This chapter should be cited as follows:

Ciancia M, Sidoti G, et al., Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.419583

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Gynecology Module

Volume 10

Ultrasound in gynecology

Volume Editors:

Professor Antonia Testa, Agostino Gemelli University Hospital, Rome, Italy

Professor Simona Maria Fragomeni, Agostino Gemelli University Hospital, Rome, Italy

Chapter

Ultrasound Assessment of Pelvic Anatomy

First published: April 2025

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

Ultrasound is the diagnostic tool of choice for the study of normal female pelvic anatomy and the diagnosis of gynecological pathology.1 It is a non-invasive and easily accessible procedure, which is neither painful nor particularly expensive. The possibility of using color Doppler enables the analysis of vascularization, often essential for differential diagnosis and the characterization of pelvic pathology. Furthermore, a dynamic and interactive evaluation is possible by applying pressure and retraction movements of the endovaginal probe. This technique allows the operator to assess the mobility, elasticity and deformability of examined organs, as well as their tenderness, allowing for a more accurate and specific diagnosis by facilitating the mapping of painful pelvic areas through interaction with the patient.2

Transvaginal ultrasound, thanks to the use of high-frequency endocavitary probes, is ideal for an accurate morphological evaluation of pelvic organs, as most target organs are located near the vagina, regardless of the patient's body type. The endorectal approach is a viable alternative for studying female pelvic anatomy and should be considered when a transvaginal examination is not feasible, for example, in virgin patients, cases of severe vaginal stenosis or vaginismus, and in patients who have undergone radiotherapy or surgical treatments affecting the vagina.3

In some cases, the structures under examination may extend beyond the pelvis or may not be adequately visualized using the vaginal or rectal approach, making an abdominal approach necessary. Transabdominal ultrasound may also be useful in cases in which the uterus is closely aligned with the vaginal canal, as this positioning can make endocavitary evaluation with a transvaginal probe more challenging. Additionally, ureteral obstruction caused by endometriotic lesions or other neoplastic structures requires renal assessment by transabdominal ultrasound to evaluate possible hydronephrosis. Therefore, pelvic ultrasound evaluation should not be limited to the endocavitary approach but should also include, when necessary, the transabdominal approach, the two techniques being complementary.4

Advances in ultrasound technology have reduced the need for bladder distension to adequately visualize pelvic anatomy during abdominal scans. However, in certain patients, especially in pediatric or pubertal cases, a distended bladder filled with urine is often required for optimal visualization.5

PELVIC ANATOMY

A standardized scanning protocol ensures that the ultrasound examination is performed systematically and comprehensively. The recommended sequence in which the pelvic organs should be assessed during endocavitary ultrasound examination is the following:

- Vagina

- Bladder

- Cervix and uterus

- Endometrium

- Adnexa

- Parametrium

- Vesicouterine pouch and pouch of Douglas

- Rectum

- Retroperitoneum

Vagina

Ultrasound evaluation of the vagina and perineum is the first essential step in a pelvic ultrasound examination. Gently inserting the endocavitary probe into the vagina, the vaginal walls should be carefully visualized until the tip of the probe is positioned at the level of the anterior vaginal fornix, in order to identify any vaginal abnormalities and recognize their different ultrasound characteristics.

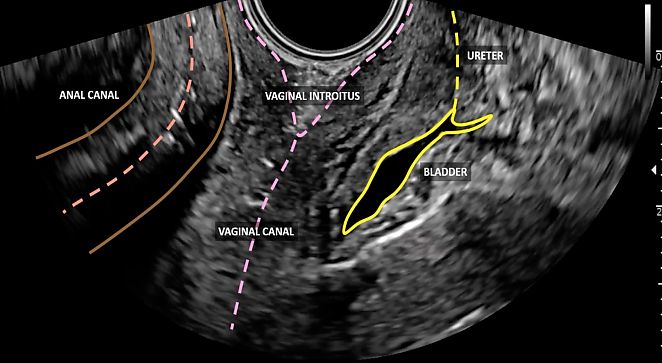

During this initial phase, the anorectal canal, the rectovaginal septum, the urethra and the vesicovaginal septum are also visualized (Figure 1). The vesicovaginal septum can be evaluated in a midsagittal section by pressing the uterus and vagina against the bladder (Video 1). Similarly, the rectovaginal septum can be assessed in a midsagittal section by pressing the probe against the rectum and vagina (Video 2). These movements allow the assessment of tissue elasticity and mobility in relation to surrounding tissues and organs, which is important to evaluate in the context of both benign (e.g. endometriosis) and malignant (e.g. neoplastic infiltration from cervical cancer) gynecological conditions.6

1

Visualization of pelvic structures from the vaginal introitus.

