This chapter should be cited as follows:

Fragomeni SM, Garganese G, Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.421903

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Gynecology Module

Volume 10

Ultrasound in gynecology

Volume Editors:

Professor Antonia Testa, Agostino Gemelli University Hospital, Rome, Italy

Professor Simona Maria Fragomeni, Agostino Gemelli University Hospital, Rome, Italy

Chapter

Ultrasound Evaluation of Inguinal and Pelvic Lymph Nodes

First published: June 2025

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

Lymph node metastases are a common feature associated with many gynecological malignancies. Among the lymphatic stations, the inguinal lymph nodes are particularly well-suited to evaluation by ultrasound. These nodes are most frequently affected by metastases from vulvar carcinomas, which usually first involves the inguinal lymph nodes before progressing to the pelvic nodes. Pelvic lymph nodes, which include the external, internal and common iliac groups, serve as major drainage basins for tumors arising from various pelvic organs such as the uterus, cervix, ovary, vagina and vulva.1 In cervical and endometrial cancers, pelvic lymph nodes, particularly the external and obturator chains, are typically the first sites of lymphatic spread, preceding para-aortic involvement. Ovarian cancer, on the other hand, can bypass the pelvic nodes entirely, spreading directly to the para-aortic lymph nodes.

In this chapter, we describe the sonographic assessment of inguinal and pelvic lymph nodes focusing on their anatomical landmarks, scanning techniques, and key sonographic features relevant for clinical staging and management.

INGUINAL LYMPH NODES

Contribution of ultrasound

The inguinofemoral lymph nodes are typically the first nodal station involved in vulvar cancer, and accurate surgical staging of this region is crucial in assessing early-stage disease. Vulvar cancer is the fourth most common gynecologic malignancy, with an incidence of 1–3 per 100 000 women.1,2,3,4,5 The spread of vulvar squamous cell carcinoma can occur through three primary routes: direct extension, lymphatic dissemination and hematogenous spread.6

The standard treatment for early-stage vulvar cancer includes radical local excision of the tumor combined with either sentinel lymph node biopsy and/or inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy, based on preoperative lymph node assessment and local tumor spread.7,8,9,10,11 Therefore, a precise preoperative lymph node evaluation is essential to tailor surgery appropriately, avoid unnecessary procedures and potential complications, and plan the most suitable treatment strategy.11

Current international guidelines (ESGO, NCCN) include ultrasound and fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography/computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT) among the recommended techniques for assessing inguinal lymph nodes.7,8,12,13,14,15,16 Ultrasound has demonstrated high accuracy in detecting nodal metastases when performed by an experienced operator.17

In the preoperative evaluation of patients with vulvar carcinoma, multiple clinical and ultrasound features can be assessed during the outpatient visit to predict inguinal nodal status. Certain features may be more indicative of metastatic involvement and can guide targeted, ultrasound-guided invasive diagnostic assessment (e.g. cytology or histology), which can then help define the appropriate surgical approach (e.g. sentinel node biopsy or lymphadenectomy).18,19

Ultrasound is widely available, safe, and relatively cost-effective, making it a potential method of choice for detecting inguinal nodal metastases. Until 2021, there were no international recommendations or standardized reference indications for ultrasound assessment of inguinal lymph nodes in vulvar cancer. The Vulvar International Tumor Analysis (VITA) group was established in 2016 during the 26th World Congress on Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology, with the goal of providing such standardized guidance on examination technique, measurements and terminology to be used when describing the ultrasound assessment.20

