This chapter should be cited as follows:

Mascilini F, Dababou S, Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.419683

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Gynecology Module

Volume 10

Ultrasound in gynecology

Volume Editors:

Professor Antonia Testa, Agostino Gemelli University Hospital, Rome, Italy

Professor Simona Maria Fragomeni, Agostino Gemelli University Hospital, Rome, Italy

Chapter

Ovarian Masses in Pregnancy: Ultrasound Features and Management

First published: December 2025

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

Ovarian masses are frequently detected in women of reproductive age, often as incidental findings during routine ultrasound examination in asymptomatic individuals. The reported prevalence of adnexal masses in pregnancy varies widely,1,2,3 reflecting differences in screening practices and populations studied. The observed increase in frequency of adnexal masses in pregnancy is largely attributable to the widespread use of antenatal ultrasound, as most masses are asymptomatic and not identified by physical examination.1,2

Most ovarian masses diagnosed during pregnancy are benign physiological cysts that tend to resolve spontaneously without requiring intervention. Although rare, ovarian cancer represents one of the five most common malignancies diagnosed in pregnancy, with the majority of cases identified at an early stage and therefore associated with a relatively favorable prognosis.4

Most sonographic features resemble those in non-pregnant women,3 but pregnancy-related physiological changes may alter their appearance and course, and complicate diagnosis. The implications of accurate sonographic characterization are particularly relevant in pregnancy, as management decisions must balance the risks of surgery for both mother and fetus against the potential complications of adnexal masses. Conservative management is preferred when benign features are confidently identified, while surgical intervention is reserved for suspected malignancy or acute complications.5

In this chapter we focus on the role of ultrasound in the assessment of adnexal masses during pregnancy. It summarizes the most relevant sonographic features of benign and malignant lesions, highlights pregnancy-related changes that may mimic malignancy, and discusses how these findings guide clinical decision-making between expectant and surgical management.

SONOGRAPHIC FEATURES

The widespread use of antenatal ultrasound and first-trimester screening has increased the rate of detection of adnexal masses early in pregnancy.

Benign masses

Most adnexal masses identified during first-trimester ultrasound are physiological cysts related to pregnancy, such as follicular, corpus luteum or hemorrhagic cysts.6 The majority of these resolve spontaneously during gestation,7 while others, particularly larger cysts or those with complex features, tend to regress within 6 weeks postpartum.4,5 However, adnexal masses present before pregnancy and those that persist beyond the postpartum period may indicate underlying pathology.6

Benign formations often show the same morphology as those in non-pregnant women. For example, dermoid cysts (mature teratomas) are the most common ovarian masses detected in women beyond 16 weeks of gestation. Among those requiring surgical management or removal at the time of cesarean delivery, dermoid cysts are the most frequently encountered (32%), followed by serous and mucinous cystadenomas (19%), endometriomas (15%) and functional cysts (12%).3

Dermoid cysts exhibit characteristic ultrasound features, including hyperechoic nodules, acoustic shadowing, hyperechoic lines, and fluid levels.8 Outside of pregnancy, they have been shown to grow slowly, with an average growth rate of 1.67–1.8 mm per year.9 In a prospective study examining dermoid cysts in pregnancy, no significant increase in size or complications, such as cyst rupture or torsion, were observed.10

Rupture and torsion should be suspected in the presence of abdominal pain. However, dermoid cysts can also present with unusual manifestations and have been associated with rare syndromes, such as autoimmune hemolytic anemia11 and anti-NMDAR encephalitis.12,13 Although rare, these cysts have the potential to undergo malignant transformation, most commonly into invasive squamous cell carcinoma.10,14,15

Endometriomas are another common adnexal mass encountered during pregnancy. They account for 4–8% of ovarian cysts identified during routine first-trimester sonography.16,17 In non-pregnant premenopausal women, they are typically described as unilocular or multilocular (1–4 locules) cysts with ground-glass echogenicity and no solid components.18 However, in pregnancy, endometriomas may present as unilocular-solid or multilocular-solid cysts due to decidualization, a phenomenon that can mimic malignancy.