1

Vesicovaginal and vesicouterine septum.

2

Rectovaginal septum.

Bladder

To examine the bladder, the probe should be moved from right to left, scanning both the wall and the mucosa. The mucosa should be smooth, although occasionally irregular contours may be observed when the bladder is not fully distended. During evaluation of the bladder, endoluminal formations such as bladder neoplasms or calculi can be identified, as well as formations that invade the bladder from the outside (e.g. endometriotic nodules or invasive tumors).

The bladder wall is usually homogeneous with a thickness of less than 5 mm. A thickness exceeding 5 mm may be observed in cases of lower urinary tract symptoms such as chronic cystitis.7

Cervix and uterus

Examination of the uterus and cervix should be performed using two essential movements: a laterolateral movement along the longitudinal axis, and, after rotating the probe 90°, craniocaudal scrolling along the transverse axis.

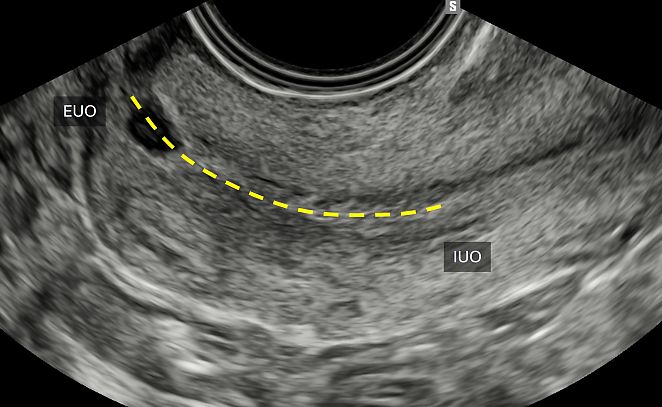

The cervix is a cylindrical organ that protrudes into the vagina and is bounded caudally by the external os or external uterine orifice (EUO) and cranially by the internal os or internal uterine orifice (IUO), which marks the junction between the cervix and the uterine body.8

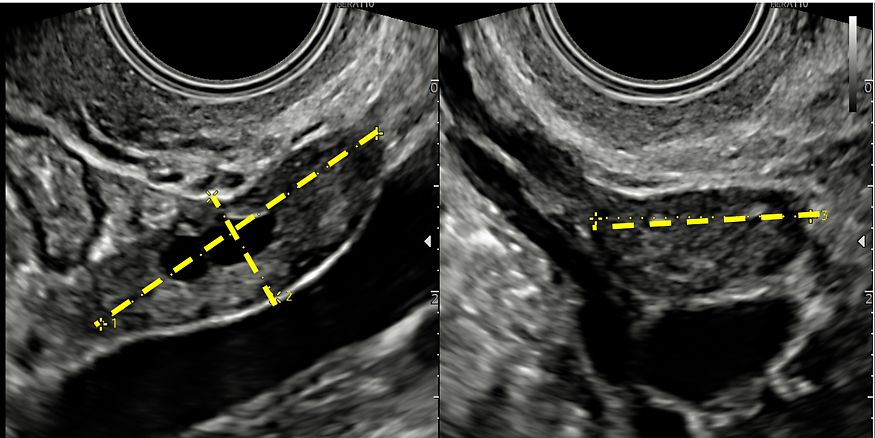

Through endocavitary ultrasound, either transvaginal or transrectal, the posterior and anterior lips of the cervix and its length can be evaluated, and measurements can be taken from the IUO to the EUO in a longitudinal plane (Figure 2). By examining the cervix in two orthogonal planes, cervical pathology – both benign (e.g. polyps, fibroids) and malignant – can be identified, by focusing on stromal infiltration, vascularization and assessment of tissue elasticity and mobility.

2

Longitudinal scan of the cervix, showing measurement of its length, which is the distance between the external uterine orifice (EUO) and the internal uterine orifice (IUO).

