Chapter 2

Anatomy of the Ureter

Anatomy of the ureter relevant for the laparoscopic hysterectomy in an uncomplicated case

What follows is a description of normal anatomy (Figure 1). It may not be relevant in instances where the anatomy is obviously disturbed by existing uterine or pelvic pathology. Examples include a cervical or large broad ligament fibroid, severe endometriosis with gross alteration of the pelvic anatomy, multiple prior surgical interventions or severe pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). In such cases the surgeon may feel the need for preoperative ureteric stenting. However in senior author’s opinion, this places the ureter in a situation of increased vulnerability. As noted on numerous occasions in the textual matter of this book and vividly illustrated in the videos, staying central and close to the uterine body is protective of the ureters. This is a reasonable course of action as the pathology of interest occupies the central position in the pelvis. It is a matter of record that other surgeons prefer to do ureteric dissection prior to commencing hysterectomy. The senior author of this book does not.

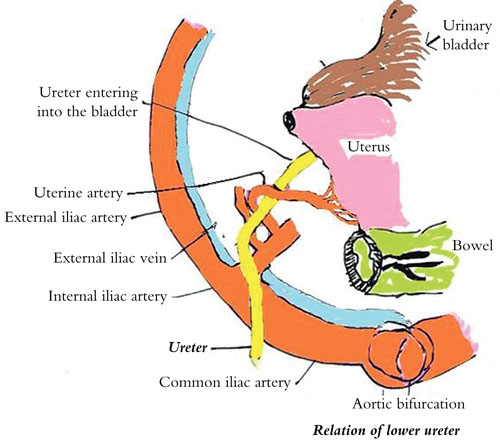

Figure 1 Normal anatomy of the ureter

In the majority of the patients, the course of the ureter is easily demarcated from the level of the pelvic brim. In general the ureter is seen crossing the external iliac vessels from lateral to medial at the base of the infundibulopelvic ligaments. It further traverses down along the lateral pelvic wall anterior and medial to the internal iliac artery. It then courses medially and can be seen disappearing in the ureteric tunnel 1–1.5 cm lateral to the uterosacral insertion. Anatomically the ureter is 1–1.5 cm away from the vaginal fornices before it enters the bladder trigone. In an uncomplicated case of laparoscopic hysterectomy, it is the terminal part of the ureter near the fornices and at the level of insertion into the bladder as well as the part of the ureter at the base of the infundibulopelvic ligament that are at risk of the injury during the surgical process owing to either direct trauma from scissors leading to transection or thermal injury from energy source dispersion if the early protective measures for the ureter are inadequate.

How to avoid ureteric injury during laparoscopic hysterectomy?

In an uncomplicated case of laparoscopic hysterectomy the ureters always remain laterally away from the operative area if one performs the following.

- From the beginning to the end of the surgery the vaginal assistant is instructed to push the uterine fundus cephalad.

- Adequate dissection of the bladder beyond the anterior fornix which is demarcated by the bulge of the manipulator guard is mandatory.

- Dissection of the posterior leaf of the broad ligament on either side as described earlier places the ureter in a more lateral position and away from the operating field.

If the surgeon uses the three principles listed above, the distance of the ureter from the actual point of the coagulation of the uterine pedicle and its vessels increases from 1.5 cm to 4–5 cm. When the ureters are displaced laterally in this manner, an adequate length of the uterine vessel is visible to coagulate.

As far as possible ureteral injury while doing salpingo-oophorectomy is concerned, the surgeon must hold the adnexa with a grasper and pull it towards the anterior abdominal wall more towards the midline in order to have good traction on the infundibulopelvic ligament. Cauterization of the ligament is carried out adjacent to the adnexa in order to avoid thermal spread to the ureter at the base of the ligament.