Ultrasound approach

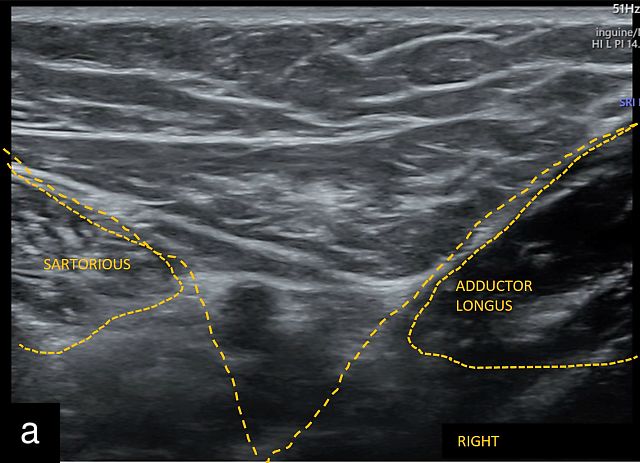

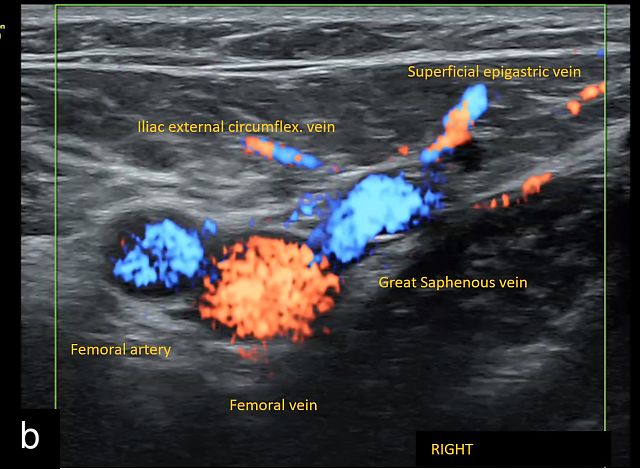

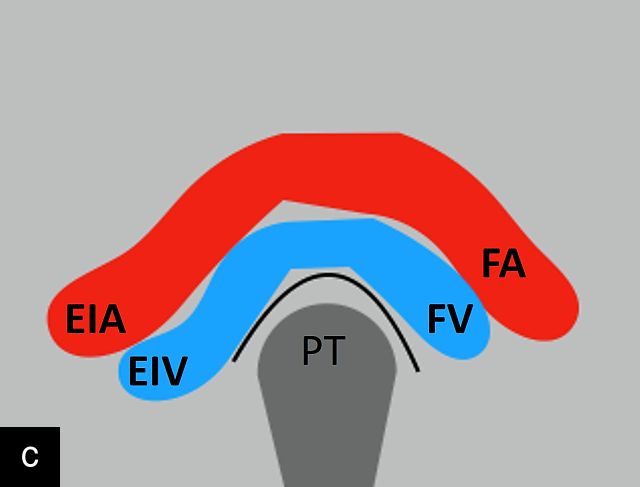

Inguinal lymph nodes should be evaluated using a high-frequency linear probe (7.5–14 MHz). To examine thoroughly the inguinal region, the following anatomical landmarks should be identified:

- the apex of the femoral triangle, located at the intersection of the sartorius and adductor longus muscles (‘V sign’) (Figure 1a)

- the saphenofemoral junction, visible in transverse section with the tributary veins of the great saphenous vein (‘snail sign’) (Figure 1b)

- the inguinal ligament, seen as a hyperechoic structure between the anterior superior iliac spine and the pubic tubercle; in longitudinal scan, the curvature of the femoral vessels forming the external iliac vessels represents the ‘hill sign’ (Figure 1c).

Once these landmarks have been identified correctly, the superficial fascia (Camper’s fascia) can be visualized, beneath which the superficial lymph nodes are located. Deep lymph nodes are assessed by identifying the saphenofemoral junction and the medial area adjacent to it.

|  |  |

1

Anatomical landmarks for location of the inguinal lymph nodes on ultrasound. (a) Valley or V sign. (b) Snail sign. (c) Hill sign. EIA, external iliac artery; EIV, external iliac vein; FA, femoral artery; FV, femoral vein; PT, pubic tubercle

Inguinal lymph nodes are the first site of metastasis in vulvar cancer, and their suspicious location can be described using the five zones (levels) around the junction of the great saphenous vein with the femoral vein, as described by Daseler et al.21 (Figure 2): Level I (superomedial): around the superficial epigastric and external pudendal veins; Level II (superolateral): around the superficial circumflex iliac vein; Level III (inferolateral): around the lateral accessory saphenous vein; Level IV (inferomedial): medial to the great saphenous vein; Level V (central): around the saphenofemoral junction.

