This chapter should be cited as follows:

Li JJ-X, Cheung AN-Y, Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.422023

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Gynecology Module

Volume 13

Gynecological cancer

Volume Editors:

Professor Hextan Ngan , Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Professor Karen Chan, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Chapter

HPV-Negative Cervical Cancer in the HPV-Vaccination Era: Pathology Perspective

First published: December 2025

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

High-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) is recognized as the most important carcinogenic factor for cervical cancer (Figure 1), accounting for the great majority of cases. In the current era of increasing HPV-vaccine coverage and the widespread use of HPV testing for cervical cancer prevention and screening, HPV-negative cervical cancer has gained attention because of its potential clinical implications. With the use of molecular diagnostic techniques, pathological characterization of HPV-independent cervical carcinomas has been advancing, and several biologically and morphologically distinct entities have been identified. In this chapter, updated clinicopathological and molecular characteristics of significant HPV-independent cervical carcinomas, as well as the challenges associated with cytology-based screening and pathological diagnosis, are described.

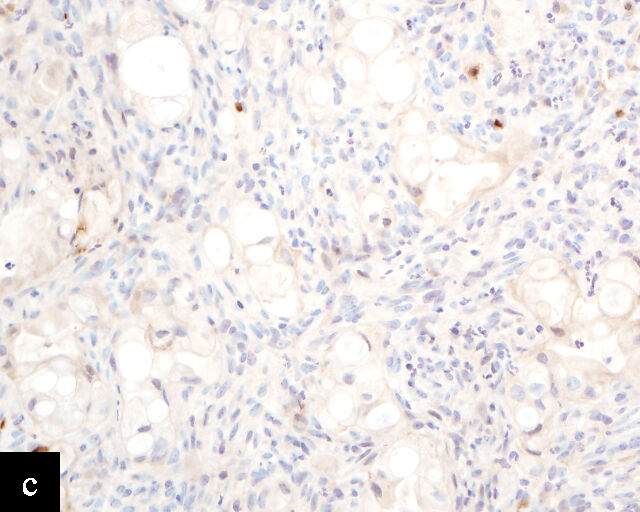

1

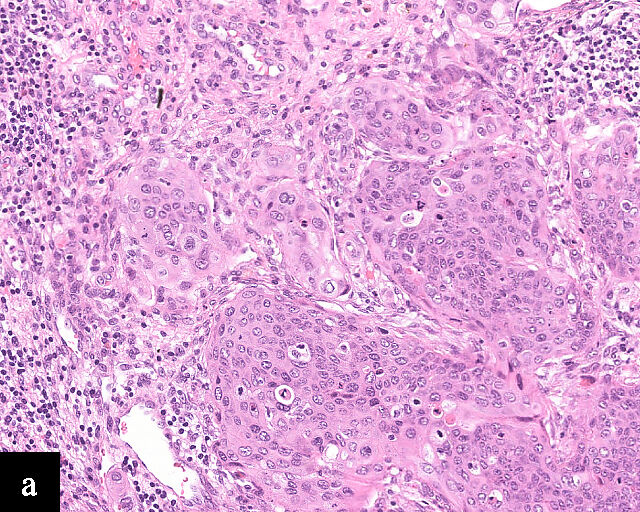

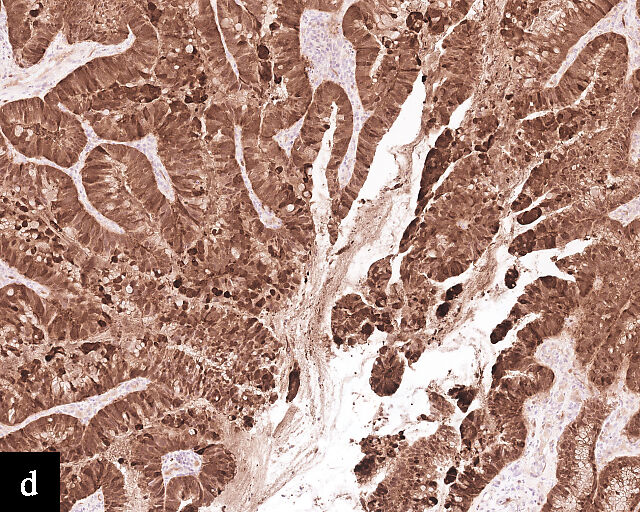

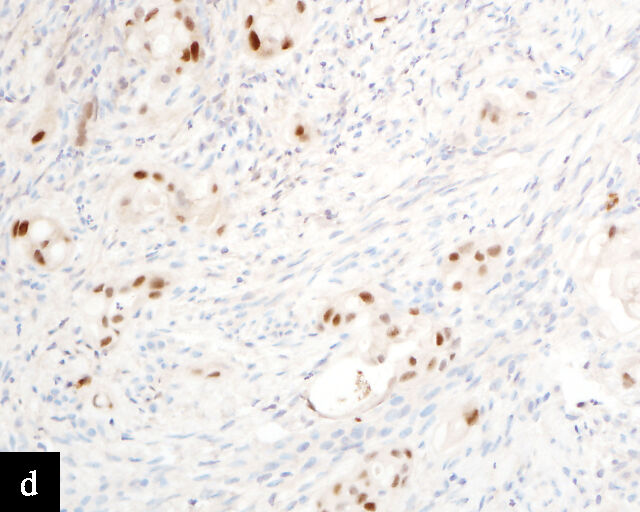

Histological sections of HPV-associated carcinoma of the cervix. Squamous cell carcinoma (magnification ×40; a,b) and adenocarcinoma (magnification ×20; c,d), shown with H&E stain (a,c) and p16 immunohistochemistry (b,d).

HPV-NEGATIVE CERVICAL CANCER

HPV-negative cervical cancers are encountered for several reasons. First, some HPV-negative cervical cancers are not primary cancers but are metastatic from other organs, such as the endometrium, ovary, gastrointestinal tract, urinary bladder or breast.

Second, cervical carcinomas may be diagnosed after a negative HPV molecular test but, in fact, still be associated with HPV, i.e. due to false-negative HPV test results.1 A study of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 2 or worse lesions that tested negative by the Cobas assay in the ATHENA study showed that a significant proportion were positive when tested with other HPV assays (Linear Array and Amplicor) indicating false-negative Cobas HPV test results.2 There are several reasons that may underlie false-negative HPV results:3 the cervical cancer may be caused by an HPV type not covered by the test; the viral copy number may be low, or inhibitors may be present in the sample; heavy blood contamination or glycerol–acetic acid treatment may affect HPV test performance; loss of the PCR-targeted region during HPV integration, improper fixation and inadequate sampling may also reduce test accuracy.

Finally, some cervical adenocarcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas, as well as their precursors, are truly HPV-independent.

The clinical, morphological, genetic and biological features of these uncommon tumors, as well as their impact on prevention, diagnosis and management, will be discussed.

