This chapter should be cited as follows:

Steben M, Kjetland EF, et al., Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.419983

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Gynecology Module

Volume 12

Infections in gynecology

Volume Editors:

Professor Francesco De Seta, Department of Medical, Surgical and Health Sciences, Institute for Maternal and Child Health, University of Trieste, IRCCS Burlo Garofolo, Trieste, Italy

Dr Pedro Vieira Baptista, Lower Genital Tract Unit, Centro Hospitalar de São João and Department of Gynecology-Obstetrics and Pediatrics, Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade do Porto, Portugal

Chapter

Female Genital Schistosomiasis

First published: August 2023

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

Female genital schistosomiasis (FGS) affects 56 million girls and women in Sub-Saharan Africa1 and many believe that the burden is greatly underestimated.2 The WHO classifies FGS in the neglected tropical disease group.3 It is one of the many manifestations of a parasitic worm called schistosomiasis. The most common agent responsible for the urogenital form of this disease is Schistosoma haematobium. People are infected when the free-swimming larval stage (cercariae) released in fresh water from snails penetrate the skin where they become schistosomula and migrate through the tissues to mature into adults in the venous plexuses around the urinary bladder.3 FGS is underdiagnosed but has severe implications for women’s reproductive health.1

PHYSIOPATHOLOGY

After exposure to infected water, larval flukes burrow into the skin, where the immature larvae take 4–6 weeks to mature into adult worms in the urinary bladder’s network of veins.4 Adult female worms start to shed eggs as early as 4 weeks after infection. These eggs travel through the blood vessels to the pelvic and urinary organs, where some are trapped in the tissue linings, and some are shed into urine, semen, or the vagina and cervix.3

SYMPTOMS

Of those girls and women who are infected, 75% have lesions in the uterus, cervix, vagina, or vulva. The symptoms come from the inflammation and lesions caused by the infestation of the urinary and/or genital tracts by the motile schistosomes and the eggs they lay.5 The most common symptoms in female are vaginal discharge that can be purulent and/or bloody, bleeding, or spotting with or without intercourse, genital itching, genital burning, pelvic and/or coital pain.6,7,8 Some women may present with urinary incontinence. As the syndromic approach to genital discharge proposed by the WHO does not list FGS as a potential cause, this disease usually goes untreated but the women and very frequently their partners are treated as having a sexually transmitted infection (STI).9 Some women may even be treated as if they have cancer.10,11 In some areas endemic for schistosomiasis, FGS may be the most common cause of genital lesions.12 Another aspect to take into consideration is that FGS can affect transgender people with vaginas, uteruses, and/or cervixes.

COMPLICATIONS

The genital lesions and inflammation contribute to pregnancy issues such as infertility, spontaneous abortion, or ectopic pregnancy.13,14 They also increase the sexual transmission or acquisition of HIV by up to 4 times.12,15,16

Both the symptoms and complications of FGS in women can affect their mental health and social status, and infertility, spontaneous abortion, and presentation of symptoms like those of STIs may be taboo in many cultures and lead to stigmatization and social exclusion.17,18

