This chapter should be cited as follows:

Sibal M, Gundabattula SR, Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.419713

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Gynecology Module

Volume 10

Ultrasound in gynecology

Volume Editors:

Professor Antonia Testa, Agostino Gemelli University Hospital, Rome, Italy

Professor Simona Maria Fragomeni, Agostino Gemelli University Hospital, Rome, Italy

Chapter

Ultrasound Diagnosis of Adnexal Torsion

First published: December 2025

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

Torsion is defined as the twisting of a bodily organ or part on its own axis.1 Torsion of an ovary refers to twisting of the ovary on its ligamentous supports causing compromised blood flow to the ovary. Often the Fallopian tube twists along with the ovary and this is referred to as adnexal torsion. Other adnexal structures, such as a paraovarian or paratubal cysts, may also undergo torsion.

Adnexal torsion is noted in about 2–3% of women presenting with acute pelvic pain.2,3 In a 10-year review, ovarian torsion accounted for 2.7% of emergency surgeries in women and was the fifth most common diagnosis following ectopic pregnancy, ruptured corpus luteal cyst, pelvic inflammatory disease and appendicitis.4 Ovarian hyperstimulation may be complicated by torsion in 8–12% of cases.5 Adnexal torsion is most common in women of reproductive age group but no age is exempt.

Adnexal torsion involves the tube and ovary in about 67% of cases.3 Isolated tubal torsion is less common and seen typically when the Fallopian tube is dilated (hydrosalpinx). Prompt diagnosis is important to preserve the function of the ovary and/or Fallopian tube. However, this can be challenging at times as symptoms are non-specific leading to diagnostic delay.

RISK FACTORS AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The presence of a benign ovarian lesion is the single greatest risk factor for adnexal torsion (Table 1) with dermoid cyst and serous cystadenoma being the most commonly found pathologies. Corpus luteal cysts account for most cases of torsion in the first trimester of pregnancy.

Ovarian torsion | Tubal torsion |

|

|

Torsion is more common on the right side probably because of the presence of the sigmoid colon on the left and the longer utero-ovarian ligament on the right.2,5,6 Ovaries fixed in the pelvis are less likely to tort as seen in endometrioma, tubo-ovarian abscess and malignancy. In postmenopausal women, ovarian torsion is uncommon; however, when it does occur, the rate of malignancy may be as high as 3–20%, compared with an overall malignancy rate of less than 3% in torsed ovaries.2,7,8

As the ovary twists on its ligamentous supports, its vascular supply becomes compromised. The severity of the vascular impairment depends on the number of twists, the tightness of the twists and duration since the twist. This can result in partial or complete vascular obstruction, which some refer to as partial or complete torsion, respectively. Following the twist, the lymphatic and venous channels are compromised first, because they have thinner walls and are more compressible. This causes vascular congestion and results in stromal edema. With ongoing torsion, this edema compromises arterial flow in the arterioles and capillaries resulting in ischemia, hemorrhage and necrosis.2 As a result, the torsed ovaries often appear enlarged and bluish-black at surgery.

CLINICAL FEATURES AND NATURAL HISTORY

Most patients with adnexal torsion are symptomatic. Asymptomatic presentation might signal either necrotic adnexa or non-compromised twisted ovary. The common symptoms and signs include:2,3,5

- Acute pelvic pain (44–97%)

- Nausea and vomiting (47–70%)

- Fever (2–20%)

- Abdominal tenderness (70%)

- Palpable mass (20–47%)

- Rebound tenderness (adnexal necrosis)

The pain is unilateral and is often triggered by exercise or a sudden movement that alters intra-abdominal pressure, such as straining during bowel movements, lifting heavy objects or performing yoga. It may radiate to the flank or back and can be constant or intermittent.

The potential adverse outcomes of a missed diagnosis include:5

- Autoamputation/atrophy over time of the ovary

- Pelvic adhesions

- Persistent pelvic pain with repeat hospital visits

- Tubal infertility (if the remaining ovary is functional)

- Hemorrhage and peritonitis

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of torsion is primarily based on clinical suspicion supported by sonographic findings. However, symptoms are non-specific and ultrasound examination is key to early diagnosis. Unfortunately, ultrasound is considered to have limited specificity and sensitivity of 79% and 76%, respectively;9 and laparoscopy is still commonly resorted to for diagnosis, when ultrasound findings or imaging are negative or inconclusive.