TYPES OF HPV-INDEPENDENT CERVICAL CANCER

HPV-independent carcinomas comprise approximately 14% of all cervical cancers,4 and are expected to increase in proportion due to the impact of HPV vaccine.5 HPV-independent cervical carcinomas encompass HPV-independent squamous cell carcinoma, clear cell adenocarcinoma, endometrioid adenocarcinoma, gastric-type adenocarcinoma and mesonephric type adenocarcinoma. While HPV-independent cervical squamous cell carcinomas constitute a small minority of all cervical squamous cell carcinomas, cervical adenocarcinomas are more frequently HPV-independent than are squamous cell carcinomas.4

HPV-independent squamous cell carcinoma

HPV-independent squamous cell carcinomas typically occur in older women and are more commonly seen in postmenopausal age groups.6 Most studies report a rate of around 10% for HPV negativity in squamous carcinomas of the cervix.4,7,8 A link with genital prolapse has been reported and is postulated to be a result of chronic inflammation and scarring leading to cancer development.9 These squamous cell carcinomas present at a higher disease stage with a propensity for lymph-node involvement, and subsequently worse disease outcomes.10 Histologically, keratinization, hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis and an absence of adjacent HPV-associated precursor lesions favor HPV-independent squamous cell carcinoma over its HPV-dependent counterpart, but the differentiation cannot be definitively made solely based on tumor morphology.9 The lack of p16 overexpression, among other negative results in ancillary molecular testing for HPV, is necessary for the diagnosis of HPV-independent squamous cell carcinoma. The P53 mutation is enriched in these tumors and can be demonstrated by p53 immunohistochemistry or DNA sequencing.9

HPV-independent cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN)

HPV-independent CINs have recently been reported and may show verrucous, differentiated or basaloid patterns.11,12 Koilocytes are usually absent. p16 expression is absent or of non–block-type. Mutation-type aberrant p53 expression may also be present.

Clear cell adenocarcinoma

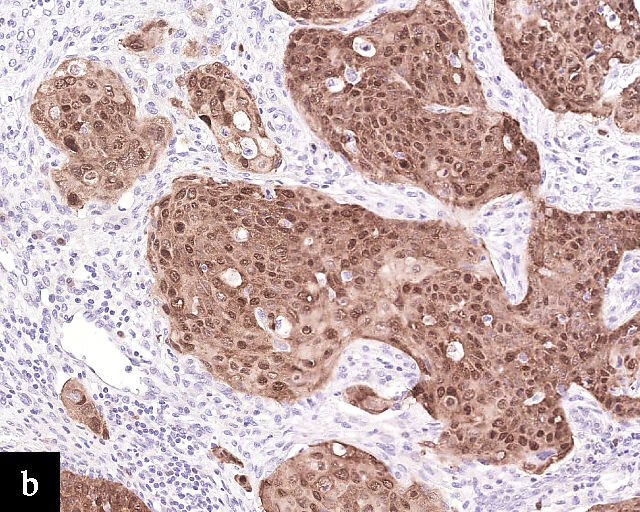

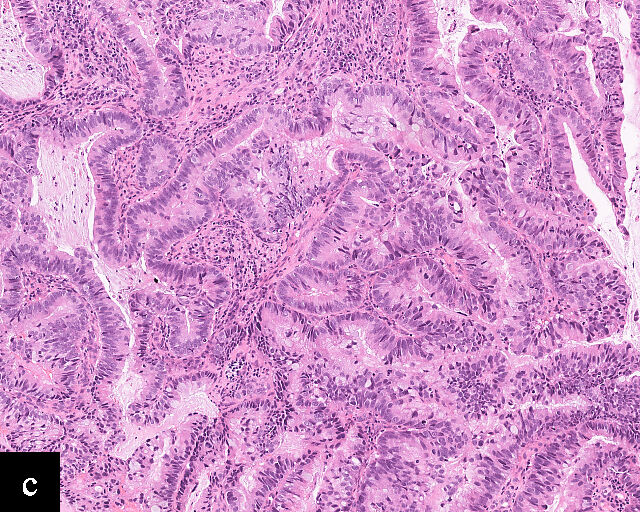

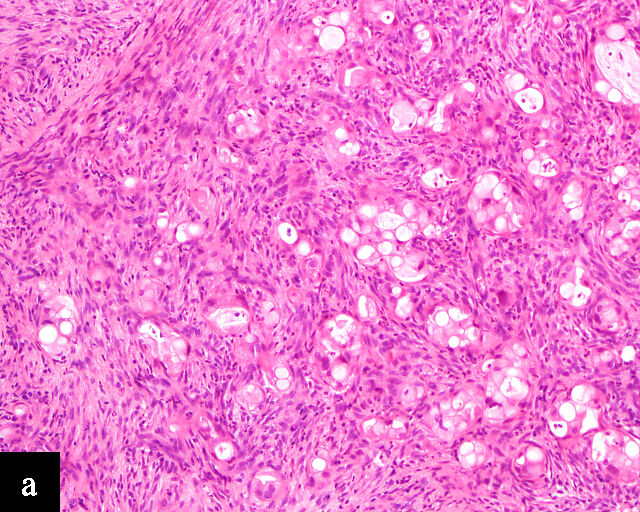

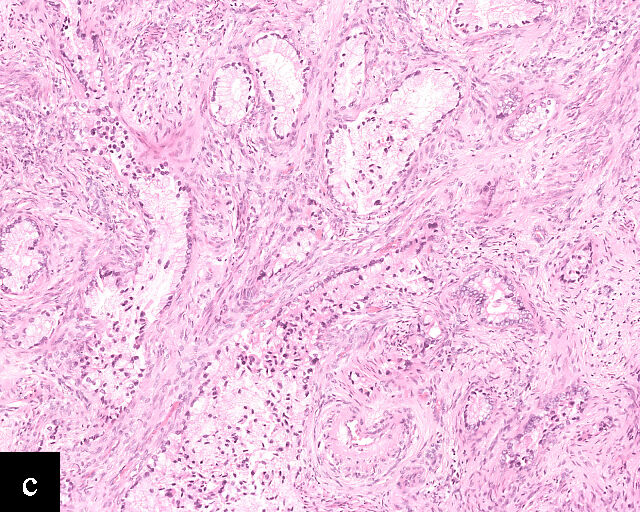

Clear cell adenocarcinomas of the cervix follow a bimodal age distribution. The first peak is observed at late adolescence/early adulthood13,14 and is associated with in-utero exposure to diethylstilbestrol (DES). The median age at presentation for clear cell adenocarcinoma not related to DES exposure is 48 years15 and constitutes the second peak. Its histological appearance resembles that of clear cell adenocarcinomas from other parts of the female genital tract (uterine corpus and ovaries), in particular tumor cells displaying overt nuclear atypia and a characteristic clear cytoplasm, arranged in variable destructive growth patterns16 (Figure 2a). Clear cell adenocarcinomas of the cervix share common immunophenotypic features with upper female genital tract carcinomas, notably PAX8 positivity and non-diffuse p16 expression17 (Figure 3a,b). Limited data from case series indicate that mutations in CMTM5 and WWTR1 are relatively frequently detected in clear cell adenocarcinomas of the cervix.18,19

2

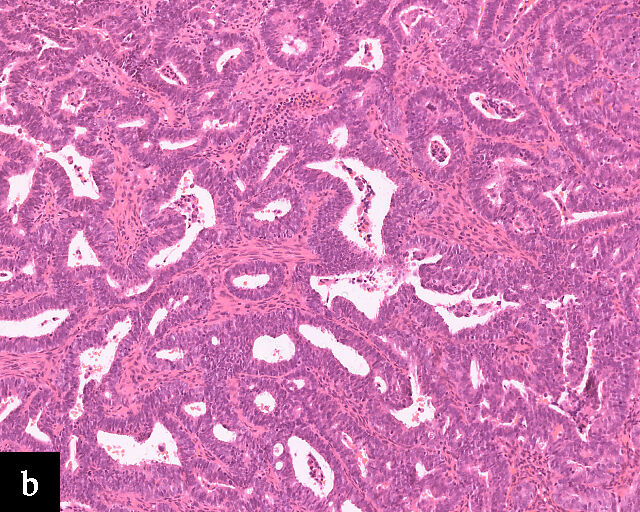

Histological sections of HPV-independent cervical carcinomas. (a) Clear cell adenocarcinoma. (b) Endometrioid adenocarcinoma. (c) Well-differentiated gastric-type adenocarcinoma. (d) Poorly differentiated gastric-type adenocarcinoma. H&E stain. Magnification ×20.

