This chapter should be cited as follows:

Fazari ABE, AbdAlla M, et al, Glob. libr. women's med.,

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.415823

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Obstetrics Module

Volume 12

Operative obstetrics

Volume Editor: Professor Owen Montgomery, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, USA

Chapter

Operative Obstetrical Care of Women who are Victims of FGM

First published: October 2022

Study Assessment Option

By completing 4 multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development awards from FIGO plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM

See end of chapter for details

INTRODUCTION

Female genital mutilation (FGM) or female circumcision (FC) describes practices that manipulate, alter or remove the external genital organs in young girls and women1 for non-medical reasons. Although pervasive around the world in 30 countries, this practice is common in Africa and the Middle East. UNICEF estimates that 200 million girls and women alive today are infibulated and more than 3 million girls in Africa alone are at risk of undergoing FGM annually.2 Outside Africa, FGM is also practiced in Yemen, Iraq, Kurdistan and parts of Indonesia and Malaysia. Far smaller numbers have been recorded in India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, the United Arab Emirates, Oman, Peru and Colombia.

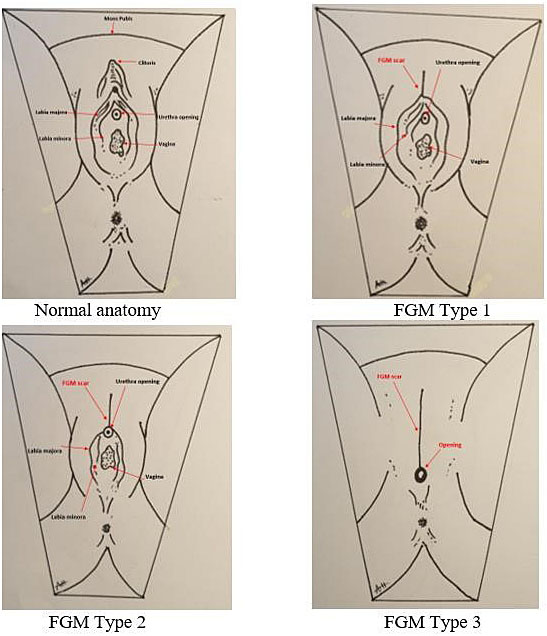

The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies female genital mutilation into four major types (Figure 1): type 1, removal of the prepuce and/or clitoris; type 2, removal of clitoris and labia minora; type 3, also known as infibulation, the vaginal opening is altered to create a smaller orifice, with or without the removal of the external genitalia; and type 4, includes all other harmful procedures to the female genitalia for non-medical purposes, i.e., pricking, pulling, piercing, scraping and cauterization.2

1

Female genital mutilation classification accreted by the World Health Organization.

Type | Description |

Type 1 | Partial or total removal of the clitoris and/or the prepuce (clitoridectomy). |

Type 2 | Partial or total removal of the clitoris and the labia minora, with or without excision of the labia majora (excision). |

Type 3 | Narrowing of the vaginal orifice with creation of a covering seal by cutting and appositioning the labia minora and/or the labia majora, with or without excision of the clitoris (infibulation). |

Type 4 | All other harmful procedures to the female genitalia for non-medical purposes, for example, pricking, piercing, incising, scraping and cauterization. |

1

Diagrammatic representation of normal anatomy with different FGM types.

2

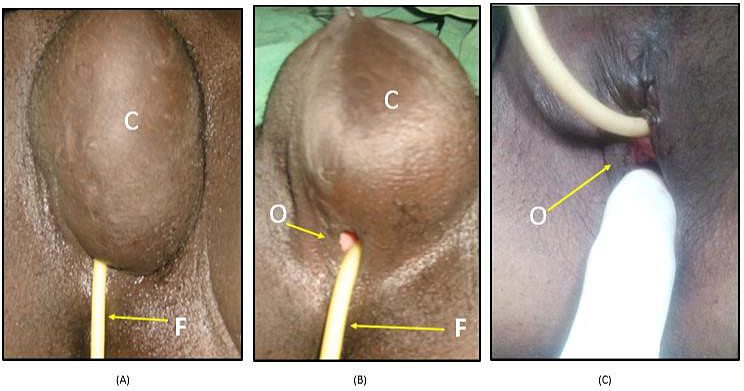

Typical FGM type 3; infibulation, the worst form of FGM.

