, in which the majority of

cases arise in the umbilical area. PEP may spread to the thighs, buttocks, and

extremities, but facial involvement is rare. As the name implies, the

skin manifestations are quite variable. These include vesicular, target-like, annular

or polycyclic papules or plaques that become

confluent over time (Figs. 9 and 10). In a recent study by Aronson and colleagues, three categories were defined15: type I, urticarial papules and plaques; type II, nonurticarial erythema, papules, or

vesicles; and type III, a combination of types I and II. The

cause of PEP is unknown. One proposed theory is the rapid stretching

of the skin late in pregnancy; this hypothesis is supported by the

initial presentation of the eruption along the striae distensae. Increased

maternal and newborn weight gain lends support to this theory; there

is a higher incidence of PEP in twin pregnancies.14,16,17  Fig. 7. Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy: erythematous papules along the striae

distensae. Fig. 7. Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy: erythematous papules along the striae

distensae.

|

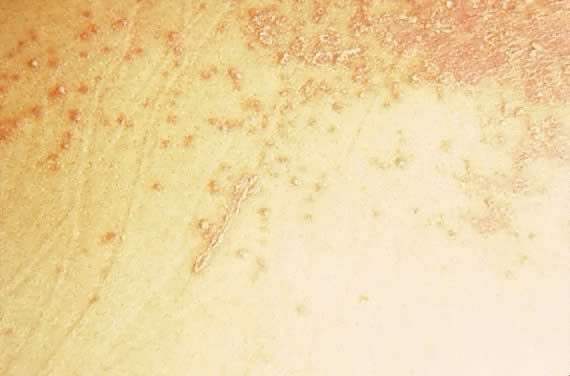

Fig. 8. Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy. Close-up view of Figure 7 showing the erythematous papules along the striae distensae. Fig. 8. Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy. Close-up view of Figure 7 showing the erythematous papules along the striae distensae.

|

Fig. 9. Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy morphology: coalescing urticarial papules

on the abdomen. Fig. 9. Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy morphology: coalescing urticarial papules

on the abdomen.

|

Fig. 10. Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy morphology: urticarial plaques on the

lateral surface of the upper thigh. Fig. 10. Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy morphology: urticarial plaques on the

lateral surface of the upper thigh.

|

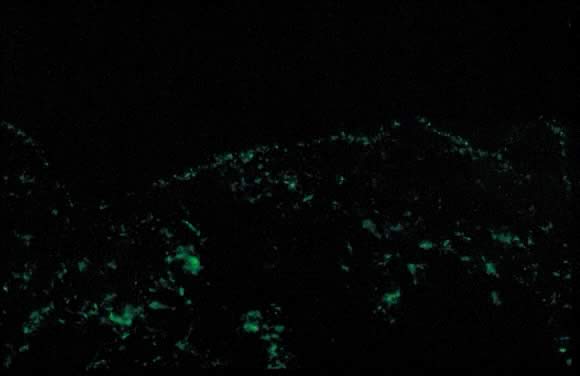

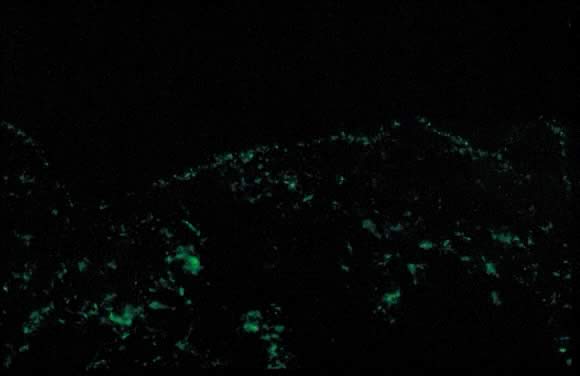

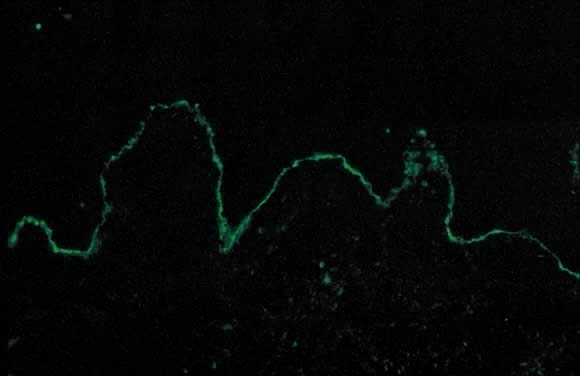

Fig. 11. Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy direct immunofluorescence: granular band

of C3 along the skin basement membrane zone. Fig. 11. Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy direct immunofluorescence: granular band

of C3 along the skin basement membrane zone.