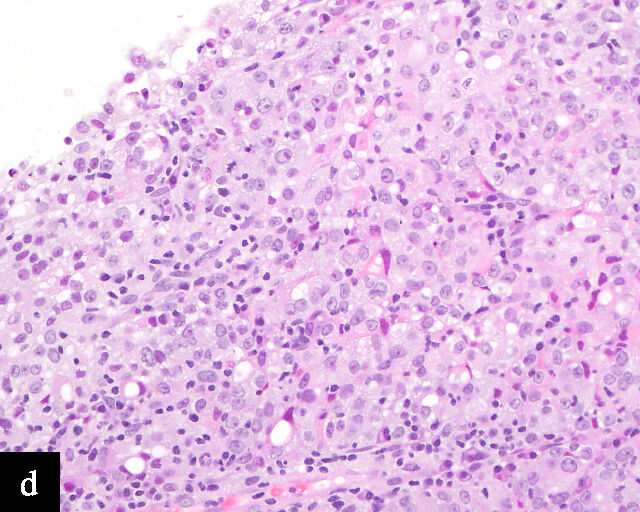

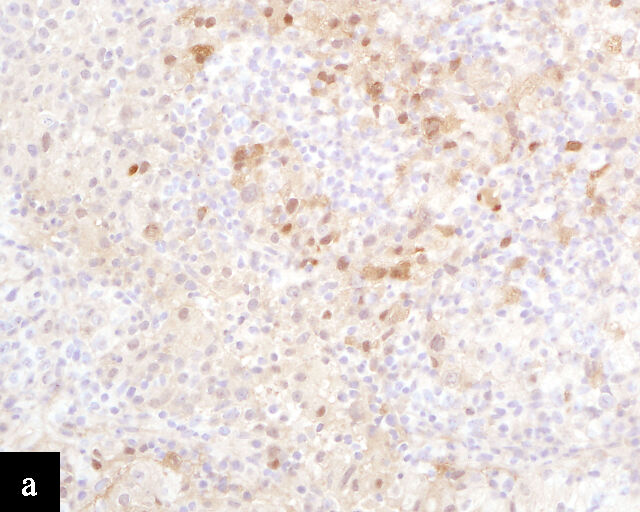

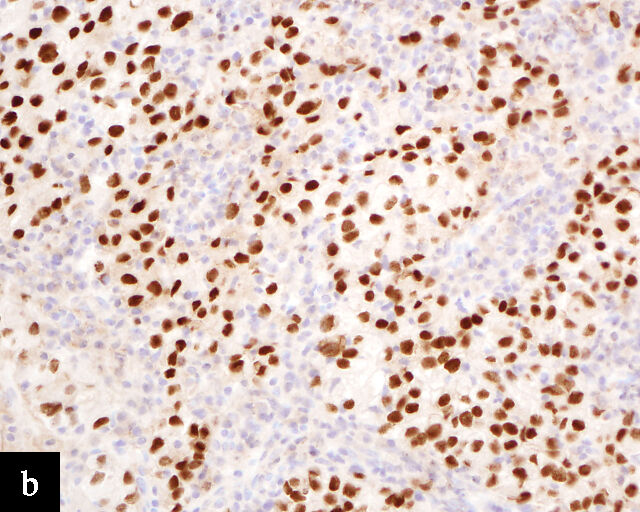

3

Immunohistochemical profile of HPV-independent cervical carcinomas. (a,b) Clear cell adenocarcinoma. (c,d) Gastric-type adenocarcinoma. HPV-independent cervical carcinomas do not show p16 diffuse expression (a,c) and are PAX8 positive (b,d). Magnification ×20.

Endometrioid adenocarcinoma

Primary cervical endometrioid adenocarcinomas are morphologically identical to endometrioid adenocarcinomas of the endometrium and ovaries17 (Figure 2b). The diagnosis can be made only when secondary involvement, particularly cervical involvement by endometrial endometrioid adenocarcinoma, is thoroughly excluded. These tumors are believed to arise from endometriosis of the cervix, which may occasionally be identified in proximity to the invasive adenocarcinoma component.17 In addition to PAX8 positivity, estrogen-receptor and progesterone-receptor immunoreactivity differentiates endometrioid adenocarcinomas from HPV-associated adenocarcinomas of the cervix. Genomic analyses have identified a subset of cervical carcinomas, mostly HPV-negative adenocarcinomas, that show enrichment for ARID1A, KRAS and PTEN mutations,20 which correlate with these tumors.

Of note, the 2020 World Health Organization Classification of Tumours considers serous carcinomas identified in the cervix to represent metastasis or secondary involvement from ovarian or endometrial primaries,21 and therefore not a histotype compatible with a cervical primary.

Gastric-type adenocarcinoma

Peutz–Jeghers syndrome (germline STK11) and somatic STK11 mutations are detected in a significant proportion of cervical gastric-type adenocarcinomas.22 Among all HPV-independent cervical adenocarcinomas, the reported incidence of gastric-type adenocarcinoma is the highest,23 thus clinicopathological and outcome data are relatively better defined for this entity.

Gastric-type adenocarcinomas frequently present at a late stage (parametrial involvement, ovarian and lymph node metastasis) with unfavorable histopathological features (lymphovascular invasion and positive peritoneal cytology) and significantly worse disease-free and overall survival compared to HPV-associated endocervical adenocarcinomas.24 Macroscopically, these tumors have been associated with a ‘barrel-shaped’ cervix, attributed to deep invasion and induction of desmoplasia, leading to diffuse enlargement and thickening of the cervix.25 The histological appearance of these tumors is diverse. Well-differentiated forms (Figure 2c) can be difficult to distinguish from non-lesional cervical glands, which is reflected in the older terminology ‘adenoma malignum’ and ‘minimal deviation adenocarcinoma’. These historically referred to gastric-type adenocarcinomas that exhibit bland morphological features.22 In contract, poorly differentiated tumors can display variable architectural patterns, ranging from irregular incomplete, glands to solid nests or single cells in which glandular differentiation is not readily evident26 (Figure 2d).

Gastric-type adenocarcinoma of the cervix produces neutral mucin and is termed ‘gastric-type’ because neutral mucin is commonly found in gastric adenocarcinomas.27 Its phenotypic resemblance to gastric adenocarcinoma can also be seen in its clear-to-pale eosinophilic, abundant cytoplasm28 and expression of HIK1083 (gastric O-glycan),29 MUC6 (gastric mucin)30 and TFF2 (gastric mucosal peptide).31 As compared to other HPV-independent adenocarcinomas, PAX8 expression is variable in gastric-type adenocarcinomas32 (Figure 3c,d). Mutations in TP53, CDKN2A, KRAS, ERBB2 and ERBB3 (≥10%)33,34 are found in gastric-type adenocarcinomas.