Ultrasound examination of the uterus includes evaluation of its orientation, dimensions (Figure 3), contours and morphology in order to exclude uterine malformations and to detect changes in echostructure of the myometrium due to the presence of benign (e.g. fibroids, adenomyosis) or malignant (e.g. sarcomas) pathology (Video 3). Orientation of the uterus is described in terms of both its version and flexion, where version indicates the relationship between the uterine body and the vagina, and flexion refers to the relationship between the uterine body and the cervix.

|

|

3

(a) Longitudinal scan of the uterus with measurements of its anteroposterior and craniocaudal diameters. (b) Transverse scan of the uterus with measurement of its laterolateral diameter.

3

Evaluation of the uterus.

It is important to evaluate the mobility of the uterus with respect to surrounding structures. The normal sliding motion of the uterus, referred to as a ‘positive sliding sign’, can be assessed by gently pressing the probe against the uterus in the anterior (Video 4) and posterior vaginal fornices. The lack of mobility is considered a ‘negative sliding sign’ and is associated with varying degrees of obliteration of the vesicouterine and/or rectovaginal septum, which may indicate, for example, the presence of deep endometriosis or malignancy.9

4

Anterior evaluation of the uterine sliding sign.

Endometrium

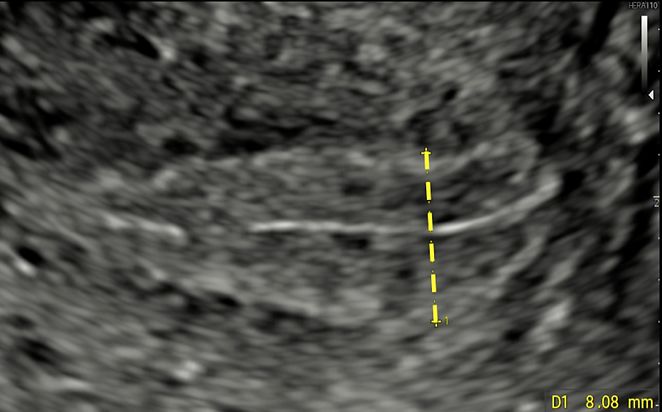

In a longitudinal plane of the uterus, the endometrium should be measured at its thickest point, including both endometrial layers. The measurement should be taken perpendicular to the midline, which corresponds to the line of junction between the two endometrial surfaces (Figure 4).

4

Longitudinal view of the uterus, showing measurement of the endometrium at its thickness point, perpendicular to the midline.

If fluid is present within the endometrial cavity, the thickness of each individual layer should be measured separately, and the two measurements should then be summed.

Based on the International Endometrial Tumor Analysis (IETA) consensus,10 qualitative assessment of endometrial morphology should include evaluation of echogenicity, description of the midline and endometrial–myometrial junction, and, if appropriate, a color/power Doppler examination.

Echogenicity of the endometrium is described as hyperechoic, isoechoic or hypoechoic in comparison to the echogenicity of the myometrium. Endometrial echogenicity is classified as ‘uniform’, when homogeneous and concordant with the menstrual cycle, or ‘non-uniform’, when heterogeneous, asymmetric or cystic.

The endometrial midline is defined as ‘linear’ if a straight, hyperechoic interface is seen within the endometrium, ‘non-linear’ if it is a wavy, hyperechoic interface, and ‘irregular’ or ‘undefined’ in the absence of a clearly evaluable interface.

The endometrium–myometrium junction should be described as ‘regular’, ‘irregular’, ‘interrupted’ or ‘undefined’.

The color/power Doppler examination allows evaluation of the grade of vascularization, subjectively scored from 1 to 4, with 1 indicating no vascularization and 4 indicating rich vascularization, and, if present, assessment of the vascular pattern.

These parameters provide a comprehensive description of the endometrium, enabling the detection of endocavitary benign lesions (e.g. polyps, fibroids) when regular margins and vascularization are present, or helping to address suspicion of malignancy in cases of irregular margins, a multifocal vascular pattern, or myometrial infiltration.10 More detailed information about assessment of the endometrium is provided in another chapter in this volume (Endometrial Pathology | Article | GLOWM).