Each lymph node should be examined with sufficient magnification to evaluate perinodal tissues and describe nodal features based on the VITA criteria.

2

Diagrammatic representation of right groin, showing Daseler levels (I–V) used to classify site of inguinal lymph nodes. Orange circle denotes the saphenofemoral junction.

Ultrasound description

Using VITA terminology, lymph nodes should be described according to their dimensional, morphological and vascular criteria.

Dimensional criteria

Short- and long-axis measurements should be taken, and the absolute values and the ratio between them should be calculated. A long-to-short axis ratio <2 suggests a round shape, often associated with metastatic nodes. Cortical and medullary thickness should also be measured in the scan at the point at which the cortex appears thickest. A cortical-to-medullary ratio >1 indicates cortical thickening.

Morphological criteria

Morphological criteria consist of eight categories, as follows:

- Shape: described as regular (oval/elliptical or round) or irregular (lobulated or with spicules on the outer margin) (Figure 3).

- Nodal-core sign: defined by the visibility of both the hilum and medulla. Absence may indicate metastatic replacement, though partial presence may still occur (Figure 4).

- Cortical thickening (only if medulla is visible): defined as focal (<50% of nodal circumference) or diffuse (>50% of nodal circumference, further categorized as concentric or eccentric) (Figure 5).

- Echogenicity: normal nodes are homogeneous. Abnormal nodes may show focal (hyperechoic deposits, cystic areas) or diffuse (e.g. ‘sand pattern’ or reticulation) heterogeneity. Cystic changes are often associated with metastases (Figure 6).

- Capsular interruption: a break in the hyperechoic capsule suggests extracapsular tumor spread (Figure 7).

- Corticomedullary interface distortion: irregularity in the normally clear boundary between cortex and medulla (Figure 8).

- Perinodal hyperechogenic ring: a bright rim around the node, not limited to the posterior region, indicative of a desmoplastic reaction (Figure 9).

- Grouping: positioning of nodes unusually close together, further defined as 'partial', when the nodes remain distinct, or 'complete' when they fuse, such that individual boundaries become indistinguishable (Figure 10).

3

Classification of lymph node shape as regular (a) or irregular (b).

4

Absent nodal core sign, in this case indicating replacement of lymph node hilum and medulla by metastasis.

5

Lymph node cortical thickening, defined as focal (a) or diffuse (b).

6

Abnormal lymph node echogenicity, defined as focal with hyperechoic deposits (a) or cystic areas (b), or diffuse with sand pattern (c) or reticulation (d).

7

Interruption of hyperechoic lymph node capsule (arrows).

8

Distortion of the lymph node corticomedullary interface (arrows).

9

Perinodal hyperechogenic ring around the lymph node (dashed circle).

10

Grouping of lymph nodes, which can be partial (a) or complete (b).

Vascular criteria

Using Doppler (color or power), with pulse repetition frequency (PRF) set at 0.3–0.6 kHz and with minimal probe pressure, the vascularization score (1–4) is assigned as per IOTA guidelines.22 Blood vessel architecture is described as: hilar (central, parallel to long axis) (Figure 11a), transcapsular (vessels penetrating from the outside) (Figure 11b) or combined (both patterns).

11

Lymph node blood-vessel architecture, showing hilar (a) and transcapsular (b) patterns.

Final classification

A subjective assessment, based on the combined evaluation of dimensional, morphological and vascular characteristics, allows the operator to classify each lymph node from LN1 (normal) to LN5 (metastatic) (Figure 12).

12

Five categories (LN1–LN5) of lymph node classification by subjective assessment.

Examples of lymph node categories, characterized by their ultrasound features and the associated subjective evaluation, are presented below.

Normal. Oval shape, visible nodal-core sign, thin homogeneous cortex, hilar flow (LN1).

Reactive. Oval shape, visible nodal-core sign, concentrically thickened cortex due to immune response (LN2). Some may lack medulla/hilum (LN3).

Post-reactive. Large hyperechoic medulla, thin cortex, sometimes a ‘sandwich’ pattern (LN1).