During pregnancy, the endometrium undergoes decidualization, with increased glandular epithelium and stromal vascularity, creating optimal conditions for embryo implantation.19 A similar process occurs in ectopic endometrial tissue within the walls of endometriomas, leading to the development of solid, vascularized areas on ultrasound, resembling papillary projections.

According to the literature, decidualized endometriomas account for about 12–31% of ovarian endometriomas during pregnancy.19,20 These lesions with vascularized papillary projections, may complicate the differential diagnosis with malignancy and, consequently, the management strategy, raising the dilemma between surgical intervention and conservative follow-up.21

Mascilini et al. retrospectively collected data on women who underwent surgery for ovarian cysts with papillary projections but without other solid components. Their study found that a smooth contour of papillations (79% vs. 27%) and ground-glass echogenicity (74% vs. 13%) were more commonly associated with benign rather than malignant adnexal masses.21 Interestingly, the decidualized endometriomas appeared more vascularized on color and on power Doppler than did borderline tumors.21 In a rare case, decidualized endometrioma was described as a solid ovarian mass, with no identifiable healthy ovarian tissue. Ultrasound-guided fine-needle biopsy was performed, confirming decidualized endometriotic tissue without atypia.22

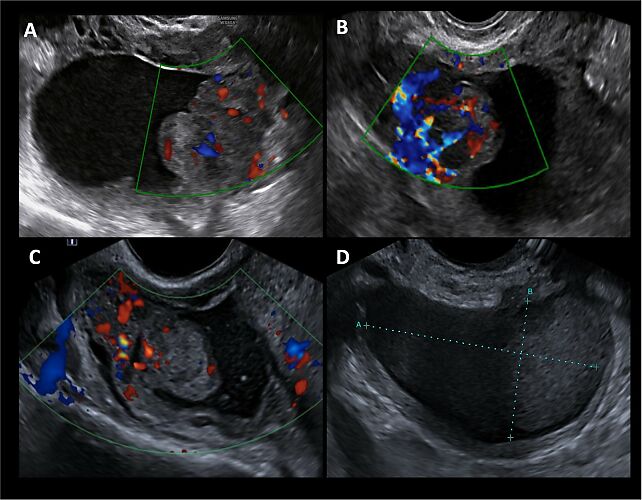

The high rate of spontaneous resolution highlights the suitability of conservative management, consistent with previous studies showing that decidualization typically resolves postpartum, thereby reducing the need for immediate intervention21 (Figure 1).

1

Transvaginal ultrasound images (color Doppler and B-mode) of a known endometrioma at different gestational ages: (A) 12 weeks of gestation; (B) 24 weeks of gestation; (C) 37 weeks of gestation; (D) postpartum. The color Doppler images (A–C) show a unilocular solid cyst with ‘ground-glass’ content, regular external margins and irregular internal margins due to the presence of a vascularized papillary projection. The vascularization of the papilla increases during early pregnancy, reaching a peak at 24 weeks, and then decreases in the third trimester. The papilla maintains a smooth and regular contour throughout gestation. The postpartum scan (D) shows resolution of the papillary structure and reappearance of the typical endometrioma features. This case illustrates a transient, pregnancy-related vascularized papillary projection within an endometrioma, which spontaneously regressed after delivery.

Decidualization of endometriomas is a benign, temporary and dynamic process unique to pregnancy, distinguishing it from the irreversible neoplastic changes associated with malignancy. However, further research is needed to better characterize this phenomenon and improve the ability to differentiate benign decidualization from true malignancy.

