This chapter should be cited as follows:

Oyaro IM, Wachira SK, et al., Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.417823

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Gynecology Module

Volume 1

Female genital mutilation

Volume Editor:

Professor Anne-Beatrice Kihara, University of Nairobi, Kenya,

President-elect. The International Federation of Gynecology and Obestetrics FIGO

President, African Federation of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (AFOG)

Chapter

Community Engagement in Addressing Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (FGM/C)

First published: July 2022

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

Primary health care (PHC) provides a broad policy basis for community health, a strategy that was adopted globally as a means of ensuring health for all by the year 2000, and the emphasis in PHC is the role of community participation in health and development.1

In the last two decades, there has been a global consensus that ending female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) contributes largely to achievement of gender equality. The spirit of this commitment was captured in the Beijing Declaration of 19952 and reiterated in the 2015 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), specifically, SDG 5.3.3

A number of declarations and resolutions of the World Health Organization, Regional Office for Africa (WHO, AFRO) and the African Union call upon member states to create enabling environments for community health development, undertake health-system-wide actions, and improve financing of community health programs, including the fight against FGM/C, among other recommendations.4 The United Nations in particular, strives for the full eradication of FGM/C by 2030, following the spirit of Sustainable Development Goal 5.3

As with all other sexual and reproductive health matters requiring a public health intervention, engaging a community in addressing FGM/C, rather than relying on them to be implementers, promotes local ownership, encouraging community participation in problem solving, thus ensuring sustainability of the program/intervention.5,6

COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT AND MOBILIZATION

A community is a group of people with diverse characteristics who are linked by social ties, share common perspectives, and engage in joint action in geographical locations or settings,7 thus influencing their way of life and offering a sense of identity to its members. With regards to FGM/C, four key stakeholders should be addressed in the community: (1) the victims (young girls and women); (2) the perpetrators; (3) the custodians of the community’s tradition/culture (men – most communities are patriarchal; the local and religious leaders); (4) policy makers (health-care providers; civil leaders at local and national level).

As this is a deeply rooted cultural practice that defines a female’s status in society, anti-FGM/C legislation alone curbs a small proportion of the problem and indeed on its own, runs the risk of pushing the practice underground.8,9

One can therefore not successfully implement any long-lasting anti-FGM/C program without wholly involving all stakeholders in the community.

Community engagement entails raising awareness of a health concern and bringing together community resources (human and non-human) to assist in developing a sustainable and self-reliant intervention. This entails targeting different stakeholders at individual, interpersonal, community, and national levels.10

It involves the following steps:

- Community entry – facilitates initial access (stakeholder analysis).

Identifying and involving different stakeholders – the women and young girls, village elders, civic and religious leaders, teachers, local politicians, etc., in discussing the impact of FGM/C on women and the society at large. - Community engagement – enhances ownership.

Learn more about the target community’s socio-cultural views of FGM/C, e.g., a rite of passage into adulthood; a pre-requisite for young girls/women before marriage; a source of status for women in the community; prevents promiscuity. Understand myths, beliefs, and misinformation regarding FGM/C. Use culturally appropriate wording when addressing the community (FGC rather than FGM, is used in certain contexts as a sigh of respect, as argued by some postcolonial feminists, who find the term offensive to those who do not regard themselves as mutilated.11,12 - Community mobilization – addresses the need and achieves results.

Raise awareness through dialog with stakeholders. Empower stakeholders to identify sound interventions, e.g., alternative rites of passage. - Monitoring and evaluation – quantifies the impact of the intervention; community becomes the custodian of their health promotion, preventive strategies, ensures social accountability and demanding provision of services (alternative rites of passage).

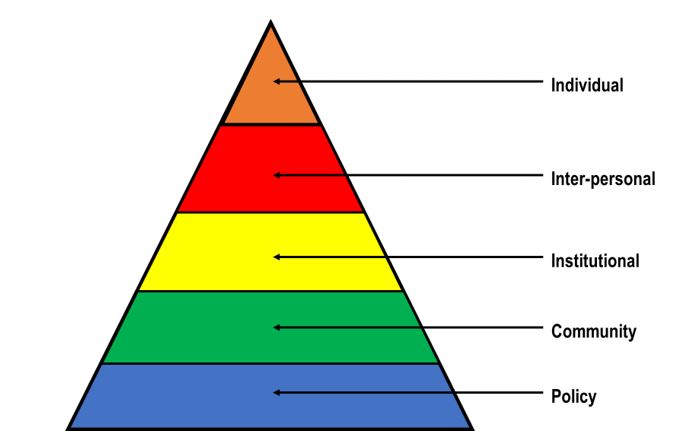

As with all sexual and reproductive health (SRH) programs, assessing/approaching the issue based on the socio-ecological model ensures all stakeholders are well involved in coming up with the solution(s). The tenets of this model are individual-based factors (intrapersonal), interpersonal, institutional factors, community factors as well as societal and policy influences. These different pillars influence the attitudes, behavioral intentions as well as the actual behaviors demonstrated in FGM/C.