Mesonephric adenocarcinoma

Mesonephric adenocarcinomas are derived from mesonephric duct remnants.35 Mesonephric duct remnants are vestiges from the regressed mesonephric ducts that form the male reproductive organs during embryonic development, and are located along the female genital tract, particularly along the lateral wall of cervix.35 Although associated with embryonic remnants, mesonephric adenocarcinomas classically present in postmenopausal women.35 The outcomes of mesonephric adenocarcinomas of the cervix, endometrium and ovary are similarly poor, with an increased incidence of lung metastasis.36 These tumors are morphologically distinct, exhibiting a mixed architectural pattern with tubular structures, intraluminal eosinophilic secretions and papillary thyroid carcinoma-like nuclear features (nuclear angulation, grooves and pseudoinclusions).37 Adjacent mesonephric remnants or mesonephric hyperplasia may be present. Mesonephric adenocarcinomas display a unique immunoprofile with reciprocal expression of GATA3 and TTF1, and luminal CD10 positivity37 PAX8 is also frequently positive in mesonephric lesions.38 KRAS mutation is nearly ubiquitous in mesonephric adenocarcinomas and serves both as a diagnostic and targetable therapeutic marker39 (Table 1).

HPV-independent adenocarcinoma in situ

The relatively more commonly reported HPV-independent adenocarcinoma in situ refers to non-invasive gastric-type adenocarcinoma in situ or atypical lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia (LEGH) featuring gastrointestinal differentiation and absence or non-block p16 expression.40,41 Aberrant p53 mutant type expression and Claudin 18 immunoreactivity may help in the diagnosis.42 They are often found adjacent to invasive gastric-type adenocarcinoma and the independent clinical outcome of such lesions is still not clear. Some may be associated with synchronous mucinous metaplasia and neoplasia of the female genital tract and Peutz–Jeghers syndrome.43

Carcinoma type | Pathogenesis | Histology | Molecular features |

Squamous cell carcinoma (HPV-independent) | Postmenopausal age Association with prolapse | Keratinization Hyperkeratosis Parakeratosis | p53 overexpression P53 mutation |

Clear cell adenocarcinoma | DES-related cases present early DES-independent cases present later | Similar to clear cell adenocarcinoma of the uterine corpus and ovaries |

|

Endometrioid adenocarcinoma | Association with endometriosis | Similar to endometrioid adenocarcinomas of the uterine corpus and ovaries | ARID1A, KRAS and PTEN mutations |

Gastric-type adenocarcinoma | Peutz–Jeghers syndrome | Clear to pale eosinophilic and abundant cytoplasm | STK11 mutation |

Mesonephric type adenocarcinoma | Arise from mesonephric duct remnants | Tubular pattern Intraluminal eosinophilic secretions Papillary thyroid carcinoma-like nuclei Adjacent mesonephric components | KRAS mutation |

DES, diethylstilbestrol.

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

HPV-independent cervical carcinoma poses challenges with regards to detection, pathological diagnosis and clinical management owing to its unique repertoire of clinicopathological characteristics. For one, HPV-independent carcinomas occur mostly in postmenopausal women, with DES-associated clear cell adenocarcinomas presenting as early as in teenagers.14 These populations are socioeconomically more vulnerable than are independent adults, in which HPV-associated carcinomas most commonly present.46 There is conflicting evidence on the effect of age on the outcomes of cervical cancer depending on the cut-off adopted for analysis.47,48,49 However, results from Barben et al. defining older women as ≥ 70 years demonstrated worse short-, medium- and long-term overall survival with advanced age.47 Regardless, outcomes of HPV-independent cervical carcinomas, including recurrence-free, disease-free and overall survival, are inferior to those of HPV-associated cervical carcinoma.50

LIMITATIONS OF HPV TESTING FOR CERVICAL CANCER

In terms of epidemiology, HPV-associated precancerous lesions and HPV-associated cervical carcinomas are preventable by HPV vaccination,51 and decreases in incidence and mortality related to cervical carcinomas have been observed in regions in which effective population-level HPV vaccination has been adopted.52 As a result, the incidence of HPV-independent carcinomas is gaining increased clinical significance.53 Because these carcinomas are relatively uncommon and morphologically diverse, encompassing multiple morphologically distinct subtypes of adenocarcinomas with a wide variation in degree of differentiation,53 diagnosis by cervical cytology is challenging54 (Figure 4). Even so, cytomorphological assessment may allow the detection of HPV-independent cervical carcinomas, particularly morphologically high-grade tumors such as HPV-independent squamous cell carcinomas and clear cell adenocarcinomas.55 On the other hand, the absence of detectable precursor lesions on cytologic specimens, the subtle or non-HPV-related cytologic features of these tumors, and potential false reassurance from negative HPV testing can make HPV-independent adenocarcinomas more difficult to recognize microscopically. Consequently, the false-negative rate for cervical cytology in HPV-independent adenocarcinomas may be higher than that in HPV-associated adenocarcinomas.56

4

Gastric-type adenocarcinoma on cervical cytology.

In an HPV testing standalone approach, without cytological evaluation, HPV-independent cervical carcinomas would likely not be detected on screening. It has also been reported that a proportion of girls receiving HPV vaccination and their parents might erroneously assume that the vaccine entirely removes the risk of developing cervical cancer and that further cervical screening is not required.57 Such factors contribute to HPV-independent cervical carcinoma presenting at more advanced stages than HPV-associated cervical carcinomas.44

DIAGNOSTIC CONSIDERATIONS

The pathological diagnosis of HPV-associated cervical carcinoma is relatively uncomplicated, as its clinicopathological features are well defined.58 A previous positive cervical cytology or HPV test result is useful in supporting the diagnosis. The histological features of HPV-associated cervical carcinoma are well studied, with a much narrower spectrum consisting mostly of squamous cell carcinomas and a minority of adenocarcinomas.59 The presence of concurrent precursor lesions (squamous intraepithelial lesion and adenocarcinoma in situ) in histological sections serves as another helpful diagnostic feature. Finally, diffuse overexpression of p16 is a robust and sensitive immunohistochemical marker that identifies HPV-associated precancerous lesions and carcinomas, and often sees use in the diagnosis of these lesions in small biopsies.60

In contrast, HPV-independent cervical carcinoma, despite a trend in increasing incidence, remains uncommon and relatively unfamiliar to the general pathologist and gynecologist. The diverse morphological appearance of HPV-independent cervical carcinomas leads to a multitude of diagnostic considerations.61 Diagnosing early and well-differentiated HPV-independent cervical carcinomas requires extensive experience in gynecologic pathology, with challenging pitfalls such as differentiating mesonephric adenocarcinoma from florid mesonephric hyperplasia35 and recognizing well-differentiated gastric-type adenocarcinomas that radiologically mimic Nabothian cysts and histologically resemble normal structures.62 The absence of HPV-positive test results and identifiable precursor lesions reduces diagnostic certainty. The differential diagnosis of HPV-independent cervical carcinomas includes non-malignant cervical lesions, HPV-positive cervical carcinomas, endometrial and ovarian neoplasms and extragenital tumors.63 HPV testing, p16 and PAX8 immunohistochemistry can aid in distinguishing between HPV-associated and HPV-independent cervical carcinomas; however, they do not reliably separate HPV-independent cervical carcinomas from benign or malignant lesions of the upper female genital tract or from extragenital tumors37,38 (Table 2).