Metastatic. Eccentric cortical thickening displacing hilum/medulla, non-homogeneous cortex (e.g. cystic areas), hypoechoic echogenicity relative to surrounding tissue, capsular interruption, or transcapsular vascular architecture. Fully infiltrated nodes are round and lack hilum/medulla (LN4–5).

The use of standardized terms and definitions has been critical in developing and validating malignancy prediction models for ovarian and uterine tumors, as demonstrated by the IOTA, IETA and MUSA groups.22,23,24 Similarly, the VITA group has established techniques and terminology that can be applied routinely for describing inguinal lymph nodes in vulvar cancer patients, both for clinical staging and as a foundation for future prospective studies (Table 1).20

1

Inguinal ultrasound structured report for lymph node assessment according to VITA criteria.20

Daseler level | 1–5 |

Subjective assessment | LN1–LN5 |

Size | Long axis, short axis, L/S ratio – cortex, medulla, C/M ratio |

Shape | Regular (oval, round)/irregular (lobulated/spiculated) |

Nodal-core sign | Present/absent |

Cortical thickening | Absent/focal/concentric uniform/concentric non-uniform/eccentric uniform/eccentric non-uniform/not assessable |

Echogenicity | Homogeneous/non-homogeneous: focal heterogeneity (cysts, hyperechoic deposits) or diffuse heterogeneity (sand pattern, reticulation)/indeterminate |

Perinodal hyperechogenic ring | Present/absent |

Corticomedullary interface distortion | Present/absent (not assessable if medulla not visible) |

Capsular interruption | Present/absent |

Grouping | Present (partial/complete)/absent |

Vascular architecture | Hilar/transcapsular/combined |

Color score | 1–4 |

PELVIC PARIETAL LYMPH NODES

Contribution of ultrasound

Pelvic lymph nodes are typically the first sites of lymphatic spread in endometrial and cervical cancers, which, along with ovarian cancer, are the most commonly encountered gynecological cancers.1 Functionally, pelvic lymph nodes drain lymph from the pelvic organs and also receive lymphatic flow from the inguinal region and lower limbs. Due to the continuity of the lymphatic network, lymph from the pelvic nodes then progresses toward the abdominal lymphatic chains. Pelvic lymph nodes are divided into two main categories: parietal and visceral. Both parietal and visceral pelvic lymph nodes can be identified using imaging techniques typically employed to visualize the pelvic sidewall vasculature. Visceral nodes, such as the parauterine ones, are located near the internal iliac artery's visceral branches and are responsible for draining the pelvic organs. Parietal lymph nodes are found around the parietal branches of the internal iliac artery and along the external and common iliac vessels; this group includes the common, external and internal (hypogastric) iliac lymph nodes. Obturator lymph nodes, situated in the obturator fossa, are considered part of the external iliac group, whereas the sacral nodes are associated with the internal iliac group.25,26,27 Our focus henceforth will be on parietal nodes due to their key role in lymphatic drainage, accessibility, and relevance in cancer staging and treatment planning.

To ensure comprehensive assessment, a combination of transvaginal (or transrectal) endocavitary and transabdominal ultrasound is recommended. This dual method helps to avoid overlooking nodes that lie outside the field of view of a single approach. The VITA consensus provides a standardized nomenclature to aid in distinguishing between benign and malignant lymph node characteristics.20

Ultrasound approach

Ultrasound assessment of the parietal lymph nodes typically begins with a pelvic examination using a high-resolution endocavitary probe (transvaginal, or transrectal in the case of post-treatment stenosis or virgin patient), followed by a transabdominal scan to evaluate areas not accessible by the internal approach, especially anterior regions near the vascular lacuna.

The patient is placed in lithotomy position, and an empty bladder is preferred for optimal imaging. A systematic evaluation of the pelvic sidewall is recommended, particularly following the method described by Fischerova et al.,28 which allows a thorough assessment of the iliac vessels and detection of pathologically enlarged lymph nodes. The following steps, as well as the imaging techniques employed, closely follow the approach proposed by Fischerova, which provides a structured and reproducible method for evaluating pelvic lymph nodes.

