This chapter should be cited as follows:

Ciccarone F, Dababou S, Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.419633

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Gynecology Module

Volume 10

Ultrasound in gynecology

Volume Editors:

Professor Antonia Testa, Agostino Gemelli University Hospital, Rome, Italy

Professor Simona Maria Fragomeni, Agostino Gemelli University Hospital, Rome, Italy

Chapter

Ultrasound Differentiation of Malignant Myometrial Tumors, including STUMP and Sarcoma

First published: September 2025

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

Malignant myometrial pathology represents 3–7% of all uterine malignancies1 and involves a group of rare uterine tumors arising from mesenchymal tissue. According to the latest World Health Organization (WHO) classification, they include uterine leiomyosarcoma (LMS), low- and high-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma (ESS), undifferentiated uterine sarcoma, adenosarcoma, epithelioid sarcoma, and other rare histotypes.2,3 Smooth muscle tumors of uncertain malignant potential (STUMPs) are mesenchymal myometrial pathology that cannot be clearly classified as benign or malignant.2,3 Despite their rarity, malignant myometrial tumors are clinically significant due to their aggressive behavior and diagnostic challenges. Their clinical presentation and imaging findings often mimic those of benign leiomyomas, complicating preoperative diagnosis. However, recognizing the potential for malignancy is essential to plan surgery, prevent tumor dissemination and influence prognosis.

This chapter provides a detailed analysis of the ultrasound features of STUMPs and uterine sarcomas. It explores both common and uncommon sonographic patterns and outlines key imaging features that may support the differentiation from benign myometrial lesions. A brief overview is also provided on epidemiology and clinical features, histopathological and molecular characterization, alternative imaging modalities, treatment and prognosis.

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Among uterine sarcomas, LMS is the most common and aggressive subtype, arising from the smooth muscle of the myometrium and accounting for up to 60% of uterine sarcomas. ESSs are further divided into low-grade ESS, which tend to have an indolent course, and high-grade ESS, which behave more aggressively.4 Undifferentiated uterine sarcoma is another rare and highly malignant entity, which is characterized by poorly differentiated cells lacking specific stromal features.1 Adenosarcomas, tumors composed of benign epithelial components and malignant stromal elements, occupy a distinct category within uterine sarcomas.1 Finally, STUMPs represent a diagnostic gray-zone. These tumors exhibit atypical histopathological features that preclude classification as either benign leiomyomas or malignant leiomyosarcomas.2 STUMPs are extremely rare and their incidence is not well established.5

Uterine sarcomas account for less than 10% of all uterine corpus cancers, with an incidence ranging from 1.55 to 1.95 per 100 000 women per year.6 Uterine LMS is thought to arise de novo in most cases, while malignant transformation from a pre-existing leiomyoma is considered a rare event.7 The prevalence of unexpected sarcoma in women undergoing hysterectomy or myomectomy for a myometrial lesion ranges between 1 in 20008 and 1 in 350.9 Nevertheless, a correct identification of imaging features of malignancy is of utmost importance before surgery, to avoid procedures like morcellation that would lead to iatrogenic dissemination of occult malignancy. Managing uterine sarcomas remains challenging due to the difficulty in distinguishing benign from potentially malignant lesions preoperatively.10

Signs and symptoms of uterine malignant mesenchymal tumors may mimic benign leiomyomas such as heavy uterine bleeding, bulk symptoms, dysmenorrhea, infertility, pelvic pressure, abnormal vaginal discharge and intermenstrual bleeding.1,11 Most uterine sarcomas are symptomatic at presentation12,13 and occur in older women, with postmenopausal status being a significant risk factor, with an incidence four times higher than in younger women.7 Notably, a retrospective study found that ESS, more commonly occurs in younger, premenopausal women.13 The reported median ages of women at diagnosis are 50–56 years for LMS, 40–55 years for ESS, 55–60 years for undifferentiated uterine sarcoma (USS) and 41–48 years for STUMP.13,14 Black race is associated with a twofold increased risk of LMS compared to white women, while no similar association has been observed for other uterine sarcoma subtypes.15 Previous pelvic radiation therapy is a risk factor,16,17 along with obesity, nulliparity and excess endogenous estrogen, all of which are also associated with other uterine cancers.16,17

HISTOPATHOLOGICAL AND MOLECULAR FEATURES

Histological diagnosis is often controversial and frequently requires expert reassessment at referral centers. According to the WHO classification, STUMPs are defined as tumors that cannot be histologically diagnosed as unequivocally benign or malignant.18,19

The Stanford criteria of Bell et al.20 are commonly used to classify LMS, including the frequency of mitotic figures (≥ 10 per 10 high-power fields [HPFs]), extent of nuclear atypia and presence of coagulative tumor cell necrosis.18,19,20,21,22

The histopathological criteria remain inconsistent, hence immunohistochemistry and advanced molecular tests to detect fusion transcripts or assess mutation status may help in the diagnosis and to identify possible therapeutic targets.23,24

ULTRASOUND

Ultrasound remains the primary diagnostic tool for evaluating myometrial lesions, thanks to its cost-effectiveness, accessibility and reliable diagnostic performance, especially in expert centers.13,25 However, ultrasound has limited accuracy in characterizing smooth muscle uterine tumors, and no clinical or radiological criteria have demonstrated sufficient sensitivity and specificity to reliably distinguish malignant lesions, making preoperative diagnosis challenging. Findings on ultrasound examination should be reported using the terms, definitions and measurements provided by the Morphological Uterus Sonographic Assessment (MUSA) group.26 The use of MUSA terminology helps reduce intra- and interobserver variability, facilitates the assessment of treatment effects (both medical and surgical), enables comparison across different imaging modalities and ensures reproducibility and reliability across research protocols.

Ultrasound features of malignant myometrial pathology (STUMP and sarcoma)

Uterine sarcomas and STUMP are not frequently encountered, and most data on their ultrasound features stem from retrospective studies. Only a few emerging prospective studies have begun to provide more refined and potentially reliable diagnostic criteria.27,28

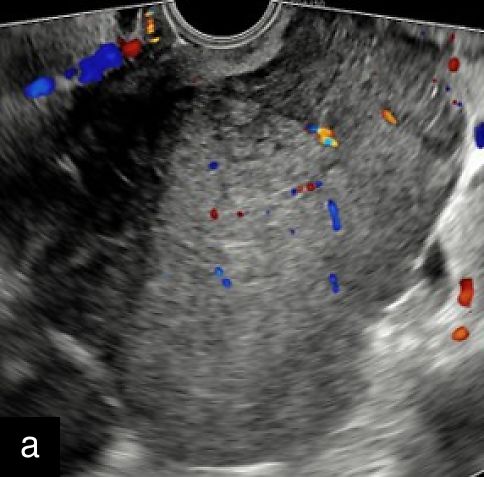

In 2019, an international group of experts conducted one of the first retrospective analyses of a relatively large cohort of histologically confirmed uterine sarcomas (n = 195; 116 LMS, 48 ESS and 31 USS), describing their most common ultrasound features.13 Malignant lesions appeared as large isolated solid masses (mean diameter, 91 mm) with inhomogeneous echogenicity of the solid tissue (77.4%), sometimes containing cystic areas (44.6%) (77% were irregular), mostly without fan-shaped shadowing or calcification (Figures 1 and 2). Although moderate-to-rich vascularization (color score 3–4) was common (67.9%), about one-third of sarcomas showed minimal or absent vascularization (color score 1–2), likely due to tumor necrosis (Figure 3). Notably, 20% were misclassified as benign, with ESS often showing normal endometrial appearance, regular margins and sparse vascularization, while USS displayed irregular margins, hemorrhagic cystic areas and absence of shadowing.13 One sarcoma was multilocular without solid components.13 The ‘cooked appearance’ of solid tissue, indicating necrosis, was observed in 21.7% of sarcoma cases13 but also appeared in leiomyomas and STUMPs, limiting its specificity.5 This sonographic feature refers to areas of inhomogeneous, hypoechoic solid tissue with absent internal vascularization, resembling the texture of cooked meat.