Malignant and borderline tumors

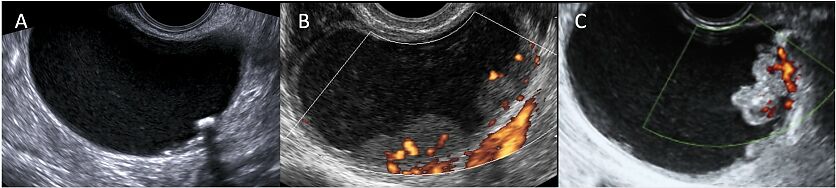

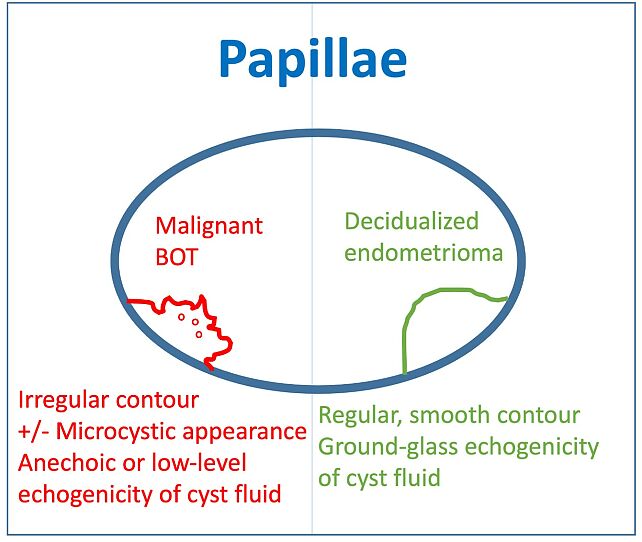

Borderline ovarian tumors (BOTs) are more prevalent among women of childbearing age, with about one-third of cases diagnosed in women under 40 years of age.23 BOTs account for 3–8% of adnexal masses diagnosed during pregnancy17 and represent the most common ovarian malignancy encountered in this setting. On ultrasound, features commonly associated with BOTs include uni- or multilocular ovarian cysts with vascularized papillary projections and/or solid components. A distinct 'microcystic appearance', characterized by tiny 1–3-mm cysts that create a soapy-water or miniature-bubble effect, has been described as a suggestive pattern of BOTs24 (Figure 2). Papillary projections with irregular contours and anechoic or low-level echogenic cyst fluid may further aid in differentiating BOTs from other adnexal masses21 (Figure 3). However, as previously described, the sonographic appearance of BOTs can overlap with that of decidualized endometriomas, making the distinction between benign and malignant masses particularly challenging in pregnancy.21,25,26 In patients with a unilocular solid cyst characterized by papillary projections with an irregular surface, especially when detected in early pregnancy with no evidence of morphological changes during the first half of pregnancy, a borderline histology should be considered.27

2

Transvaginal ultrasound images (B-mode and color Doppler) of unilocular solid masses evaluated during pregnancy: (A) cystadenofibroma; (B) endometrioma; (C) serous borderline ovarian tumor. These images allow the comparison of different types of papillary projection: (A) the papillary projection appears regular, hyperechoic and associated with posterior acoustic shadowing; (B,C) both papillary projections show moderate vascularization on color Doppler; however, the papilla in (B) has a smooth and regular contour, whereas the papilla in (C) has an irregular contour.

3

Ultrasonographic features of papillary projections in ovarian cysts: comparison between malignant borderline ovarian tumors (BOT) and decidualized endometriomas. Malignant BOTs typically exhibit irregular contours, possible microcystic patterns, and anechoic or low-level echogenic cyst fluid. In contrast, decidualized endometriomas are characterized by smooth, regular papillary contours and ground-glass echogenicity of the cyst fluid.

In a retrospective study of 22 patients, Moro et al. reported that the morphological features of malignant ovarian tumors detected by ultrasound during pregnancy are comparable to those observed in non-pregnant women.28 The authors highlighted that any solid adnexal mass, except for ovarian fibroma, should raise the suspicion of malignancy.

Differential diagnosis during pregnancy

According to the findings of Moro et al., certain ultrasound patterns may help differentiate invasive from borderline tumors: unilocular-solid or multilocular-solid cysts with small papillary projections are more often associated with borderline tumors, whereas multilocular-solid tumors with large solid components are typical of invasive epithelial tumors. In addition, solid masses with marked vascularization may be indicative of metastatic disease.28 Ovarian malignancy is a rare complication in pregnancy, the overall incidence being in the range of 0.2–3.8 per 100,000 pregnancies.27,29,30 A population-based study analyzing nearly 5 million obstetric patients identified 9375 pregnant women with an adnexal mass, among whom 87 cases of ovarian malignancy were diagnosed.31 Malignancy in pregnancy is more likely to be of earlier stage and lower grade and is associated with more favorable outcomes than that diagnosed outside of pregnancy.3

1

Sonographic characteristics/pitfalls in the evaluation of ovarian masses during pregnancy.

