This chapter should be cited as follows:

Hall M, Shennan A, Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.416513

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Obstetrics Module

Volume 19

Pregnancy shortening: etiology, prediction and prevention

Volume Editors:

Professor Arri Coomarasamy, University of Birmingham, UK

Professor Gian Carlo Di Renzo, University of Perugia, Perugia, Italy

Professor Eduardo Fonseca, Federal University of Paraiba, Brazil

Chapter

Cervical Cerclage Revisited

First published: October 2022

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

First performed in 1902, the cervical cerclage is the mainstay surgical intervention for the prevention of spontaneous preterm birth secondary to cervical insufficiency. Currently, it is performed during an estimated 1–2% of pregnancies, although evidence for the efficacy of the procedure is often lacking. The 1950s saw publications regarding surgical technique, while controlled trials were not performed until the 1980s looking at cervical cerclage effectiveness. These trials are limited by their populations, i.e., have often been carried out in women with previous preterm birth and so are difficult to generalize to women with specific risk factors.

There are still many questions to be answered regarding cervical cerclage, including its value for certain indications and optimal surgical techniques.

THE PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF CERVICAL CHANGE

Cervical insufficiency, an alternative name for cervical incompetence, is difficult to define, diagnose, or predict as the mechanism of premature cervical change is not understood. Diagnosis is usually only made after women present with symptoms that lead to premature delivery or second-trimester pregnancy loss, i.e., for many women there are no pre-pregnancy risk factors. The integrity of the cervix is necessary to prevent ascending infection. Aetiological mechanisms of “insufficiency” include congenital or acquired weakness in the cervix itself, which predisposes to ascending infection (of the normal vaginal microbiome) leading to intra-amniotic infection and inflammation that precipitates labor. Sterile intra-uterine activity can also lead to cervical shortening, such as contractions due to bleeding secondary to placental causes. The role of cerclage in preventing delivery is not clear, but it may act as either a prophylactic or therapeutic intervention in preventing ascending infection. For this reason, history indicated and ultrasound indicated cerclages may act in different ways.

There are several factors that are known to predispose to spontaneous preterm birth (Table 1). Management should be individualized to the risk factors present as far as is possible, with modifiable risk factors managed preconceptionally or as early as possible during the pregnancy (for example, smoking cessation, dietary advice, identification, and treatment of urine infection). Cerclage can influence cervical change, but this is likely to be dependant on etiology. There is little evidence supporting cerclage use in specific pathological conditions, so whether cerclage improves outcome is unknown in many conditions. Some trials that have evaluated cerclage have included all high-risk women, with numbers not big enough to perform meaningful subgroup analysis.

1

Factors associated with spontaneous preterm birth.

High risk | Medium risk | Other factors to consider |

Previous second trimester loss (16–23 weeks) | Large loop excision of the transformation zone (≥1 cm removed) | Cervical dilatation procedure especially second trimester surgical management |

Previous spontaneous preterm birth (24–34 weeks) | Cone biopsy | Collagen abnormalities |

Previous PPROM (<34 weeks) | Previous cesarean section in labor | Multiple pregnancy |

Mullerian anomalies | Smoking | |

Ashermann’s syndrome | Low BMI | |

Previous trachelectomy | Domestic violence | |

Urine infection | ||

Bacterial vaginosis | ||

Sexually transmitted infections | ||

Short interpregnancy interval | ||

IVF | ||

High-risk HPV infection | ||

Social deprivation | ||

Maternal age >40yrs | ||

Periodontitis | ||

Teenage pregnancy | ||

Primiparity |

PPROM, prelabor preterm rupture of the membranes.

CLASSIFICATION OF CERVICAL CERCLAGE

Cervical cerclage can be classified by indication or by level of placement. Indication can be history (based on a woman having high risk of preterm birth because of a factor, or combination of factors, identified); ultrasound indicated (usually a cervix of less than 25 mm length identified between 16 and 24 weeks); or emergency cerclage with exposed membranes, also known as rescue, and hereafter referred to as an emergency cerclage.

Cerclage can be placed in one of three ways: a low cerclage (e.g., McDonald’s) is where the cerclage is inserted transvaginally without bladder mobilization; a high cerclage (e.g., Shirodkar) takes a transvaginal approach and involves bladder mobilization and cerclage placement; a transabdominal cerclage is placed higher from an abdominal approach, usually above the level of the uterosacral and cardinal ligaments.