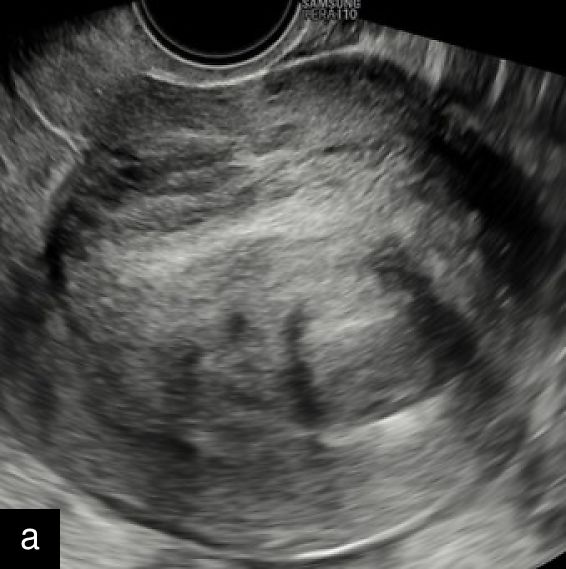

1

Transvaginal ultrasound images with Doppler evaluation of cases of STUMP. The images depict heterogeneous echotexture, irregular vascularization patterns and varying degrees of cystic and solid components.

|

|

|

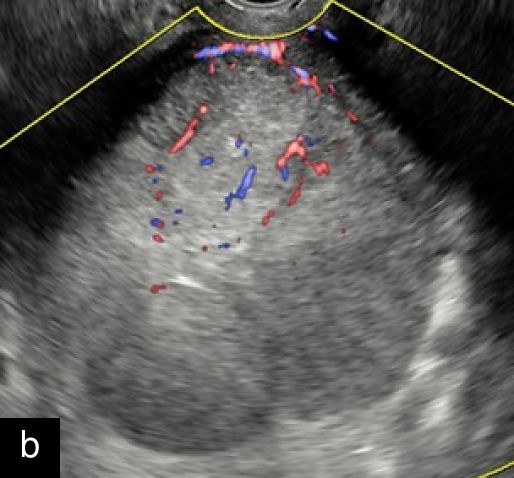

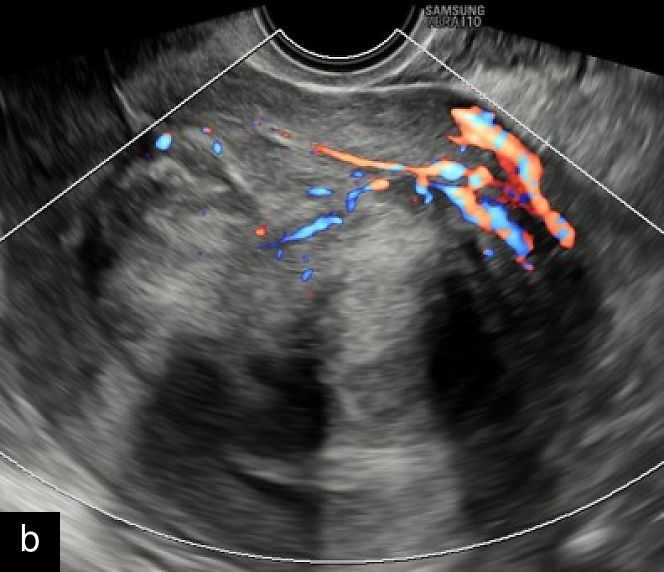

2

Transvaginal ultrasound images with color Doppler of uterine sarcoma, demonstrating heterogeneous echotexture and irregular margins. The Doppler assessment reveals variable vascularization patterns, ranging from moderate (a–b) to extensive (c) intralesional blood flow. Images (b) and (c) show the 'cooked appearance' of solid tissue, a sonographic feature defined by the lack of structure of the solid component and the absence of acoustic shadowing.

|

|

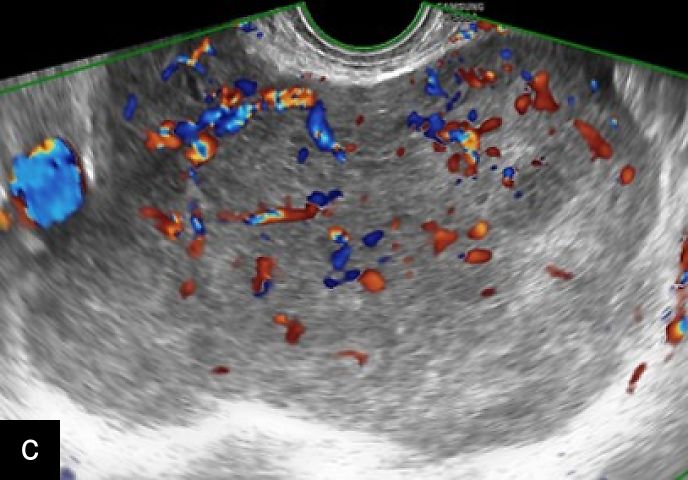

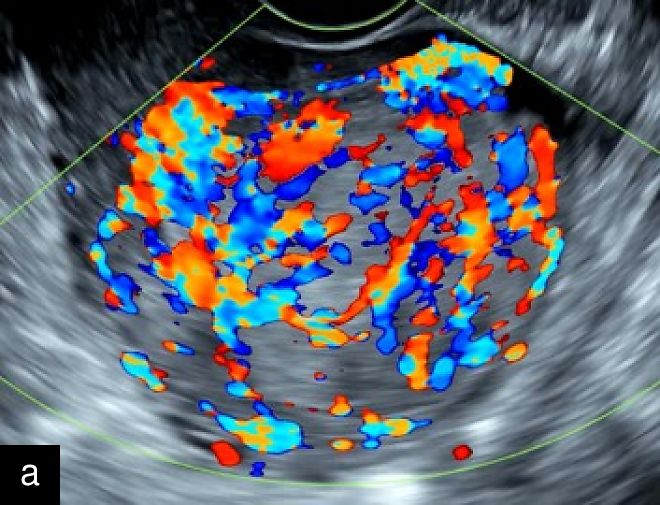

3

Transvaginal (a) and transabdominal (b) ultrasound images of uterine sarcoma. The lesion exhibits heterogeneous echotexture, irregular margins and peripheral vascularity on color Doppler. While uterine sarcomas are often highly vascularized, cases with lower vascularization can pose challenges in the differential diagnosis from benign myometrial lesions, such as atypical leiomyomas.