The classification of FGM types may sometimes be complicated due to the following:

- The complete lack of anatomical knowledge of the female genitalia.

- The procedure is done at an age when the female organs are not fully developed and are smaller in size.

- Techniques used in the procedure are not surgically oriented.

- Lack of anesthetics.

- Psychological fear and post-traumatic stress factors from the use of physical force for the procedure.

- Post-FGM sequels of infection and healing process.

On occasion, FGM types present atypically, due to the lack of anatomical orientation and knowledge of the circumcisers. To illustrate, the vulvar excision is sometimes seen at one side and just sutured over the other side. At times, some of the excised labia majora remnants are sutured with the intact side labia minora. However, despite the mentioned factors, the typical shape of the scar persists and accordingly matches the classification of the FGM type, seen in Figures 3 and 4.

The issue of organ damage is not as precise as described in the WHO classification. The following are some examples:

- The clitoris and the labia minora are found intact under the excised and infibulated labia majora.

- The vulvar excision is sometimes seen at one side and just sutured over the other side.

- Some of excised labia majora remnants are sutured with intact side labia minora.

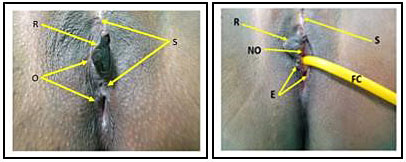

3

This FGM is difficult to classify, unfortunately many of the cases seen present as such. Image A (on the left) shows two scars (S) and two openings (O) with some remains of the vulval (R) seen in between, complete or partially, just after defibulation. Image B (image on the right) shows one opening (NO) with remnants of mainly the right labia minora (R) and a clear free urethral meatus fixed Folly catheter (FC) with a free healthy wound of the opening margin (E). The patient in this image only agreed to undergo defibulation and refused any further surgeries, thus the old high scar is still in place.

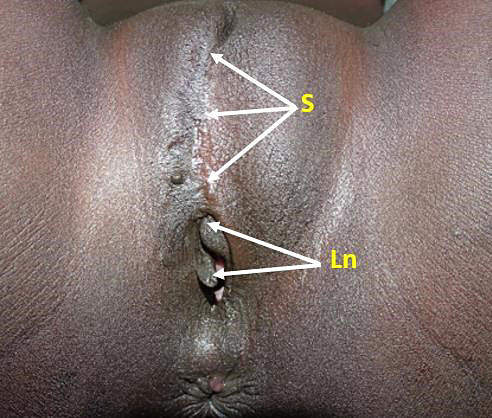

4

In this image, FGM 3 is presented, the labia minora is completely removed and has some keloid at the scar (S) in addition to some remains of the partially cut labia minora (Ln).

Mutilations are often performed by traditional circumcisers who have little to no medical training, without the use of any anesthetics or antiseptics. Some circumcisers have an exceptionally clean and sophisticated place for such a practice under the umbrella of religious extremism coverage. A girl is physically restrained, and a blade or glass is used for the incision and/or excision. This practice poses various adverse medical consequences, including direct complications from the procedure, hemorrhage during and after the procedure, infection and increased risk of death for young girls and their infants in subsequent pregnancies, post-traumatic stress disorders and urinary tract infections.3

The custom of female genital mutilation or female genital cutting has profound sociocultural roots in countries it is practiced in, making it the social norm for families to be accepted by their communities. Though no religious scripts suggest the practice of FGM, it is highly supported by cultural ideals of modesty and femininity and the notion that female genital mutilation improves hygiene. These protocols place pressures on parents to perform FGM to maintain and promote their daughters’ chastity, prevent promiscuity and prepare them for marriage. On average, FGM is carried out on young girls between infancy to adolescence and occasionally on adult women.2