|

Dermatopathology shows variable epidermal spongiosis with a perivascular

inflammatory infiltrate in the dermis composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and

a variable number of eosinophils. Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) is

negative for a linear band of C3 or IgG along the skin dermoepidermal

junction (DEJ); however, there have been reports of deposition

of IgM, C3, and IgA along the DEJ and blood vessels on DIF (Fig. 11).15,18 Differential diagnosis of PEP includes pemphigoid gestations (PG), contact

dermatitis, drug eruption, and viral exanthems. DIF of skin is necessary

to differentiate PEP from PG. The clinical course of PEP is usually

self-limiting, with a mean duration of 6 weeks. Pruritus is most

severe in the first week of onset, with spontaneous remission occurring

within days of parturition. Maternal and fetal mortalities are unaffected. PEP

rarely occurs in subsequent pregnancies; however, a few cases

of reoccurrence are reported in the literature.13 Treatment is symptomatic relief of pruritus with topical corticosteroids

of low- to mid-potency (use of ultra-high-potency corticosteroids for

an extensive period of time should be avoided) and pregnancy category

B antihistamines such as loratadine and cetirizine. Hydroxyzine and

diphenhydramine are pregnancy category C antihistamines that have been

used to relieve pruritus. In cases of severe pruritus unresponsive to

conservative measures, systemic corticosteroid administration or induced

delivery is considered. Pemphigoid Gestationis Initially described by Milton in 187218A as “herpes gestationis,” this condition was renamed pemphigoid

gestationis (PG) in 1982 due to its clinical and immunofluorescence

similarities with bullous pemphigoid.19 Both names continue to be used; pemphigoid gestationis is more common

in the United Kingdom.20,21 Estimated incidence of PG is 1 in 50,000 cases. Pemphigoid gestationis

most commonly occurs in the second or third trimester of pregnancy; about 25% of

cases may have an initial presentation immediately postpartum. Clinical

presentation is an abrupt onset of an intensely pruritic, urticarial

eruption on the trunk that forms tense vesicobullous lesions (Figs. 12 and 13). About 50% of cases have an initial presentation on the abdomen. Umbilical

involvement accounts for a significant number of cases of PG. As

in PEP, facial and mucosal membrane involvement is rare.21  Fig. 12. Pemphigoid gestationis: urticarial plaques in the periumbilical area with

tense blisters. Fig. 12. Pemphigoid gestationis: urticarial plaques in the periumbilical area with

tense blisters.

|

Fig. 13. Pemphigoid gestationis: close-up view of the tense blister in Figure 12. Fig. 13. Pemphigoid gestationis: close-up view of the tense blister in Figure 12.

|

Accurate diagnosis is crucial in light of the variable clinical course

of this disorder. Spontaneous resolution over weeks to months postpartum

is a common finding. About 75% of cases of PG present with flares immediately

postpartum. Recurrence in subsequent pregnancies with an earlier

onset and more severe clinical course is a common feature. Disease-free

pregnancies (i.e. “skip pregnancies”) with no cutaneous involvement in patients

with a history of PG have also been reported in the literature. There

have also been reports of PG flares occurring with menstruation and

use of oral contraceptives (25% of cases).20,21 PG is an autoimmune disorder caused by aberrant expression of the MHC II

class antigen on the chorionic villi of the placenta which triggers

an allogenic response to the placental basement membrane zone and subsequent

cross-reaction with maternal skin through the maternal decidua.22,23 There are reports of occurrence of PG in association with hydatidiform

mole and choriocarcinoma.24,25 Association of PG with other autoimmune diseases such as Graves' disease

has also been reported.26 Studies also show an increased incidence in HLA DR3 and DR4. HLA DR3 occurs

in the same percentage of white persons as in African American persons; however, the

percentage of DR4 is lower in African Americans, and

this may explain the rarity of PG in this population.27 Dermatopathology of PG shows subepidermal vesicle formation with focal

necrosis of keratinocytes. The dermis shows papillary edema and a perivascular

infiltrate consisting mainly of eosinophils and few lymphocytes. An

occasional finding on histopathology is the alignment of eosinophils

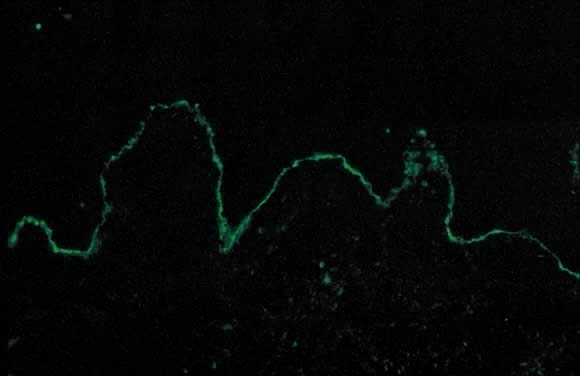

along the dermoepidermal junction. DIF shows a characteristic linear

band of C3 along the skin basement membrane zone of patients with

PG (Fig. 14). Linear C3 deposition on DIF is diagnostic of PG in the correct clinical