The presence of central necrosis, defined as irregular anechoic areas within an otherwise solid lesion, has also been described as a sonographic feature of uterine sarcomas in a separate retrospective study.29 Irregular intralesional cysts have been reported in the literature as a typical ultrasound feature of uterine sarcoma and are considered to reflect the end stage of central necrosis.13,29,30,31 A retrospective study assessing the level of interobserver agreement in identifying ultrasound features of malignant myometrial lesions found that the agreement was moderate for most features of uterine sarcoma, including irregular tumor borders, non-uniform echogenicity, cystic areas, central necrosis, absence of calcifications and high intralesional vascularity.29

A prospective single-center study by Ciccarone et al. evaluated, in 2268 women with myometrial lesions ≥ 3 cm, the accuracy of a clinical and ultrasound-based algorithm in predicting mesenchymal uterine malignancies, including STUMP.27 Among the 52 malignancies identified (23 LMS, 17 STUMP, seven USS and five ESS), lesions with irregular margins (48.1%), non-uniform echostructure (78.8%), mixed echogenicity (44.2%), moderate-to-rich vascularization (color score 3–4 (57.7%)) and irregular cystic areas (51.9%) were significantly more frequent.27 Moreover, malignant lesions were more often solitary (61.5%), lacked acoustic shadowing (50%) and appeared significantly larger (mean diameter, 107.1 mm, P <0.0001) compared to benign tumors.27 These sonographic patterns, validated in a large prospective cohort study, represent a key step toward improving preoperative risk stratification in clinical practice.

Heterogeneous echostructure along with moderate-to-high vascularity are useful ultrasound features that have been associated extensively with uterine sarcoma.13,29,32 Doppler ultrasound often reveals irregular vascular patterns with thin, scattered or dilated vessels, predominantly in marginal and central regions. LMS is also characterized by low resistance index (RI) (0.37 ± 0.03) and high peak systolic velocity (PSV) (71 cm/s vs 22.5 cm/s in leiomyomas).16,33

There are no specific ultrasound features of STUMPs, which are often described with imaging patterns similar to those of LMS. In a recent multicenter retrospective study (including 35 STUMPs, 50 LMS and 200 leiomyomas), STUMPs and LMS shared several features such as absence of normal myometrium, multilocular appearance, hyperechogenicity relative to the surrounding myometrium, and absence of posterior shadowing, echogenic areas and hyperechogenic rim.5

Interestingly, STUMPs were more strongly associated with FIGO Type 6–7, absence of internal shadows, and, in case of cystic areas, the presence of a smooth internal wall. A color score of 1 was more typical of leiomyomas, a color score of 2 was mainly reported in leiomyomas and STUMPs, while color score 4 was significantly associated with LMS. Combining both color score 3 and 4, it was found that both LMS and STUMPs had a high percentage of both circumferential and intralesional vascularization, compared to leiomyomas.5

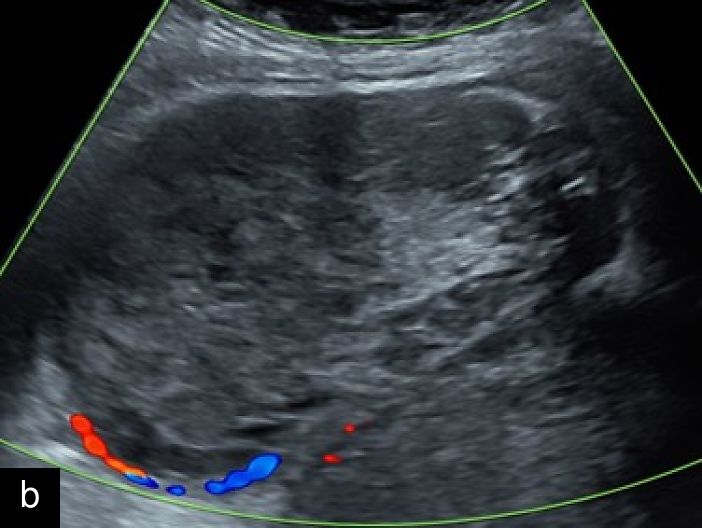

A retrospective series of 20 STUMPs further described most lesions as well-defined (85%), with non-uniform echogenicity, isoechoic (60%) or mixed echogenicity (30%) and microcystic anechoic areas (70%). No shadowing and no calcifications were reported. No calcifications or shadowing were observed, and the vascularization was predominantly poor-to-moderate (69%), with both circumferential and intralesional blood flow patterns being common (90%)28 (Figure 4).

|

|

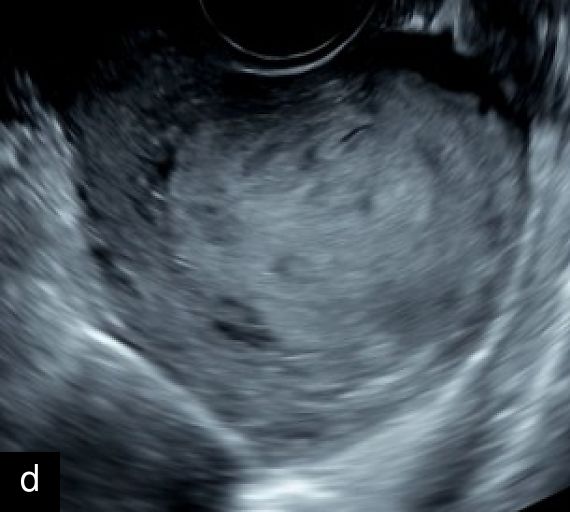

4

Grayscale (a) and color Doppler (b) transvaginal ultrasound images of a STUMP showing a heterogeneous mass with irregular echotexture. (b) Doppler imaging highlights scattered vascularization, with a color score of 3, indicating moderate vascularity and a potentially atypical neovascularization pattern.

Differentiating leiomyoma variants from uterine sarcoma/STUMP

The differentiation between benign and malignant uterine mesenchymal tumors represents one of the most complex challenges in gynecologic imaging. This difficulty arises when encountering atypical variants of leiomyomas (e.g. mitotically active, cellular or bizarre leiomyomas), which, despite their benign nature, may exhibit ultrasound features typically associated with malignancy. Among these, the most concerning findings include cystic areas, rich vascularization, irregular or ill-defined margins and absence of acoustic shadowing34 (Tables 1 and 2, Figure 5).

1

Sonographic features suspicious of uterine mesenchymal malignancy.