INDICATIONS FOR CERVICAL CERCLAGE

Cervical cerclage is the operation of choice by most obstetricians for the prevention of preterm birth or second-trimester pregnancy loss in women at high risk of these outcomes owing to cervical insufficiency. In spite of the procedure being performed since the early 1900s, there is still considerable uncertainty in determining which women would most benefit from the procedure. Equally, details of technique and management are largely discretionary with little evidence base, but there is increasing focus on research to obtain more evidence.

Indications for cervical cerclage without cervical screening

Transvaginal cervical cerclage should be offered to all women with a singleton pregnancy who have had three or more spontaneous preterm births or second-trimester losses prior to 37 weeks' gestation. This is only based on a subgroup analysis suggesting that preterm birth rates before 33 weeks are halved in this group from 32 to 15%. No effect is seen in women with one or two previous preterm births or second-trimester losses.1,2 For these women, ultrasound scanning can be offered (see below).

Women who have undergone trachelectomy often have a cervical cerclage sited at the same time, as these women have a high incidence of preterm delivery. However, this should be confirmed prior to attempting to conceive, as a significant minority (33%) have not had a prophylactic suture inserted at the time of surgery.3 Women who have had a failed vaginal cerclage should also be considered for transabdominal cerclage pre-conceptually or in the first trimester if necessary (see below).4

Indications for ultrasound indicated cerclage

Women considered high risk for spontaneous preterm birth can be offered cervical screening by ultrasound, when available, every 2–4 weeks from 16 to until 24 weeks' gestation. It would be reasonable for women at intermediate risk (e.g., previous loop excision) to have a single measurement between 18 and 22 weeks. Cervical cerclage should be discussed with women in this group if their cervix measures under 25 mm.5

In women with a prior history of preterm birth who have received an ultrasound indicated cerclage, the risk of delivery at <35 weeks was roughly halved, with the benefit being greatest <15 mm.6 In women with other risk factors, including cervical surgery, the benefit is uncertain but can be considered on an individual patient basis.

Trials have not been large enough to demonstrate meaningful benefit on perinatal mortality.

Ultrasound indicated cerclage can be safely offered as an alternative to history indicated cerclage in cases where previous ultrasound indicates cerclage has been sited.7,8,9

Women being discharged at 24 weeks should be reassured that a normal cervical length at this stage confers a 90% chance of delivery after 34 weeks.

Owing to the emotional burden of previous second-trimester losses and extreme preterm birth, there is likely to be a cohort of women suitable for cervical screening who request intervention as their primary course of treatment. These women should be counseled on the risks of cervical cerclage (see below) as well as any potential benefits, with their mental well-being considered. They should be offered an individualized screening strategy that aims to meet their specific concerns as an alternative to cerclage in order to avoid unnecessary surgery. If a woman chooses to have a cerclage with such a history, it is important they are counseled that there is no evidence of benefit. Cerclage use is relatively safe, but if cerclage fails it can increase the risk of complications including serious infection.

Multiple pregnancy

The benefit of cerclage in women who are pregnant with twins or a higher-order multiple pregnancy is poorly researched, and often does not include high-risk twins.10,11 There is some evidence suggesting there is increasing benefit of cerclage in the shorter cervix (<15 mm).12 In practice the threshold for using cerclage in twins is lower when there are additional risk factors, such as cervical surgery or a history of prior preterm birth, when this becomes the indication for the cerclage.

Contraindications to cervical cerclage

Contraindications to cervical cerclage are listed in Table 2. Relative contraindications, such as lack of screening test results, should be discussed with patients and care individualized. Where there is an absolute contraindication, care should be given to ensure postnatal follow up for debriefing and planning of future pregnancies.

2

Absolute contraindications to cervical cerclage.

Absolute contraindications to cerclage |

Active preterm labor |

Clinical evidence of chorioamnionitis |

PPROM |

Active vaginal bleeding |

Lethal fetal defect |

Intrauterine death |

Follow-up care not guaranteed |

Patient does not consent |

Cerclage compared to other prophylactic therapies for the prevention of preterm birth

Both progesterone (either daily vaginal progesterone or weekly intramuscular 17-hydroxyprogesterone caproate) and the Arabin pessary have been investigated as possible preventative treatments in the management of women at high risk of spontaneous preterm birth. Progesterone is currently recommended but more evidence is needed for the Arabin pessary.13,14 A trial comparing the three (SuPPoRT) is due to report.15 Pending the results of this, it would be reasonable to discuss all three options with patients and recognize the potential benefits of one or the other of progesterone and a pessary especially among women keen to avoid surgery, or for whom surgery would be particularly high risk.