setting and is used to differentiate PEP from PG.28 Using this method, about 25% of cases also present with IgG deposits along

the basement membrane zone. Indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) demonstrates

the “PG factor,” which consists of circulating IgG

complement-fixing anti-basement membrane zone antibodies in serum of

patients with PG. Complement-activated IIF using monoclonal antibodies

directed against IgG1 demonstrates this factor in all PG patients.29 Clinically, titers of PG factor do not correlate with disease severity. The

PG factor is an IgG directed against a 180-kd hemidesmosomal (transmembrane) component

of the basement membrane zone.30 Electron microscopy also demonstrates the C3 and IgG deposits in the lamina

lucida.31  Fig. 14. Pemphigoid gestationis by direct immunofluorescence: linear band of C3 along

basement membrane zone of the skin. Fig. 14. Pemphigoid gestationis by direct immunofluorescence: linear band of C3 along

basement membrane zone of the skin.

|

In PG 10% of the infants born to affected mothers have skin lesions that

resemble PG; this is not the case with PEP. DIF and IIF studies done

on some of these infants are consistent with a diagnosis of PG.21 There has been considerable controversy in assessing fetal morbidity and

mortality associated with PG.32 Recent consensus on infant morbidity indicates a slight increase in prematurity

and small size for gestational age.33,34 The differential diagnosis of PG includes PEP, allergic contact dermatitis, and

drug eruption. A precise clinical history accompanied by diagnostic

tests such as histopathology and DIF help to distinguish among

these disorders. Treatment options include oral steroids (0.5 mg/kg daily) with

a possible increase in dose around the time of delivery to

avoid postpartum exacerbations. Other options include plasmapheresis, topical

corticosteroids, and antihistamines, all of which offer limited

benefit. After delivery, depending on breastfeeding status, alternative

treatments include dapsone, methotrexate, and cyclosporine.21 Impetigo Herpetiformis Impetigo herpetiformis is an acute eruption of pustular psoriasis during

pregnancy (most often presenting in the third trimester) in individuals

with no prior history of psoriasis. The first case was described by

Von Hebra in 1872; since then, about 100 cases have been reported.35 Clinical presentation involves sterile pustules on an erythematous base

that progressively become more confluent. This eruption commonly begins

on the flexural and inguinal skin and gradually spreads to the trunk

and involves the periumbilical skin (Figs. 15 and 16). Mucous membrane involvement of the oropharynx and the esophagus is also

seen. Impetigo herpetiformis is associated with constitutional symptoms

such as elevated temperature; gastrointestinal symptoms including

nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea; central nervous system symptoms such

as delirium; and musculoskeletal manifestation of tetany due to hypocalcemia.2,36 Recurrent eruptions in subsequent pregnancies usually present with an

earlier onset and more severe course.36 There have also been reports of exacerbation of this condition in affected

patients associated with later use of oral contraceptives.37  Fig. 15. Impetigo herpetiformis: diffuse erythematous papulosquamous eruption on

the trunk and extremities. Fig. 15. Impetigo herpetiformis: diffuse erythematous papulosquamous eruption on

the trunk and extremities.

|

Fig. 16. Impetigo herpetiformis: coalescing erythematous papules with silvery scale. Fig. 16. Impetigo herpetiformis: coalescing erythematous papules with silvery scale.

|

Early diagnosis and treatment is crucial. The few cases that have been

reported in the literature are associated with increased risk of fetal

mortality due to placental insufficiency, increased stillbirths, and

fetal abnormalities.36 Laboratory findings include evidence of leukocytosis, elevated erythrocyte

sedimentation rate, hypoalbuminemia, and hypocalcemia.2 Histopathology of skin biopsy specimens are consistent with pustular psoriasis. The

epidermis shows parakeratosis and elongation of rete ridges

with spongiform pustules of Kogoj. DIF, as in psoriasis, is negative.36 Treatment involves oral corticosteroids (with limited benefit), correction

of hypocalcemia, supportive measures, and antibiotics to prevent secondary

infections. Termination of pregnancy is usually curative.36,37 Retinoids (isotretinoin) and light therapy are more effective means of

treatment that can be used postpartum. Cholestasis of Pregnancy Cholestasis of pregnancy was initially described by Svanborg38 and Thorling39 in 1954. Cholestasis of pregnancy has been referred to by many other names, including

prurigo gravidarum, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, jaundice