For ultrasound evaluation in clinically suspected torsion, a transabdominal scan is performed first, followed by a transvaginal scan. Most of the sonographic features of torsion described below are best visualized on transvaginal or transrectal scans. However, the transabdominal approach can be useful for identifying structures such as a twisted pedicle, as the full bladder displaces non-pelvic structures superiorly, providing a panoramic and unobstructed view of the pelvic anatomy.

Commonly seen non-specific ultrasound findings

- Enlarged ovary – torsion is more common in ovaries that are enlarged with a functional cyst, a benign neoplastic mass or hyperstimulation. Congestion and edema of the ovarian stroma secondary to torsion also contribute to the increased size.

- Hemorrhagic cysts – hemorrhage within the cyst could be because of a physiological hemorrhagic corpus luteal cyst or due to hemorrhage into the cyst secondary to torsion.

- Abnormal position – the torsed ovary may be displaced from its usual position and, consequently, its location may not correlate with the reported site of pain. It may be seen on the opposite side, anterior to the uterus or impacted in the pouch of Douglas.

- Free fluid – this is frequently seen in women of reproductive age even in the absence of torsion. In cases of torsion, free fluid is almost always present. Therefore, the absence of free fluid should prompt reconsideration of the diagnosis, as it may not be a case of torsion.

- Tenderness – the torsed organs are frequently tender to touch but probe tenderness may not be evident after analgesic administration.

Specific ultrasound findings

- Twisted ovarian pedicle with the whirlpool sign – the twisted pedicle appears as an extraovarian heterogeneous mass which is elongated and tubular on long section and appears as a circumscribed mass on transverse section. It appears hyperechoic with multiple concentric hypoechoic stripes or shows hypoechoic beads within (engorged vessels) and often has a bright echogenic center, appearing as the ‘target sign’.

The whirlpool sign is a spiral pattern produced when the probe is moved gently along the long axis of the pedicle on grayscale and Doppler. In order to elicit the sign, a heterogeneous mass around the organ suspected to have torsed should be looked for, followed by rotation of the probe to visualize the cross-section of the pedicle, i.e. ‘target sign’, and then angulation along the pedicle to elicit the whirlpool sign and possibly count the number of twists.

The pedicle can mimic other pelvic structures such as the Fallopian tubes and intestinal loops but the whirlpool sign of the twisted pedicle is a very specific feature of ovarian torsion. - Follicular ring sign – this is the presence of prominent thick (1–2 mm) hyperechoic margins of antral follicles in the torsed ovary. It results from increased hydrostatic pressure of the capillaries around the antral follicles following obstruction of venous flow with continuing arterial flow and leads to edema and hemorrhage in the follicular walls. This is an early feature of torsion, which is easy to detect, the only prerequisite being the visualization of antral follicles. As torsion progresses, the edema and hemorrhage spread to the rest of the ovarian stroma, making the follicular ring sign less distinct.

- Ovarian stromal edema – this is typically seen as bulky afollicular stroma with or without peripherally displaced follicles. The stroma appears heterogeneous and hyperechoic due to congestion and hemorrhage. It may appear as a solid mass on transabdominal scan where the peripheral antral follicles may not be well seen. It has reduced utility when ovarian tissue is minimal or not seen and is not a feature of non-ovarian torsion. Sometimes, afollicular ovarian tissue is misconstrued as edema.

- Absent Doppler flow – in early torsion, blood flow may be normal followed by loss of venous and then arterial flow. Absent flow is a late feature and difficult to assess when tissue is limited as in a torsed paraovarian cyst or hydrosalpinx. Normal Doppler flow does not exclude the diagnosis of torsion.