Decidualized endometrioma | Can mimic borderline tumors due to vascularized papillary projections; smooth surface and ground-glass echogenicity favor benignity. |

Corpus luteum cyst | May appear thick-walled and hypervascular (‘ring of fire’); important not to misinterpret as malignancy. |

Hemorrhagic cyst | Internal echoes and clot retraction can resemble solid components; follow-up scans show resolution. |

Dermoid cyst (mature teratoma) | Echogenic nodules, shadowing and fluid–fluid levels are classic features; atypical presentations may be confusing. |

Borderline ovarian tumor vs decidualized cyst | Microcystic papillae and irregular contours suggest borderline ovarian tumor, whereas smooth papillae point toward decidualization. |

Malignant mass | Typical sonographic features are: papillary projections (irregular contour) with anechoic/low-level echogenicity of the cyst; irregular margins or septations; multilocular cysts, unilocular-solid or multilocular-solid cysts; solid masses |

Other considerations | |

Over-reliance on CA 125 | Physiologically elevated in pregnancy; not reliable for distinguishing between benign and malignant lesions. |

False reassurance from stability | Some borderline tumors may remain morphologically stable in early pregnancy; careful follow-up is warranted. |

MANAGEMENT ALGORITHMS

The management of ovarian cysts in pregnancy may be either conservative (ultrasound surveillance) or surgical. Careful evaluation is required to balance the risks associated with surgery against the potential complications related to adnexal masses. The decision to undertake surgical intervention should be tailored to clinical and ultrasound findings, as well as obstetric considerations such as gestational age and comorbidities. Surgery is primarily indicated in the presence of suspected malignancy or significant symptoms, and for symptomatic patients it may be required at any gestational age (Figure 4).

4

Management of adnexal masses during pregnancy. When a pregnant patient is symptomatic, due to torsion, pelvic pain or mass effect, surgery can be performed at any gestational age. In asymptomatic patients with incidental findings, management is guided by ultrasound morphology of the lesion. In these cases, if surgery is indicated, the optimal timing is between 12 and 18 weeks of gestation.

Most ovarian cysts detected during pregnancy are benign and asymptomatic, often resolving spontaneously without intervention. The risk of symptomatic complications correlates with cyst size, as larger lesions are more prone to torsion or rupture.7 Ovarian torsion is a particular concern: displacement of the ovaries by the enlarging uterus increases the risk of adnexal twisting.32 The incidence decreases after 20 weeks, likely due to reduced adnexal mobility as pregnancy advances.7,33

For the majority of asymptomatic adnexal masses, ultrasound plays a pivotal role in the preoperative discrimination between benign and malignant masses. To date, no diagnostic models, including those of IOTA (e.g. 'benign descriptors', ADNEX, two-step strategy), have been validated in a pregnant population. Similarly, the tumor biomarker CA 125 has limited utility in pregnancy: serum levels may be physiologically elevated, and increased values are also observed in several benign gynecologic conditions, including endometriosis.

At present, expert subjective assessment remains the cornerstone for distinguishing between benign and malignant adnexal masses. Testa et al.27 proposed a management algorithm that balances maternal–fetal safety with oncologic appropriateness (Table 2). According to this algorithm, symptomatic patients should undergo surgery at any gestational age, whereas the management of asymptomatic patients depends on the sonographic morphology of the adnexal mass and gestational age.

Sonographic evaluation should be performed using transvaginal ultrasound, supplemented by transabdominal ultrasound when necessary, with a standardized technique and reporting according to IOTA terminology. Counseling of pregnant patients is recommended at the end of the first trimester to assess the indication for elective surgery, ideally between 12 and 18 weeks of gestation. Management decisions should be guided by the sonographic morphology of the adnexal mass and individualized risk assessment, as follows:

- Unilocular cyst < 10 cm: surveillance is recommended.