At the individual level, the key determinants of engaging in FGM/C behavior are a need for identity and a sense of belonging to one’s community. These factors influence an individual’s attitudes towards seeking or agreeing to FGM/C. Empowering one and building their self-esteem gives one the impetus to fight for their rights. Examples of such self-empowering activities include encouraging girls’ education, girls’ clubs in schools and in the community (train them in sexual and reproductive health; child rights, etc.)

Interpersonal level depicts influence from peers, family members, significant persons as well as other close social circles. The perceived reaction and support from these persons, whether social, financial, or moral may influence the decision made by the woman. Most societies are patriarchal. This indicates the fundamental importance men have in decision making in their households even in matters of women health. Peers have been found to have profound influence on a person’s decision. The desire to fit in and the incremental value placed on peer relationships places impetus to take decisions that are socially appealing amongst the peers. This model is supported by adolescents’ implicit theories on peer relationships. One fears being considered an outcast by family and peers and not being eligible for marriage. The fear of being a social outcast is perhaps the greatest hindrance to effective anti-FGM/C campaigns.15

Talk to mothers in the local health facilities; fathers in local/village meetings on the health hazards of FGM/C to the young girls and encourage them to consider alternative rites of passage.

The impact of social fabric and professional network input into a person’s decision on personal matters cannot be overstated.

Institutional/organizational influence forms a core part of the socio-ecological model. It forms a fundamental pillar of community engagement. Institutional factors that determine the practice of FGM/C or lack thereof rely on the institutional culture that has been cultivated as well as the priority sets and attitudes towards medicalization of FGM/C. The very health workers that should fight FGM/C are sometimes known to offer the practice, thus enticing the community to a "safe FGM/C".13 Some institutions also lack a physical space that is safe, convenient, private, and readily available to offer post-FGM/C care/support to survivors of the practice, e.g., following a botched procedure or if one has obstetric complications following FGM/C. Continual equipping of these institutions with relevant physical resources and frequent skills' appraisal of staff is important. Institutional culture forms the backbone in engaging with the community. Institutions that hold extremist views or reservations on FGM/C may restrict the extent to which the community engages them on matters related to botched FGM/C procedures. Faith-based institutions are known to hold an immovable ground on denying abortion services. These factors depict a communication gap that can be exploited to improve the interdependency of institutions and the community.

At the community level, the norms and values of a community greatly influence an individual’s and community’s perspective of FGM/C as a whole. A rite of passage to initiate girls into womanhood is a well-known tradition of many communities globally. It gives the girl/woman a sense of status in her society and lack of it, almost certainly guarantees ineligibility for marriage and poor social standing in these communities. Encouraging the stakeholders in the community to replace this with acceptable alternative rites of passage therefore is one way of building bridges to save the females from FGM/C without disrespecting their culture.

At the national level, laws and legislations addressing FGM/C should be enacted and implemented with full cognizance of existing socio-cultural ways of the people in the society in question.

The interactions of these various levels within the context of the socio-ecological model are illustrated in Figure 1.

1

Social-ecological model/public health approach. Modified from Mcleroy et al., 1988.14

Community engagement and mobilization should be approached with the above context in mind, as the socio-cultural implications of shunning FGM/C have to be considered.

COMMUNITY MOBILIZATION

ALTERNATIVE RITES OF PASSAGE (ARP) TO FGM/C

These refer to substitute methods of initiating females into womanhood without female genital mutilation or cutting. ARPs are becoming increasingly popular in Africa, e.g., in Kenya and with donors funding global campaigns against FGM/C.16,17

ARPs differ from one community to another but the fundamental principle is to initiate a community approved/recognized transition of a girl into womanhood. Activities involved in the ARPs include training on sexual and reproductive health, child rights, sexual abuse, substance abuse, self-esteem, community specific culture, and harmful traditions. Involving converted former perpetrators (these are usually lay midwives/traditional birth attendants) in leading these ARPs makes them more readily acceptable by the community, thus ensuring a sustainable solution to FGM/C practices.18 This helps in transforming harmful indigenous knowledge systems and implementation science (design, intervention, implementation, and context).