Adnexa

The ovaries are typically positioned near the lateral pelvic wall within the ovarian fossae, which are triangular spaces on the posterior side of the broad ligament. These spaces are bordered superiorly by the external iliac vessels, ventrally by the broad ligament of the uterus and posteriorly by the ureter and internal iliac vessels.11 However, their position can vary from patient to patient due to several factors, such as previous surgery or endometriosis. In such cases, the ovaries may be positioned more cranially, above the uterine fundus, or located in a retrouterine position within the pouch of Douglas This can occur when the uterus is laterally deviated, meaning it is positioned abnormally, tilted laterally from its usual anatomical position.

There are different techniques for identifying the ovaries; each of these should be repeated on both sides until adequate visualization of both adnexa is achieved.

After identifying the uterine fundus in a transverse scan, the utero-ovarian ligament should be followed laterally to reach the ovarian fossa (Video 5). Sometimes, slight abdominal pressure can be helpful to move the intestines and reveal the ovary. By rotating the probe, both external and internal iliac vessels can be identified. If the ovary is not visible using the transvaginal approach, the transabdominal approach should be considered for possible cranial localization of the adnexa.

5

Evaluation of the (left) ovary.

Once identified, laterolateral and craniocaudal scrolling maneuvers should be performed to evaluate the presence of any pathological formations and to assess the ovary’s mobility in relation to the surrounding structures. In particular, the mobility of the ovary should be assessed with respect to the pelvic wall, the uterine structure, and the surrounding intestinal loops. Once the ovary has been fully examined, it should be visualized and imaged in two orthogonal planes and the appropriate measurements should be taken (Figure 5). It is important to remember that the adnexal region also includes the Fallopian tubes, which are usually not visible unless there is free fluid in the pelvis or the tubes are dilated (e.g. in cases of hydrosalpinx).

5

Assessment of the (left) adnexa with measurements taken in the three orthogonal planes.

Parametrium

The parametrium consists of the structures surrounding the cervix and vagina, including septa, ligaments and lymphovascular tissue, extending from the parietal and visceral pelvic fascia to the lateral pelvic wall ventrally, laterally and dorsally.12

Sonographic assessment of these anatomical structures plays a crucial role in detecting local spread of disease in gynecological malignancies (e.g. cervical cancer). By providing essential diagnostic information, ultrasound aids clinicians in treatment planning and decision-making. Additionally, parametrial imaging is valuable in assessing benign gynecological conditions, particularly deep endometriosis, for which precise evaluation is crucial for accurate diagnosis and effective management.13

To assess the parametrium, no patient preparation is required, except for a minimal amount of fluid in the bladder. Typically, the transvaginal probe is positioned in the anterior or in the posterior vaginal fornix in cases of anteverted or retroverted uterus, respectively.

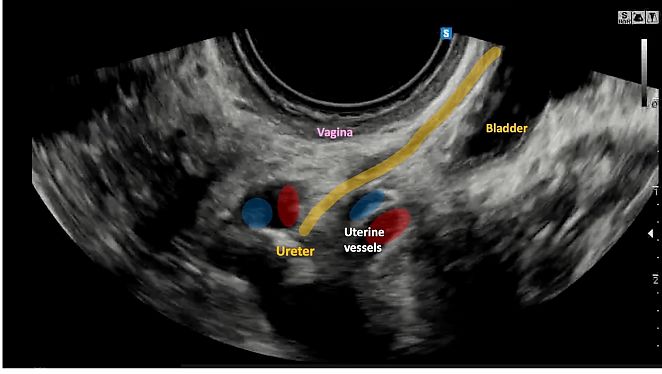

Anterior parametrium

The anterior parametrium is defined as the space bounded anteriorly by the bladder and laterally by the terminal part of the ureters (i.e. the section between the crossing point with the uterine artery and the bladder inlet) (Figure 6).13

6

Longitudinal view of the anterior parametrium.

The cranial portion of the anterior parametrium surrounding the cervix is bounded medially by the vesicouterine septum and laterally by the vesicouterine ligaments. The vesicouterine septum is a potential space located between the bladder and the uterus, created by the reflection of the peritoneum at the vesicouterine fold (Video 6). The vesicouterine ligaments, composed of connective tissue, laterally define the boundaries of the vesicouterine septum.14

6

Evaluation of the vesicouterine septum.