- Unilocular cyst ≥ 10 cm or multilocular cyst: either surveillance or surgery may be considered, based on individual risk factors and shared decision-making, given the overall low risk of torsion and malignancy.

- Unilocular solid mass: requires individualized counseling, as either surveillance or surgery may be appropriate. The potential for borderline (≈30%) or invasive (≈7%) histology warrants careful assessment of additional features:

- Prior history of a unilocular cyst with ground-glass echogenicity, suggestive of a pre-existing endometrioma with decidualization-related changes during pregnancy.

- Presence and morphology of papillary projections at the first-trimester scan (regular vs. irregular surface, vascularization, number, size and shadowing). If multiple papillary projections are detected at the first-trimester scan, a borderline ovarian tumor should be considered. In particular, unilocular solid cysts with irregular papillary projections identified early in pregnancy and showing no morphological changes during the first half of gestation are more likely to represent borderline tumors.

- Interval changes: increase in the size or number of papillary projections during pregnancy raises the suspicion of invasive histology and should prompt surgical exploration. Conversely, in patients managed expectantly, a follow-up scan after 32 weeks can provide further information: reduction in cyst size supports decidualization, stability suggests benign or borderline disease, while enlargement strengthens the suspicion of invasive histology

- Multilocular solid or solid masses: surgical management should be considered, as it is associated with high malignancy risk (≈70%).

2

Algorithm for the management of adnexal masses during pregnancy based on sonographic morphology.27

| Sonographic morphology | Risk profile | Management |

| Unilocular cyst < 10 cm | Very low risk of torsion or malignancy | Surveillance |

| Unilocular cyst ≥ 10 cm or multilocular cyst | Low risk of torsion and malignancy; risk increases with size | Surveillance or surgery depending on risk factors and shared decision-making |

| Unilocular solid mass | Borderline histology ≈30%; invasive ≈7% | Requires individualized counseling. Consider history of endometrioma, papillary features and interval changes. If expectant: ≥ 32-week scan (regression → decidualization; stability → benign/borderline; enlargement → invasive suspicion) |

| Multilocular-solid mass; solid mass | High risk of malignancy | Surgical management generally indicated |

The management algorithm proposed by Testa et al. was derived from a retrospective analysis of 113 pregnant women who underwent sonographic examination at a tertiary referral oncology center over a 20-year period. They reported no malignancy in unilocular cysts, whereas malignancy was significantly more frequent in multilocular solid and solid masses.27 Their study also demonstrated that expectant management in selected cases does not compromise outcomes, as none of the patients undergoing surveillance showed morphological changes at 6 months postpartum.27 These findings support a risk-adapted approach in which masses with benign sonographic characteristics are monitored with serial ultrasound, while those with suspicious features are referred for surgical assessment. When surgery is indicated, laparoscopy is generally preferred over laparotomy, given its advantages in terms of faster postoperative recovery, reduced analgesic requirements and lower risk of thromboembolic events.7,34,35

Within this framework, the management of borderline ovarian tumors deserves special consideration. Moro et al. suggested that surgery could often be deferred until postpartum or performed concurrently with cesarean section, thereby minimizing intraoperative risks while ensuring timely oncologic evaluation.28 Given the relatively low incidence of malignancy in pregnancy and the potential fetal risks associated with surgical intervention, expectant management remains the preferred approach for adnexal masses that appear benign on ultrasound, with close monitoring to promptly identify cases requiring intervention.27

CONCLUSION

Most ovarian masses encountered during pregnancy are benign and tend to resolve spontaneously. Ultrasound represents the diagnostic modality of choice and the cornerstone of evaluation, although no pregnancy-specific validated scoring system is currently available. A conservative approach is generally recommended, while surgical management should be considered only in the presence of strong suspicion of malignancy or in cases complicated by acute events such as torsion, rupture or hemorrhage.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- Ultrasound is the first-line imaging modality for evaluating adnexal masses in pregnancy due to its safety, availability and high diagnostic accuracy.