Feature | Typical suspicious appearance | Clinical relevance |

Tumor size | > 8 cm | Frequent in LMS, STUMP and other sarcomas27 |

Margins | Irregular, ill-defined | |

Echogenicity | Heterogeneous, mixed, non-uniform | |

Cystic degeneration | Irregular cysts, hemorrhagic or microcystic areas | |

'Cooked' appearance | Inhomogeneous, hypoechoic with no internal vascularity | |

Posterior shadowing | Absent | |

Calcifications | Absent | Absence raises suspicion in large solid masses13 |

Vascularization (color score) | Moderate-to-high (color score 3–4) | |

Vascular pattern | Irregular, intralesional, circumferential | |

Lesion distribution | Solitary mass | More typical of malignant than benign lesions13 |

2

Diagnostic ultrasound features of uterine mesenchymal malignancies: main evidence from the literature.

Author, year | Study design | Ultrasound features | Clinical features |

Ciccarone, 202527 | Prospective | Irregular margins; non-uniform echostructure; color score 4; cystic areas; absence of shadowing; single lesion; tumor diameter > 8 cm. | AUB; age > 45; symptomatic |

Borella, 20245 | Multicenter retrospective | Absence of normal myometrium; multilocular structure; non-uniform echogenicity; irregular cystic areas; absence of shadowing; color score 3–4; intra- and circumferential vascularization. | Older/postmenopausal women; AUB; pelvic pressure |

De Bruyn, 202429 | Retrospective | Irregular tumor borders; non-uniform echogenicity; cystic areas; central necrosis; absence of calcifications and moderate-to-abundant intralesional vascularity. | AUB; postmenopausal women |

Ludovisi, 201913 | Retrospective | Isolated large solid masses; inhomogeneous echogenicity; cystic areas (usually irregular); usually not manifesting shadowing or calcifications; moderately or well vascularized. | AUB; postmenopausal women. |

AUB, abnormal uterine bleeding.

|

|

|

|

5

Sonographic features that raise suspicion for malignancy include: rich vascularization (a), presence of cystic areas (b), irregular or ill-defined margins (c) and absence of acoustic shadowing (d).

It is important to underline, however, that these features are not pathognomonic for malignancy. For example, high vascularization can also be present in benign tumors. In fact, a prospective study on 70 women with highly vascularized smooth muscle tumors demonstrated that the vast majority were benign (93%), with only 7% diagnosed as malignant.32 Therefore, vascularity alone is not sufficient to establish a diagnosis. Patient age, on the other hand, remains an important risk factor.13,27,32 The same study32 showed that age and ultrasound features combined can help improve diagnostic performance. In particular, women over 40 years with highly vascularized lesions, irregular margins and no visible endometrium are at higher risk of malignancy.32 Moreover, a large retrospective study involving 2075 patients undergoing myomectomy found that the probability of unexpected uterine sarcoma varies substantially with age, ranging from approximately 1 in 100 in women aged 75–79 years, to less than 1 in 500 in those under 30 years of age.35

Another key point to consider is that sarcomas and STUMPs are not always highly vascularized. Some may present with minimal or absent blood flow on Doppler, emphasizing the heterogeneity of these tumors and the limits of relying on vascularity alone.13

Finally, the traditional concern regarding rapid tumor growth as a sign of malignancy has been reconsidered. Recent studies have shown that growth patterns in leiomyomas are highly variable between individuals. A retrospective analysis found no reliable predictors of which tumors would grow or regress over time, and concluded that growth alone, whether fast or slow, should not be used as a sole indicator of malignancy.36

Ultrasound diagnostic algorithm

A recent prospective study stratified 2268 patients into different risk classes using a traffic light algorithm including sonographic and clinical variables. Among 52 malignancies (23 LMS, 17 STUMPs, seven USS and five ESS), LMS patients were typically postmenopausal and symptomatic, with abnormal uterine bleeding (55.8%) being the most common symptom.27 Key ultrasound findings included ill-defined borders, heterogeneous echogenicity, moderate-to-rich vascularization, a ‘cooked’ appearance, irregular cystic areas and solitary lesions. Multivariable analysis confirmed that age, tumor diameter > 8 cm, irregular margins and color score 4 were independent risk factors for malignancy, while the presence of acoustic shadowing acted as a protective factor.27 Based on these five key parameters, a predictive traffic light algorithm was developed, which provides a score that allows stratification of patients into different risk classes (Figure 6). This predictive model demonstrated a sensitivity of 98.1%, specificity of 58.3% and area under the receiver-operating-characteristics curve (AUC) of 0.87, reinforcing its diagnostic value. Compared to other scoring systems, this approach emphasizes a dynamic follow-up strategy based on risk classes.27 By prospectively validating this approach in a large, real-world population, the study represents a key contribution toward safer and more personalized decision-making in the evaluation of myometrial lesions.

6

Traffic light algorithm for risk stratification of myometrial lesions. The traffic light system integrates one clinical (age) and four sonographic parameters (lesion diameter >8 cm, irregular borders, color score 4 and absence of acoustic shadowing) into a predictive model for mesenchymal uterine malignancies. Based on the calculated probability of malignancy, patients are stratified into: low-risk class (green): predicted risk <0.39%; intermediate-risk class (yellow): predicted risk 0.40–2.2%; or high-risk class (red): predicted risk ≥2.3%. This stratification supports personalized decision-making, ranging from conservative follow-up to immediate surgical management.

Radiomics

Advances in radiomics and machine learning are further enhancing diagnostic precision. In the ADMIRAL pilot study, analysis of ultrasound radiomic features in 70 patients (20 sarcomas, 50 leiomyomas) achieved 85% accuracy, 80% sensitivity, 87% specificity and an AUC of 0.86.37 While still at an early stage, these technologies offer the potential to quantify objectively sonographic features that are currently assessed subjectively, enhancing reproducibility and interobserver agreement.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The distinction between benign uterine tumors and sarcomas remains a diagnostic challenge, hence other imaging techniques, serum markers and preoperative biopsy may help in the differential diagnosis in selected cases.

Magnetic resonance imaging

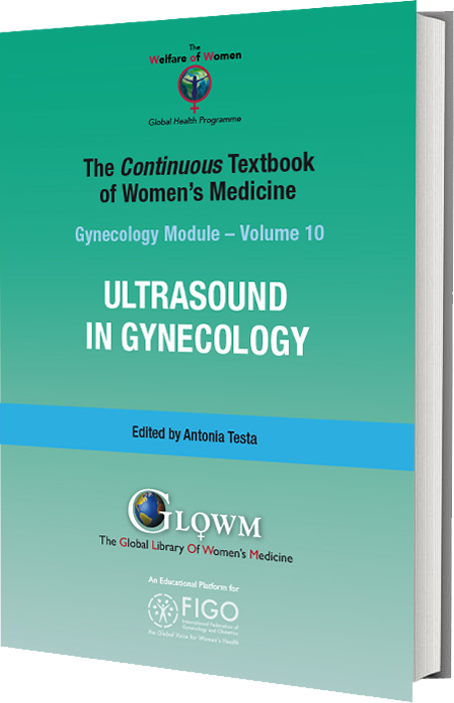

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may help in the preoperative evaluation of uterine masses, when ultrasound findings are inconclusive. MRI offers higher accuracy in soft-tissue contrast, a larger field of view, diffusion imaging and multiplanar capabilities.15 A recent consensus statement has provided a standardized approach to MRI assessment, emphasizing its role in distinguishing uterine sarcomas/STUMP from benign leiomyomas.15 Features suggestive of malignancy include irregular margins; heterogeneous and high signal on T2 weighted imaging; and hemorrhagic and necrotic changes, with central non-enhancement, hyperintensity on diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), and low values for apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC)15,25,39,40,41 (Figure 7). Diagnostic algorithms have been proposed to support MRI interpretation in differentiating between benign and malignant uterine lesions, and recent studies have explored the use of artificial intelligence to further enhance diagnostic accuracy.42,43,44 Emerging technologies, including radiomics and machine learning, show promise in improving diagnostic precision, although standardization and external validation remain essential.39,45