The caudal part of the anterior parametrium surrounding the vagina consists of the vesicovaginal ligaments, which are in continuum with their cranial counterparts.13 During ultrasound examination, the anterior parametrium can be assessed by placing the probe in the anterior vaginal fornix to visualize the uterine cervix, bladder and urethra in the midsagittal plane. Then, by moving the probe laterally from each corner of the bladder trigone to both sides of the pelvis, the distal tracts of the right and left ureters can be visualized by slightly rotating the probe clockwise or counterclockwise, respectively. On ultrasound, the ureters appear as tubular hypoechoic conduits exhibiting peristalsis (Video 7). They can be traced from each lateral corner of the bladder trigone, crossing the bladder wall tangentially towards the lateral pelvic wall. The distal extravesical segment of the ureter is delineated by hyperechogenic structures: by the vesicouterine ligaments (cranially) and the vesicovaginal ligaments (caudally) (Video 8). The vesicovaginal septum and its integrity can also be assessed during transvaginal ultrasound by gently pressing the uterus against the bladder in a midsagittal section. Normal sliding motion indicates the absence of infiltration within the septum.

7

Distal ureteral tract.

8

Evaluation of distal ureteral tract with the vesicovaginal and vesicouterine ligaments.

Lateral parametrium

The lateral parametrium (or paracervix, or paracolpium), corresponds to the area located between the cervix and the lateral pelvic wall.13 This region contains lymphovascular structures (i.e. uterine artery, superficial uterine vein, umbilical artery, external iliac vessels) and is divided into medial and lateral parts by the ureter, which is located centrally within this area.13

During ultrasound examination, the lateral parametrium can be assessed by placing the probe in the posterior vaginal fornix to visualize the midsagittal plane of the uterus. The probe can then be moved laterally towards the pelvic sidewall until the iliac vessels are visualized, providing a longitudinal view of the ureter and uterine artery. By rotating the probe 90°, with a transverse section of the ureter visualized in the middle, the medial extension of the lateral parametrium (i.e. from the cervix to the ureter) and a lateral extension of the lateral parametrium (i.e. from the ureter to the iliac vessels/pelvic wall) can be studied (Video 9).

9

Evaluation of the lateral parametrium.

Posterior parametrium

The posterior parametrium includes various components located at different craniocaudal levels (i.e. uterosacral ligament, rectovaginal ligament and lateral rectal ligament).15 The cranial portion of the posterior parametrium surrounding the cervix comprises the uterosacral (or sacrouterine) ligaments, which represent a common site of infiltration in patients with deep endometriosis.16 The uterosacral ligaments are supportive structures that originate from the torus (i.e. the point on the posterior cervical profile corresponding to the internal uterine ostium) and extend posteriorly to the sacrum.13 The caudal part of the posterior parametrium surrounding the vagina consists of the rectovaginal septum and the rectovaginal ligaments. The rectovaginal septum is a fibromuscular layer located between the posterior wall of the vagina and the anterior wall of the rectum13 (Video 10). Rectovaginal ligaments laterally define the rectovaginal septum and are in continuum with the uterosacral ligaments, extending from the posterior vaginal wall to the anterior wall of the rectum.

10

Evaluation of rectovaginal septum.

Finally, below the rectovaginal ligaments and in continuum with them are the lateral rectal ligaments.

On ultrasound examination, the uterosacral and rectovaginal ligaments can be evaluated in both longitudinal and transverse planes, starting by placing the probe in the posterior vaginal fornix to visualize the cervical canal and retrocervix (i.e. the external profile of the cervical canal, located between the torus and the posterior vaginal fornix). They can be identified in the midsagittal plane by gently pressing the probe laterally with respect to the cervix (Video 11) while maintaining the longitudinal section.17 Alternatively, they can be identified by rotating the probe 90° at the level of the uterine torus and by scrolling the probe caudally up to the level of the posterior vaginal fornix (Video 12).18 Additionally, by moving the probe laterally and angling it at 45°, these ligaments can be visualized along their entire lateral extension.

11

Evaluation of the uterosacral ligaments in a longitudinal section.

12

Evaluation of the uterosacral ligaments in a transverse section.

On ultrasound, these ligaments typically appear as thin, hyperechogenic tissue surrounding the cervix and vagina (Video 13). In cases of endometriosis, the uterosacral ligaments may appear thickened or interrupted by hypoechoic nodules while, in locally advanced cervical cancer, they may be infiltrated by neoplastic tissue.

13

Uterosacral ligaments.