Systematic assessment

Endocavitary ultrasound

The following steps should be taken with either a transvaginal or transrectal probe.

Step 1: identify the uterine vessels lateral to the cervix;

Step 2: locate the obturator artery, a branch of the anterior division of the internal iliac artery (this is a frequent site for pathological lymph nodes in gynecological malignancies);

Step 3: identify the posterior division of the internal iliac artery and its branches;

Step 4: follow both anterior and posterior branches up to the iliac bifurcation;

Step 5: continue along the external iliac artery up to the vascular lacuna, checking for nodes close to the inguinal canal (especially the medial node, also known as Cloquet’s node).

Transabdominal ultrasound

To complete the evaluation, a convex transducer should be used, starting at the inguinal ligament and tracking the femoral vessels as they become the external iliac vessels. Scanning in an oblique plane with medial and lateral sweeps is essential to avoid missing any lymph nodes. As the probe moves cranially, the following steps should be taken

Step 1: follow the common iliac vessels along the psoas major muscle;

Step 2: visualize the bifurcations of the inferior vena cava (IVC) and aorta at L5 and L4, respectively;

Step 3: assess the lumbar lymph nodes longitudinally and transversely along the aorta and IVC up to the diaphragm.

Each lymph node should be documented in both planes and described using the standardized VITA criteria.

Ultrasound description

The detailed application of VITA criteria would be desirable for the assessment of pelvic lymph nodes. However, due to their anatomical location and depth, some criteria may be difficult to apply. When performing an ultrasound assessment of pelvic lymph nodes, a standardized descriptive approach should be followed to ensure clarity and consistency in reporting. The key parameters include: location, size, shape, margins, internal structure and vascularization.29

Location

Common iliac nodes are located above the bifurcation of the iliac vessels. External iliac nodes are positioned along the external iliac vessels, including the obturator nodes in the obturator fossa. Internal iliac nodes are found near the internal iliac vessels, often close to the uterine artery and deep pelvic sidewall. Parauterine and paravaginal nodes are adjacent to the uterus and vaginal walls. Pararectal nodes are located along the rectum, following the middle rectal vessels.

Size and shape

- Normal lymph nodes

- typically small (<10 mm in short-axis diameter)

- maintain a flattened oval shape

- Suspicious or metastatic nodes

- ≥10 mm in short-axis diameter is considered pathological

- round shape (loss of normal oval contour)

Margins and echostructure

- Benign/reactive nodes

- well-defined smooth borders

- homogeneous, sometimes thickened hypoechoic cortex with an echogenic hilum (Figure 13)

- Malignant/metastatic nodes

- irregular margins or hyperechogenic ring, as a sign of extracapsular spread due to metastatic involvement (Figure 14)

- non-homogeneous echogenicity, with cystic necrotic areas in advanced disease (Figure 15)

- loss of the central echogenic hilum (a hallmark of malignancy)

13

Pelvic (external iliac) lymph node with cortical thickening, visualized using a convex probe. Color flow represents iliac vessels.

14

Hyperechogenic ring, raising suspicion of metastasis, visualized using a convex probe.

15

Pelvic (external iliac) lymph node, visualized using a convex probe, showing cystic area (dashed circle).

Vascularization (assessed by Doppler imaging)

- Normal/reactive nodes

- central vascular flow limited to the hilum

- regular, symmetric branching pattern

- Suspicious/malignant nodes

- peripheral or mixed vascularity (Figure 16)

- transcapsular flow (vessels penetrating from the periphery towards the center) suggesting tumor infiltration

- chaotic blood flow on power Doppler

16

Pelvic node with mixed vascularization, visualized with a convex probe.

Additional considerations

Normal nodes are mobile, whereas infiltrated nodes may be fixed due to perinodal spread. Calcifications may be seen in treated metastatic nodes or in some infections. Once all the above parameters have been assessed, it remains essential to generate a structured report that includes an overall evaluation of the level of suspicion (Table 2).

2

Example of structured report for describing a suspicious pelvic node.