2

Clinicopathological comparison between HPV-associated and HPV-independent cervical carcinomas.1,5,12,24,35,52

| HPV-associated cervical carcinoma | HPV-independent cervical carcinoma |

Demographics | Reproductive age | More commonly postmenopausal |

Epidemiology | Preventable by HPV vaccination Decreasing incidence | Not preventable by HPV vaccination Increasing relative incidence among cervical cancers |

Screening | Higher detection rate Detectable by HPV testing | Lower detection rate Undetectable by HPV screening |

Presentation | Earlier stage, particularly with screening | More often later stage |

Diagnosis | Well understood histomorphology and clinicopathological features | Morphologically diverse and challenging to diagnose Well-differentiated carcinomas resemble normal structures |

Histology | Vast majority squamous cell carcinomas | Adenocarcinomas more common than squamous cell carcinomas Specific entities with specific histomorphology |

Outcome | Better disease-specific and overall survival | Shorter disease-specific and overall survival |

OPPORTUNITIES FOR TREATMENT

Other than surgery, traditional chemotherapy and radiotherapy, the options for targeted therapy for HPV-associated cervical carcinomas are limited. Approved agents, such as the HER2 antibody-drug conjugate trastuzumab deruxtecan64 and PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors65 are indicated for pan solid tumors, thus cannot be considered as specific treatments for HPV-associated cervical carcinomas. However, targeted therapy tailored to specific cancers often exhibits excellent efficacy, as evidenced by tyrosine kinase inhibitors acting on EGFR, ROS1 and ALK mutations in non-small cell lung carcinomas.66

Because HPV-independent cervical carcinomas encompass a broad range of subtypes, the pathogenesis and subsequent immunophenotypic and genotypic features of each entity differ and may represent potential targets for personalized treatment. KRAS mutations are defining features of mesonephric adenocarcinoma,39 and are also common in endometrioid carcinomas,67 including the targetable KRAS G12C mutation,37 which can be treated with adagrasib or sotorasib.68 Inhibitors targeting other KRAS mutations are currently under active investigation and the arsenal against KRAS mutated carcinomas may be expanded in the future.69 Another potential targeted therapy is zolbetuximab, a monoclonal antibody against claudin 18.2.70 Claudin 18.2 is aberrantly expressed primarily in pancreatic, gastric (including gastroesophageal) and biliary carcinomas,71,72 thus a specific target for drug action. With their similarity to gastric carcinomas, gastric-type adenocarcinomas of the cervix have also been reported to express claudin 18.2, providing a potential basis for targeted treatment.73

Among HPV-independent cervical carcinomas, clear cell adenocarcinomas have been reported to more frequently exhibit mismatch-repair protein deficiency and high PD-L1 expression, both of which are favorable predictors of response to immune checkpoint inhibitors.74 HER2 overexpression and amplification are also reported in gastric-type and clear cell adenocarcinomas at greater rates than in HPV-associated cervical adenocarcinomas, but supporting data are limited to a small number of cases.75

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- The clinical significance of HPV-independent cervical carcinomas is increasing with the relative decrease of HPV-associated cervical carcinomas due to HPV vaccination.

- HPV-independent cervical carcinomas encompass a wide range of subtypes, each with individual pathogenesis, clinical associations, and histological and molecular features.

- Screening, detection and histological diagnosis of HPV-independent cervical carcinomas are difficult, and patients often present at later stages with worse outcomes.

- Specific molecular aberrations and biomarker profiles of certain HPV-independent cervical carcinomas offer promising opportunities for targeted therapy.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) of this chapter declare that they have no interests that conflict with the contents of the chapter.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

REFERENCES

Blatt AJ, Kennedy R, Luff RD, Austin RM, Rabin DS. Comparison of cervical cancer screening results among 256,648 women in multiple clinical practices. Cancer Cytopathol. 2015;123(5):282–8. Epub 20150410. doi: 10.1002/cncy.21544. PubMed PMID: 25864682; PMCID: PMC4654274. | |

Petry KU, Cox JT, Johnson K, Quint W, Ridder R, Sideri M, Wright TC, Jr., Behrens CM. Evaluating HPV-negative CIN2+ in the ATHENA trial. Int J Cancer. 2016;138(12):2932–9. Epub 20160302. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30032. PubMed PMID: 26851121; PMCID: PMC5069615. | |

Prétet JL, Arroyo Mühr LS, Cuschieri K, Fellner MD, Correa RM, Picconi MA, Garland SM, Murray GL, Molano M, Peeters M, Van Gucht S, Lambrecht C, Broeck DV, Padalko E, Arbyn M, Lepiller Q, Brunier A, Silling S, Søreng K, Christiansen IK, Poljak M, Lagheden C, Yilmaz E, Eklund C, Thapa HR, Querec TD, Unger ER, Dillner J. Human papillomavirus negative high grade cervical lesions and cancers: Suggested guidance for HPV testing quality assurance. J Clin Virol. 2024;171:105657. Epub 20240220. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2024.105657. PubMed PMID: 38401369; PMCID: PMC11863830. | |

Clifford GM, Smith JS, Plummer M, Muñoz N, Franceschi S. Human papillomavirus types in invasive cervical cancer worldwide: a meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2003;88(1):63–73. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600688. PubMed PMID: 12556961; PMCID: PMC2376782. | |

Lynge E, Thamsborg L, Larsen LG, Christensen J, Johansen T, Hariri J, Christiansen S, Rygaard C, Andersen B. Prevalence of high-risk human papillomavirus after HPV-vaccination in Denmark. Int J Cancer. 2020;147(12):3446–52. Epub 20200629. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33157. PubMed PMID: 32542644; PMCID: PMC7689747. | |

Kir G, Erbagci A, Özen F, Sayit D, Karateke A. HPV-independent squamous sell carcinoma of cervix: a clinicopathological, immunohistochemical, and molecular analysis of six cases. Virchows Arch. 2025. Epub 20250510. doi: 10.1007/s00428-025-04113-6. PubMed PMID: 40347270. | |

Jiang W, Marshall Austin R, Li L, Yang K, Zhao C. Extended human papillomavirus genotype distribution and cervical cytology results in a large cohort of Chinese women with invasive cervical cancers and high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions. American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2018;150(1):43–50. | |

Kulhan M, Bilgi A, Avci F, Ucar M, Celik C, Kulhan N. Is HPV-negative cervical carcinoma a different type of cervical cancer? European Review for Medical & Pharmacological Sciences. 2023;27(19). | |

Horn LC, Brambs CE, Aktas B, Dannenmann A, Einenkel J, Höckel M, Krücken I, Taubenheim S, Teichmann G, Obeck U, Stiller M, Höhn AK. Human Papilloma Virus-Independent/p53abnormal Keratinizing Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Uterine Cervix Associated With Uterine Prolapse. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2025;44(1):2–14. Epub 20240701. doi: 10.1097/pgp.0000000000001040. PubMed PMID: 38959413. | |

Nicolás I, Marimon L, Barnadas E, Saco A, Rodríguez-Carunchio L, Fusté P, Martí C, Rodriguez-Trujillo A, Torne A, Del Pino M, Ordi J. HPV-negative tumors of the uterine cervix. Mod Pathol. 2019;32(8):1189–96. Epub 20190325. doi: 10.1038/s41379-019-0249-1. PubMed PMID: 30911077. | |

