Abnormalities of Pelvic Support

Authors

INTRODUCTION

Dealing effectively with the clinical problems of pelvic organ prolapse requires an understanding of the anatomy of those structures that maintain the pelvic viscera in their normal position, and the impact of anatomic alterations on the physiologic mechanisms of support. It is recognized today that the skeletal muscles of the pelvic floor act in a synchronous and synergistic manner with the endopelvic connective tissues. The anatomy of these structures will be reviewed to provide the background necessary to understand the abnormalities associated with pelvic organ prolapse, and their correction.

The present understanding of pelvic support defects derives largely from the studies of Halban and Tandler,1 who challenged Fothergill's2 concept that the connective tissues alone were responsible for the suspension of the pelvic organs. Fothergill arrived at his conclusions on the basis of wide surgical experience that led him to believe significant descent of the uterus occurred only after transection of the cardinal ligaments, structures then held principally responsible for maintaining the uterus within the pelvis. This concept was still widely accepted during the early and mid years of the last century and was supported by Mengert3 and Curtis and colleagues.4 It remained for Berglas and Rubin5 to describe the texture of the connective tissues and, by means of levator myography, the position and configuration of the levator ani muscle in the living woman. Porges and coworkers6 in 1960 drew the analogy between the pelvic supporting structures and a mechanical valve. In their scheme, decompensation of the pelvic valve resulted in defects in pelvic support, while all successful operative procedures succeeded by restoring the integrity of the pelvic valve. Further clinical validation of the importance of muscle support was provided by Ulfelder,7 by Nichols and colleagues,8 and, finally and most convincingly, by DeLancey.9

ANATOMIC CONSIDERATIONS

The Bony Pelvis

In the erect posture, which exaggerates the symptoms of pelvic relaxation, the plane of the pelvic inlet is slanted approximately 50° degrees from the horizontal. The axis of the superior pelvic strait, projected cephalad, meets the anterior abdominal wall at the level of the umbilicus. The inferior strait also is inclined anteriorly (Fig. 1). As a result, the uterus in normal anteversion is directed toward the sacrum and coccyx by any increase in intra-abdominal pressure. During pregnancy the uterus enlarges beyond the confines of the pelvis, and its weight is supported largely by the pubic rami and the anterior abdominal wall. In neither instance is the weight of the uterus directed toward the pelvic outlet.

|

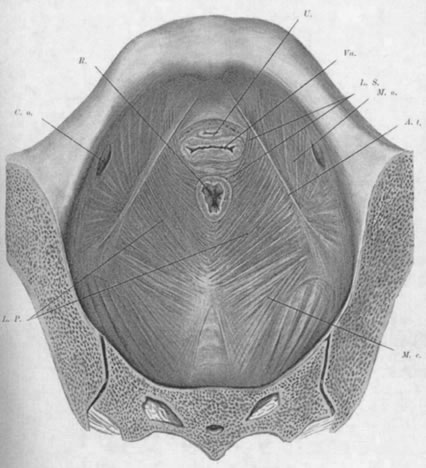

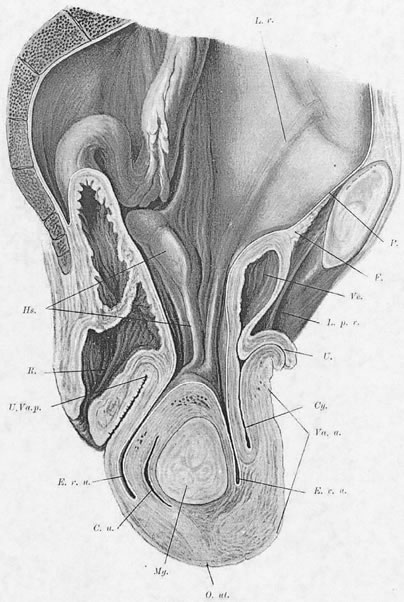

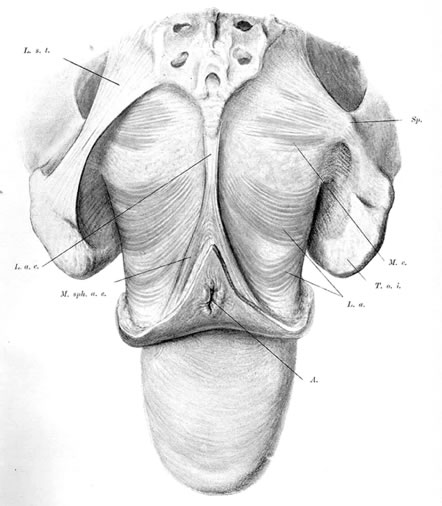

The Pelvic Diaphragm

The pelvic diaphragm, or levator ani muscles, consists of the ischiococcygeal, iliococcygeal, and puborectalis muscles. The latter play an important role in the physiology of the pelvic floor and usually are better developed in the female, being stretched across a wider pelvic outlet. The puborectalis muscles bilaterally arise mainly from the lower surfaces of the pubic bones and from various levels of the obturator fascia; the muscle fibers run posteriorly and caudad, surround the rectum, and unite with fibers from the opposite side, forming a sling around the posterior surface of the rectum. That portion of the muscle posterior to the rectum is called the levator plate; it is distinct from the two lateral levator crura and constitutes the main portion of the levator diaphragm. The free medial edges of the puborectalis muscles are deflected inferiorly and join the rectum and urogenital tract for a short distance in their downward course.