Parameter | Description |

Location | External/obturatory/internal iliac vessels |

Size | Short and long axis similar in length |

Shape | Round |

Echogenicity | Hypoechoic |

Hilum | Absent (loss of central echogenic hilum) |

Margins | Irregular (a sign of capsular interruption) |

Echotexture | Non-homogeneous |

Vascularization | Peripheral and transcapsular flow (↑ Doppler) |

Mobility | Fixed to adjacent tissues |

Suspicion | Suggestive of metastatic involvement |

CONCLUSION

By using a structured and standardized approach to describing pelvic lymph nodes on ultrasound, gynecologists and oncologists can improve staging accuracy and guide appropriate treatment decisions.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- Use high-frequency linear probes (7.5–14 MHz) to achieve optimal resolution when evaluating inguinal lymph nodes, especially for superficial structures.

- Identify key anatomical landmarks (V sign, snail sign, hill sign) on groin ultrasound examination to ensure consistent orientation and complete regional assessment.

- Always assess both superficial and deep inguinal lymph nodes, locating them relative to the saphenofemoral junction and Camper's fascia.

- Follow a systematic assessment of pelvic lymph nodes, starting with the uterine vessels and tracking along the internal and external iliac arteries up to the vascular lacuna.

- Describe each lymph node using the VITA criteria, which include dimensional (size and ratios), morphological (shape, cortex, echogenicity) and vascular (Doppler) features.

- Pay special attention to cortical thickening, inhomogeneous echostructure, capsular disruption and transcapsular vascularization, as these are strong indicators of metastatic involvement.

- Classify lymph nodes using the LN1–LN5 grading scale, from normal to clearly metastatic, to standardize interpretation across observers and institutions.

- Integrate subjective ultrasound findings with clinical risk factors to guide invasive procedures (e.g. FNA/core biopsy) and surgical planning (sentinel node vs lymphadenectomy).

- Consider ultrasound as a first-line tool for nodal staging in vulvar cancer, particularly due to its accessibility, safety and diagnostic performance in expert hands.

- Document findings in a structured report including location, dimensions, morphology, vascularization and overall suspicion level for each side.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) of this chapter declare that they have no interests that conflict with the contents of the chapter.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

REFERENCES

Sankaranarayanan R, Ferlay J. Worldwide burden of gynaecological cancer: The size of the problem. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;20(2):207–225. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2005.10.007. | |

Saraiya M, Watson M, Wu X, King JB, Chen VW, Smith JS, Giuliano AR. Incidence of in situ and invasive vulvar cancer in the US, 1998–2003. Cancer. 2008 Nov 15;113(10 Suppl):2865–72. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23759. PMID: 18980209. | |

Schuurman MS, Van Den Einden LCG, Massuger LFAG, Kiemeney LA, Van Der Aa MA, De Hullu JA. Trends in incidence and survival of Dutch women with vulvar squamous cell carcinoma. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(18):3872–3880. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.08.003. | |

Noone AM, Howlader N, Krapcho M, Miller D, Brest A, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ CK (eds). Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2015 – SEER Statistics. SEER Cancer Statistics Review. https://seer.cancer.gov/archive/csr/1975_2014/. Published 2017. | |

ONS. Mortality Statistics: Deaths Registered in England and Wales (Series DR), 2014. Off Natl Stat. 2014;2014(November):2015. doi: 10.3390/s140814070. | |

Hampl M, Deckers-Figiel S, Hampl JA, Rein D, Bender HG. New aspects of vulvar cancer: Changes in localization and age of onset. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;109(3):340–345. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.01.041. | |

Oonk MHM, Planchamp F, Baldwin P, Mahner S, Mirza MR, Fischerová D, Creutzberg CL, Guillot E, Garganese G, Lax S, Redondo A, Sturdza A, Taylor A, Ulrikh E, Vandecaveye V, van der Zee A, Wölber L, Zach D, Zannoni GF, Zapardiel I. European Society of Gynaecological Oncology Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Vulvar Cancer – Update 2023. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2023 Jul 3;33(7):1023–1043. doi: 10.1136/ijgc-2023-004486. PMID: 37369376; PMCID: PMC10359596. | |