SHORT-TERM AND LONG-TERM CONSEQUENCES OF FGM

Female genital mutilation can have short-term and long-term consequences, varying by the type and severity of cutting, the health condition of the girl being mutilated, the condition of the environment and the tools used for the procedure. Several short-term consequences include extreme pain, since this procedure is most often conducted without any anesthetics, difficulty in passing urine, hemorrhage, infections, fever, shock and damage to the genital organs. Dysmenorrhea and hematocolpos (accumulation of menstrual blood in the vagina) can be the result of the narrowing of the vaginal orifice. Furthermore, infections and incomplete healing of the wound post-mutilation may result in formation of abscesses, keloid scars and cysts on the vulva (Figure 5), which can be extremely painful and prevent sexual intercourse.4 Unfortunately, these complications are amplified as they carry out into the adulthood of these women. It is estimated that 1 in every 500 circumcisions results in death.5

5

The vulval-inclusion cyst is one of the most common long-term complications of FGM, which varies in shape and size (A). The only seen opening down to the cyst when Folly’s catheter is inserted before surgery (B), which was finished with some resort of the shape (C).

Sex is one of our innate biological drives in life. The interaction between biology and psychology results in these sexual behaviors. Victims of FGM are deprived from their right as human beings from sexual health and from enjoying any sexual pleasure; due to the removal of parts of the erogenous genital zones and sexually responsive vascular tissue.6 A meta-analysis presented by Berg and Denison showed that women subjected to FGM were more likely to report dyspareunia (relative risk (RR) = 1.52, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.15, 2.0), no sexual desire (RR = 2.15, 95% CI = 1.37, 3.36) and less sexual satisfaction (standardized mean difference = −0.34, 95% CI = −0.56, −0.13).7 Studies have used the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), a reliable 19-item questionnaire developed as an instrument to assess the key dimensions of sexual function in women. FSFI identifies five domains: desire and subjective arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction and pain/discomfort. A case–control study included 333 genitally cut women and 317 uncut women were requested to complete the Arabic Female Sexual Function Index (ArFSFI) and were then subjected to clinical examination where the cutting status was confirmed. The study reported significantly lower full-scale scores in women in the FMG/C group in all domain scores, except for sexual pain. The pain domain was significantly lower in the FGM/C group with comparison to uncut women.8 These results are parallel with Rouzi et al.'s cross-sectional study. In this study, 107 women completed the survey and the gynecological examination, which revealed that 39% of the women had FGM/C type 1, 25% had type 2 and 36% had type 3. The study documented a substantial proportion of women subjected to FGM/C experience sexual dysfunction. Additionally, the study confirmed a correlation between the anatomical extent of FGM/C being related to the severity of sexual dysfunction.9 Overall, these findings emphasize the magnitude of the effect of female genital mutilation in women’s sexuality. FGM victims are robbed of their fundamental sexual experiences.

Psychological and emotional trauma is the result of an unusual event that entirely shatters your sense of well-being. Girls, who undergo FGM, are victimized at an incredibly young age and experiencing trauma as a child can have severe long-lasting effect.

The World Health Organization reported that women living with female genital mutilation often experience psychological trauma immediately after the procedure, from the pain, shock and the use of physical force by those performing FGM.10 Additionally, as documented by Behrendt and Moritz the long-term effect seen in women with FGM, include post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, depression and memory loss.11

OBSTETRIC FGM COMPLICATIONS

FGM in pregnancy and childbirth

In pregnancy natural physiological changes occur in response to the growth of the fetus. These changes occur in response to many elements; increased total blood volume and blood supply to all the genital organs making the external genital organs more vascular as well as weight gain occurs throughout pregnancy as the fetal size increases. Childbirth is one of the most painful experiences in a woman’s life and female genital mutilation may leave a woman mentally and emotionally terrified of childbirth. Although reliable evidence on the effect of female genital mutilation and childbirth is limited, FGM is associated with higher risk of gynecological and obstetrical consequences on women’s health and neonates.12