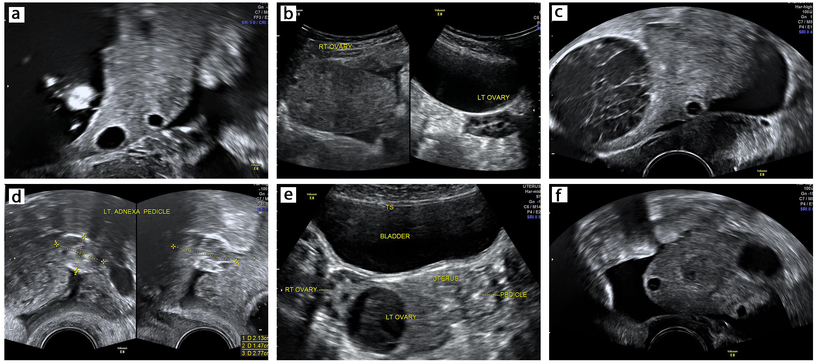

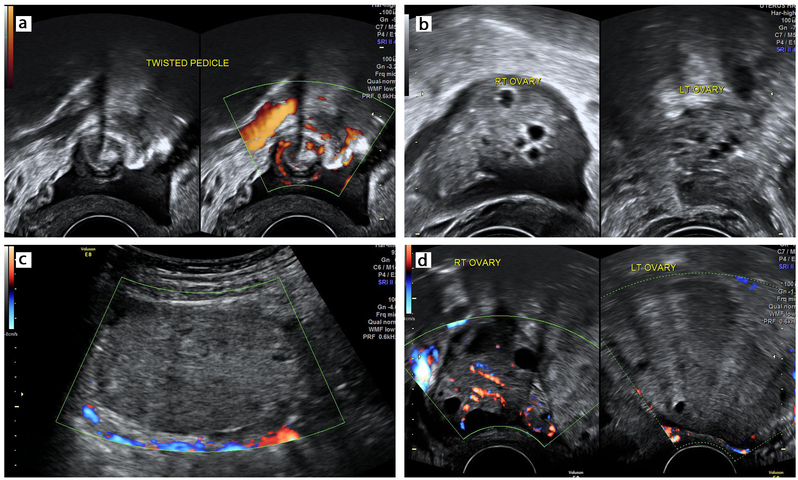

The ultrasound findings of adnexal torsion are summarized in Table 2 and depicted in Figures 1 and 2. An enlarged ovary, hemorrhagic cysts, abnormal position, free fluid and tenderness are commonly seen. The specific findings which can be used in diagnosis are: ovarian stromal edema, whirlpool sign of the twisted pedicle, absent Doppler flow and the follicular ring sign. The contralateral non-torsed ovary provides a convenient control to elicit the sonographic findings.

Ultrasound feature | Advantage | Limitation |

Enlarged ovary can be the cause or effect of torsion |

|

|

Hemorrhagic cyst: cysts if present are typically hemorrhagic and thick walled |

|

|

Abnormal position: unusual location of the ovary such as contralateral, anterior to uterus or in pouch of Douglas |

| |

Free fluid: small amount of fluid usually seen |

| |

Probe tenderness: torsed organs typically tender |

| |

Twisted pedicle: extraovarian heterogeneous mass showing the ‘target sign’ |

| |

Whirlpool sign (91%): spiral pattern produced when the probe is moved gently along the long axis of the pedicle on grayscale and Doppler |

|

|

Follicular ring sign (49%): prominent 1–2 mm thick hyperechoic margins of antral follicles due to perifollicular edema and hemorrhage |

|

|

Ovarian edema (79%): seen as bulky afollicular stroma with or without peripherally displaced follicles; may appear as a solid mass on transabdominal scan |

|

|

Absent Doppler flow (52%): following a twist, first venous and then arterial flow is lost; in early torsion, flow may be normal |

|

|

1

Non-specific ultrasound findings of ovarian torsion: (a) enlarged ovary secondary to a dermoid cyst; (b) enlarged right ovary as a result of torsion-induced edema with normal left ovary; (c) hemorrhagic cyst; (d) extraovarian pedicle; (e) torsed left ovary displaced to the right side; (f) free fluid.

2

Specific ultrasound findings of ovarian torsion: (a) twisted pedicle with whirlpool sign; (b) follicular ring sign in right ovary and normal antral follicles in left ovary; (c) ovarian stromal edema; (d) absent Doppler flow in torsed left ovary with normal flow in right ovary.