|

|

|

|

7

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of a STUMP. (a) Contrast-enhanced MRI showing heterogeneous enhancement of the mass. (b) T2-weighted MRI demonstrating a hyperintense lesion with heterogeneous signal intensity. (c) Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) highlighting areas of restricted diffusion. (d) Apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) map, showing low ADC values suggestive of increased cellularity, aiding in the differentiation of STUMP from benign leiomyomas and malignant leiomyosarcomas.

Lactate dehydrogenase

The preoperative imaging assessment when combined with clinical findings and serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels, could help to differentiate between leiomyosarcomas and degenerated uterine leiomyomas.46 While total LDH levels may increase in both benign and malignant uterine masses, specific isoenzymes, especially LDH3, LDH4 and LDH5, tend to be elevated in sarcomas, whereas LDH1 and LDH2 are typically reduced.47 A recent large retrospective study proposed a simple and effective risk model based on the combination of LDH3 and LDH1 isoenzymes, known as the uterine mass Magna Graecia (UMG) index.47 When applied to a cohort of 2254 patients with benign fibroids and 43 with confirmed sarcoma, the UMG index achieved 100% sensitivity and 99.6% specificity, with nine false positives among the 2211 benign cases and no false negative amongst 43 sarcomas. Its ability to distinguish between benign and malignant uterine masses suggests that, once prospectively validated, the UMG index could become a valuable tool in clinical practice, particularly useful when imaging is inconclusive.

Biopsy

In selected patients, biopsy can represent an additional tool to support differential diagnosis. However, the interpretation of biopsy specimens is not always straightforward. A retrospective French study involving centralized histopathological review reported a 14% rate of diagnostic discordance in patients initially diagnosed with sarcoma, mostly involving benign tumors mistaken for malignant, or vice versa. These data highlight the importance of expert pathology review and the potential consequences of diagnostic errors on patient management.48

Recent advances have improved the reliability of biopsy in this setting. ESGO/EURACAN/GCIG guidelines recommend that biopsy be utilized in specific scenarios, such as advanced-stage disease or cases in which hysterectomy is not immediately feasible.24 In such cases, image-guided core-needle biopsy (≥14–16G), performed in expert centers with access to advanced pathology, may provide useful preoperative information. Patients should always be informed of the possibility of false-negative results, particularly in the case of low-grade tumors, the histologic interpretation of which is inherently difficult.24,49

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS

The prognosis for patients diagnosed with uterine sarcoma is poor,50 with a 5-year survival rate of less than 50%.51 Conversely, most patients with STUMP experience favorable outcomes, although, in approximately 10% of cases, the lesion exhibits aggressive behavior.14

The optimal management of STUMP and uterine sarcoma varies widely due to differences in biological behavior and limited high-quality evidence. For STUMP, total hysterectomy with or without bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is generally recommended in women who do not wish to retain their fertility, while myomectomy may be considered in younger patients seeking fertility preservation.14,20,52,53 However, certain surgical techniques, such as unprotected morcellation (without the use of a containment bag), have been significantly associated with increased risk of recurrence (relative risk = 2.94; P = 0.001) and are considered independent predictors of recurrence.54 Despite these findings, the available literature shows no definitive survival benefit associated with more radical surgery.14,20,52,53 Postoperative management of STUMP remains inconsistent, with no established consensus on surveillance protocols. Reported recurrence rates range from 0% to 36%, with a mean of approximately 13%. In a large retrospective multicenter study including 87 patients, 18 cases (20.7%) recurred, 11 as LMS and seven as STUMP, with a mean time to recurrence of 79 months.52 Risk factors for recurrence and shorter recurrence-free survival included fragmentation or morcellation during surgery, epithelioid features, high mitotic count, Ki-67 ≥ 20%, progesterone receptor < 83% and diffuse p16 expression.52

In contrast, the standard treatment for early-stage uterine sarcomas is en-bloc total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy.10,55,56 Lymphadenectomy is not recommended unless macroscopic lymph node involvement is present.55 In premenopausal women with LMS, ovarian-sparing surgery may be considered, as evidence suggests that bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy does not improve survival.56 For early-stage LMS, adjuvant chemotherapy lacks strong supporting evidence;57,58 however, regimens including gemcitabine, docetaxel and doxorubicin may be considered for selected patients. In contrast, patients with low-grade (LG)-ESS may benefit from adjuvant hormonal therapy due to ER/PR receptor positivity, while data on high-grade (HG)-ESS and high-grade undifferentiated sarcoma (HG-USS) remain insufficient.4 Adjuvant radiotherapy, including external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) or intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT), may reduce pelvic relapse rates, particularly in LMS, but has no proven impact on overall survival.10

For advanced or recurrent sarcomas (LMS, HG-ESS, HG-USS, adenosarcomas), surgical cytoreduction is crucial, especially following a favorable response to chemotherapy. Prognosis varies by histological subtype: LMS are typically high-grade tumors with poor prognosis even when confined to the uterus, while LG-ESS has a favorable prognosis with potential for long-term survival. HG-ESS and HG-USS behave more aggressively, particularly in the absence of nuclear uniformity. Adenosarcoma is generally associated with a good prognosis unless there is myometrial invasion or sarcomatous overgrowth.1 Follow-up protocols depend on recurrence risk and tumor grade. For low-grade sarcomas, monitoring every 4–6 months for the first 3–5 years, followed by annual visits, is recommended, while high-grade sarcomas require closer surveillance: every 3–4 months for the first 2–3 years, every 6 months for the following 2–3 years and then annually.1

CONCLUSION

Uterine sarcomas and STUMP lesions, although rare, are of substantial clinical importance due to their potential aggressive behavior.

The preoperative differentiation between benign and malignant myometrial lesions remains a diagnostic challenge, in particular because of overlapping ultrasound features with variants of leiomyomas. Ultrasound remains the first-line diagnostic tool. Ultrasound features including irregular margins, heterogeneous echogenicity, absence of acoustic shadows and rich vascularization can raise suspicion, especially in symptomatic patients over 45 years of age. Predictive models based on algorithms, such as the traffic light algorithm, as well as emerging techniques, including radiomics and machine learning, are progressively improving diagnostic accuracy and risk stratification.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- Ultrasound remains the first-line diagnostic tool for assessing myometrial lesions due to its cost-effectiveness, accessibility and reliable diagnostic yield, although there are no established clinical or radiological criteria.