Regauer S, Reich O, Kashofer K. HPV-negative Squamous Cell Carcinomas of the Cervix With Special Focus on Intraepithelial Precursor Lesions. Am J Surg Pathol. 2022;46(2):147–58. doi: 10.1097/pas.0000000000001778. PubMed PMID: 34387215. | |

Regauer S, Reich O. The Histologic and Molecular Spectrum of Highly Differentiated HPV-independent Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia. Am J Surg Pathol. 2023;47(8):942–9. Epub 20230607. doi: 10.1097/pas.0000000000002067. PubMed PMID: 37283469. | |

Huo D, Anderson D, Palmer JR, Herbst AL. Incidence rates and risks of diethylstilbestrol-related clear-cell adenocarcinoma of the vagina and cervix: Update after 40-year follow-up. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;146(3):566–71. Epub 20170706. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.06.028. PubMed PMID: 28689666. | |

Herbst AL, Anderson D. Clear cell adenocarcinoma of the vagina and cervix secondary to intrauterine exposure to diethylstilbestrol. Semin Surg Oncol. 1990;6(6):343–6. doi: 10.1002/ssu.2980060609. PubMed PMID: 2263810. | |

Zeng J, Jiang W, Li K, Zhang M, Chen J, Duan Y, Li Q, Yin R. Clinical and pathological characteristics of cervical clear cell carcinoma in patients not exposed to diethylstilbestrol: a comprehensive analysis of 49 cases. Front Oncol. 2024;14:1430742. Epub 20240711. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2024.1430742. PubMed PMID: 39055567; PMCID: PMC11269214. | |

Matias-Guiu X, Lerma E, Prat J. Clear cell tumors of the female genital tract. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1997;14(4):233–9. PubMed PMID: 9383823. | |

Stolnicu S, Barsan I, Hoang L, Patel P, Terinte C, Pesci A, Aviel-Ronen S, Kiyokawa T, Alvarado-Cabrero I, Pike MC, Oliva E, Park KJ, Soslow RA. International Endocervical Adenocarcinoma Criteria and Classification (IECC): A New Pathogenetic Classification for Invasive Adenocarcinomas of the Endocervix. The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 2018;42(2). | |

Su Y, Zhang Y, Zhou M, Zhang R, Chen S, Zhang L, Wang H, Zhang D, Zhang T, Li X, Zhang C, Wang B, Yuan S, Zhang M, Zhou Y, Cao L, Zhang M, Luo J. Genetic alterations in juvenile cervical clear cell adenocarcinoma unrelated to human papillomavirus. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1211888. Epub 20230816. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1211888. PubMed PMID: 37654657; PMCID: PMC10466801. | |

Kim SH, Basili T, Dopeso H, Da Cruz Paula A, Bi R, Issa Bhaloo S, Pareja F, Li Q, da Silva EM, Zhu Y, Hoang T, Selenica P, Murali R, Chan E, Wu M, Derakhshan F, Maroldi A, Hanlon E, Ferreira CG, Lapa ESJR, Abu-Rustum NR, Zamarin D, Chandarlapaty S, Matrai C, Yoon JY, Reis-Filho JS, Park KJ, Weigelt B. Recurrent WWTR1 S89W mutations and Hippo pathway deregulation in clear cell carcinomas of the cervix. J Pathol. 2022;257(5):635–49. Epub 20220520. doi: 10.1002/path.5910. PubMed PMID: 35411948; PMCID: PMC9881397. | |

Burk RD, Chen Z, Saller C, Tarvin K, Carvalho AL, Scapulatempo-Neto C, Silveira HC, Fregnani JH, Creighton CJ, Anderson ML, Castro P, Wang SS, et al. Integrated genomic and molecular characterization of cervical cancer. Nature. 2017;543(7645):378–84. doi: 10.1038/nature21386. | |

Female Genital Tumours. WHO Classification of Tumours 5th Edition, Volume 4: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2020. | |

Kuragaki C, Enomoto T, Ueno Y, Sun H, Fujita M, Nakashima R, Ueda Y, Wada H, Murata Y, Toki T, Konishi I, Fujii S. Mutations in the STK11 Gene Characterize Minimal Deviation Adenocarcinoma of the Uterine Cervix. Laboratory Investigation. 2003;83(1):35–45. doi: 10.1097/01.LAB.0000049821.16698.D0. | |

Nishio H, Matsuda R, Iwata T, Yamagami W. Gastric-type adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix: clinical features and future directions. Japanese Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2024;54(5):516–20. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyae019. | |

Nishio S, Mikami Y, Tokunaga H, Yaegashi N, Satoh T, Saito M, Okamoto A, Kasamatsu T, Miyamoto T, Shiozawa T, Yoshioka Y, Mandai M, Kojima A, Takehara K, Kaneki E, Kobayashi H, Kaku T, Ushijima K, Kamura T. Analysis of gastric-type mucinous carcinoma of the uterine cervix – An aggressive tumor with a poor prognosis: A multi-institutional study. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;153(1):13–9. Epub 20190129. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2019.01.022. PubMed PMID: 30709650. | |

Yang Y, Zhu X, Zhou Y, Li Z, Liu J, Fang M. Endocervical adenocarcinoma of the gastric type: a case report and literature review. Front Oncol. 2025;15:1457253. Epub 20250513. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2025.1457253. PubMed PMID: 40432921; PMCID: PMC12106436. | |

Nishio S. Current status and molecular biology of human papillomavirus-independent gastric-type adenocarcinoma of the cervix. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2023;49(4):1106–13. Epub 20230209. doi: 10.1111/jog.15578. PubMed PMID: 36759334. | |

Cook HC. Neutral mucin content of gastric carcinomas as a diagnostic aid in the identification of secondary deposits. Histopathology. 1982;6(5):591–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1982.tb02753.x. PubMed PMID: 6183187. | |

Kojima A, Mikami Y, Sudo T, Yamaguchi S, Kusanagi Y, Ito M, Nishimura R. Gastric morphology and immunophenotype predict poor outcome in mucinous adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31(5):664–72. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213434.91868.b0. PubMed PMID: 17460448. | |

Iijima M, Nakayama J, Nishizawa T, Ishida A, Ishii K, Ota H, Katsuyama T, Saida T. Usefulness of monoclonal antibody HIK1083 specific for gastric O-glycan in differentiating cutaneous metastasis of gastric cancer from primary sweat gland carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29(5):452–6. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e31814691e7. PubMed PMID: 17890913. | |

De Bolós C, Garrido M, Real FX. MUC6 apomucin shows a distinct normal tissue distribution that correlates with Lewis antigen expression in the human stomach. Gastroenterology. 1995;109(3):723–34. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90379-8. PubMed PMID: 7657100. | |

Takako K, Hoang L, Terinte C, Pesci A, Aviel-Ronen S, Alvarado-Cabrero I, Oliva E, Park KJ, Soslow RA, Stolnicu S. Trefoil Factor 2 (TFF2) as a Surrogate Marker for Endocervical Gastric-type Carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2021;40(1):65–72. doi: 10.1097/pgp.0000000000000680. PubMed PMID: 32897966; PMCID: PMC7725933. | |

Zhou J, Zhang X, Mao W, Zhu Y, Yan L, Jiang J, Zhang M. Pathological features of gastric-type endocervical adenocarcinoma: A report of two cases. Oncol Lett. 2024;27(4):149. Epub 20240209. doi: 10.3892/ol.2024.14282. PubMed PMID: 38406594; PMCID: PMC10884787. | |