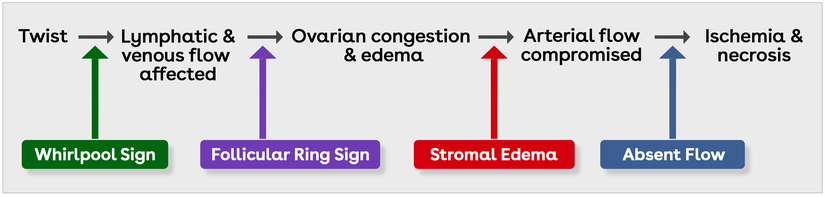

Of the four specific features of torsion, the whirlpool sign is present from the onset in all types of adnexal torsion. As lymphatic and venous flow become compromised, the follicular ring sign is seen as an early feature of ovarian congestion. Ovarian stromal edema with or without peripherally displaced follicles is seen later as ovarian congestion and edema progress. Absent flow is a late feature of torsion when arterial flow is compromised resulting in ischemia and necrosis. This is depicted in Figure 3 and Videoclip 1.

3

Timeline of events in adnexal torsion.

1

Specific ultrasound findings of ovarian torsion in order of appearance.

Special situations

Torsion with necrosis and gangrene

When torsion with necrosis and gangrene occur, symptoms may paradoxically lessen. On ultrasound, there is often complete loss of normal ovarian architecture with markedly heterogeneous ovarian tissue. No flow is typically seen on Doppler. In some cases, the shape of the ovary may change transiently with probe pressure, and gelatinous necrotic tissue may demonstrate a characteristic 'jiggling' motion when intermittent pressure is applied.

Torsion of the Fallopian tube

Usually, the tube torts along with the ovary, and is visualized as a thickened segment of the Fallopian tube close to the twisted pedicle. This is typically difficult to identify on ultrasound particularly because the tube does not have any specific feature to help identify it.

Torsion of a hydrosalpinx can occur in isolation and is usually identified by the whirlpool sign. Other sonographic features of torsion that may be seen are thickened walls, turbid hemorrhagic intraluminal fluid and absent flow within the walls (though this can be difficult to assess). The dilated tube is often located medial to a normal ipsilateral ovary, tapering at either end in a configuration known as the 'beak' sign.2,14

Torsion of paraovarian cyst

Paraovarian and paratubal cysts may also undergo torsion, which is usually isolated but may involve the ovary or Fallopian tube. Diagnosis of paraovarian cyst torsion is made using the whirlpool sign. Other features that may be seen are thickened walls, turbid intraluminal fluid and absence of flow in the cyst walls (difficult to assess). If the ovary is not involved, the antral follicles on that side do not show the follicular ring sign.

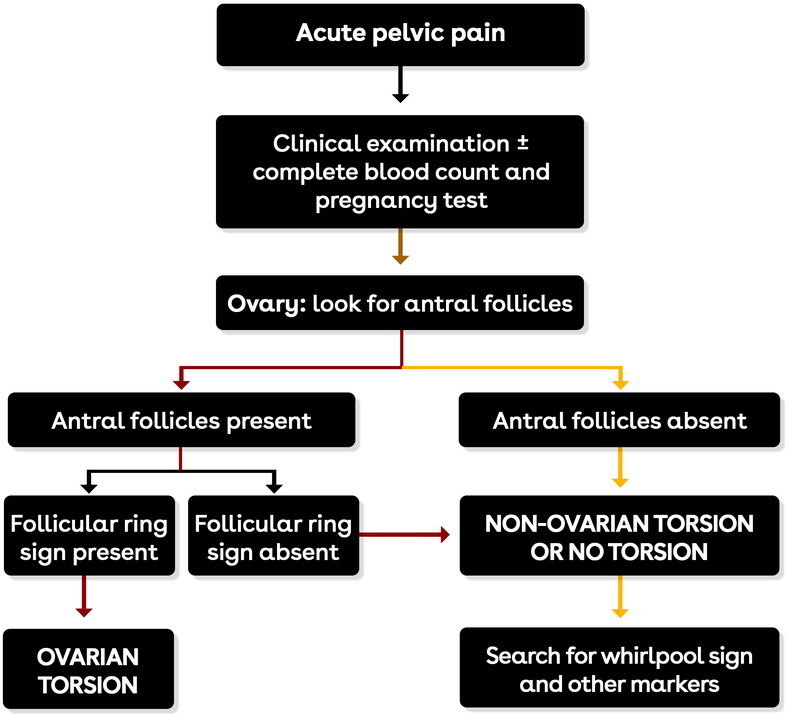

Figure 4 presents a simple flowchart for the sonographic assessment of torsion. In a pilot study conducted in our center (unpubl. data), follicular ring sign was seen in 50 of 74 (68%) cases of confirmed ovarian torsion while, in the remainder, the antral follicles could not be visualized.