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

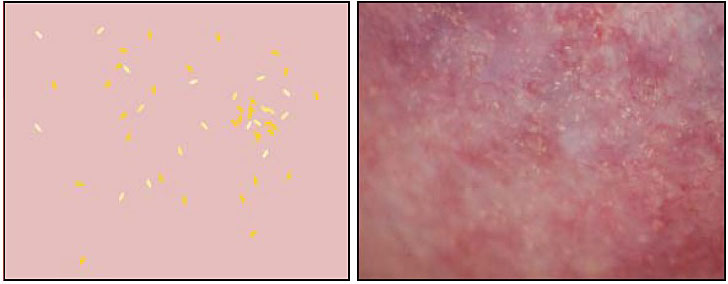

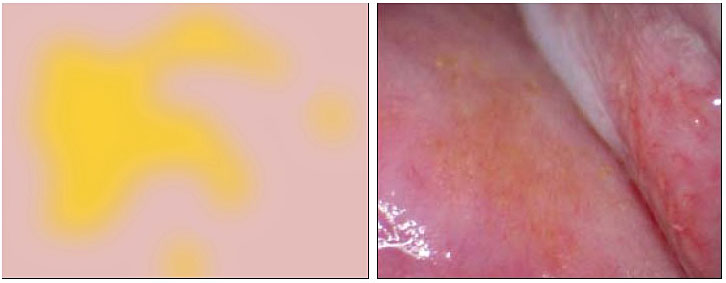

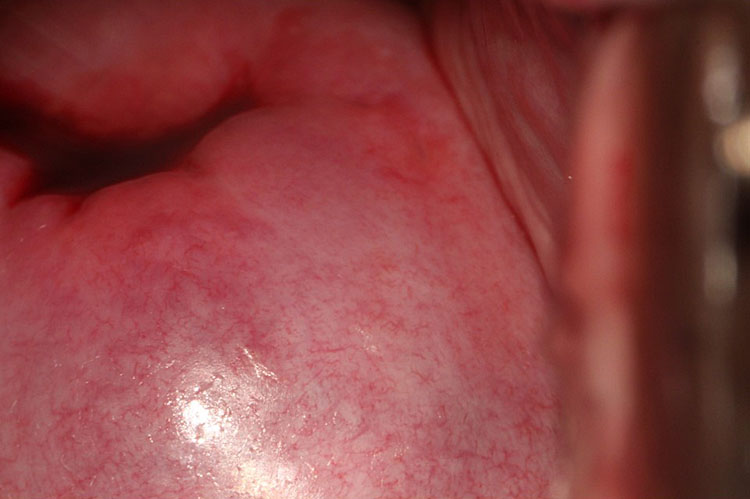

Upon speculum examination, one may see discharge of various colors, bleeding or oozing from lesions, yellowish lesions, and vaginal swelling. Best seen with a magnifying device such as a colposcope, at least one of three vaginal and/or cervical findings, may be adequate for diagnosis for FGS:19 (1) sandy patches appearing as single or clustered grains (Figure 1), (2) homogeneous yellow areas (Figure 2); or (3) rubbery yellowish papules (Figure 3).20,21,22 Frequently, abnormal blood vessels and contact bleeding are also seen (Figure 4). Some lesions may resemble those of cancer. The WHO FGS pocket atlas and a clinical poster are freely available for improving recognition and surveillance of FGS (http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/180863/1/9789241509299_eng.pdf).3

|

|

1

This image is from the cervix. Sandy patches in bladder/vagina will look very different (more "corrugated" surface). Reproduced with permission. Owner Eyrun F Kjetland.

|

|

2

Vaginal homogeneous yellow patches. Reproduced with permission. Owner Eyrun F Kjetland.

|

|

3

Rubbery papules (Madagascar). Reproduced with permission. Owner Eyrun F Kjetland.

|

|

4

Vaginal abnormal blood vessels. Reproduced with permission. Owner Eyrun F Kjetland.

DIAGNOSIS

Urogenital schistosomiasis is diagnosed through the detection of their eggs in urine specimens.23,24 Antibodies and/or antigens detected in blood or urine samples are also indications. A urine sample is collected between 10:00 and 14:00 to ensure optimal schistosome egg yield. Merthiolate-formalin solution (2%) is added to 10 ml of urine for preservation, if microscopy cannot be done immediately. Urine samples are then centrifuged and the whole pellet is deposited on one or more glass slides. Schistosome ova in the whole pellet urine are counted by microscopy.

For urinary schistosomiasis, a filtration technique is the standard diagnostic technique.25 However, many with genital schistosomiasis have negative urines.11,26 Children with urinary schistosomiasis almost always have microscopic blood in their urine detectable by urinary strips. However, this is not a good technique for women of reproductive age.27

For people living in non-endemic or low-transmission areas, serological and immunological tests may be useful in showing exposure to infection and the need for thorough examination, treatment, and follow-up.28,29,30,31

Best seen with a magnifying device such as a colposcope, at least one of three vaginal and/or cervical findings, as mentioned in the previous section, may be adequate for the diagnosis of FGS.

The differential diagnosis for FGS includes cervical cancer and STIs. Urogenital schistosomiasis is endemic in Africa. In accordance with the WHO recommendations, most countries have adopted a syndromic patient management system, which facilitates treatment without a laboratory confirmation of the diseases.9 Hence, women who come to health services with abnormal genital discharge, cancer-looking lesions, dyspareunia, or infertility most likely will not be treated for schistosomiasis but for STIs or cervical cancer.

The Pap test is not useful in FGS diagnosis.

TREATMENT

Pre-emptive treatment of children with praziquantel can be delivered in large-scale schools or community-based preventive programs and is very cost-effective.