Ehmann S, Sassine D, Straubhar AM, Praiss AM, Aghajanian C, Alektiar KM, Broach V, Cadoo KA, Jewell EL, Boroujeni AM, Kyi C, Leitao MM, Mueller JJ, Murali R, Bhaloo SI, O'Cearbhaill RE, Park KJ, Sonoda Y, Weigelt B, Zamarin D, Abu-Rustum N, Friedman CF. Gastric-type adenocarcinoma of the cervix: Clinical outcomes and genomic drivers. Gynecol Oncol. 2022;167(3):458–66. Epub 20221015. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2022.10.003. PubMed PMID: 36253302; PMCID: PMC10155605. | |

Selenica P, Alemar B, Matrai C, Talia KL, Veras E, Hussein Y, Oliva E, Beets-Tan RGH, Mikami Y, McCluggage WG, Kiyokawa T, Weigelt B, Park KJ, Murali R. Massively parallel sequencing analysis of 68 gastric-type cervical adenocarcinomas reveals mutations in cell cycle-related genes and potentially targetable mutations. Mod Pathol. 2021;34(6):1213–25. Epub 20201214. doi: 10.1038/s41379-020-00726-1. PubMed PMID: 33318584; PMCID: PMC8154628. | |

Dierickx A, Göker M, Braems G, Tummers P, Van den Broecke R. Mesonephric adenocarcinoma of the cervix: Case report and literature review. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2016;17:7–11. Epub 20160507. doi: 10.1016/j.gore.2016.05.002. PubMed PMID: 27354991; PMCID: PMC4898911. | |

Pors J, Segura S, Chiu DS, Almadani N, Ren H, Fix DJ, Howitt BE, Kolin D, McCluggage WG, Mirkovic J, Gilks B, Park KJ, Hoang L. Clinicopathologic Characteristics of Mesonephric Adenocarcinomas and Mesonephric-like Adenocarcinomas in the Gynecologic Tract: A Multi-institutional Study. Am J Surg Pathol. 2021;45(4):498–506. doi: 10.1097/pas.0000000000001612. PubMed PMID: 33165093; PMCID: PMC7954854. | |

Xing D, Liang SX, Gao FF, Epstein JI. Mesonephric Adenocarcinoma and Mesonephric-like Adenocarcinoma of the Urinary Tract. Modern Pathology. 2023;36(1):100031. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.modpat.2022.100031. | |

Goyal A, Yang B. Differential patterns of PAX8, p16, and ER immunostains in mesonephric lesions and adenocarcinomas of the cervix. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2014;33(6):613–9. doi: 10.1097/pgp.0000000000000102. PubMed PMID: 25272301. | |

Brambs CE, Horn LC, Hiller R, Krücken I, Braun C, Christmann C, Monecke A, Höhn AK. Mesonephric-like adenocarcinoma of the female genital tract: possible role of KRAS-targeted treatment-detailed molecular analysis of a case series and review of the literature for targetable somatic KRAS-mutations. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023;149(17):15727–36. Epub 20230905. doi: 10.1007/s00432-023-05306-9. PubMed PMID: 37668797; PMCID: PMC10620254. | |

Mikami Y, McCluggage WG. Endocervical glandular lesions exhibiting gastric differentiation: an emerging spectrum of benign, premalignant, and malignant lesions. Adv Anat Pathol. 2013;20(4):227–37. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e31829c2d66. PubMed PMID: 23752085. | |

Talia KL, Stewart CJR, Howitt BE, Nucci MR, McCluggage WG. HPV-negative Gastric Type Adenocarcinoma In Situ of the Cervix: A Spectrum of Rare Lesions Exhibiting Gastric and Intestinal Differentiation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41(8):1023–33. doi: 10.1097/pas.0000000000000855. PubMed PMID: 28394803. | |

Lin LH, Kaur H, Kolin DL, Nucci MR, Parra-Herran C. Claudin-18 and Mutation Surrogate Immunohistochemistry in Gastric-type Endocervical Lesions and their Differential Diagnoses. Am J Surg Pathol. 2025;49(3):206–16. Epub 20241206. doi: 10.1097/pas.0000000000002342. PubMed PMID: 39652450. | |

Mikami Y, Kiyokawa T, Sasajima Y, Teramoto N, Wakasa T, Wakasa K, Hata S. Reappraisal of synchronous and multifocal mucinous lesions of the female genital tract: a close association with gastric metaplasia. Histopathology. 2009;54(2):184–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2008.03202.x. PubMed PMID: 19207943. | |

He J, Tu Lu Weng Jiang G, Zeng L. Analysis of the differences between HPV-independent and HPV-related cervical adenocarcinoma. Front Oncol. 2025;15:1544207. Epub 20250417. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2025.1544207. PubMed PMID: 40313251; PMCID: PMC12043462. | |

Park HM, Lee SS, Eom DW, Kang GH, Yi SW, Sohn WS. Endometrioid adenocarcinoma arising from endometriosis of the uterine cervix: a case report. J Korean Med Sci. 2009;24(4):767–71. Epub 20090730. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2009.24.4.767. PubMed PMID: 19654969; PMCID: PMC2719211. | |

Choi S, Ismail A, Pappas-Gogos G, Boussios S. HPV and Cervical Cancer: A Review of Epidemiology and Screening Uptake in the UK. Pathogens. 2023;12(2). Epub 20230211. doi: 10.3390/pathogens12020298. PubMed PMID: 36839570; PMCID: PMC9960303. | |

Barben J, Kamga AM, Dabakuyo-Yonli TS, Hacquin A, Putot A, Manckoundia P, Bengrine-Lefevre L, Quipourt V. Cervical cancer in older women: Does age matter? Maturitas. 2022;158:40–6. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2021.11.011. | |

Rivard C, Stockwell E, Yuan J, Isaksson Vogel R, Geller MA. Age as a prognostic factor in cervical cancer: A 10-year review of patients treated at a single institution. Gynecologic Oncology. 2016;141:102. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.04.278. | |

Accorsi GS, Zanon JR, Santos MHd, Ubinha ACF, Schmidt R, Moretti-Marques R, Baiocchi G, de Pádua Souza C, Andrade CEMdC, Reis Rd. Cervical cancer in young women: Does age impact survival in cervical cancer? European Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 2025;305:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2024.12.003. | |

Wenli D, Xianxu Z, Liron P, Chengquan Z. Human papillomavirus negative cervical cancers and precancerous lesions: prevalence, pathological and molecular features, and clinical implications. Gynecology and Obstetrics Clinical Medicine. 2025;5(1):e000160. doi: 10.1136/gocm-2024-000160. | |

Falcaro M, Soldan K, Ndlela B, Sasieni P. Effect of the HPV vaccination programme on incidence of cervical cancer and grade 3 cervical intraepithelial neoplasia by socioeconomic deprivation in England: population based observational study. BMJ. 2024;385:e077341. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2023-077341. | |

Patel C, Brotherton JM, Pillsbury A, Jayasinghe S, Donovan B, Macartney K, Marshall H. The impact of 10 years of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination in Australia: what additional disease burden will a nonavalent vaccine prevent? Euro Surveill. 2018;23(41). doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.Es.2018.23.41.1700737. PubMed PMID: 30326995; PMCID: PMC6194907. | |

Aggarwal IM, Yeo YC, Ng ZY. Human papillomavirus-independent cervical cancer and its precursor lesions. The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist. 2023;25(1):47–58. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/tog.12855. | |