of pregnancy, and obstetric cholestasis. The etiology is

believed to be multifactorial, and the condition occurs in 0.02% to 2.4% of

pregnancies. Studies show an increased incidence among certain

ethnic groups, such as some South American Indians. There is also a seasonal

variation in the prevalence of this condition, with a higher incidence

in the winter months. Fifty percent of cases are believed to be

familial, and a higher association has been seen in twin pregnancies.40,41 Another possible factor that contributes to the pathogenesis of this condition

is the effect of estrogen and other female hormones on the metabolism

and secretion of hepatic bile.2,40 Cholestasis of pregnancy, as the name implies, occurs only in pregnancy (most

commonly during the third trimester) and resolves after delivery, with

a 40% to 60% rate of recurrence in subsequent pregnancies. Clinical

presentation includes severe generalized pruritus with no primary

skin lesions. Secondary excoriations due to patient's scratching

may be the only skin findings. The extent and severity of pruritus fluctuates

until the time of delivery.40,42 Most severe pruritus occurs at night.9 About 20% of patients present with mild jaundice. This condition is the

second most common cause of gestational jaundice; viral hepatitis is

the most common cause.21 Laboratory values demonstrate elevated levels of bile salts, serum aminotransferases, alkaline

phosphatase, and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase.40,42 Because there are no primary skin lesions, skin biopsy results for histology

and DIF are normal. Pruritus greatly improves after delivery, and complete resolution is achieved

within a few days. In cases in which symptoms continue to persist, other

causes of cholestasis must be addressed.40 There have been reports of recurrence of symptoms with use of oral contraceptives.42 Differential diagnosis of pruritus in pregnancy should include parasitic

infections, allergic skin reactions, and other metabolic disorders. Fetal and maternal prognosis shows an increase in premature labor and low

birth weight. The fetus and the mother are at an increased risk of

intracranial and postpartum hemorrhage, respectively, due to deficiency

in vitamin K, which results in cases of prolonged fat malabsorption.21,42 Treatment options range from bed rest, a low-fat diet, and topical emollients

in mild cases to the use of agents such as cholestyramine, ursodeoxycholic

acid (UDCA), and S-adenosyl-L-methionine in more severe cases. Studies

show better outcomes for both mother and infant with administration

of UDCA compared with placebo. In severe cases, fetal monitoring

and cesarean section may be required.42 Prurigo of Pregnancy Prurigo of pregnancy was initially described by Besnier in 190412 as prurigo gestationis. It commonly occurs in the second to third trimester

of pregnancy as discrete erythematous excoriated papules on the

trunk and the extensor aspect of the lower extremities (Fig. 17). Incidence is roughly 1 in 300 pregnancies. Pathogenesis of this eruption

is believed to be the presence of atopy in the pregnant woman. Dermatopathology

of skin biopsy specimens shows parakeratosis and mild acanthosis

with a mixed inflammatory infiltrate of neutrophils and eosinophils

in the perivascular area. DIF results and laboratory values are

normal. There is no increased fetal or maternal risk, and treatment

is symptomatic relief with topical corticosteroids and antihistamines.2,21  Fig. 17. Prurigo of pregnancy: discrete erythematous excoriated papules on the extensor

surface of the arm. Fig. 17. Prurigo of pregnancy: discrete erythematous excoriated papules on the extensor

surface of the arm.

|

Papular Dermatitis of Pregnancy Papular dermatitis of pregnancy was initially described by Spangler in 196243 as a generalized papular erythematous and pruritic eruption with central

crust. The distribution is on the abdomen with spread to the extremities. An

increased level of urine hCG and a decrease in the urinary estriol

level, in combination with a significant increase in fetal morbidity

and mortality, was initially described. Many believe that papular

dermatitis of pregnancy and prurigo of pregnancy are similar entities. Histopathology

and DIF findings are similar. The high fetal risk initially

reported by Spangler43 has not been reproducible in other studies.44 Pruritic Folliculitis of Pregnancy Pruritic folliculitis of pregnancy was first described by Zoberman and

Farmer in 1981.45 Onset of eruption most commonly occurs in the second or third trimester

of pregnancy as small erythematous papules around follicles. The eruption

is typically monomorphic with distribution on the trunk and extremities (Fig. 18). Histopathology resembles a folliculitis, and the DIF is negative. Differential

diagnosis involves papular dermatitis or steroidinduced acne. The

fetus is unaffected, and the treatment is topical benzoyl peroxide.2,45  Fig. 18. Pruritic folliculitis of pregnancy: erythematous papules centered around

hair follicles on the back. Fig. 18. Pruritic folliculitis of pregnancy: erythematous papules centered around

hair follicles on the back.

|

|