OTHER COMMUNITY MOBILIZATION STRATEGIES

Some of the other community mobilization strategies to ameliorate FGM/C include but are not limited to the following:

- Education of girls.

- Capacity building of NGO (e.g., AMREF)/local communities and gatekeepers.

- Safe spaces (shelters for girls ostracized by communities for refusing FGM/C).

- Safe-guarding linkage to SRHR services (community health workers to target adolescent girls and their mothers and linking them to community health facilities for continuous SRH guidance).

- Engaging the custodians of a community’s traditions and culture, e.g., male engagement.

- Advocacy champions.

RESOURCE MOBILIZATION IN ADDRESSING FGM/C

Resource mobilization refers to all activities aimed at securing new and additional resources for an organization/cause. It also involves maximizing the use of existing resources.

All social movements are driven by theorists and activists who clamor for change. Political change is usually socially structured and as such resources available to activists are organized according to the social structures.

Resource mobilization theory is a study on social movements that seeks to show that causes will succeed or fail based on the resources available and the ability to use these resources.19 It focuses on how movements are organized then succeed or fail, rather than why they exist. (Previous studies on social movements were mainly on why people join them, e.g., pro-life vs. pro-choice factions in the abortion debate.)

It emphasizes strategies that maximize the resources that are already available to the activists and minimizes the reliance on resources that are not readily available to enhance success of the proposed changes.20

The traditional view is on resources being financial, but there is a need to also consider knowledge and perspective as resources that also need to be mobilized and organized optimally for achievement of the goal.20 Five categories of resources have been described: material, human, social-organizational, cultural, and moral. These are described below.19

- Material resources: these are the tangible resources (such as money, a location for the organization to meet, and physical supplies) necessary for an organization to run. Material resources can include anything from supplies for making protest signs to the office building where a large non-profit is headquartered.

- Human resources: this refers to the labor needed (whether volunteer or paid) to conduct an organization's activities. Depending on the organization's goals, specific types of skills may be an especially valuable form of human resources. For example, an organization that seeks to increase access to health care may have an especially great need for medical professionals, while an organization focused on immigration law may seek out individuals with legal training to get involved in the cause.

- Social-organizational resources: these resources are ones that SMOs can use to build their social networks. For example, an organization might develop an email list of people who support their cause; this would be a social-organizational resource that the organization could use itself and share with other SMOs that share the same goals.

- Cultural resources: cultural resources include knowledge necessary to conduct the organization's activities. For example, knowing how to lobby elected representatives, draft a policy paper, or organize a rally would all be examples of cultural resources. Cultural resources can also include media products (for example, a book or informational video about a topic related to the organization's work).

- Moral resources: moral resources are those which help the organization to be seen as legitimate. For example, celebrity endorsements can serve as a type of moral resource: when celebrities speak out on behalf of a cause, people may be spurred to learn more about the organization, view the organization more positively, or even become adherents or constituents of the organization themselves.

Several resource mobilization strategies have been described in a paper by Abdul-Wahab and colleagues for Wa municipality council in Ghana that were aimed at providing resources to tackle various developmental challenges. The strategies included publicity and sensitization, issuance of demand notices, door-to-door collection, investment, privatization and outsourcing, and lobbying. The most effective strategy was found to be door-to-door collections, with investment being the least effective due to challenges in accounting and management strategies.21

How the organization utilizes the resources is also part of the resource mobilization theory. This may be influenced by factors such as from whom the resources have been gotten from, as there may be pre-conditions to accessing the resources.19 This is explained in the resource dependence theory and measures should be taken to reduce the impact of these external influences.22

It is important to remember that the goal of driving a social change is never a 100% win with complete destruction of the opposing camp, but rather to achieve a mutually negotiated middle ground with the opposing parties.20

MONITORING AND EVALUATION

The process and progress of anti-FGM/C programs should continuously be assessed to determine the effectiveness of the interventions. Planning for any intervention is therefore incomplete without clear mechanisms for collectively monitoring and evaluating.23 This forms the basis for tracking progress and performance of national health policies, strategies and plans (NHPSP), and to inform the health policy dialog.24

SOCIAL ACCOUNTABILITY

Social accountability means holding duty bearers – politicians, public officials (civic, political and to an extent, religious leaders) to account for their actions and performance regarding existing and emerging social concerns and priorities based on need.25 Citizens have a right to demand accountability from office bearers at the community and national level in the fight against FGM/C.