Early and late lesions should be identified to provide the right treatment. The only study evaluating the effect of praziquantel on clinical manifestations showed that chronic genital lesions are not reversed over the course of 2 years.32 Another study has shown that Schistosoma DNA was detectable in genital specimens for 6 months following treatment.33

Groups targeted for treatment are as follows:

- School-age children (6–15 years of age) in endemic areas.

- Adults (>15 years) considered to be at risk in endemic areas from special groups: pregnant and lactating women and groups with occupations involving contact with infested water, such as fishermen, farmers, irrigation workers, or women whose domestic tasks bring them into contact with infested water.

- Entire communities living in highly endemic areas.

Praziquantel dosage for children is a single 30–60 mg/kg dose. For adults including pregnant and lactating women, a single 30–60 mg/kg dose is also recommended and should be taken with a meal. Using the dose pole to estimate the number of tablets, instead of scales, it was shown in a study showed that 98.3% of adults would receive adequate or optimal dosage of the drug.34

POTENTIAL DRUG INTERACTIONS

Concomitant use of rifampicin, frequently used for tuberculosis treatment, should be avoided. Rifampicin should be discontinued 4 weeks before administration of praziquantel.35 Rifampicin can be restarted 1 day after praziquantel treatment. Concomitant administration of drugs that increase the activity of drug metabolizing liver enzymes (cytochrome P450), such as antiepileptic drugs (i.e., phenytoin, phenobarbital, and carbamazepine), or dexamethasone may reduce plasma levels of praziquantel and their concomitant use is not recommended. Concomitant administration of drugs that decrease the activity of cytochrome P450 (i.e., cimetidine, ketoconazole, itraconazole, or erythromycin) may increase the plasma levels of praziquantel. Chloroquine, when taken simultaneously, may lead to lower blood concentrations of praziquantel in blood. The mechanism of this drug–drug interaction is unclear. The most frequently reported adverse reactions (>1/10) are headache, dizziness, fatigue, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and urticaria.

PREVENTION AND CONTROL

The control of schistosomiasis is based on large-scale treatment of at-risk population groups, access to safe water, improved sanitation, hygiene education and behavior change, and snail control and environmental management.36,37

The new report on ending the neglect to attain the sustainable development goals: neglected tropical diseases road map 2021–2030, adopted by the World Health Assembly, set as global goals the elimination of schistosomiasis as a public health problem in all endemic countries and the interruption of its transmission (absence of infection in humans) in selected countries.37,38,39

CONCLUSIONS

FGS elimination, as proposed by the WHO, would be a great leap toward the achievement of sustainable development goal 3 of good health and well-being, sustainable development goal 5 of gender equality, and sustainable development goal 10 of reducing inequality. In recent years, with a huge number of displaced women, immigrants or refugees, many of them from the Sub-Sahara region, have been observed, who may have unanswered cases of HIV, genital pain or discharge, bleeding, or infertility. Prevention and treatment of FGS is an issue of social justice, sexual and reproductive health and human rights.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- You may not know the condition but most likely you have seen cases.

- FGS is a differential diagnosis for cervical cancer and sexually transmitted infections.

- Diagnosis should be considered in migrant women, refugees, travelers to endemic countries as well as in women with infertility, vaginal discharge, and vaginal or cervical lesions.

- For people living in non-endemic or low-transmission areas, serological and immunological tests may be useful in showing exposure to infection and the need for a thorough examination, treatment, and follow-up.

- The only study evaluating the effect of praziquantel on clinical manifestations showed that chronic genital lesions are not reversed over the course of 2 years.

ILLUSTRATIONS

Eyrun F Kjetland is the owner of the pictures. Permission for taking the pictures and their use for education purposes was obtained from women.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) of this chapter declare that they have no interests that conflict with the contents of the chapter.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

REFERENCES

UNAIDS, World Health Organization. No more neglect. Female genital schistosomiasis and HIV. Integrating reproductive health interventions to improve women’s lives. Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. Available: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/female_genital_schistosomiasis_and_hiv_en.pdf. | |

Williams CR, Seunik M, Meier BM. Human rights as a framework for eliminating female genital schistosomiasis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2022;16. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0010165. | |

Mbabazi PS, Vwalika B, Randrianasolo BS, et al. World Health Organisation Female genital schistosomiasis. A pocket atlas for clinical health-care professionals. WHO/HTM/NTD/2015.4. Geneva: WHO, 2015. Available: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/180863/1/9789241509299_eng.pdf. | |