4

Simple flow diagram of ultrasound diagnosis of adnexal torsion.

Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging

In women with acute pelvic pain, ultrasound is the initial imaging modality of choice, especially if gynecological etiology is suspected. Imaging with computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be helpful if ultrasound is inconclusive in centers with limited expertise. The accuracy of CT scan for torsion is as low as 42% because the pedicle twist can be difficult to visualize on CT images. MRI is often unavailable in the acute setting and is primarily used in atypical cases to clarify equivocal findings seen with other modalities, aid anatomic localization and/or characterize lead masses if there is a concern for malignancy.2,5,15

Definitive preoperative confirmation of torsion is vital because a false-negative report can lead to loss of tubo-ovarian function while a false-positive diagnosis can result in complications from a surgical exploration, particularly in pregnant women or those with endometriosis or previous abdominal surgery.16

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The clinical differential diagnosis of adnexal torsion includes all major causes of acute pelvic pain (Table 3).

Clinical differential | Ultrasound differential |

Pregnancy-related

Adnexal pathology

Uterine cause

Non-gynecological cause

| Enlarged ovary

Ovarian displacement

Ovarian edema

Peripherally placed follicles

Extraovarian pedicle

|

MANAGEMENT

Fear of thromboembolic complications and the misconception that bluish-black discoloration signified irreversible gangrene were unfounded myths that historically led to unnecessary oophorectomies. In current practice, once torsion is diagnosed, laparoscopic detorsion is the mainstay of treatment.2,5,17

Although some suggest that irreversible ovarian damage occurs if there is a delay in detorsion of ≥ 72 hours, the appearance of the ovary at surgery is not a reliable indicator of ovarian viability, and preservation of function has been reported in > 90% of cases after detorsion. Therefore, a torsed ovary must not be removed unless a severely necrotic ovary falls apart or there is a suspicion of malignancy or the woman is postmenopausal.

Conservative management of torsion via transabdominal or transvaginal ultrasound-guided cyst aspiration is an alternative in patients with simple anechoic cysts with anesthesia-related risks or with physiological cysts such as in pregnancy.18 Drainage of the cyst fluid may reduce the pressure in the adnexa and lead to spontaneous detorsion, failing which surgical management is recommended.

Postoperative follow-up

An ultrasound examination may be performed 4–6 weeks after the untwisting procedure, to document the preservation of the ovarian parenchyma, by assessing ovarian size, vascularization and follicular development, particularly in patients with no flow on Doppler.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- Ultrasound is the imaging modality of choice for making a diagnosis in clinically suspected adnexal torsion.

- Clinical symptoms are non-specific, the most common being unilateral acute pelvic pain, which may be intermittent.

- Non-specific ultrasound features that are commonly seen include enlarged ovary, hemorrhagic cysts, abnormal position of the ovary and free fluid.

- The specific ultrasound features of torsion are as follows:

- Whirlpool sign of the twisted pedicle is a useful sign, which can be seen from the outset in both ovarian and non-ovarian torsion. However, eliciting this sign requires considerable expertise.

- Follicular ring sign is a simple, early and specific feature of ovarian torsion, its limitation being lack of utility in non-ovarian torsion and ovarian torsion in which antral follicles cannot be visualized.

- Edematous ovarian stroma with or without peripherally placed follicles is a late feature and is of limited use when ovarian tissue is not visualized or is minimal.

- Absence of Doppler flow is a late feature and the presence of flow does not rule out torsion. Another pitfall associated with this feature is the possibility of a false-positive diagnosis if Doppler settings are not appropriate.