The genital hiatus is the oval opening between the levator crura, through which pass the vagina and urethra. The configuration of the genital hiatus depends on the degree of contraction of the levator ani muscles.

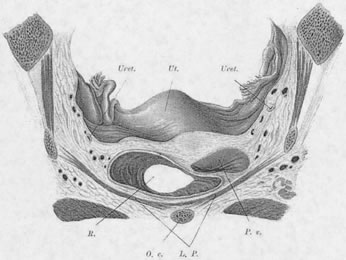

Viewed from above, the pelvic musculature resembles a concave plate. In sagittal section, the nadir of this plate is situated at a point posterior to the genital hiatus and overlying the coccyx. The genital hiatus thus lies not in the deepest portion of the pelvic floor but rather in the anterior, ascending segment (Fig. 2).

Normally, In the erect posture, a projection of the axis of the cervix meets the pelvic floor in the deepest portion of the levator plate, immediately anterior to the coccyx. The greatest part of an anteverted uterus lies posterior to the genital hiatus, resting on the levator plate. Anatomically, the lowest portion of the uterus is situated approximately at the interspinal line; the posterior rim of the genital hiatus lies 6 to 7 cm more anteriorly (Fig. 3).

|

The Perineal Membrane (Urogenital Diaphragm)

The perineal membrane, a fibromuscular triangular plate lying between the pubic rami, extends posteriorly to the anterior rectal wall. It lies inferior to the levator ani muscles and closes the genital hiatus. With the exception of the deep transverse perineal muscles, the urogenital diaphragm contains few muscle fibers. The diaphragm is most susceptible to injury at the point at which it is traversed by the vaginal canal. Because it is composed mostly of fibrous connective tissue, it cannot accommodate well to the distention and dilation that occur during delivery. The levator muscles that surround the genital hiatus are exposed to the same stress but, if intact, can resume normal position and dimensions within a short time. As a result of childbirth, a transient widening of the genital hiatus occurs, while damage to the perineal membrane is more permanent. DeLancey10 best describes the interactions between muscles and connective tissues in the posterior compartment.

Endopelvic Connective Tissue

The space between the pelvic peritoneum and the upper fascial sheaths of the levator ani muscles contains a fibroareolar connective tissue in which are embedded the blood vessels, lymphatic channels, and nerve fibers of the pelvis. In several places this tissue is condensed into thick, fibrous bands identified as pubocervical, cardinal, or sacrouterine ligaments. Strictly speaking, these structures are neither “fascia” nor “ligaments.” The material of which they are composed is not dense but loosely arranged and areolar.11 A preferable term would be endopelvic connective tissue (ECT).

Berglas and Rubin12 demonstrated the absence of ligamentous material in the ECT of two nulliparous cadavers. The region corresponding to the cardinal ligaments contained a plexus of veins embedded in loose areolar connective tissue. It was noted that if these veins were not injected postmortem with latex, they would collapse, causing the muscular walls and fibrous coats of the vessels, on histologic section, to resemble ligamentous structures.

Connective tissue contains fibroblasts that, under inflammatory or mechanical stress, are capable of proliferating into collagenous fibrous tissue. Gestation may accelerate this process in the ECT. If the pelvic floor loses its capacity to support the pelvic viscera, the areolar connective tissue responds by forming fibrous bands along the lines of greatest mechanical stress. By the time of surgery for uterine prolapse, the ECT usually has undergone marked hypertrophy and elongation. Clinically, the degree of connective tissue proliferation is directly proportional to the duration and extent of the prolapse. Normally, the ECT functions only to sheathe vessels and nerves, fill empty spaces, and provide a cover for the pelvic organs; it does not provide appreciable support but acts principally to limit mobility of the uterus within wide physiologic bounds. Connective tissue does not have the functional capacity to resist prolonged and repeated stress (i.e., increases in intra-abdominal pressure) and is invariably permanently deformed thereby.

Anatomic observations at the time of surgical repair, or on cadavers, are subject to misinterpretations. Collapsed veins may give a band of tissues a more “ligamentous” histologic appearance. Breaks in tissue integrity may result from dissections intended to expose the tissues for repair.

Debate continues concerning the composition and function of the ECT: shall we call it fascia or connective tissue? Further, the individual variability in the composition of the ECT often is not appreciated. For example, in a nulliparous woman the ECT may be relatively thin and appear sparse, although functioning well with large components of elastic tissue. In older, parous women with degrees of pelvic organ prolapse, the connective tissues are usually thickened by formation of collagen and reduction of elastic tissue . The density of the ECT represents the body's attempt to compensate for a lack of support. The changes in the ECT are comparable to the changes found in the transversalis fascia adjacent to peritoneal protrusions, as in inguinal or umbilical hernias. The layer of ECT is continuous with the transversalis fascia along the rising anterior abdominal wall.