It demands effective and open communication with communities so that they can participate in the process. It involves the following:

- Public information-sharing.

- Policy-making and planning.

- Analysis and tracking of public budgets, expenditures, and procurement processes.

- Participatory monitoring and evaluation of public service delivery, as well as broader oversight roles.

- Anti-corruption measures and complaint-handling mechanisms.

PESTELE ANALYSIS: A SITUATION ANALYSIS TOOL FOR COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT AND MOBILIZATION IN ADDRESSING FGM/C

This is an acronym for a method of analyzing the macro (external) factors that affect an organization. They stand for

political, economic, social, technological, environmental, legal, and ethical.

Prior to implementation of any strategies, a situation analysis is usually needed and PESTELE forms a part of this. The components are described below.26

- Political factors: these determine the extent to which government and government policy may impact on an organization or a specific industry. This would include political policy and stability as well as trade, fiscal, and taxation policies too.

- Economic factors: these factors impact on the economy and its performance, which in turn directly impacts on the organization and its profitability. Factors include interest rates, employment or unemployment rates, raw material costs, and foreign exchange rates.

- Social factors: these factors focus on the social environment and identify emerging trends. This helps a marketer to further understand their customers’ needs and wants. Factors include changing family demographics, education levels, cultural trends, attitude changes, and changes in lifestyles.

- Technological factors: these factors consider the rate of technological innovation and development that could affect a market or industry. Factors could include changes in digital or mobile technology, automation, research and development. There is often a tendency to focus on developments only in digital technology, but consideration must also be given to new methods of distribution, manufacturing, and also logistics.

- Environmental factors: these factors relate to the influence of the surrounding environment and the impact of ecological aspects. With the rise in importance of corporate sustainability responsibility (CSR), this element is becoming more important. Factors include climate, recycling procedures, carbon footprint, waste disposal, and sustainability

- Legal factors: an organization must understand what is legal and allowed within the territories they operate in. They also must be aware of any change in legislation and the impact this may have on business operations. Factors include employment legislation, consumer law, health and safety, international as well as trade regulation and restrictions. Political factors do cross over with legal factors; however, the key difference is that political factors are led by government policy, whereas legal factors must be complied with.

- Ethical factors: this is a new addition to the traditional PESTELE framework. These factors dwell on the consideration of the ethical implications of an organization’s activity. These may include the medical ethics of the following: autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice among others. It also involves matters such as fair trade, slavery acts and child labor, as well as CSR, where a business contributes to local or societal goals such as volunteering or taking part in philanthropic, activist, or charitable activities.27

A related and broader concept is social responsibility. It means individuals and organizations behaving and acting for the benefit of, or at least not causing harm to, society at large.

Research is another important tool of evaluation. As it stands, there is a paucity of data to objectively evaluate the real impact of community engagement and mobilization in addressing FGM/C as compared to other interventions. Governments should prioritize and mobilize resources into research to address gaps in policies and programs, as a way of continuously evaluating community-based programs currently in place.28

CONCLUSION

Community engagement and mobilization should be at the center of addressing FGM/C if we are to achieve an FGM/C-free world by 2030 as per Sustainable Development Goals.29

IMPACT OF COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT AND MOBILIZATION ON DEVELOPMENT WITH FEMALE GENITAL MUTILATION/CUTTING (FGM/C)

A community as described earlier refers to a group of individuals of diverse characteristics in a geographical region that are bound together and identify with common beliefs, practices, and attitudes on various topics of day-to-day life.7 They thus have similar practices when it comes to their health. Most of these beliefs and practices have been passed down through generations. Engaging them in the fight against FGM can have significant impact with tangible gains as outlined below.