- The MUSA terminology is recommended for the description of myometrial findings on ultrasound examination. Using standardized terminology facilitates a uniform diagnostic approach and reduces intra- and interobserver variability.

- Differentiating between benign and malignant myometrial lesions can be challenging in the presence of atypical variants of leiomyoma (e.g. cellular, bizarre or mitotically active leiomyomas), which, despite their benign nature, may display ultrasound features commonly associated with malignancy.

- Typical ultrasound features of malignant mesenchymal tumors include irregular margins, heterogeneous echogenicity, absence of acoustic shadowing, rich vascularization and irregular cystic areas.

- The traffic light algorithm includes five key parameters (age, tumor diameter, margin regularity, color score and presence/absence of acoustic shadows) to stratify the patients into three risk classes (low, intermediate or high).

- Radiomics and machine learning algorithms applied to ultrasound and MRI are emerging tools for improved diagnostic precision and risk stratification.

- Diagnosis of malignant myometrial pathology requires a multidisciplinary approach of experts combining histological evaluation, immunohistochemistry and molecular profiling in referral centers.

- The prognosis for patients diagnosed with uterine sarcomas is poor. Conversely, most patients with STUMP experience favorable outcomes, although lesions may exhibit aggressive behavior.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) of this chapter declare that they have no interests that conflict with the contents of the chapter.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

REFERENCES

Mbatani N, Olawaiye AB, Prat J. Uterine sarcomas. Int J Gynaecol Obstet Off Organ Int Fed Gynaecol Obstet. 2018 Oct;143 Suppl 2:51–8. | |

WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Female Genital Tumours. 5th ed. International Agency for research on Cancer. | |

Croce S, Devouassoux-Shisheboran M, Pautier P, Ray-Coquard I, Treilleux I, Neuville A, Arnould L, Just PA, Belda MALF, Averous G, Leroux A, Mery E, Loussouarn D, Weinbreck N, Le Guellec S, Mishellany F, Morice P, Guyon F, Genestie C. Uterine sarcomas and rare uterine mesenchymal tumors with malignant potential. Diagnostic guidelines of the French Sarcoma Group and the Rare Gynecological Tumors Group. Gynecol Oncol.2022 Nov 1;167(2):373–89. | |

Leath CA, Huh WK, Hyde J, Cohn DE, Resnick KE, Taylor NP, Powell MA, Mutch DG, Bradley WH, Geller MA, Argenta PA, Gold MA. A multi-institutional review of outcomes of endometrial stromal sarcoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2007 Jun;105(3):630–4. | |

Borella F, Mancarella M, Preti M, Mariani L, Stura I, Sciarrone A, Bertschy G, Leuzzi B, Piovano E, Valabrega G, Turinetto M, Pino I, Castellano I, Bertero L, Cassoni P, Cosma S, Franchi D, Benedetto C. Uterine smooth muscle tumors: a multicenter, retrospective, comparative study of clinical and ultrasound features. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2024 Feb 1;34(2). | |

Tropé CG, Abeler VM, Kristensen GB. Diagnosis and treatment of sarcoma of the uterus. A review. Acta Oncol Stockh Swed. 2012 Jul;51(6):694–705. | |

Shah SH, Jagannathan JP, Krajewski K, O’Regan KN, George S, Ramaiya NH. Uterine sarcomas: then and now. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012 Jul;199(1):213–23. | |

Pritts EA, Parker WH, Brown J, Olive DL. Outcome of occult uterine leiomyosarcoma after surgery for presumed uterine fibroids: a systematic review. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015 Jan;22(1):26–33. | |

Health C for D and R. Laparoscopic Power Morcellators. FDA [Internet]. 2019 Sep 2; Available from: http://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/surgery-devices/laparoscopic-power-morcellators. | |

Ferrandina G, Aristei C, Biondetti PR, Cananzi FCM, Casali P, Ciccarone F, Colombo N, Comandone A, Corvo’ R, De Iaco P, Dei Tos AP, Donato V, Fiore M, Franchi null, Gadducci A, Gronchi A, Guerriero S, Infante A, Odicino F, Pirronti T, Quagliuolo V, Sanfilippo R, Testa AC, Zannoni GF, Scambia G, Lorusso D. Italian consensus conference on management of uterine sarcomas on behalf of S.I.G.O. (Societa’ italiana di Ginecologia E Ostetricia). Eur J Cancer Oxf Engl 1990. 2020 Nov;139:149–68. | |

Bucuri CE, Ciortea R, Malutan AM, Oprea V, Toma M, Roman MP, Ormindean CM, Nati I, Suciu V, Mihu D. Smooth Muscle Tumor of Uncertain Malignant Potential (STUMP): A Systematic Review of the Literature in the Last 20 Years. Curr Oncol. 2024 Sep 5;31(9):5242–54. | |

Oh J, Park SB, Park HJ, Lee ES. Ultrasound Features of Uterine Sarcomas. Ultrasound Q. 2019 Dec;35(4):376–84. | |

Ludovisi M, Moro F, Pasciuto T, Di Noi S, Giunchi S, Savelli L, Pascual MA, Sladkevicius P, Alcazar JL, Franchi D, Mancari R, Moruzzi MC, Jurkovic D, Chiappa V, Guerriero S, Exacoustos C, Epstein E, Frühauf F, Fischerova D, Fruscio R, Ciccarone F, Zannoni GF, Scambia G, Valentin L, Testa AC. Imaging in gynecological disease (15): clinical and ultrasound characteristics of uterine sarcoma. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Nov;54(5):676–87. | |

Gadducci A, Zannoni GF. Uterine smooth muscle tumors of unknown malignant potential: A challenging question. Gynecol Oncol. 2019 Sep;154(3):631–7. | |

Hindman N, Kang S, Fournier L, Lakhman Y, Nougaret S, Reinhold C, Sadowski E, Huang JQ, Ascher S. MRI Evaluation of Uterine Masses for Risk of Leiomyosarcoma: A Consensus Statement. Radiology. 2023 Feb 1;306(2):e211658. | |

Wojtowicz K, Góra T, Guzik P, Harpula M, Chechli?ski P, Wolak E, Stryjkowska-Góra A. Uterine Myomas and Sarcomas – Clinical and Ultrasound Characteristics and Differential Diagnosis Using Pulsed and Color Doppler Techniques. J Ultrason. 2022 Apr;22(89):100–8. | |

Denschlag D, Ulrich UA. Uterine Carcinosarcomas – Diagnosis and Management. Oncol Res Treat. 2018 Oct 13;41(11):675–9. | |

Dall’Asta A, Gizzo S, Musarò A, Quaranta M, Noventa M, Migliavacca C, Sozzi G, Monica M, Mautone D, Berretta R. Uterine smooth muscle tumors of uncertain malignant potential (STUMP): pathology, follow-up and recurrence. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2014 Oct 15 7(11):8136–42. | |

Richtarova A, Boudova B, Dundr P, Lisa Z, Hlinecka K, Zizka Z, Fruhauf F, Kuzel D, Slama J, Mara M. Uterine smooth muscle tumors with uncertain malignant potential: analysis following fertility-saving procedures. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2023 May 1;33(5). | |