Liu A, Yang M, Zou H, Gong X, Zeng C. Cytologic features of gastric-type endocervical adenocarcinoma: Three cases report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2024;103(43):e40149. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000040149. PubMed PMID: 39470523; PMCID: PMC11520992. | |

Wang R, Du Y. Cytologic features of cervical clear cell carcinoma of the cervix: Report of a case with immunocytochemical findings. Diagnostic Cytopathology. 2020;48(8):804–6. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/dc.24482. | |

Chang C-S, Na J, Lee YY, Kim T-J, Lee J-W, Kim BG, Choi CH. EP370/#835 Diagnostic accuracy of cytology test in HPV-independent cervical adenocarcinoma. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer. 2023;33:A227. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/ijgc-2023-IGCS.421. | |

Henderson L, Clements A, Damery S, Wilkinson C, Austoker J, Wilson S. 'A false sense of security'? Understanding the role of the HPV vaccine on future cervical screening behaviour: a qualitative study of UK parents and girls of vaccination age. J Med Screen. 2011;18(1):41–5. doi: 10.1258/jms.2011.010148. PubMed PMID: 21536816; PMCID: PMC3104818. | |

Wilczynski SP, Bergen S, Walker J, Liao S-Y, Pearlman LF. Human papillomaviruses and cervical cancer: Analysis of histopathologic features associated with different viral types. Human Pathology. 1988;19(6):697–704. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0046-8177(88)80176-X. | |

Adegoke O, Kulasingam S, Virnig B. Cervical cancer trends in the United States: a 35-year population-based analysis. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2012;21(10):1031–7. Epub 20120720. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2011.3385. PubMed PMID: 22816437; PMCID: PMC3521146. | |

Shain AF, Kwok S, Folkins AK, Kong CS. Utility of p16 Immunohistochemistry in Evaluating Negative Cervical Biopsies Following High-risk Pap Test Results. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42(1):69–75. doi: 10.1097/pas.0000000000000960. PubMed PMID: 29112019. | |

Yasuda M, Katoh T, Miyama Y, Honma T, Yano M, Yabuno A. Histological classification of uterine cervical adenocarcinomas: Its alteration and current status. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research. 2025;51(4):e16287. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/jog.16287. | |

Ki EY, Byun SW, Park JS, Lee SJ, Hur SY. Adenoma malignum of the uterine cervix: report of four cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:168. Epub 20130726. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-11-168. PubMed PMID: 23885647; PMCID: PMC3733704. | |

Stewart CJR, Crum CP, McCluggage WG, Park KJ, Rutgers JK, Oliva E, Malpica A, Parkash V, Matias-Guiu X, Ronnett BM. Guidelines to Aid in the Distinction of Endometrial and Endocervical Carcinomas, and the Distinction of Independent Primary Carcinomas of the Endometrium and Adnexa From Metastatic Spread Between These and Other Sites. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2019;38 Suppl 1(Iss 1 Suppl 1):S75-s92. doi: 10.1097/pgp.0000000000000553. PubMed PMID: 30550485; PMCID: PMC6296834. | |

Meric-Bernstam F, Makker V, Oaknin A, Oh D-Y, Banerjee S, González-Martín A, Jung KH, Lugowska I, Manso L, Manzano A, Melichar B, Siena S, Stroyakovskiy D, Fielding A, Ma Y, Puvvada S, Shire N, Lee J-Y. Efficacy and Safety of Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in Patients With HER2-Expressing Solid Tumors: Primary Results From the DESTINY-PanTumor02 Phase II Trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2024;42(1):47–58. doi: 10.1200/jco.23.02005. PubMed PMID: 37870536. | |

Huang W, Liu J, Xu K, Chen H, Bian C. PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors for advanced or metastatic cervical cancer: From bench to bed. Front Oncol. 2022;12:849352. Epub 20221014. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.849352. PubMed PMID: 36313730; PMCID: PMC9614140. | |

Chirieac LR, Dacic S. Targeted Therapies in Lung Cancer. Surg Pathol Clin. 2010;3(1):71–82. doi: 10.1016/j.path.2010.04.001. PubMed PMID: 20680095; PMCID: PMC2912609. | |

Sideris M, Emin EI, Abdullah Z, Hanrahan J, Stefatou KM, Sevas V, Emin E, Hollingworth T, Odejinmi F, Papagrigoriadis S, Vimplis S, Willmott F. The Role of KRAS in Endometrial Cancer: A Mini-Review. Anticancer Res. 2019;39(2):533–9. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.13145. PubMed PMID: 30711927. | |

Singhal S, Schokrpur S, Gandara D, Riess JW. KRAS G12C Inhibitors: New Drugs, A New Hope. Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 2024;19(12):1594–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2024.09.1383. | |

Tang D, Kang R. Glimmers of hope for targeting oncogenic KRAS-G12D. Cancer Gene Therapy. 2023;30(3):391–3. doi: 10.1038/s41417-022-00561-3. | |

Shah MA, Shitara K, Ajani JA, Bang Y-J, Enzinger P, Ilson D, Lordick F, Van Cutsem E, Gallego Plazas J, Huang J, Shen L, Oh SC, Sunpaweravong P, Soo Hoo HF, Turk HM, Oh M, Park JW, Moran D, Bhattacharya P, Arozullah A, Xu R-H. Zolbetuximab plus CAPOX in CLDN18.2-positive gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma: the randomized, phase 3 GLOW trial. Nature Medicine. 2023;29(8):2133–41. doi: 10.1038/s41591-023-02465-7. | |

Hong JY, An JY, Lee J, Park SH, Park JO, Park YS, Lim HY, Kim KM, Kang WK, Kim ST. Claudin 18.2 expression in various tumor types and its role as a potential target in advanced gastric cancer. Transl Cancer Res. 2020;9(5):3367–74. doi: 10.21037/tcr-19-1876. PubMed PMID: 35117702; PMCID: PMC8797704. | |

Fassan M, Kuwata T, Matkowskyj KA, Röcken C, Rüschoff J. Claudin-18.2 Immunohistochemical Evaluation in Gastric and Gastroesophageal Junction Adenocarcinomas to Direct Targeted Therapy: A Practical Approach. Mod Pathol. 2024;37(11):100589. Epub 20240802. doi: 10.1016/j.modpat.2024.100589. PubMed PMID: 39098518. | |

Yan P, Dong Y, Zhang F, Zhen T, Liang J, Shi H, Han A. Claudin18.2 expression and its clinicopathological feature in adenocarcinoma from various parts. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2024:jcp-2023–209268. doi: 10.1136/jcp-2023-209268. | |

Bulutay P, Eren Ö C, Özen Ö, Haberal AN, Kapucuoglu N. Clear cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix; an unusual HPV-independent tumor: Clinicopathological features, PD-L1 expression, and mismatch repair protein deficiency status of 16 cases. Turk J Obstet Gynecol. 2023;20(3):164–73. doi: 10.4274/tjod.galenos.2023.62819. PubMed PMID: 37667475; PMCID: PMC10478723. | |

Shi H, Shao Y, Lu W, Lu B. An analysis of HER2 amplification in cervical adenocarcinoma: correlation with clinical outcomes and the International Endocervical Adenocarcinoma Criteria and Classification. J Pathol Clin Res. 2021;7(1):86–95. Epub 20201022. doi: 10.1002/cjp2.184. PubMed PMID: 33089969; PMCID: PMC7737776. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards program CLICK HERE)