The World Health Organization conducted a study examining the effect of different types of FGM on obstetric outcome. The findings of the study outlined that women with FGM have adverse obstetric outcomes and found a direct correlation between the risk of obstetric complications and the extent of FGM.13

Prolonged labor and/or obstruction during pregnancy are the most frequent obstetric outcomes of FGM in all types of FGM.10 Labor is frightening for women with FGM. Women with FGM type 3 who had already given birth, were interviewed and remembered being concerned about the size of the vaginal opening for childbirth and some even tried to limit fetal growth for an easier childbirth.14 Women of FGM are not at risk for obstetric complications alone, neonatal health is also compromised. An observational study found a significant increased risk of perinatal death with type 2 FGM. Additionally, the study found an increased risk for neonatal resuscitation in all forms of FGM.15 In a 2006 African study, at 28 obstetric centers in 6 countries, on 28393 women with FGM, found infants born from a mother with FGM were at increased risk of stillbirth and early neonatal death. Female genital mutilation is estimated to lead to an extra 1–2 perinatal deaths per 100 deliveries. The participants of this study showed mutilated women were at greater risk from cesarean section, perianal trauma and postpartum hemorrhage in comparison to women without FGM.16

Furthermore, women with type 3 mutilation had a 70% higher risk of postpartum hemorrhage ≥500 mL more, than women who were not mutilated. Additionally, 41% of uncut primipara required an episiotomy and 88% of primipara type 3 required episiotomy. Among women who had had previous deliveries, the proportions were 14% and 61%, respectively. A correlation between type of episiotomy and obstetric outcomes was investigated among 6187 women with type 3 FGM and found that mutilated women with type 3 required episiotomies to protect against anal sphincter tears and postpartum hemorrhage.17

Rectovaginal or vesicovaginal fistula is an abnormal opening in the vagina to the rectum or bladder, causing a continuous leakage of urine, feces or both. Globally, approximately one to two million women are living with fistula, majority residing in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. Severe forms of FGM (infibulation) may predispose women to fistula. Contextual and socioeconomic factors may increase the likelihood of fistula.18 A case report (Preston, 1937), described a case of birth per rectum causing a rectovaginal fistula and attributed it to the hard scar tissue of FGM type 3, which acted as an obstruction to vaginal delivery.19

FGM-related fistulas can cause physical, social and psychological traumas in women, which arises as a serious concern for public health.20

The objective of the Reconstructive Surgery for FGM (RCSFGM) package is to clinically assess each case under anesthesia to restore the anatomy to look and feel normal.

OPERATIVE CARE AND MANAGEMENT

The aims of RCSFGM are as follows:

- Facilitate comfortable anatomical passage for the physiology of the organs.

- Restore some of the destructed anatomy to improve the body image.

The surgery largely depends on the following:

- Remains of circumcised tissues.

- Skills and experience of the surgeon on how to make use of these remains.

Female genital mutilation poses great life-long complications to women. Few treatment options exist for victims of FGM. Nevertheless, today not all women who have undergone female genital mutilation have access to these surgical interventions available.

Defibulation is a surgical procedure to divide the scar tissue, which is narrowing the vaginal opening in FGM type 2 and mainly FGM type 3. This is recommended if the vaginal opening is not adequate to:

- pass urine normally;

- have sex comfortably;

- have an internal examination;

- have a cervical smear test;

- have vaginal surgery;

- have a safe vaginal delivery.

Defibulation must be carried out under adequate anesthesia for adequate pain relief, can be under local, spinal or general anesthetics and can be performed any time before marriage, during pregnancy or during childbirth. Defibulation is the release of the scarred infibulated tissues at the midline to expose the remaining structures if they are there, then urethral meatus, the vaginal opening and the edges on both sides are over sown with rapidly absorbable sutures. The purpose of this surgery is to restore the anatomy of the entrance as far as possible.