Berglas and Rubin12 have stated explicitly, based on their histologic studies of these tissues, that there is no recognizable point of attachment of the ECT to the pelvic sidewall. Richardson and associates,13 in cadaver dissections, not only found direct attachment of these tissues to the arcus tendineus but also described recognizable separations of the fascial layers, or tears, which led them to recommend their repair at the time of surgery, with favorable results.

The question of the attachment of the ECT to the sidewall of the pelvis remains unresolved. Does a discrete attachment exist at the arcus tendineus, or is the ECT merely adherent laterally up the pelvic sidewall, over a wide area, along the course of the pelvic blood supply? While the firmness of attachment of one tissue to another cannot be stronger than the weaker of the two tissues, tissues broadly adherent may behave as if they are attached.

PHYSIOLOGY OF PELVIC SUPPORT

The position of the uterus and other pelvic organs depends on the function of the levator ani muscles. By virtue of its variable tonus, muscle tissue is best suited to contain changing volumes and pressure stresses. The pelvic diaphragm, in conjunction with the other muscles that surround the abdominal cavity, forms a physiologic unit; this is shown by the fact that these structures are activated synchronously and synergistically in response to fluctuations in intra-abdominal pressure. The resultant effect of this combined muscular activity depends on which muscle segment is overcome. In coughing, for example, the diaphragm yields; in defecation, the levator plate yields.

When the levator muscle contracts forcibly, the entire pelvic floor is raised slightly and flattened, and the levator hiatus is narrowed as its posterior rim is pulled toward the symphysis. Thus, both sagittal and transverse diameters of the genital hiatus are reduced simultaneously.

The entire abdominal musculature, including the levator muscle, contracts noticeably during sudden increases in intra-abdominal pressure. In defecation, the diaphragm and anterior abdominal wall contract maximally; the levator muscles, although contracting initially, gradually yield. Even as the levators yield, however, their tonus does not diminish appreciably. Activation of the levator ani during defecation protects the closure of the pelvic canal. If the levator muscles simply yielded passively to intra-abdominal pressure, all of the pelvic contents would be displaced caudad with each bowel movement. This actually may occur in patients with spina bifida. Normally, the medial portions of the levator muscles yield only enough to permit defecation.

As long as the uterus is positioned in such a way that intra-abdominal pressure forces it against the levator plate and not toward the levator hiatus, its support is assured.

NORMAL SUPPORT OF THE UTERUS

Parturition alters the integrity of the pelvic floor musculature and the consistency of the ECT. Mechanisms of support, therefore, differ between nulliparous and parous women.

Nulliparous Women

In healthy young, nulliparous women, the ECT forms a loose areolar network to which no significant supportive function can be ascribed. By contrast, barring congenital malformations, the levator muscles usually are in an excellent state of development and the genital hiatus is relatively small. In response to an increase in intra-abdominal pressure, the levator muscles are capable of strong contractions that almost completely close the genital hiatus. The intra-abdominal pressure directs the uterus against the levator plate. Thus, the intact levator muscles support the pelvic viscera adequately and no other form of support is necessary.

Parous Women

Rarely does the genital hiatus resume nulliparous dimensions after childbirth. Both overt damage and occult damage to the puborectalis muscles, which form the inner rim of the genital hiatus, result in an inadequacy of the sphincter-like action. In parous women a secondary mechanism develops to assist in uterine support. Enlargement of the genital hiatus and widening of the introitus shift some of the weight of the uterus to the anterior vaginal wall; here, pressure stress results in hypertrophy of the fibroareolar connective tissue, which may attain a thickness of 1 cm. This hypertrophied, plate-like structure overlaps the lateral crura of the levator muscles and forms an oblique angle with the posterior portion of the muscles. An increase in intra-abdominal pressure results in a valve-like closure of the genital hiatus, replacing the sphincter-like closure no longer possible. The anterior vaginal wall and the thickened ECT form the anterior leaf of this “pelvic valve;”6 the posterior portion is formed by the levator muscles on which the vagina indirectly rests. Occasionally a functional “pelvic valve” mechanism also develops in the nulliparous woman (Fig. 4).

Pathogenesis of Pelvic Relaxation

The essential mechanism in the development of prolapse is the dislocation of inadequately supported pelvic organs by chronic, intermittent elevations of intra-abdominal pressure. Differences in the types of prolapse depend on the size, shape, and position of the uterus with respect to the shape, consistency, and integrity of the pelvic floor (Fig. 5).

During parturition, the puborectalis muscles passing around the posterior aspect of the vagina and terminating anterior to the rectum are most susceptible to injury. Other accessory muscles converging on the perineum may be damaged. If the perineal laceration extends into the rectum and is not repaired, the residual portion of the levator ani muscles is used to compensate for the torn external anal sphincter and to help ensure fecal continence; strengthening the levators acts as a deterrent to prolapse.