- Serum CA 125 levels should not be used as a primary diagnostic tool in pregnancy due to physiologically elevated levels in the first trimester and their limited specificity for malignancy.

- The IOTA Simple Rules, ADNEX model and other scoring systems require further validation in pregnancy before reliable application. In this context, expert subjective assessment remains the mainstay of sonographic evaluation.

- Expectant management is preferred for simple ovarian cysts, as most resolve spontaneously without intervention. Masses with benign sonographic features (e.g. unilocular, anechoic, thin-walled) should be monitored with serial ultrasound, as the risk of malignancy is low.

- Ultrasonographic assessment of papillary projections should consider surface morphology: smooth and regular papillae with ground-glass echogenicity are more consistent with decidualized endometriomas, whereas irregular papillae with microcystic changes and anechoic or low-level echogenic fluid are more suggestive of borderline ovarian tumors.

- The presence, morphology and evolution of papillary projections should be assessed, as their number, surface regularity, vascularization and interval changes represent key features for differentiating between benign decidualized endometriomas and borderline or invasive ovarian tumors in pregnancy.

- Surgical intervention should be reserved for cases of suspected malignancy based on imaging or for symptomatic patients.

- When surgery is indicated, it is best performed in the second trimester to minimize maternal and fetal risks. Laparoscopy is preferred over laparotomy, except in cases in which the mass is large or malignancy is suspected.

- Ovarian cancer in pregnancy is rare but should be suspected in masses with solid or multilocular-solid morphology.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) of this chapter declare that they have no interests that conflict with the contents of the chapter.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

REFERENCES

Goh WA, Rincon M, Bohrer J, Tolosa JE, Sohaey R, Riaño R, Davis J, Zalud I. Persistent ovarian masses and pregnancy outcomes. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013 Jul;26(11):1090–3. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2013.768980. Epub 2013 Feb 21. PMID: 23356452. | |

Sherard GB, Hodson CA, Williams HJ, Semer DA, Hadi HA, Tait DL. Adnexal masses and pregnancy: a 12-year experience. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003 Aug;189(2):358–62. doi:10.1067/S0002-9378(03)00731-2 | |

Cathcart AM, Nezhat FR, Emerson J, Pejovic T, Nezhat CH, Nezhat CR. Adnexal masses during pregnancy: diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2023 Jun;228(6):601–612. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2022.11.1291. | |

de Haan J, Verheecke M, Van Calsteren K, Van Calster B, Shmakov RG, Mhallem Gziri M, Halaska MJ, Fruscio R, Lok CAR, Boere IA, Zola P, Ottevanger PB, de Groot CJM, Peccatori FA, Dahl Steffensen K, Cardonick EH, Polushkina E, Rob L, Ceppi L, Sukhikh GT, Han SN, Amant F; International Network on Cancer and Infertility Pregnancy (INCIP). Oncological management and obstetric and neonatal outcomes for women diagnosed with cancer during pregnancy: a 20-year international cohort study of 1170 patients. Lancet Oncol. 2018 Mar;19(3):337–346. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30059-7. Epub 2018 Jan 26. Erratum in: Lancet Oncol. 2021 Sep;22(9):e389. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00475-7 | |

Froyman W, Landolfo C, De Cock B, Wynants L, Sladkevicius P, Testa AC, Van Holsbeke C, Domali E, Fruscio R, Epstein E, Dos Santos Bernardo MJ, Franchi D, Kudla MJ, Chiappa V, Alcazar JL, Leone FPG, Buonomo F, Hochberg L, Coccia ME, Guerriero S, Deo N, Jokubkiene L, Kaijser J, Coosemans A, Vergote I, Verbakel JY, Bourne T, Van Calster B, Valentin L, Timmerman D. Risk of complications in patients with conservatively managed ovarian tumours (IOTA5): a 2-year interim analysis of a multicentre, prospective, cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2019 Mar;20(3):448–458. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30837-4. | |

Yazbek J, Salim R, Woelfer B, Aslam N, Lee CT, Jurkovic D. The value of ultrasound visualization of the ovaries during the routine 11–14 weeks nuchal translucency scan. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2007 Jun;132(2):154–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2006.07.013. | |