Antenatal defibulation should be offered and performed during the antenatal period, during the second trimester, typically around 20 weeks, which allows ample time for the scar to heal and reduces the risk of laceration during delivery.21 Women may choose to wait until childbirth to undergo defibulation, when it is culturally accepted or preferred. During labor, defibulation should be performed in the first stage of labor under epidural. If defibulation is left until the second stage of labor, an incision is made during the crowning of the fetal presenting part to expose the urethra, leaving the perineum intact.22

Most women who underwent defibulation saw an improvement in sexual function.23 In a study, 18 patients were asked to fill the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) before surgery and at 6 months follow-up. Female function improvement was seen in the domain's desire, arousal, satisfaction, and pain whereas, lubrication and orgasm remained unchanged.24 Researchers concluded that the majority (94%) of defibulated women and their husbands were both pleased with the results of defibulation.

Reinfibulation is the re-suturing of the incised tissue after delivery or gynecological procedures. Although prohibited by law, it is still practiced in communities where FGM is accepted as part of the culture (Figure 6).

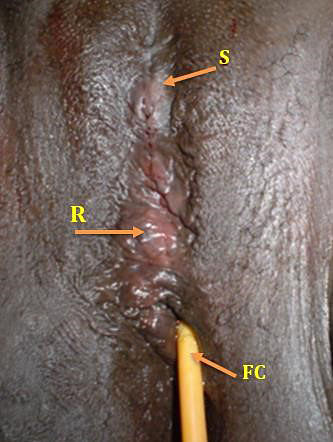

6

In this image, urine retention after reinfibulation; Folly’s catheter was fixed (FC). Reinfibulation procedure (R) and old scar of FGM (S).

Moreover, reconstructive surgery can be performed along with other surgical procedures, such as cyst or mass removal. A case report of a young woman with FGM type 3, with a large vulvar mass underwent excision of the mass and reconstructive surgery of the mutilated genital tissue.25 The mass was successfully removed, and the external genital organs were reconstructed. In an alternative prospective study in Sudan, 660 women with varying types of FGM underwent reconstructive surgery. The study documented 86% of the women were very satisfied post-operatively with the shape of the vulva, disappearance of discharge, the healing duration and regaining or starting sexual activity. This study confirmed that reconstructive surgery for female genital mutilation victims (RCSFGM) could be performed to restore some of the female external genital anatomy with a high degree of patients’ acceptance, satisfaction and potential improvement in female sexuality.25

A reconstructive surgery for FGM initiative in Sudan; one of the countries where FGM is deeply rooted in the community, started in early 2000 in collaboration with a national program. At the time, most of the African countries and their high political governmental bodies are committed to fight against FGM, with the assistance of external supporters/advocators, non-governmental, such as WHO, UNFPD, world bank and ZERO tolerance FGM. At a local level in Sudan, the Salima initiative “all girls are born intact, keep them intact” intends to resolve and prevent female genital mutilation. The initiative study was extended to more than 8000 cases of FGM patients for RCSFGM. Following the removal of the cyst, the surgeons made use of the skin remains to restore the vulval shape using the available skin, labia major or minora and expose the remain/clitoris body for more sexual pleasure and better physical appearance, to help the victims regain self-possession, ergo, almost all of the RCSFGM patients became health promotors against FGM with personal commitments to end the practice of FGM, starting in their families. This result was presented in consecutive updates in many regional and international conferences, in local university activities, women support ceremonies, at national and international levels, and so forth.

The success of this initiative is not only measured in these women’s behavioral changes and satisfaction but also in the training of devoted dictated specialists of OBSGYN who received sufficient background in counselling and psychological aspects of FGM victims in addition to the skillful surgical training under direct supervision. RCSFGM package services are complimentary provided by multidisciplinary team. The success of this program depends on many distinctive groups of people; both medical and non-medical, working together to facilitate the process of this initiative.