Incomplete perineal tears spare the external anal sphincter but compromise the stability and integrity of the central perineal tendon, disrupting its junction with the deep transverse perineal muscles and the bulbocavernosus muscles. This diminishes the support of the posterior rim of the genital hiatus without evoking any compensatory muscle strengthening. More subtly, the anterior fibers of the puborectalis muscles may separate from their osseous insertions on the symphysis and pubic rami during childbirth. This results in a permanent widening in the anterior aspect of the genital hiatus and usually goes unrecognized. The traumatic laceration is followed by devitalization, atrophy of muscle fibers, and replacement by fibrous tissue. The anterior vaginal wall sags between the levator crura, starting the development of a cystocele.

The levator muscles may undergo generalized atrophy and attenuation unrelated to trauma, resulting in a funnel-like descent of the entire pelvic floor. This may be caused by neurogenic disturbances (spina bifida, meningocele, or degenerative neuropathies) or malnutrition. In addition, the levator muscles keep pace with the involution of aging that occurs throughout the body; with increasing age, the muscle mass diminishes and the fascia loses its resilience (Figs. 6 and 7).

The rate at which a prolapse develops is determined by many factors: the force of the intra-abdominal pressure, the obliquity and atrophy of the levator muscles, and the response of the ECT to the increased mechanical stress. In addition, constitutional factors play a major role. Pelvic floor relaxation is rare among black women; at the other extreme are tall, thin, asthenic individuals prone to develop multiple fractures and hernias.

Reports dealing with pelvic organ prolapse often speak interchangeably of the support of the pelvic viscera and suspension of pelvic organs. The two terms are not to be used interchangeably. The pelvic floor musculature is capable of supporting overlying viscera; suspension by the connective tissues occurs only in the absence of pelvic muscle support (Figs. 8).14

|

Diagnosis and Classification of Prolapse

Several of the major subspecialty societies have recently endorsed a method of standardization of terminology of pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. While the nine-point measuring grid of the POPQ system15 has passed the test of validation, it has yet to find wide acceptance. The report details many of the ancillary techniques that should be specified. Physical findings should be observed and recorded separately with the patient at rest and under conditions of maximal straining. The examination is conducted with the patient on an ordinary examining table equipped with heel stirrups. The signs of pelvic relaxation are more pronounced when the patient is standing, but it is awkward and impractical to conduct the examination in this position. Heel stirrups are preferred to knee supports because they permit the patient to strain more effectively.

Initially the patient is observed at rest. The genitalia are inspected and, if no displacement is apparent, the labia are spread gently to expose the vestibule and introitus (Fig. 9). The dimensions of the introitus are measured, the integrity of the perineal body is evaluated, and the approximate size of all prolapsed parts is assessed. Allowance should be made for variations in the appearance of a normal multiparous vagina. Folds of the anterior vaginal wall, visible through a relaxed, parous introitus, should not be labeled automatically as a cystocele. The same precaution applies to the findings on the posterior side. We prefer the term “introitus” to represent the opening of the vagina rather than “hymen,” which is a structure rarely present in our multiparous patients.

|

Next, all prolapsed organs are replaced within the pelvis and the patient is instructed to strain forcibly or cough vigorously. During this maneuver the order of descent of the pelvic structures is noted. The relationship of the pelvic organs at the peak of straining is observed. The position of the external os of the cervix in relation to the vaginal introitus can be estimated or measured. If the cervix does not descend to the introitus, one finger may be inserted into the vagina to determine the degree of anterior displacement. Two fingers should never be used to depress the perineum during this maneuver (Fig. 10) because this tends to enlarge the genital hiatus and negate the actions of the levator ani muscles and the pelvic valve.

All prolapsed organs are again replaced within the pelvis. Two fingers are inserted into the vagina and the patient is asked to close her vagina against the examining fingers. The responsiveness of the levator muscles to command is readily assessed. In addition, with the index and middle fingers in the vagina and the thumb on the vulva, one may estimate the bulk, or sparseness, of the muscles and the distance of the medial borders from the midline, especially anteriorly at the insertion of the muscles at the pubic bone. This evaluation should occur before the patient is under anesthesia.

It is not valid to make a diagnosis of uterine prolapse by applying traction to the cervix with a tenaculum. This maneuver displaces the normally anteverted uterus into the axis of the vagina and misdirects the cervix through the genital hiatus (Figs. 11), thereby not duplicating a life situation in any way. Traction on the cervix may help, however, to anticipate the difficulty of subsequent vaginal hysterectomy.

Two distinct separate categories of uterine prolapse may be distinguished by observing the sequence of descent of the pelvic organs with straining. In “cervix first,” the cervix descends first and is followed by the cystorectocele. In such cases the uterus often is in retroversion and directed along the vaginal canal. The cervix acts as a wedge, preventing closure of the pelvic valve. This variety may occur in nulliparous patients and is often accompanied by cervical elongation. In “cervix last,” with straining the cystorectocele descends before the cervix. This type is commonly found and is usually associated with a wide genital hiatus and a small uterus.

The specific points to measure are specified in the POPQ format. The main idea, common to most systems of classification, is to measure one or the other structures relative to the vaginal introitus. The anterior and posterior vaginal walls, the cervix, and the vaginal vault should be regarded separately. Displacement downward of the perineum should be noted. Normally, there is a concave arc between the perineum and the ischial tuberosities. A convex arc indicates perineal descent, usually in association with relaxation of the pelvic floor.