Colley DG, Bustinduy AL, Secor WE, et al. Human schistosomiasis. Lancet 2014;383:2253–64. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61949–2. | |

Feldmeier H, Poggensee G, Krantz I. A synoptic inventory of needs for research on women and tropical parasitic diseases. II. Gender-related biases in the diagnosis and morbidity assessment of schistosomiasis in women. Acta Trop 1993;55:139–69. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7903838. | |

Kjetland EF, Kurewa EN, Ndhlovu PD, et al. Female genital schistosomiasis – a differential diagnosis to sexually transmitted disease: Genital itch and vaginal discharge as indicators of genital S. haematobium morbidity in a cross-sectional study in endemic rural Zimbabwe. Trop Med Int Heal 2008;13:1509–17. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02161.x. | |

Hegertun IEA, Sulheim Gundersen KM, Kleppa E, et al. S. haematobium as a Common Cause of Genital Morbidity in Girls: A Cross-sectional Study of Children in South Africa. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2013;7:e2104(1–8). doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002104. | |

Galappaththi-Arachchige HN, Hegertun IEA, Holmen S, et al. Association of urogenital symptoms with history of water contact in young women in areas endemic for S. haematobium. a cross-sectional study in rural South Africa. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2016;13:1–12. doi:10.3390/ijerph13111135. | |

WHO. Guidelines for the management of symptomatic sexually transmitted infections. Guidelines for the management of symptomatic sexually transmitted infections. 2021:216. Available: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240024168. | |

Randrianasolo BS, Jourdan PM, Ravoniarimbinina P, et al. Gynecological manifestations, histopathological findings, and schistosoma-specific polymerase chain reaction results among women with schistosoma haematobium infection: A cross-sectional study in Madagascar. J Infect Dis 2015;212:1–11. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiv035. | |

Kjetland EF, Gwanzura F, Ndhlovu PD, et al. Simple clinical manifestations of genital Schistosoma haematobium infection in rural Zimbabwean women. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2005;72:311–9. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15772328. | |

Kjetland EF, Hegertun IEA, Baay MFD, et al. Genital schistosomiasis and its unacknowledged role on HIV transmission in the STD intervention studies. Int J STD AIDS 2014;25:705–15. doi:10.1177/0956462414523743. | |

Miller-Fellows SC, Howard L, Kramer R, et al. Cross-sectional interview study of fertility, pregnancy, and urogenital schistosomiasis in coastal Kenya: Documented treatment in childhood is associated with reduced odds of subfertility among adult women. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2017;11. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0006101. | |

Kjetland EF, Kurewa EN, Mduluza T, et al. The first community-based report on the effect of genital Schistosoma haematobium infection on female fertility. Fertil Steril 2010;94:1551–3. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.12.050. | |

Colombe S, Machemba R, Mtenga B, et al. Impact of schistosome infection on long-term HIV/AIDS outcomes. In: Slyker JA, (ed.) PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2018;12:e0006613. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0006613. | |

Kjetland EF, Ndhlovu PD, Gomo E, et al. Association between genital schistosomiasis and HIV in rural Zimbabwean women. AIDS 2006;20:593–600. doi:10.1097/01.aids.0000210614.45212.0a. | |

Gyapong M, Marfo B, Theobold S, et al. The double jeopardy of having female genital schistosomiasis in poorly informed and resourced health systems in Ghana. Trop Med Int Heal 2015;20:7. Available: http://www.embase.com/search/results?subaction=viewrecord&from=export&id=L72054219%5Cnhttp://dx.doi.org/10.1111/tmi.12575%5Cnhttp://sfx.hul.harvard.edu/sfx_local?sid=EMBASE&issn=13602276&id=doi:10.1111%2Ftmi.12575&atitle=The+double+jeopardy+of+having+fema. | |

Jacobson J, Pantelias A, Williamson M, et al. Addressing a silent and neglected scourge in sexual and reproductive health in Sub-Saharan Africa by development of training competencies to improve prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of female genital schistosomiasis (FGS) for health workers. Reprod Health 2022;19:1–15. doi:10.1186/s12978-021-01252-2. | |

Kjetland EF, Norseth HM, Taylor M, et al. Classification of the lesions observed in female genital schistosomiasis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2014;127:227–8. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2014.07.014. | |

Holmen SD, Kleppa E, Lillebø K, et al. The first step toward diagnosing female genital schistosomiasis by computer image analysis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2015;93:80–6. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.15-0071. | |