The RCSFGM package includes the following:

- Clinical assessment of the circumcised vulva and the depth of mutilation along with all comorbidity.

- Psychological assessment and counselling. Post-traumatic stress, embracement, abashment, frightfulness and sexuality as we see clients in different age groups and needs.

- Medications for treating in case of infections.

- Treatment and support for patients with HIV and/or hepatitis, as FGM procedures can take place as ceremonious events, many girls at the same time.

- Anticipation of the outcome in regard to the shape and the function of the sensitive part of women after surgery and how to accept the new look after correction.

- Health education and special training to act against FGM and to support the victims along with patient’s recruitment.

- Health education sessions for women’s health concern and reproductive health issues for RCSFGM promotion, antenatal care contraception, safe sex, post-abortion care, sexual transmitted infection and maternal morbidity/mortality.

Women with FGM type 1, do not need to undergo defibulation, since only the prepuce and/or clitoris was excised. Clitoral reconstruction surgery is a fairly new feasible and effective surgical technique26 introduced by Thabet and Thabet to reduce clitoral pain and improve sexual pleasure. Clitoral reconstruction surgery also called clitoral transposition, re-exposes healthy clitoral neo-glans by removal of the cutaneous and subcutaneous peri-clitoral scar tissue. Clitoral reconstruction surgery showed a positive outcome in pain reduction, improved sexual function and self-body image. Women with FGM type 2 and type 3 requested clitoral reconstruction surgery for chronic vulvar pain as well to enhance sexual response and to have a genital appearance like non-infibulated women.27 A study documented two women with FGM type 2 and type 3 who requested clitoral reconstruction. After 1-year post-operative, both women were satisfied with their results and felt happy and more beautiful. The woman reported no vulvar pain, improved sexual pleasure and orgasm. The second woman described improved sexuality, which was attributed to better body image.27 Though results appear promising, limited studies and publications are available on the clitoral reconstructive surgery; more evidence is necessary to develop guidelines to improve practices.

More systematic research is needed to determine the extent and scale of the health effects and morbidity associated with female genital mutilation. Essentially, female genital mutilation is a violation of human rights and reconstructive surgery needs to be made more available in developed countries by training health professionals at all levels. Defibulation pre-pregnancy is the objective for mutilated women. Female genital mutilation can be reduced and eradicated through public education, cultural empowerment of girls and by raising awareness of the harmful effects of FGM, to encourage change in the public opinions.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Author(s) statement awaited.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

REFERENCES

Female Genital Mutilation: Health Consequences and Complications – A Short Literature Review. Elliot Klein, 1 Elizabeth Helzner, 2 Michelle Shayowitz, 1 Stephan Kohlhoff, 1 and Tamar A. Smith-Norowitz. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6079349. | |

World Health Organization: Female genital mutilation, 2020. | |

Female Genital Mutilation and its Management RRR Green-top Guideline No. 53, 2015 | |

WHO. Female genital mutilation: an overview. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1995. | |

Reyners M. Health consequences of female genital mutilation. Reviews in Gynaecological Practice 2004;4(4):242–51. doi: 10.1016/j.rigp.2004.06.001. | |

Buggio L, Facchin F, Chiappa L, et al. Psychosexual Consequences of Female Genital Mutilation and the Impact of Reconstructive Surgery: A Narrative Review. Health Equity 2019;3(1):36–46. Published 2019 Feb 20. doi:10.1089/heq.2018.0036. | |

Berg RC, Denison E. Does Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (FGM/C) Affect Women’s Sexual Functioning? A Systematic Review of the Sexual Consequences of FGM/C. Sex Res Soc Policy 2012;9:41–56. | |

Alsibiani SA, Rouzi AA. Sexual function in women with female genital mutilation. Fertil Steril 2010;93:722–4. | |