For many years we have found it convenient to describe16 the position of the external os relative to the vaginal introitus, both at rest and with straining. If the cervical os protrudes beyond the introitus with the patient at rest, the degree of prolapse is marked. If straining is required to bring the cervix beyond the introitus, the prolapse is of only moderate degree. In a prolapse of slight degree, even with straining, the cervix descends only to the introitus. Any lesser degree of descent does not warrant a diagnosis of prolapse. Similar grading may be applied to the different components of the anterior or posterior compartments (i.e., cystocele, rectocele, vaginal vault prolapse, or enterocele).

If protrusion of pelvic contents beyond the vaginal introitus has been present for some time, keratinization and fibrosis of the vaginal wall may make the vaginal walls thicker and inelastic. When the prolapsed parts are replaced within the pelvis during the examination, it may be difficult for an elderly woman in lithotomy position to exert enough intra-abdominal pressure to produce the same degree of vaginal protrusion. Having the patient stand for a few moments, cough, or go to the bathroom suffices to return the prolapse to its former state.

Anterior and Posterior Compartment Defects

A cystocele is a sacculation of the bladder that produces a downward displacement of the anterior vaginal wall, often through a widened introitus. Infrequently, an enterocele also presents as a bulge of the anterior vagina. This is more likely to occur if the woman has had a previous hysterectomy. The term “anterior compartment defect” is used after a preoperative examination when the distinction between cystocele and anterior enterocele is not clear.

Similarly, vaginal protrusions posterior to the uterus, or apical scar line, representing the site where a uterus had previously been removed, are termed defects of the posterior compartment. Most commonly a bulge of the distal posterior vagina results from a rectocele. Protrusions of the upper posterior wall are more likely to represent an enterocele or high rectocele. The demarcation point between these defects is often difficult to determine during an office examination.

MEDICAL TREATMENT

For mild degrees of relaxation, especially in younger women shortly after childbirth, levator muscle exercises, sometimes called Kegel exercises, are helpful in restoring the tone of the muscles of the pelvic floor. Patients should be instructed in the proper exercise technique and should not confuse tightening of the gluteal muscles or increasing intra-abdominal pressure with the proper contraction of the puborectalis muscles. This exercise should be repeated several hundred times a day. As with most forms of physical therapy, better results may be anticipated in younger women than in the elderly, in whom generalized skeletal muscle atrophy has occurred. With all degrees of pelvic relaxation, estrogenic hormones help to improve the condition of the vaginal lining and blood supply and may help to improve minor symptoms. Estrogens alone have little effect in any major degree of pelvic organ prolapse.

Vaginal pessaries, or rings, are today mostly made of vinyl-covered flexible materials and are shaped like a dish or a dish with a stem (Gellhorn). They have a definite place in the management of pelvic relaxation in three specific instances:

- Pregnant women, in whom surgery is contraindicated; it is important to replace a prolapsed cervix lest the part that lies exposed outside the vagina become firm and woody and chronically inflamed, and then fail to dilate during labor.

- In women with chronic eversion of the vagina and resultant stasis ulcers, in preparation for surgery. Three weeks with the vagina back in place and estrogen cream will heal the ulcerations and reduce postoperative morbidity. Persistent vaginal ulcers should be biopsied.

- Most commonly, in aged, medically debilitated women who refuse surgery, or are so ill that any form of operative treatment is considered hazardous. Age alone is not considered a contraindication to surgical repair.

After initial insertion of a pessary, the patient should be seen several weeks later as the dimension of the introitus will have become much smaller and a smaller pessary may be required. Waiting longer may result in further shrinkage of the introital dimensions, causing impaction of the pessary.

SURGICAL TREATMENT

An effective operation should recreate the components of a functioning pelvic valve. The following steps are included in all standard procedures that have achieved a good proportion of successful results:

- Amputation of an elongated or hypertrophied cervix

- Correction of uterine retroversion

- Anterior colporrhaphy

- Posterior colpoperineorrhaphy

Amputation of the hypertrophied cervix permits better apposition of the anterior and posterior vaginal walls. Correction of retroversion re-establishes the proper angle between the axis of the uterus and the vagina. All of these steps help to improve the efficiency of the pelvic valve.

Vaginal Hysterectomy

Vaginal hysterectomy often best satisfies the first two of the above requirements, particularly because the majority of operations for uterine prolapse are done on patients past the menopause. The idea that the uterus represents the “keystone of the supporting arch” of the vagina and that removal of the uterus in patients with marked pelvic relaxation will predispose them to secondary vaginal vault prolapse and postoperative enterocele has been largely negated by proper surgical technique, to be discussed later in detail. After removal of the uterus, the ovaries are easily available for inspection and also may be removed. It has been our policy17 to attempt a complete closure of the peritoneum, leaving the cuff of the vagina open in the midline. This allows egress of blood from bleeding stumps, prevents a closed space for anaerobic infections, and eliminates the likelihood of vault hematomas. By itself, vaginal hysterectomy is not sufficient therapy for pelvic organ prolapse, with the uncommon exception of uterine prolapse, cervix first, with the uterus directed into the axis of the vagina in the absence of any cystorectocele.