Mukhopadhyay A, Shinde A, Naik R. Ovarian cysts and cancer in pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2016 May;33:58–72. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2015.10.015. | |

Hoo WL, Yazbek J, Holland T, Mavrelos D, Tong EN, Jurkovic D. Expectant management of ultrasonically diagnosed ovarian dermoid cysts: is it possible to predict outcome? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Aug;36(2):235–40. doi: 10.1002/uog.7610. | |

Caspi B, Appelman Z, Rabinerson D, Zalel Y, Tulandi T, Shoham Z. The growth pattern of ovarian dermoid cysts: a prospective study in premenopausal and postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 1997 Sep;68(3):501–5. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(97)00228-8. | |

Caspi B, Levi R, Appelman Z, Rabinerson D, Goldman G, Hagay Z. Conservative management of ovarian cystic teratoma during pregnancy and labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000 Mar;182(3):503–5. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.103768. | |

Felemban AA, Rashidi ZA, Almatrafi MH, Alsahabi JA. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia and ovarian dermoid cysts in pregnancy. Saudi Med J. 2019 Apr;40(4):397–400. doi: 10.15537/smj.2019.4.24107. | |

Casarcia N, Coyne SA, Rawiji H. Anti-N-Methyl-D-Aspartate (NMDA) Receptor Encephalitis Secondary to an Ovarian Dermoid Cyst. Cureus. 2024 Aug 19;16(8):e67193. doi: 10.7759/cureus.67193. | |

Bansal M, Mehta A, Sarma AK, Niu S, Silaghi DA, Khanna AK, Vallabhajosyula S. Anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis in pregnancy associated with teratoma. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2023 Apr 28;36(4):524–527. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2023.2205814. | |

Akazawa M, Onjo S. Malignant Transformation of Mature Cystic Teratoma: Is Squamous Cell Carcinoma Different From the Other Types of Neoplasm? Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2018 Nov;28(9):1650–1656. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000001375. | |

Ayhan A, Aksu T, Develioglu O, Tuncer ZS, Ayhan A. Complications and bilaterality of mature ovarian teratomas (clinicopathological evaluation of 286 cases). Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1991 Feb;31(1):83–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828x.1991.tb02773.x. | |

Condous G, Khalid A, Okaro E, Bourne T. Should we be examining the ovaries in pregnancy? Prevalence and natural history of adnexal pathology detected at first-trimester sonography. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004 Jul;24(1):62–6. doi: 10.1002/uog.1083. | |

Hoover K, Jenkins TR. Evaluation and management of adnexal mass in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Aug;205(2):97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.01.050. | |

Van Holsbeke C, Van Calster B, Guerriero S, Savelli L, Paladini D, Lissoni AA, Czekierdowski A, Fischerova D, Zhang J, Mestdagh G, Testa AC, Bourne T, Valentin L, Timmerman D. Endometriomas: their ultrasound characteristics. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Jun;35(6):730–40. doi: 10.1002/uog.7668. | |

Pateman K, Moro F, Mavrelos D, Foo X, Hoo WL, Jurkovic D. Natural history of ovarian endometrioma in pregnancy. BMC Womens Health. 2014 Oct 15;14:128. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-14-128. | |

Ueda Y, Enomoto T, Miyatake T, Fujita M, Yamamoto R, Kanagawa T, Shimizu H, Kimura T. A retrospective analysis of ovarian endometriosis during pregnancy. Fertil Steril. 2010 Jun;94(1):78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.02.092. | |

Mascilini F, Savelli L, Scifo MC, Exacoustos C, Timor-Tritsch IE, De Blasis I, Moruzzi MC, Pasciuto T, Scambia G, Valentin L, Testa AC. Ovarian masses with papillary projections diagnosed and removed during pregnancy: ultrasound features and histological diagnosis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Jul;50(1):116–123. doi: 10.1002/uog.17216. | |

Doglioli M, De Meis L, Mantovani E, Cristani G, Seracchioli R, Del Forno S. Endometrioma decidualization in pregnancy: not just about papillations. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2025 May;65(5):657–658. doi: 10.1002/uog.29203. | |