Primary health care as enshrined in the Alma Ata declaration of 1978 has health promotion as its core and involves measures targeted at the community level.30 The SDGs at international level put health under the social pillar and Kenya’s second National Health Sector Strategic Plan (NHSSP II: 2005–2010) at country level defined a new approach to the way the sector would deliver health-care services to Kenyans, shifting the emphasis from burden of disease to the promotion of individual and community health.31

Health interventions for individuals and communities have been shown to work best when the targeted persons are involved in identifying the problems and crafting the solutions for the same. This forms the basis for community engagement and mobilization for health interventions including those aimed at ending female genital mutilation/cutting.32

This is especially true for anti-FGM health strategies because most have been found to focus on selling the anti-FGM message on the basis of FGM being harmful to women’s health, but ignoring the values, myths, and enforcement mechanisms at community level that perpetuate the practice.33

The impact of community engagement when dealing with FGM is well documented. First and foremost is that it allows an understanding of why communities have certain practices. This is important for health-care workers, those running health programs and even governments in interacting and attempting to influence communities to change. It allows the health-system actors to understand the beliefs, attitudes, and values that perpetuate the practice. It also enables the actors to clarify their own values and attitudes towards FGM that may stand in the way of their service delivery or interaction with communities.34 It also helps in understanding how to best communicate to the communities and craft messages for their consumption. It also has an impact in helping communities examine their own beliefs, attitudes, and practices, and make decisions on what to change and retain. This is opposed to receiving haughty prescriptions on their behavior from outsiders.34

Involving the community also means involving and engaging with the local, religious, government, and political leaders. This is because of the key role they have in influencing behavior in the communities they represent. This results in macro-level support in terms of enabling policies and laws being crafted to aid in ending FGM. It also means resources (budgets) can be channeled towards activities that support the push towards ending FGM. It also means the anti-FGM message can be incorporated into the broader education and health programs for greater reach. Overall this translates into greater success for programs aimed at ending FGM.34,35,36

Involvement and working with mass media to reach communities also has an impact in enabling the message to reach a larger audience in the community. It also established that media contributes to shaping and changing beliefs, attitudes, values, and practices in societies. Leaders, mass media can also be recruited into advocacy and lobbying to enhance the messages to end FGM in communities.37

The impact of community engagement can also be seen at the global level where involvement of communities that do not traditionally practice FGM has an impact at the international level. This is because with the world become a global village as a result of migration and as a result the practice has spread to regions of the world that do not traditionally practice FGM. In these settings there also needs community engagement, laws, and policies to stem the practice and protect vulnerable members especially minors who may fall victim to FGM.38

In summary, community engagement strategies at the local and international levels can have great impact in helping the communities to abandon the practice on their own volition, but also to protect those who may be at risk.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- Community engagement and mobilization is a strategy that can help communities clarify values and reconsider harmful practices, i.e., FGM/C.

- It also benefits health-care actors to understand the background factors that perpetuate the practice and where they can have impact.

- Stakeholders should be identified in the target community with a purpose to engage them with the aim of leaving no one behind in the fight against FGM/C. This enhances community ownership of the interventions, thus ensuring lasting solutions.

- Community-led alternative rites of passage are a proven method of mobilizing different stakeholders in ending FGM/C in a community.

- It should be targeted to have impact beyond the local and at the international level because migration has led to international spread of the practice.

- Engagement should also involve leaders and the media for greater reach.

- Continuous monitoring and evaluation (including research) is of utmost importance in determining the success of any intervention.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) of this chapter declare that they have no interests that conflict with the contents of the chapter.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

REFERENCES

World Health Organization. Primary Health Care: Declaration of Alma Alta. Lancet 1978. | |

The United Nations. Beijing declaration and platform for action. Fourth World Conference on Women 1995. | |

United Nations. Sustainable Development Goal 5: Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls. Sustain Dev Knowl Platf 2016. | |

The world health report 2000 – Health systems: improving performance. Bull World Health Organ 2000. | |

Mirghani Z, Karugaba J, Martin-Achard UNHCR Chi-Chi Undie N, et al. Community Engagement in SGBV Prevention and Response: A Compendium of Interventions in the East & Horn of Africa and the Great Lakes Region. Popul Counc Inc 2017. | |

UNICEF. The Dynamics of Social Change: Towards the abandonment of female genital mutilation/cutting in five African countries. UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre 2010. | |

MacQueen KM, McLellan E, Metzger DS, et al. What is community? An evidence-based definition for participatory public health. Am J Public Health 2001;91(12):1929–38. | |

Berer M. The history and role of the criminal law in anti-FGM campaigns: Is the criminal law what is needed, at least in countries like Great Britain? Reprod Health Matters 2015. | |

Plugge E, Adam S, El Hindi L, et al. The prevention of female genital mutilation in England: what can be done? J Public Health (Oxf) 2019. | |