Anterior Colporrhaphy

The importance of a well-performed anterior colporrhaphy often is underestimated. Reaching the proper plane between bladder and vagina may be accomplished equally well by a primary incision with a scalpel or by the slightly more tedious method of tunneling with a pair of curved scissors. When developing the vaginal mucosal flaps, as much connective tissue as possible should remain on the undersurface of the bladder. Dissection in the proper plane usually results in the least bleeding. Today, among the several techniques of anterior colporrhaphy, one may attach the vesicovaginal connective tissues to both the arcus tendineus and vaginal mucosa, in a so-called paravaginal repair, or one may elect, especially in more advanced or recurrent cases, to introduce a synthetic mesh between bladder and vagina. In the vast majority of cases we adhere to the more traditional technique of multiple midline plications.18 The placement of sutures should aim to preserve the length of the anterior wall, to ensure efficient overlapping of anterior and posterior walls. The connective tissue plate formed in this manner should be at least 5 to 6 cm long rather than a narrow ribbon.

Posterior Colpoperineorrhaphy

The aim of posterior vaginal repair19 is to reduce a rectocele, suture the levator muscles in the midline anterior to the rectum, repair a deficient perineal body, and correct an existing or potential enterocele. Suturing the levator muscles in the midline increases the length of the levator plate, shortens and narrows the dimensions of the genital hiatus, and improves the competence of the pelvic valve.

When the levator muscles are set wide apart, repair is best done by placing sutures directly through the bulk of the muscle. In sexually active women, these sutures must be placed far enough posterior to prevent introital stenosis. Denser layers of rectovaginal connective tissue are often found only lateral to the rectum, leading to plications from one side to another. At times, dissection in this area reveals an apparent horizontal break in the rectovaginal connective tissues, leading to the placement of a horizontal suture layer, termed a site-specific repair.

Manchester-Fothergill Operation

The Manchester-Fothergill2 operation consists of an amputation of the cervix, retention of the body of the uterus, and a vaginal repair. It has no value, as originally claimed, for maintaining the uterus as the keystone of the pelvic arch. Care must be taken not to amputate too large a portion of the cervix lest cervical incompetence occur in subsequent pregnancies. This operation plays a minor role today in American gynecology, because most women lose their capacity to reproduce long before their pelvic organs have fallen.

Clinical experience has shown that shortening of the cardinal ligaments, by plication or scarring, effectively reduces the degree of prolapse by carrying the vaginal vault or lower uterine segment backward toward the site of origin of the uterine arteries, which arise posteriorly in the pelvis and course downward and medially above the levator muscles in a frontal plane corresponding to the ischial spines, or several centimeters posterior to the posterior rim of the genital hiatus. The effectiveness of the operation depends also on a concomitant anterior and/or posterior colporrhaphy. Shortening of the cardinal ligaments alone is insufficient therapy.

Subtotal Vaginectomy

Subtotal vaginectomy or colpocleisis has been described for the correction of giant prolapse or uterine descensus in the aged. The procedure includes vaginal hysterectomy, separation of vaginal walls from bladder and rectum, excision of at least 75% of the upper vagina, and closure of the genital hiatus by suturing together the medial borders of the levator ani muscles. The considerable sacrifice of vaginal function does not play a major role in this group of women, but its success is not guaranteed because intra-abdominal contents may herniate between the attenuated levator muscle fibers stretched to close over the genital hiatus.

LeFort Operation (Partial Colpocleisis)

The LeFort operation20 obliterates the central portion of the vaginal canal, leaving lateral channels for drainage of any possible uterine or cervical secretions. It may be done under local anesthesia and affords minimal surgical trauma because one need only denude a rectangle of vaginal mucosa from the opposing surfaces of the anterior and posterior vaginal walls. It has a place mostly for women unable to tolerate pessaries and severely debilitated medically (usually those residing in nursing homes). The LeFort operation has several disadvantages, among them leaving in situ a uterus to which normal diagnostic access is denied, and the possible occurrence of urinary incontinence resulting from downward displacement of the urethra by traction of the adhesed anterior and posterior vaginal walls. Many elderly women who would have been offered such an operation in a previous era can now withstand a standard vaginal hysterectomy and plastic repair. In our experience, as an operation for women who are ambulatory and active, it has a high rate of recurrence. The indications for its performance, therefore, have been restricted in recent years.

Vault Prolapse

The most common, serious, long-term consequence of vaginal or abdominal hysterectomy and vaginal plastic repair is recurrence of a cystorectocele in combination with an enterocele and associated descent of the vaginal vault. Increases in intra-abdominal pressure directed against the top of an inadequately supported vagina result in prolapse of the vaginal vault. The term “enterocele” is often used interchangeably with vault prolapse, although not all forms of enterocele include prolapse of the vault. The following factors predispose to the formation of vault prolapse: suturing of the sacrouterine ligaments together anteriorly underneath the bladder, shortening of the anterior vaginal wall, retropubic urethral suspensions (MMK, Burch), improper prophylactic culdoplasty at the time of hysterectomy, or failure to recognize an incipient enterocele resulting from increased overlap of the posterior cul-de-sac with the posterior fornix of the vagina, postoperative pelvic infections after primary repair operations, and constitutional factors.