Morice P. Borderline tumours of the ovary and fertility. Eur J Cancer. 2006 Jan;42(2):149–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.07.029 | |

Timor-Tritsch IE, Foley CE, Brandon C, Yoon E, Ciaffarrano J, Monteagudo A, Mittal K, Boyd L. New sonographic marker of borderline ovarian tumor: microcystic pattern of papillae and solid components. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Sep;54(3):395–402. doi: 10.1002/uog.20283. | |

Poder L, Coakley FV, Rabban JT, Goldstein RB, Aziz S, Chen LM. Decidualized endometrioma during pregnancy: recognizing an imaging mimic of ovarian malignancy. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2008 Jul-Aug;32(4):555–8. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e31814685ca. | |

Uccella S, Rosa M, Biletta E, Tinelli R, Zorzato PC, Botto-Poala C, Lanzo G, Gallina D, Franchi MP, Manzoni P. The Case of a Serous Borderline Ovarian Tumor in a 15-Year Old Pregnant Adolescent: Sonographic Characteristics and Surgical Management. Am J Perinatol. 2020 Sep;37(S 02):S61-S65. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1714080. | |

Testa AC, Mascilini F, Quagliozzi L, Moro F, Bolomini G, Mirandola MT, Moruzzi MC, Scambia G, Fagotti A. Management of ovarian masses in pregnancy: patient selection for interventional treatment. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2021 Jun;31(6):899–906. doi: 10.1136/ijgc-2020-001996. | |

Moro F, Mascilini F, Pasciuto T, Leombroni M, Li Destri M, De Blasis I, Garofalo S, Scambia G, Testa AC. Ultrasound features and clinical outcome of patients with malignant ovarian masses diagnosed during pregnancy: experience of a gynecological oncology ultrasound center. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2019 Sep;29(7):1182–1194. doi: 10.1136/ijgc-2019-000373. | |

Korenaga TK, Tewari KS. Gynecologic cancer in pregnancy. Gynecol Oncol. 2020 Jun;157(3):799–809. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2020.03.015. | |

Amant F, Berveiller P, Boere IA, Cardonick E, Fruscio R, Fumagalli M, Halaska MJ, Hasenburg A, Johansson ALV, Lambertini M, Lok CAR, Maggen C, Morice P, Peccatori F, Poortmans P, Van Calsteren K, Vandenbroucke T, van Gerwen M, van den Heuvel-Eibrink M, Zagouri F, Zapardiel I. Gynecologic cancers in pregnancy: guidelines based on a third international consensus meeting. Ann Oncol. 2019 Oct 1;30(10):1601–1612. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz228. | |

Leiserowitz GS, Xing G, Cress R, Brahmbhatt B, Dalrymple JL, Smith LH. Adnexal masses in pregnancy: how often are they malignant? Gynecol Oncol. 2006 May;101(2):315–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.10.022. | |

Hasson J, Tsafrir Z, Azem F, Bar-On S, Almog B, Mashiach R, Seidman D, Lessing JB, Grisaru D. Comparison of adnexal torsion between pregnant and nonpregnant women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Jun;202(6):536.e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.11.028. | |

Ginath S, Shalev A, Keidar R, Kerner R, Condrea A, Golan A, Sagiv R. Differences between adnexal torsion in pregnant and nonpregnant women. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2012 Nov-Dec;19(6):708–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2012.07.007. | |

Balinskaite V, Bottle A, Sodhi V, Rivers A, Bennett PR, Brett SJ, Aylin P. The Risk of Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes Following Nonobstetric Surgery During Pregnancy: Estimates From a Retrospective Cohort Study of 6.5 Million Pregnancies. Ann Surg. 2017 Aug;266(2):260–266. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001976. | |

Soriano D, Yefet Y, Seidman DS, Goldenberg M, Mashiach S, Oelsner G. Laparoscopy versus laparotomy in the management of adnexal masses during pregnancy. Fertil Steril. 1999 May;71(5):955–60. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(99)00064-3. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards program CLICK HERE)