- Management of torsion is by prompt surgical intervention (laparoscopy) to confirm the diagnosis, untwisting the torsed organ and excision of any lesion, if safe and feasible. The ovary should be left in situ even if it appears dusky unless the patient is postmenopausal, the mass is necrotic and friable or there is a concern of malignancy.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) of this chapter declare that they have no interests that conflict with the contents of the chapter.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

REFERENCES

Merriam-Webster dictionary. Definition of torsion. Merriam-Webster website. Available from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/torsion. Accessed October 14, 2025. | |

Dawood MT, Naik M, Bharwani N, Sudderuddin SA, Rockall AG, Stewart VR. Adnexal torsion: review of radiologic appearances. Radiographics 2021;41:609–624. doi: 10.1148/rg.2021200118. | |

Strachowski LM, Choi HH, Shum DJ, Horrow MM. Pearls and pitfalls in imaging of pelvic adnexal torsion: seven tips to tell it's twisted. Radiographics 2021;41(2):625–640. doi: 10.1148/rg.2021200122. | |

Hibbard LT. Adnexal torsion. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;152(4):456–461. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(85)80157-5. | |

Laufer MR. Ovarian and fallopian tube torsion. In: UpToDate, Sharp HT and Chakrabarti A, editors. Wolters Kluwer, August 6, 2025. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/ovarian-and-fallopian-tube-torsion. Accessed September 9, 2025. | |

Boyd CA, Riall TS. Unexpected gynecologic findings during abdominal surgery. Curr Probl Surg 2012; 49(4): 195–251. | |

Cohen A, Solomon N, Almog B, Cohen Y, Tsafrir Z, Rimon E, Levin I. Adnexal torsion in postmenopausal women: clinical presentation and risk of ovarian malignancy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24(1):94–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2016.09.019. | |

Eitan R, Galoyan N, Zuckerman B, Shaya M, Shen O, Beller U. The risk of malignancy in post-menopausal women presenting with adnexal torsion. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;106(1):211–214. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.03.023. | |

Wattar B, Rimmer M, Rogozinska E, Macmillian M, Khan KS, Al Wattar BH. Accuracy of imaging modalities for adnexal torsion: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG 2021;128(1):37–44. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16371. | |

Sibal M. Follicular ring sign: a simple sonographic sign for early diagnosis of ovarian torsion. J Ultrasound Med. 2012;31(11):1803–1809. doi: 10.7863/jum.2012.31.11.1803. | |

Vijayaraghavan SB. Sonographic whirlpool sign in ovarian torsion. J Ultrasound Med. 2004;23(12):1643–9; quiz 1650–1. doi: 10.7863/jum.2004.23.12.1643. | |

Moro F, Bolomini G, Sibal M, Vijayaraghavan SB, Venkatesh P, Nardelli F, Pasciuto T, Mascilini F, Pozzati F, Leone FPG, Josefsson H, Epstein E, Guerriero S, Scambia G, Valentin L, Testa AC. Imaging in gynecological disease (20): clinical and ultrasound characteristics of adnexal torsion. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2020;56(6):934–943. doi: 10.1002/uog.21981. | |

Garde I, Paredes C, Ventura L, Pascual MA, Ajossa S, Guerriero S, Vara J, Linares M, Alcázar JL. Diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound signs for detecting adnexal torsion: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2023;61(3):310–324. doi: 10.1002/uog.24976. | |

Gross M, Blumstein SL, Chow LC. Isolated fallopian tube torsion: a rare twist on a common theme. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185(6):1590–1592. doi: 10.2214/AJR.04.1646. | |

Rey-Bellet Gasser C, Gehri M, Joseph JM, Pauchard JY. Is it ovarian torsion? A systematic literature review and evaluation of prediction signs. Pediatr Emerg Care 2016;32(4):256–261. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000621. | |

Valsky DV, Cohen SM, Hamani Y, Lipschuetz M, Yagel S, Esh-Broder E. Whirlpool sign in the diagnosis of adnexal torsion with atypical clinical presentation. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009;34(2):239–242. doi: 10.1002/uog.7310. | |

Kives S, Gascon S, Dubuc E, Van Eyk N. SOGC Clinical Practice Guideline No. 341 – Diagnosis and management of adnexal torsion in children, adolescents and adults. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2017;39(2):82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2016.10.001. | |

Berg L, Eagles N, Kastora S, Farren J, Naftalin J, Jurkovic D. Ultrasound-guided cyst aspiration for management of acute adnexal torsion. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2025;65(6):790–797. doi: 10.1002/uog.29225. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards program CLICK HERE)