The frequency of this complication occurs in direct relationship to the severity of the original defect. Recurrences that appear within 1 to 2 years of a repair often are due to faulty technique. Long-term recurrences occasionally follow even the best efforts at repair, depending on the patient's constitution and her level of strenuous physical work. To minimize this complication, several procedures have been described under the heading of prophylactic culdoplasty, emphasizing narrowing of the cul-de-sac by means of plication in the midline of the sacrouterine ligaments, and separation of the posterior fornix from a deep and wide cul-de-sac. During the past few years we have come to rely principally on reduction of the enterocele sac and sacrospinous ligament fixation to maintain both the vaginal vault and cul-de-sac in their normal positions. Long-range follow-up of these patients indicates generally satisfactory results, without appreciable sacrifice of coital function.

The technique of sacrospinous ligament fixation has been described elsewhere by Nichols,21 Morley and DeLancey,22 and Cruikshank and Cox.23 Nonabsorbable sutures are preferred by most, while others report success with polyglycolic materials. The most serious complications of sacrospinous ligament fixation include hemorrhage from a pudendal or hemorrhoidal vessel, injury to a branch of the sciatic nerve (rare), and inadvertent passage of the fixation suture through the wall of the rectum, which always should be ruled out at the conclusion of each operation by a rectal digital examination.

In recent years it has been shown that sacrospinous ligament fixation not only has a place for vault recurrences, but also may be used at the time of a primary procedure when descent is marked. In our experience and that of others, the incidence of recurrence in these cases may be significantly reduced. Rather than terming the indication prophylactic, we add sacrospinous ligament fixation after hysterectomy when excessive mobility of the anterior vaginal wall persists even after removal of the prolapsed uterus and anterior colporrhaphy. To prevent vault recurrences, others have had comparable results with transabdominal sacropexy, or McCall24 culdoplasty sutures.

Experience has shown the importance in all patients of preserving the length of the anterior vaginal wall. The best results occur when a vagina of adequate length and caliber is supported by an intact levator ani muscle. Specifically, attention must be paid to both ends of the vagina. It is well known that pulling the vault of the vagina posteriorly to repair a vault prolapse may cause urinary incontinence, just as correction of incontinence anteriorly may lead to an enterocele and ultimate prolapse of the vaginal vault. Shortening of the anterior vaginal wall may follow retropubic urethral suspension; an improperly performed anterior colporrhaphy; vaginal sacropexy, resulting in relative shortening of the vagina by forcing it to span too great a distance; and reduction of an enterocele and a sacrospinous ligament fixation, in which case the defect at the vault is repaired at the expense of displacing the urethra away from the pubic symphysis, resulting in anatomic urinary incontinence.

Prolapse of the vaginal vault always occurs in connection with an enterocele (otherwise the bulge is defined as a cystocele or a high rectocele), but an enterocele does not necessarily cause prolapse of the vaginal vault. The enterocele may straddle the vault and present as a bulge either anterior or posterior to an otherwise well-supported vault. The location of the vault is defined by a linear scar, representing the former site of the cervix. The terms uterine prolapse and vault prolapse are mutually exclusive. Vault prolapse is a term used to describe descent of the top of the vagina, in the absence of a uterus.

After vaginal repair, if the anterior vagina can be brought easily into contact with the sacrospinous ligament on either side, then vaginal length is sufficient. If not, the top of the vagina may need to be reconfigured by incorporating portions of the redundant vaginal wall from over the exposed enterocele into the anterior vaginal wall.

While there is lack of uniformity in regard to preventing vault prolapse after hysterectomy, Colombo and Milani's25 criteria for matched controls is a comprehensive list of possible etiologic factors: grade of uterine prolapse, age, parity, dystocia (birth weight more than 4000 g, use of forceps or vacuum), menopause, body mass index, previous prolapse surgery, heavy work, constipation, and chronic cough.

Sze and colleagues26 found a lower incidence of recurrent prolapse and lower urinary tract symptoms with a combined abdominal approach than with a combined vaginal approach.

URINARY INCONTINENCE

Women presenting with pelvic organ prolapse may not volunteer symptoms of urinary incontinence. Careful inquiry also may fail to reveal that the patient is aware of incontinence or that there is a potential for incontinence after surgical repair. Thus, patients must be informed of the issue of incontinence and urinary retention that may only occur after surgical repair.

Points to be covered in taking a history in patients with pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence include:

- Number of vaginal deliveries, size of the baby, types of instrumentation, and length of first and second stages of labor

- Previous pelvic operations for correction of one or another form of pelvic organ prolapse and spinal operations for tumors, disks, trauma, and spinal stenosis

- Physical demands normally associated with patient's occupation and exercise routine

- Some details concerning normal physiologic functions (i.e., voiding by sphincter relaxation or Valsalva maneuver; how long does it take the patient to have a bowel movement; degree and duration of pushing required to overcome constipation; chronic respiratory efforts [asthma, smoking])

- Approximate frequency and type of sexual activity

- Drugs that promote urinary frequency and narcotics that inhibit normal bowel function and promote stool impaction.