The rectovaginal septum and its integrity can also be assessed during transvaginal ultrasound by gently pushing the probe against the rectum and vagina. Normal sliding motion indicates the absence of infiltration within the septum.

Vesicouterine pouch and pouch of Douglas

The vesicouterine pouch is an extension of the peritoneal cavity located between the bladder and the anterior wall of the uterus. It can be easily identified, particularly when a small amount of fluid collects within it (Figure 7).

7

Vesicouterine pouch.

The pouch of Douglas (or rectouterine pouch) is the extension of the peritoneal cavity between the rectum and the posterior wall of the uterus. It is the deepest point of the abdominopelvic cavity and, as such, a site at which fluids and exudates are likely to accumulate.

The fluid level in the pelvis can be assessed with a single vertical measurement relative to the screen (Figure 8). The fluid may appear clear, or ‘anechoic,’ or may exhibit ‘low-level’ echogenicity. The amount of fluid can fluctuate throughout the menstrual cycle.

8

Measurement of fluid (dashed line) within the pouch of Douglas, showing a relatively small volume.

The peritoneum covering both the vesicouterine pouch and the pouch of Douglas can be a common site for superficial endometriosis, and it can also be affected by carcinomatotic nodules in the case of gynecological malignancy, such as ovarian or endometrial cancer.19

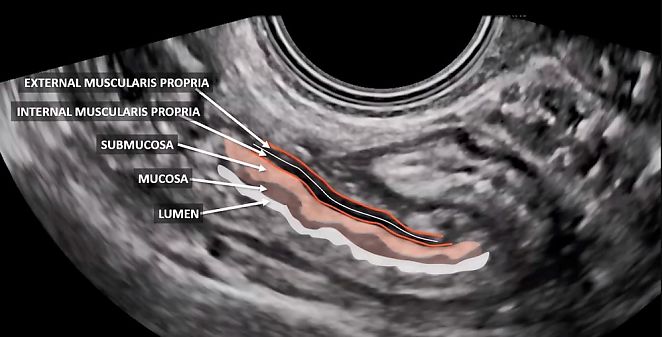

Rectum

The rectum can be evaluated during a transvaginal gynecological pelvic ultrasound, allowing for the identification of the different layers of its wall (Figure 9). Although this assessment is not a routine part of standard gynecological ultrasound, it is essential for patients with endometriosis or oncological pathology. In such cases, it enables the precise determination of the lesion's location and grade of infiltration.

9

Longitudinal section of rectum, showing its layers.

Retroperitoneum

Knowing how to examine the retroperitoneum is essential for distinguishing whether a mass is intraperitoneal or extraperitoneal (e.g. lymph nodes or lymphoceles). A key aspect of ultrasound assessment is dynamic evaluation, performed by applying gentle pressure with the endocavitary probe while simultaneously pressing on the lower abdomen with the free hand. This technique enables the assessment of structural mobility, facilitating the differentiation between intraperitoneal and retroperitoneal structures.20 Indeed, intraperitoneal organs typically exhibit a sliding movement when pressure is applied with the probe, whereas retroperitoneal structures remain more fixed, demonstrating minimal or no movement in most cases.21

There has been increasing interest in the deepest layer of the pelvic sidewall. This layer encompasses crucial pelvic muscles, such as the obturator internus and piriformis, which are positioned near the pelvic bones i.e. the ala of the sacrum and the ischial spine, respectively.20,22 Interwoven between these muscles are the branches of the sacral plexus. This anatomical region can be effectively evaluated through transvaginal or transrectal examination,22 offering valuable insight into its structure and function. A systematic approach to evaluate the pelvic sidewall using ultrasound has been recently proposed by Fischerova et al.20 Assessing the anatomical structures – including muscles, vessels, lymph nodes, nerves and ureters – is crucial for detecting both local spread of disease in gynecological malignancies and benign conditions such as endometriosis, providing critical information to guide clinical decision-making.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- Adopt a systematic approach: following a standardized scanning protocol helps ensure a thorough and comprehensive evaluation of all pelvic organs.

- Perform endocavitary ultrasound examination: whenever possible, an endocavitary approach (either transvaginal or transrectal) is preferred, as it provides the most detailed assessment of pelvic organs. However, a transabdominal scan remains a valuable alternative when necessary, and is essential for evaluating structures extending beyond the pelvis.

- Multiple plane and dynamic evaluation: all pelvic organs should be examined across multiple planes, assessing their volume and contours.