NCCN vulvar cancer guidelines, Version 1.2025. https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?category=1&id=1476 | |

Garganese G, Collarino A, Fragomeni SM, Rufini V, Perotti G, Gentileschi S, Evangelista MT, Ieria FP, Zagaria L, Bove S, Giordano A, Scambia G. Groin sentinel node biopsy and18F-FDG PET/CT-supported preoperative lymph node assessment in cN0 patients with vulvar cancer currently unfit for minimally invasive inguinal surgery: The GroSNaPET study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2017 Sep;43(9):1776–1783. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2017.06.018. Epub 2017 Jul 16. PMID: 28751058. | |

Van der Zee AG, Oonk MH, De Hullu JA, Ansink AC, Vergote I, Verheijen RH, Maggioni A, Gaarenstroom KN, Baldwin PJ, Van Dorst EB, Van der Velden J, Hermans RH, van der Putten H, Drouin P, Schneider A, Sluiter WJ. Sentinel node dissection is safe in the treatment of early-stage vulvar cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008 Feb 20;26(6):884–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.0566. PMID: 18281661. | |

Pouwer AFW, Arts HJ, van der Velden J, de Hullu JA. Limiting the morbidity of inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy in vulvar cancer patients; a review. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2017;17(7):615–624. doi: 10.1080/14737140.2017.1337513. | |

Collarino A, Garganese G, Fragomeni SM, Pereira Arias-Bouda LM, Ieria FP, Boellaard R, Rufini V, de Geus-Oei LF, Scambia G, Valdés Olmos RA, Giordano A, Grootjans W, van Velden FHP. Radiomics in vulvar cancer: first clinical experience using18F-FDG PET/CT images. J Nucl Med. 2018 Jul 20;60(2):199–206. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.118.215889. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 30030346; PMCID: PMC8833861. | |

Collarino A, Garganese G, Valdés Olmos RA, Stefanelli A, Perotti G, Mirk P, Fragomeni SM, Ieria FP, Scambia G, Giordano A, Rufini V. Evaluation of Dual-Timepoint18F-FDG PET/CT Imaging for Lymph Node Staging in Vulvar Cancer. J Nucl Med. 2017 Dec;58(12):1913–1918. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.117.194332. Epub 2017 May 25. PMID: 28546331. | |

Rufini V, Garganese G, Ieria FP, Pasciuto T, Fragomeni SM, Gui B, Florit A, Inzani F, Zannoni GF, Scambia G, Giordano A, Collarino A. Diagnostic performance of preoperative [18F]FDG-PET/CT for lymph node staging in vulvar cancer: a large single-centre study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021 Sep;48(10):3303–3314. doi: 10.1007/s00259-021-05257-8. Epub 2021 Feb 23. PMID: 33619601; PMCID: PMC8426310. | |

Triumbari EKA, de Koster EJ, Rufini V, Fragomeni SM, Garganese G, Collarino A. 18F-FDG PET and 18F-FDG PET/CT in Vulvar Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Nucl Med. 2021 Feb 1;46(2):125–132. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000003411. PMID: 33234921. | |

Xu X, Li Z, Qiu X, Wei Z. Diagnosis performance of positron emission tomography-computed tomography among cervical cancer patients. J X-Ray Sci Technol. 07 2016;24(4):531–6. | |

Verri D, Moro F, Fragomeni SM, Zaçe D, Bove S, Pozzati F, Gui B, Scambia G, Testa AC, Garganese G. The Role of Ultrasound in the Evaluation of Inguinal Lymph Nodes in Patients with Vulvar Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers (Basel). 2022 Jun 23;14(13):3082. doi: 10.3390/cancers14133082. PMID: 35804853; PMCID: PMC9265034. | |

Garganese G, Fragomeni SM, Pasciuto T, Leombroni M, Moro F, Evangelista MT, Bove S, Gentileschi S, Tagliaferri L, Paris I, Inzani F, Fanfani F, Scambia G, Testa AC. Ultrasound morphometric and cytologic preoperative assessment of inguinal lymph-node status in women with vulvar cancer: MorphoNode study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Mar;55(3):401–410. doi: 10.1002/uog.20378. PMID: 31237047. | |