Rouzi AA, Berg RC, Sahly N, et al. Effects of female genital mutilation/cutting on the sexual function of Sudanese women: a crosssectional study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;217:62..e1-e62.e6. | |

28 Too Many. (n.d.). Retrieved December 09, 2020, from https://www.28toomany.org/blog/the-psychological-effects-of-femalegenital-mutilation-research-blog-by-serene-chung/. | |

Behrendt A, Moritz S. Posttraumatic stress disorder and memory problems after female genital mutilation. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162(5):1000–2. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.5.1000. PMID: 15863806. | |

Frega A, Puzio G, Maniglio P, et al. Obstetric and neonatal outcomes of women with FGM I and II in San Camillo Hospital, Burkina Faso. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2013;288(3):513–9. doi: 10.1007/s00404-013-2779-y. Epub 2013 Mar 8. PMID: 23471548. | |

WHO study group on female genital mutilation and obstetric outcome. Female genital mutilation and obstetric outcome: WHO collaborative prospective study in six African countries. Lancet 2006;367:1835–41. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68805-3. | |

WHO. A Systematic Review of the Health Complications of Female Genital Mutilation Including Sequelae in Childbirth. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, 2000. | |

Armitage A, Bittaye M, Agbala S, et al. G261 Neonatal outcomes of female genital mutilation/cutting (fgm/c) in the gambia: results from a multicentre prospective observational study Archives of Disease in Childhood 2018;103:A107. | |

WHO study group on female genital mutilation and obstetric outcome, Banks E, Meirik O, Farley T, Akande O, Bathija H, Ali M. Female genital mutilation and obstetric outcome: WHO collaborative prospective study in six African countries. Lancet 2006;367(9525):1835–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68805-3. | |

Rodriguez MI, Seuc A, Say L, et al. Episiotomy and obstetric outcomes among women living with type 3 female genital mutilation: a secondary analyisis. Reprod Health 2016;13:131. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-016-0242-9. | |

Mathieu M-G, Véronique F, Sékou S, et al. Prevalence of symptoms of vaginal fistula in 19 subSaharan Africa countries: a meta-analysis of national household survey data. The Lancet Global Health 2015;3(5):e271e278. ISSN 2214-109. | |

Preston PG. “A case of birth per rectum”. The East African Medical Journal 1937;14:290–4. | |

Birge O, Ozbey E, Güzel, Ö, et al. The relationship between urogenital fistula and female genital mutilation. Journal of Turgut Ozal Medical Center 2016;23:293–6. | |

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Female Genital Mutilation. RCOG Statement No. 3. London: RCOG, 2003. | |

Review Obstetric management of women with female genital mutilation. https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1576/toag.9.2.095.27310. | |

Health Equity 2019;3(1):36–46. Published online 2019 Feb 20. doi: 10.1089/heq.2018.0036. | |

Krause E, Brandner S, Mueller MD, et al. Out of Eastern Africa: defibulation and sexual function in woman with female genital mutilation. J Sex Med 2011;8(5):1420–5. doi: 10.1111/j.17436109.2011.02225.x. Epub 2011 Mar 2. PMID: 21366880. | |

Fazari ABE, Berg RC, Mohammed WA, et al. Reconstructive surgery for female genital mutilation starts sexual functioning in Sudanese woman: A case report. J Sex Med 2013;10:2861–5. | |

Thabet SM, Thabet AS. Defective sexuality and female circumcision: the cause and the possible management. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2003;29(1):12–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1341-8076.2003.00065.x. PMID: 12696622. | |

Abdulcadir J, Rodriguez MI, Petignat P, et al. Clitoral reconstruction after female genital mutilation/cutting: case studies. J Sex Med 2015;12(1):274–81. doi:10.1111/jsm.12737. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can now automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development credits from FIGO plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering 4 multiple choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter.

Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about FIGO’s Continuing Professional Development awards programme CLICK HERE)