Bell SW, Kempson RL, Hendrickson MR. Problematic uterine smooth muscle neoplasms. A clinicopathologic study of 213 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994 Jun;18(6):535–58. | |

Guntupalli SR, Ramirez PT, Anderson ML, Milam MR, Bodurka DC, Malpica A. Uterine smooth muscle tumor of uncertain malignant potential: a retrospective analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2009 Jun;113(3):324–6. | |

Ng JS, Han A, Chew SH, Low J. A Clinicopathologic Study of Uterine Smooth Muscle Tumours of Uncertain Malignant Potential (STUMP). Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2010 Aug 15;39(8):625–8. | |

Dundr P, Hojný J, Dvo?ák J, Hájková N, Vránková R, Krkavcová E, Berjon A, Bizo? M, Bobi?ski M, Bouda J, Bui QH, C?pîlna ME, Ciccarone F, Flídrová M, Fröbe A, Grabowska K, Halaška MJ, Hausnerová J, Jedryka M, Laco J, Kalist V, Klát J, Kolníková G, Ksi??ek M, Marek R, Mat?j R, Michal M, Michalová K, Ndukwe M, N?mejcová K, Petróczy D, Piatnytska T, Póka R, Poprawski T, Ry? J, Sawicki W, Sharashenidze A, Stolnicu S, Stružinská I, Šp?rková Z, Volodko N, Zapardiel I, Zikán M, Židlík V, Cibula D, Poncová R, Kendall Bárt? M. The Rare Gynecologic Sarcoma Study: Molecular and Clinicopathologic Results of A Project on 379 Uterine Sarcomas. Lab Invest. 2025;105(5):104092. | |

Ray-Coquard I, Casali PG, Croce S, Fennessy FM, Fischerova D, Jones R, Sanfilippo R, Zapardiel I, Amant F, Blay JY, Mart?n-Broto J, Casado A, Chiang S, Dei Tos AP, Haas R, Hensley ML, Hohenberger P, Kim JW, Kim SI, Meydanli MM, Pautier P, Abdul Razak AR, Sehouli J, van Houdt W, Planchamp F, Friedlander M. ESGO/EURACAN/GCIG guidelines for the management of patients with uterine sarcomas. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2024 Oct 1;34(10):1499–521. | |

Camponovo C, Neumann S, Zosso L, Mueller MD, Raio L. Sonographic and Magnetic Resonance Characteristics of Gynecological Sarcoma. Diagnostics. 2023 Mar 23;13(7):1223. | |

Van den Bosch T, Dueholm M, Leone FPG, Valentin L, Rasmussen CK, Votino A, Van Schoubroeck D, Landolfo C, Installé AJF, Guerriero S, Exacoustos C, Gordts S, Benacerraf B, D’Hooghe T, De Moor B, Brölmann H, Goldstein S, Epstein E, Bourne T, Timmerman D. Terms, definitions and measurements to describe sonographic features of myometrium and uterine masses: a consensus opinion from the Morphological Uterus Sonographic Assessment (MUSA) group. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015;46(3):284–98. | |

Ciccarone F, Biscione A, Robba E, Pasciuto T, Giannarelli D, Gui B, Manfredi R, Ferrandina G, Romualdi D, Moro F, Zannoni GF, Lorusso D, Scambia G, Testa AC. A clinical ultrasound algorithm to identify uterine sarcoma and smooth muscle tumors of uncertain malignant potential in patients with myometrial lesions: the MYometrial Lesion UltrasouNd And mRi study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 232, no. 1 (2025): 108-e1. | |

Cotrino I, Carosso A, Macchi C, Poma CB, Cosma S, Ribotta M, Viora E, Sciarrone A, Borella F, Zola P. Ultrasound and clinical characteristics of uterine smooth muscle tumors of uncertain malignant potential (STUMPs). Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020 Aug 1;251:167–72. | |

De Bruyn C, Ceusters J, Vanden Brande K, Timmerman S, Froyman W, Timmerman D, Van Rompuy A ?S., Coosemans A, Van Den Bosch T. Ultrasound features using MUSA terms and definitions in uterine sarcoma and leiomyoma: cohort study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol [Internet]. 2024 May;63(5):683–90. | |

Exacoustos C, Romanini ME, Amadio A, Amoroso C, Szabolcs B, Zupi E, Arduini D. Can gray-scale and color Doppler sonography differentiate between uterine leiomyosarcoma and leiomyoma? J Clin Ultrasound JCU. 2007 Oct;35(8):449–57. | |

Aviram R, Ochshorn Y, Markovitch O, Fishman A, Cohen I, Altaras MM, Tepper R. Uterine sarcomas versus leiomyomas: gray-scale and Doppler sonographic findings. J Clin Ultrasound JCU. 2005 Jan;33(1):10–3. | |

Russo C, Camilli S, Martire FG, Di Giovanni A, Lazzeri L, Malzoni M, Zupi E, Exacoustos C. Ultrasound features of highly vascularized uterine myomas (uterine smooth muscle tumors) and correlation with histopathology. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2022 Aug;60(2):269–76. | |

Kurjak A, Kupesic S, Shalan H, Jukic S, Kosuta D, Ilijas M. Uterine sarcoma: a report of 10 cases studied by transvaginal color and pulsed Doppler sonography. Gynecol Oncol. 1995 Dec;59(3):342–6. | |

Tu?ba K?nay SYE. Characteristics that distinguish leiomyoma variants from the ordinary leiomyomas and recurrence risk. Gulhane Medical Journal; 2022. | |

Brohl AS, Li L, Andikyan V, Obi?an SG, Cioffi A, Hao K, Dudley JT, Ascher-Walsh C, Kasarskis A, Maki RG. Age-Stratified Risk of Unexpected Uterine Sarcoma Following Surgery for Presumed Benign Leiomyoma. The Oncologist. 2015 Apr; 20(4):433–9. | |

Armbrust R, Wernecke KD, Sehouli J, David M. The growth of uterine myomas in untreated women: influence factors and ultrasound monitoring. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2018 Jan;297(1):131–7. | |

Chiappa V, Interlenghi M, Salvatore C, Bertolina F, Bogani G, Ditto A, Martinelli F, Castiglioni I, Raspagliesi F. Using rADioMIcs and machine learning with ultrasonography for the differential diagnosis of myometRiAL tumors (the ADMIRAL pilot study). Radiomics and differential diagnosis of myometrial tumors. Gynecol Oncol. 2021 Jun;161(3):838–44. | |

Sambri A, Caldari E, Fiore M, Zucchini R, Giannini C, Pirini MG, Spinnato P, Cappelli A, Donati DM, De Paolis M. Margin Assessment in Soft Tissue Sarcomas: Review of the Literature. Cancers. 2021 Apr 2;13(7):1687. | |

Sumi A, Terasaki H, Sanada S, Uchida M, Tomioka Y, Kamura T, Yano H, Abe T. Assessment of MR Imaging as a Tool to Differentiate between the Major Histological Types of Uterine Sarcomas. Magn Reson Med Sci. 2015;14(4):295–304. | |