- Dynamic evaluation: applying gentle pressure to the probe aids in assessing tissue and organ elasticity, mobility and tenderness. This dynamic approach enhances diagnostic accuracy and helps evaluate relationships with surrounding structures, particularly in conditions such as endometriosis and malignant pathology.

- Importance of vascularity assessment: color Doppler examination plays a crucial role in differentiating between benign and malignant lesions by evaluating vascular patterns and blood flow characteristics.

- Beyond the ovaries and uterus: numerous pelvic structures can be evaluated through ultrasound examination, providing valuable diagnostic insights.

- Parametrial evaluation: the parametrium consists of the structures surrounding the cervix and vagina, extending from the parietal and visceral pelvic fascia to the lateral pelvic wall ventrally, laterally and dorsally. Parametrial assessment is particularly important in conditions such as endometriosis and malignant pathology, including cervical cancer. No specific patient preparation is required for this evaluation.

- Rectal evaluation: although rectal assessment is not routinely included in standard gynecological ultrasound, it is essential for patients with endometriosis or oncological pathology. Ultrasound allows for the identification of the different layers of the rectal wall, providing valuable diagnostic information.

- Retroperitoneal evaluation: recognizing whether a mass is intraperitoneal or extraperitoneal is crucial for patient management. Ultrasound examination also enables a deep, systematic assessment of the pelvic sidewalls, muscles, vessels and lymph nodes, providing valuable diagnostic insights.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) of this chapter declare that they have no interests that conflict with the contents of the chapter.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

REFERENCES

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin. Management of adnexal masses. Obstet Gynecol. 2007 Jul;110(1):201–214. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000263913.92942.40. PMID: 17601923. | |

Benacerraf BR, Abuhamad AZ, Bromley B, Goldstein SR, Groszmann Y, Shipp TD, Timor-Tritsch IE. Consider ultrasound first for imaging the female pelvis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Apr;212(4):450–455. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.02.015. PMID: 25841638. | |

Timor-Tritsch IE, Monteagudo A, Rebarber A, Goldstein SR, Tsymbal T. Transrectal scanning: an alternative when transvaginal scanning is not feasible. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2003 May;21(5):473–479. doi: 10.1002/uog.110. PMID: 12768560. doi: | |

Scanlan KA, Propeck PA, Lee FT Jr. Invasive procedures in the female pelvis: value of transabdominal, endovaginal, and endorectal US guidance. Radiographics. 2001 Mar–Apr;21(2):491–506. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.21.2.g01mr21491. PMID: 11259711. | |

Karena ZV, Mehta AD. Sonography Female Pelvic Pathology Assessment, Protocols, and Interpretation. [Updated 2023 Aug 14]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan–. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK585034/ | |

Fischerova D, Frühauf F, Burgetova A, Haldorsen IS, Gatti E, Cibula D. The Role of Imaging in Cervical Cancer Staging: ESGO/ESTRO/ESP Guidelines (Update 2023). Cancers (Basel). 2024 Feb 14;16(4):775. doi: 10.3390/cancers16040775. PMID: 38398166; PMCID: PMC10886638. | |

Oelke M, Khullar V, Wijkstra H. Review on ultrasound measurement of bladder or detrusor wall thickness in women: techniques, diagnostic utility, and use in clinical trials. World J Urol. 2013 Oct;31(5):1093–1104. doi: 10.1007/s00345-013-1030-6. Epub 2013 Feb 6. PMID: 23386057. | |

Wildenberg JC, Yam BL, Langer JE, Jones LP. US of the Nongravid Cervix with Multimodality Imaging Correlation: Normal Appearance, Pathologic Conditions, and Diagnostic Pitfalls. Radiographics. 2016 Mar–Apr;36(2):596–617. doi: 10.1148/rg.2016150155. PMID: 26963464. | |

Alcázar JL, Eguez PM, Forcada P, Ternero E, Martínez C, Pascual MÁ, Guerriero S. Diagnostic accuracy of sliding sign for detecting pouch of Douglas obliteration and bowel involvement in women with suspected endometriosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2022 Oct;60(4):477–486. doi: 10.1002/uog.24900. Epub 2022 Sep 12. PMID: 35289968; PMCID: PMC9825886. | |