Fragomeni SM, Moro F, Palluzzi F, Mascilini F, Rufini V, Collarino A, Inzani F, Giacò L, Scambia G, Testa AC, Garganese G. Evaluating the Risk of Inguinal Lymph Node Metastases before Surgery Using the Morphonode Predictive Model: A Prospective Diagnostic Study in Vulvar Cancer Patients. Cancers (Basel). 2023 Feb 9;15(4):1121. doi: 10.3390/cancers15041121. PMID: 36831462; PMCID: PMC9953890. | |

Fischerova D, Garganese G, Reina H, Fragomeni SM, Cibula D, Nanka O, Rettenbacher T, Testa AC, Epstein E, Guiggi I, Frühauf F, Manegold G, Scambia G, Valentin L. Terms, definitions and measurements to describe sonographic features of lymph nodes: consensus opinion from the Vulvar International Tumor Analysis (VITA) group. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2021 Jun;57(6):861–879. doi: 10.1002/uog.23617. PMID: 34077608. | |

Daseler EH, Anson BJ, Reimann AF. Radical excision of the inguinal and iliac lymph glands; a study based upon 450 anatomical dissections and upon supportive clinical observations. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1948 Dec;87(6):679–94. PMID: 18120502. | |

Timmerman D, Valentin L, Bourne TH, Collins WP, Verrelst H, Vergote I; International Ovarian Tumor Analysis (IOTA) Group. Terms, definitions and measurements to describe the sonographic features of adnexal tumors: a consensus opinion from the International Ovarian Tumor Analysis (IOTA) Group. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2000 Oct;16(5):500–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.2000.00287.x. PMID: 11169340. | |

Leone FP, Timmerman D, Bourne T, Valentin L, Epstein E, Goldstein SR, Marret H, Parsons AK, Gull B, Istre O, Sepulveda W, Ferrazzi E, Van den Bosch T. Terms, definitions and measurements to describe the sonographic features of the endometrium and intrauterine lesions: a consensus opinion from the International Endometrial Tumor Analysis (IETA) group. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Jan;35(1):103–12. doi: 10.1002/uog.7487. PMID: 20014360. | |

Harmsen MJ, Van den Bosch T, de Leeuw RA, Dueholm M, Exacoustos C, Valentin L, Hehenkamp WJK, Groenman F, De Bruyn C, Rasmussen C, Lazzeri L, Jokubkiene L, Jurkovic D, Naftalin J, Tellum T, Bourne T, Timmerman D, Huirne JAF. Consensus on revised definitions of Morphological Uterus Sonographic Assessment (MUSA) features of adenomyosis: results of modified Delphi procedure. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2022 Jul;60(1):118–131. doi: 10.1002/uog.24786. PMID: 34587658; PMCID: PMC9328356. | |

Federative Committee on Anatomical Terminology (FCAT). Terminologia Anatomica: International Anatomical Terminology. Georg Thieme Verlag; 1998:300. | |

Fischerova D. Ultrasound scanning of the pelvis and abdomen for staging of gynecological tumors: a review. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;38:246–266. | |

Anatomia. Susan S. Gray’s Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice. 41st ed. Elsevier Ltd.; 2016. | |

Fischerova D, Culcasi C, Gatti E, Ng Z, Burgetova A, Szabó G. Ultrasound assessment of the pelvic sidewall: methodological consensus opinion. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2025 Jan;65(1):94–105. doi: 10.1002/uog.29122. Epub 2024 Nov 5. PMID: 39499650; PMCID: PMC11693842. | |

Fischerova D, Gatti E, Culcasi C, Ng Z, Szabó G, Zanchi L, Burgetova A, Nanka O, Gambino G, Kadajari MR, Garganese G; Collaborators. Ultrasound assessment of lymph nodes for staging of gynecological cancer: consensus opinion on terminology and examination technique. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2025 Feb;65(2):206–225. doi: 10.1002/uog.29127. Epub 2024 Nov 8. PMID: 39513930. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards program CLICK HERE)