Ravegnini G, Ferioli M, Morganti AG, Strigari L, Pantaleo MA, Nannini M, De Leo A, De Crescenzo E, Coe M, De Palma A, De Iaco P, Rizzo S, Perrone AM. Radiomics and Artificial Intelligence in Uterine Sarcomas: A Systematic Review. J Pers Med. 2021 Nov 11;11(11):1179. | |

Lin G, Yang LY, Huang YT, Ng KK, Ng SH, Ueng SH, Chao A, Yen TC, Chang TC, Lai CH. Comparison of the diagnostic accuracy of contrast-enhanced MRI and diffusion-weighted MRI in the differentiation between uterine leiomyosarcoma/smooth muscle tumor with uncertain malignant potential and benign leiomyoma. J Magn Reson Imaging JMRI. 2016 Feb;43(2):333–42. | |

Toyohara Y, Sone K, Noda K, Yoshida K, Kato S, Kaiume M, Taguchi A, Kurokawa R, Osuga Y. The automatic diagnosis artificial intelligence system for preoperative magnetic resonance imaging of uterine sarcoma. J Gynecol Oncol. 2024;35(3):e24. | |

Rosa F, Martinetti C, Magnaldi S, Rizzo S, Manganaro L, Migone S, Ardoino S, Schettini D, Marchiolè P, Ragusa T, Gandolfo N. Uterine mesenchymal tumors: development and preliminary results of a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) diagnostic algorithm. Radiol Med (Torino). 2023 Jul 1;128(7):853–68. | |

Lebar V, ?elebi? A, Calleja-Agius J, Jakimovska Stefanovska M, Drusany Staric K. Advancements in uterine sarcoma management: A review. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2025 Apr; 51(4):109646. | |

Malek M, Gity M, Alidoosti A, Oghabian Z, Rahimifar P, Seyed Ebrahimi SM, Tabibian E, Oghabian MA. A machine learning approach for distinguishing uterine sarcoma from leiomyomas based on perfusion weighted MRI parameters. Eur J Radiol. 2019 Jan;110:203–11. | |

Goto A, Takeuchi S, Sugimura K, Maruo T. Usefulness of Gd-DTPA contrast-enhanced dynamic MRI and serum determination of LDH and its isozymes in the differential diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma from degenerated leiomyoma of the uterus. Int J Gynecol Cancer Off J Int Gynecol Cancer Soc. 2002;12(4):354–61. | |

Di Cello A, Borelli M, Marra ML, Franzon M, D’Alessandro P, Di Carlo C, Venturella R, Zullo F. A more accurate method to interpret lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) isoenzymes’ results in patients with uterine masses. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2019 May;236:143–7. | |

Perrier L, Rascle P, Morelle M, Toulmonde M, Ranchere Vince D, Le Cesne A, Terrier P, Neuville A, Meeus P, Farsi F, Ducimetière F, Blay JY, Ray Coquard I, Coindre JM. The cost-saving effect of centralized histological reviews with soft tissue and visceral sarcomas, GIST, and desmoid tumors: The experiences of the pathologists of the French Sarcoma Group. PLoS ONE. 2018 Apr 5;13(4):e0193330. | |

Fischerova D, Planchamp F, Alcázar JL, Dundr P, Epstein E, Felix A, Frühauf F, Garganese G, Salvesen Haldorsen I, Jurkovic D, Kocian R, Lengyel D, Mascilini F, Stepanyan A, Stukan M, Timmerman S, Vanassche T, Ng ZY, Scovazzi U. ISUOG/ESGO Consensus Statement on ultrasound-guided biopsy in gynecological oncology. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2025 Apr 1;35(4):101732. | |

Zivanovic O, Jacks LM, Iasonos A, Leitao MM, Soslow RA, Veras E, Chi DS, Abu-Rustum NR, Barakat RR, Brennan MF, Hensley ML. A nomogram to predict postresection 5-year overall survival for patients with uterine leiomyosarcoma. Cancer. 2012 Feb 1;118(3):660–9. | |

Ruiz-Minaya M, Mendizabal-Vicente E, Vasquez-Jimenez W, Perez-Burrel L, Aracil-Moreno I, Agra-Pujol C, Bernal-Claverol M, Martínez-Bernal BL, Muñoz-Fernández M, Morote-Gonzalez M, Ortega MA, Lizarraga-Bonelli S, De Leon-Luis JA. Retrospective Analysis of Patients with Gynaecological Uterine Sarcomas in a Tertiary Hospital. J Pers Med. 2022 Feb 6;12(2):222. | |

Borella F, Cosma S, Ferraioli D, Ray-Coquard I, Chopin N, Meeus P, Cockenpot V, Valabrega G, Scotto G, Turinetto M, Biglia N, Fuso L, Mariani L, Franchi D, Vidal Urbinati AM, Pino I, Bertschy G, Preti M, Benedetto C, Castellano I, Cassoni P, Bertero L. Clinical and Histopathological Predictors of Recurrence in Uterine Smooth Muscle Tumor of Uncertain Malignant Potential (STUMP): A Multicenter Retrospective Cohort Study of Tertiary Centers. Ann Surg Oncol. 2022 Dec;29(13):8302–14. | |

Gupta M, Laury AL, Nucci MR, Quade BJ. Predictors of adverse outcome in uterine smooth muscle tumours of uncertain malignant potential (STUMP): a clinicopathological analysis of 22 cases with a proposal for the inclusion of additional histological parameters. Histopathology. 2018 Aug;73(2):284–98. | |

Di Giuseppe J, Grelloni C, Giuliani L, Delli Carpini G, Giannella L, Ciavattini A. Recurrence of Uterine Smooth Muscle Tumor of Uncertain Malignant Potential: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Cancers. 2022 May 7;14(9):2323. | |

Benson C, Miah AB. Uterine sarcoma – current perspectives. Int J Womens Health. 2017;9:597–606. | |

Seagle BLL, Sobecki-Rausch J, Strohl AE, Shilpi A, Grace A, Shahabi S. Prognosis and treatment of uterine leiomyosarcoma: A National Cancer Database study. Gynecol Oncol. 2017 Apr;145(1):61–70. | |

Bogani G, Fucà G, Maltese G, Ditto A, Martinelli F, Signorelli M, Chiappa V, Scaffa C, Sabatucci I, Lecce F, Raspagliesi F, Lorusso D. Efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy in early stage uterine leiomyosarcoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2016 Nov;143(2):443–7. | |

Pautier P, Floquet A, Gladieff L, Bompas E, Ray-Coquard I, Piperno-Neumann S, Selle F, Guillemet C, Weber B, Largillier R, Bertucci F, Opinel P, Duffaud F, Reynaud-Bougnoux A, Delcambre C, Isambert N, Kerbrat P, Netter-Pinon G, Pinto N, Duvillard P, Haie-Meder C, Lhommé C, Rey A. A randomized clinical trial of adjuvant chemotherapy with doxorubicin, ifosfamide, and cisplatin followed by radiotherapy versus radiotherapy alone in patients with localized uterine sarcomas (SARCGYN study). A study of the French Sarcoma Group. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol. 2013 Apr;24(4):1099–104. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards program CLICK HERE)