One must also obtain a careful history of urinary tract symptoms. Which activities promote urinary loss, and under what circumstances will these be aggravated? What strategies are used by the patient to limit incontinence? Has the patient undergone instrumentation or previous operations on the urinary tract? What change in urination or urinary control occurred, if any, after a prior operation?

One should consider preoperative urodynamic studies in patients with previous failed incontinence procedures, or when noticeable disparity occurs between the symptoms of incontinence with which the patient presents to the office and the actual physical findings on examination. An unrepaired cystocele may cause kinking of the urethra and obscure symptoms of incontinence. Replacing the anterior vaginal wall within the pelvis, or temporary insertion of a pessary, may unmask incontinence. These preoperative finding should lead to special efforts at surgery to correct this condition.

Despite seemingly adequate correction of pelvic support abnormalities, as measured by the patient's subjective response, the objective urodynamic measurements may tell a different story. This disparity throws suspicion on our methodology, or may simply indicate that a longer follow-up is necessary.

REFERENCES

Halban J, Tandler J: Anatomie und Aetiologie des Genitalprolapse beim Weibe. Vienna: Wilhelm Braumuller, 1907; translated, Porges RF, Porges JC: Obstet Gynecol 15: 790, 1960 |

|

Fothergill WE: Supports of pelvic viscera: A review of some recent contributions to pelvic anatomy with a clinical introduction. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Emp 13: 18, 1908 |

|

Mengert WF: Mechanisms of uterine support and position. Am J Obstet Gynecol 31: 75, 1936 |

|

Curtis AH, Anson BJ, Ashley FL, Jones T: Blood vessels of the female pelvis in relation to gynecological surgery. Surg Gynecol Obstet 75: 421, 1942 |

|

Berglas B, Rubin IC: Study of the supportive structures of the uterus by levator myography. Surg Gynecol Obstet 97: 677, 1953 |

|

Porges RF, Porges JC, Blinick G: Mechanism of uterine support and the pathogenesis of uterine prolapse. Obstet Gynecol 15: 711, 1960 |

|

Ulfelder H: The normal mechanisms of uterine support and its clinical implications. West J Surg 68: 81, 1960 |

|

Nichols DH, Milley PS, Randall CL: Significance of restoration of normal vaginal depth and axis. Obstet Gynecol 36: 251, 1970 |

|

DeLancey JOL Anatomic aspects of vaginal eversion after hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 166:1717, 1992 |

|

DeLancey JOL: Structural anatomy of the posterior pelvic compartment as it relates to rectocele. Am J Obstet Gynecol 180: 815, 1999 |

|

Weber AM, Walters MD: Anterior vaginal prolapse: Review of anatomy and techniques of surgical repair. Obstet Gynecol 89: 311, 1997 |

|

Berglas B, Rubin IC: Histologic study of the pelvic connective tissues. Surg Gynecol Obstet 97: 277, 1953 |

|

Richardson AC, Edmonds PB, Williams NL: Treatment of urinary incontinence due to paravaginal fascial defect. Obstet Gynecol 57: 357, 1981 |

|

Porges RF, Smilen SW: Long-term analysis of the surgical management of pelvic support defects. Am J Obstet Gynecol 171: 1518, 1994 |

|

Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bo K et al: The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol 175: 10, 1996 |

|

Porges RF: A practical system of diagnosis and classification of pelvic relaxations. Surg Gynecol Obstet 117: 769, 1963 |

|

Porges RF: Vaginal hysterectomy at Bellevue Hospital; an experience in teaching residents. Obstet Gynecol 35: 300, 1970 |

|

Porges RF: Anterior colporrhaphy. In Sciarra JJ (ed): Gynecology and Obstetrics. Philadelphia, Lippincott-Raven, 1996 |

|

Porges RF: Posterior colpoperineorrhaphy. In Sciarra JJ (ed): Gynecology and Obstetrics. Philadelphia, Lippincott-Raven, 1998 |

|

LeFort L: Nouveau procede pour la guerison du prolapsus uterin. Bull Gen Ther 92: 237, 1877 |

|

Nichols DH: Sacrospinous fixation for massive eversion of vagina. Am J Obstet Gynecol 142: 901, 1982 |

|

Morley GW, DeLancey JOL: Sacrospinous ligament fixation for eversion of vagina. Am J Obstet Gynecol 158: 872, 1988 |

|

Cruikshank SH, Cox DW: Sacrospinous ligament fixation at the time of transvaginal hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 162: 1611, 1990 |

|

McCall ML: Posterior culdoplasty: Surgical correction of enterocele during vaginal hysterectomy: A preliminary report. Am J Obstet Gynecol 10: 595, 1957 |

|

Colombo M, Milani R: Sacrospinous ligament fixation and modified McCall culdoplasty during vaginal hysterectomy for advanced uterovaginal prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol 179: 13, 1998 |

|

Sze EH, Kohli N, Miklos JR et al: A retrospective comparison of abdominal sacrocolpopexy with Burch colposuspension versus sacrospinous fixation with transvaginal needle suspension for the management of vaginal vault prolapse and coexisting stress incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 10: 390, 1999 |