Berg RC, Denison E. Interventions to reduce the prevalence of female genital mutilation/cutting in African countries. Campbell Syst Rev 2012. | |

Njambi WN. Dualisms and female bodies in representations of African female circumcision: A feminist critique. Fem Theory 2004. | |

Leye E, Deblonde J, García-Añón J, et al. An analysis of the implementation of laws with regard to female genital mutilation in Europe. Crime, Law Soc Chang 2007. | |

Kimani S, Kabiru CW, Muteshi J, et al. Female genital mutilation/cutting: Emerging factors sustaining medicalization related changes in selected Kenyan communities. PLoS One 2020. | |

Mcleroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, et al. An Ecological Perspective on Health Promotion Programs. Heal Educ Behav 1988. | |

Shakirat GO, Alshibshoubi MA, Delia E, et al. An Overview of Female Genital Mutilation in Africa: Are the Women Beneficiaries or Victims? Cureus 2020. | |

Hughes L. Alternative Rites of Passage: Faith, rights, and performance in FGM/C abandonment campaigns in Kenya. Afr Stud 2018. | |

Chege J, Askew I, Liku J. An assessment of the alternative rites approach for encouraging abandonment of female genital mutilation in Kenya. Reprod Health 2001. | |

Van Bavel H. The ‘Loita Rite of Passage’: An alternative to the alternative rite of passage? SSM – Qual Res Heal 2021. | |

Crossman A. What Is the Resource Mobilization Theory? Thought.co 2020. | |

Rootes C a. Theory of Social Movements: Theory for Social Movements? Philos Soc Action 1990;16(4):1–12. | |

Abdul-Wahab S, Haruna I, Nkegbe PK. Effectiveness of resource mobilisation strategies of the Wa municipal assembly. J Plan L Manag 2019;1(1):60–79. | |

Hillman AJ, Withers MC, Collins BJ. Resource dependence theory: A review. J Manage 2009;35(6):1404–27. | |

Monitoring E, Health P, Interventions C, et al. Effective Monitoring and Evaluation of Primary Health Care Interventions Requires Participatory Approach. J Adv Med Pharm Sci Vol J Adv Med Pharm Sci 2010. | |

WHO. Monitoring, evaluation and review of national health strategies: A country-led platform for information and accountability. Strateg Natl Heal 21st century a Handb 2011. | |

Fox JA. Social Accountability: What Does the Evidence Really Say? World Dev 2015. | |

Oxford College of Marketing. What is a PESTEL analysis? – Oxford College of Marketing Blog. Oxford College of Marketing, 2016;1. | |

Academy P. Marketing Theories – PESTEL Analysis. Prof Acad 2020;1–6. | |

Strachan JM. A commentary: Using a theory-based approach to guide a global programme of FGM/C research: What have we learned about creating actionable research findings? Eval Program Plann 2021. | |

In focus: Women and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): SDG 5: Gender equality | UN Women – Headquarters. | |

Beard TC, Redmond SR. DECLARATION OF ALMA-ATA. The Lancet 1979:313;217–8. | |

House A. Reversing the Trends The Second National Health Sector Strategic Plan Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation Ministry of Medical Services 2009. | |

Corbin JH, Oyene UE, Manoncourt E, et al. A health promotion approach to emergency management: effective community engagement strategies from five cases. Health Promot Int 2021;36(Suppl 1):i24–38. | |

WHO. Policy brief: Female genital mutilation programmes to date : what works and what doesn’t. Who/Rhr/1136 2011;1:1–6. | |

Who. Female Genital Mutilation: A Teacher’s Guide 2001;1–144. | |

Shim H, Shin N, Stern A, et al. The Role of the Church in Ending Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting in order to Promote the Flourishing of Women: A Case Study of the Wolaita Kale Heywet Church, Southern Ethiopia. Adv Opt Mater 2018;10(1):1–9. | |

Johansen REB, Ziyada MM, Shell-Duncan B, et al. Health sector involvement in the management of female genital mutilation/cutting in 30 countries. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18(1):1–13. | |

Wogu JO, Amonyeze C, Babatola Folorunsho RO, et al. An Evaluation of the Impact of Media Campaign Against Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) in the Rural Communities of Enugu State, Nigeria. Glob J Health Sci 2019;11(14):37. | |

Middelburg A. Analysis of Legal Frameworks on Female Genital Mutilation in Selected Countries in West Africa. United Nations Popul Fund 2017;1–132. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards program CLICK HERE)