Holmen S, Galappaththi-Arachchige HN, Kleppa E, et al. Characteristics of blood vessels in Female Genital Schistosomiasis: Paving the way for objective diagnostics at the point of care. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2016;10:1–16. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0004628. | |

Norseth HM, Ndhlovu PD, Kleppa E, et al. The colposcopic atlas of schistosomiasis in the lower female genital tract based on studies in Malawi, Zimbabwe, Madagascar and South Africa. PLoS Neglected Trop Dis 2014;8:e3229(1–17). doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0003229. | |

Galappaththi-Arachchige HN, Holmen S, Koukounari A, et al. Evaluating diagnostic indicators of urogenital Schistosoma haematobium infection in young women: A cross sectional study in rural South Africa. PLoS One 2018;13:1–15. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0191459. | |

Nemungadi TG, Kleppa E, van Dam GJ, et al. Female Genital Schistosomiasis Lesions Explored Using Circulating Anodic Antigen as an Indicator for Live Schistosoma Worms. Front Trop Dis 2022;3:821463. doi:10.3389/fitd.2022.821463. | |

Hatz CF, Vennervald BJ, Nkulila T, et al. Evolution of Schistosoma haematobium-related pathology over 24 months after treatment with praziquantel among school children in southeastern Tanzania. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1998;59:775–81. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9840596. | |

Poggensee G, Kiwelu I, Saria M, et al. Schistosomiasis of the lower reproductive tract without egg excretion in urine. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1998;59:782–3. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/htbin-post/Entrez/query?db=m&form=6&dopt=r&uid=0009840597. | |

Gundersen SG, Kjetland EF, Poggensee G, et al. Urine reagent strips for diagnosis of schistosomiasis haematobium in women of fertile age. Acta Trop 1996;62:281–7. doi:10.1016/S0001-706X(96)00029-0. | |

Brunet J, Pfaff AW, Hansmann Y, et al. An unusual case of hematuria in a French family returning from Corsica. Int J Infect Dis 2015;31:59–60. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2014.10.024. | |

Pérignon A, Pelicot M, Consigny PH, et al. Genital schistosomiasis in a traveler coming back from Mali. J Travel Med 2007;14:197–9. doi:10.1111/j.1708-8305.2007.00124.x. | |

Bialek R, Knobloch J. Schistosomiasis in German children. Eur J Pediatr 2000;159:530–4. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=10923230. | |

Roure S, Pérez-Quílez O, Vallès X, et al. Schistosomiasis Among Female Migrants in Non-endemic Countries: Neglected Among the Neglected? A Pilot Study. Front Public Heal 2022;10:425. doi:10.3389/FPUBH.2022.778110/BIBTEX. | |

Kjetland EF, Mduluza T, Ndhlovu PD, et al. Genital schistosomiasis in women: a clinical 12-month in vivo study following treatment with praziquantel. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2006;100:740–52. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16406034. | |

Downs JA, Kabangila R, Verweij JJ, et al. Detectable urogenital schistosome DNA and cervical abnormalities 6 months after single-dose praziquantel in women with Schistosoma haematobium infection. Trop Med Int Heal 2013;18:1090–6. doi:10.1111/tmi.12154. | |

Palha De Sousa CA, Brigham T, Chasekwa B, et al. Dosing of Praziquantel by Height in Sub-Saharan African Adults. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2014;90:634–7. doi:10.4269/AJTMH.13-0252. | |

World Health Organization. Praziquantel Tablets 600 mg Macleods Pharmaceuticals, 1–9. Available: http://omr.bayer.ca/omr/online/biltricide-pm-en.pdf. | |

World Health Organization. Helminth control in school-age children: A guide for managers of control programmes, 2011. | |

World Health Organization (WHO) Schistosomiasis. In: WHO [Internet] 2023 [cited 4 Feb 2023]. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/schistosomiasis#:~:text=The WHO strategy for schistosomiasis,of all at-risk groups. | |

Nemungadi TG, Furumele TE, Gugerty MK, et al. Establishing and Integrating a Female Genital Schistosomiasis Control Programme into the Existing Health Care System. Trop Med Infect Dis 2022;7:382. doi:10.3390/TROPICALMED7110382. | |

World Health Organization. WHO guideline on control and elimination of human schistosomiasis, 2022. Available: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240041608?msclkid=66e125e4aa9911eca97802b2699b0852. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards programme CLICK HERE)