Leone FP, Timmerman D, Bourne T, Valentin L, Epstein E, Goldstein SR, Marret H, Parsons AK, Gull B, Istre O, Sepulveda W, Ferrazzi E, Van den Bosch T. Terms, definitions and measurements to describe the sonographic features of the endometrium and intrauterine lesions: a consensus opinion from the International Endometrial Tumor Analysis (IETA) group. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Jan;35(1):103–112. doi: 10.1002/uog.7487. PMID: 20014360. | |

Mihu D, Mihu CM. Ultrasonography of the uterus and ovaries. Med Ultrason. 2011 Sep;13(3):249–252. PMID: 21894299. | |

Querleu D, Bizzarri N, Fanfani F, Fagotti A, Scambia G. Simplified anatomical nomenclature of lateral female pelvic spaces. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2022;32:1183–1188. https://doi.org/10.1136/ijgc-2022-003531 | |

Moro F, Zermano S, Ianieri MM, De Cicco Nardone A, Carfagna P, Ciccarone F, Ercoli A, Querleu D, Scambia G, Testa AC. Dynamic transvaginal ultrasound examination for assessing anatomy of parametrium. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2023 Dec;62(6):904–906. doi: 10.1002/uog.26313. PMID: 37470676. | |

Ercoli A, Delmas V, Fanfani F, Gadonneix P, Ceccaroni M, Fagotti A, Mancuso S, Scambia G. Terminologia Anatomica versus unofficial descriptions and nomenclature of the fasciae and ligaments of the female pelvis: a dissection-based comparative study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Oct;193(4):1565–1573. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.05.007. PMID: 16202758. | |

Ceccaroni M, Clarizia R, Roviglione G, Ruffo G. Neuro-anatomy of the posterior parametrium and surgical considerations for a nerve-sparing approach in radical pelvic surgery. Surg Endosc. 2013 Nov;27(11):4386–4394. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3043-z. Epub 2013 Jun 20. PMID: 23783554. | |

Scioscia M, Scardapane A, Virgilio BA, Libera M, Lorusso F, Noventa M. Ultrasound of the Uterosacral Ligament, Parametrium, and Paracervix: Disagreement in Terminology between Imaging Anatomy and Modern Gynecologic Surgery. J Clin Med. 2021 Jan 23;10(3):437. doi: 10.3390/jcm10030437. PMID: 33498777; PMCID: PMC7865545. | |

Leonardi M, Martins WP, Espada M, Arianayagam M, Condous G. Proposed technique to visualize and classify uterosacral ligament deep endometriosis with and without infiltration into parametrium or torus uterinus. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jan;55(1):137–139. doi: 10.1002/uog.20300. PMID: 31008537. | |

Savelli L, Ambrosio M, Salucci P, Raimondo D, Arena A, Seracchioli R. Transvaginal ultrasound features of normal uterosacral ligaments. Fertil Steril. 2021 Jul;116(1):275–277. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.11.019. Epub 2021 Feb 12. PMID: 33583595. | |

Reid S, Lu C, Casikar I, Reid G, Abbott J, Cario G, Chou D, Kowalski D, Cooper M, Condous G. Prediction of pouch of Douglas obliteration in women with suspected endometriosis using a new real-time dynamic transvaginal ultrasound technique: the sliding sign. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Jun;41(6):685–691. doi: 10.1002/uog.12305. PMID: 23001892. | |

Fischerova D, Culcasi C, Gatti E, Ng Z, Burgetova A, Szabó G. Ultrasound assessment of the pelvic sidewall: methodological consensus opinion. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2025 Jan;65(1):94–105. doi: 10.1002/uog.29122. Epub 2024 Nov 5. PMID: 39499650; PMCID: PMC11693842. | |

Timor-Tritsch IE. Sliding organs sign in gynecological ultrasound. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Jul;46(1):125–126. doi: 10.1002/uog.14901. Epub 2015 Jun 2. PMID: 25975534. | |

Szabó G, Madár I, Hudelist G, Arányi Z, Turtóczki K, Rigó J Jr, Ács N, Lipták L, Fancsovits V, Bokor A. Visualization of sacral nerve roots and sacral plexus on gynecological transvaginal ultrasound: feasibility study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2023 Aug;62(2):290–299. doi: 10.1002/uog.26204. PMID: 36938682. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards program CLICK HERE)

%5D.jpg?1627993)

%5D.jpg?1628013)