CONSIDERATIONS WHERE SCREENING IS NOT AVAILABLE

In units where cervical screening is not available due to lack of access to a suitable scanner, an experienced sonologist, or a specialist obstetrician, then transfers to a nearby unit with sufficient expertise should be offered.

When caring for a patient who is at high risk of preterm birth but for whom there is no access to screening, for example, residence in a low-income country, then the benefit of cervical cerclage needs to be weighed against a wider range of risks, such as practicalities of returning for suture removal, especially if this is an emergency. In this case, progesterone may be preferable if available.

PRE-OPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

Timing of history indicated cerclage

It is reasonable to delay history indicated transvaginal cerclage until the results of first-trimester screening are available. However, this should be an individualized decision with the patient aware that suture removal would be required in the case of a miscarriage or decision for termination of pregnancy. Viability (presence of fetal heart) should be confirmed prior to insertion of the cerclage. Women should be counseled as to a small risk of miscarriage unrelated to the cerclage (less than 1% at 14 weeks' gestation).16

Decision making regarding type of transvaginal cerclage

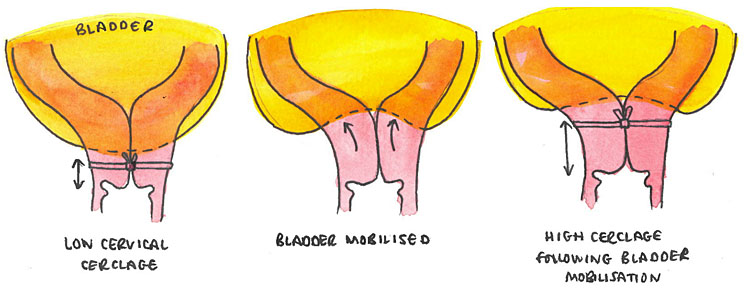

A high vaginal suture needing bladder dissection may be required when the vaginal portion of the cervix is insufficient. The skills needed to perform a high transvaginal cerclage are greater to those required to perform a low cerclage. The need for bladder reflection can be assessed by vaginal examination in clinic to ensure an appropriately skilled surgeon is available on the day of surgery. Figure 1 demonstrates the difference in position of cerclage for low versus high transvaginal cerclages.

Decision making surrounding emergency cerclage is discussed later in this chapter.

1

Bladder mobilization to achieve high transvaginal cerclage.

Cerclage material

There is currently little direct clinical evidence favoring a monofilament or braided suture in the placement of a transvaginal cerclage. The C-STITCH trial, which compares these two methods, is due to report.17 There is evidence that the use of monofilament is associated with less disruption to the microbiome than braided suture, but it is unclear if this confers any clinical advantage.18

Consenting for cervical cerclage

Wherever practically possible, women should be consented in clinic prior to their procedure and given time to consider the risks of the procedure and ask any further questions. Table 3 details risks associated with cerclage types. Adverse effects are rare, and the vast majority of cerclages uncomplicated. Complications associated with pregnancy loss are greater. Although cerclage reduces the risk of miscarriage and early preterm birth, it can fail, and women should be aware of this.

General risks | Specific to abdominal | Specific to emergency |

Damage to bladder | Damage to abdominal structures | PPROM at time of procedure |

Cervical trauma | Need for CS for delivery | Chorioamnionitis |

Bleeding | ||

Cervical laceration if spontaneous labor with cerclage in situ | ||

Preterm cervical shortening despite cerclage | ||

Need for regional anesthesia for removal (Shirodkar) |

Anesthetic considerations

Safety has been demonstrated with both regional and general anesthesia for cervical cerclage. Generally regional anesthesia is safer for the mother and general anesthesia confers no technical advantage to the procedure. Pre-operative discussion between the anesthetist and the patient should take place and should encompass risks of both types to the pregnant woman as well as her preference.

PERFORMING TRANSVAGINAL CERVICAL CERCLAGE

Low transvaginal cerclage

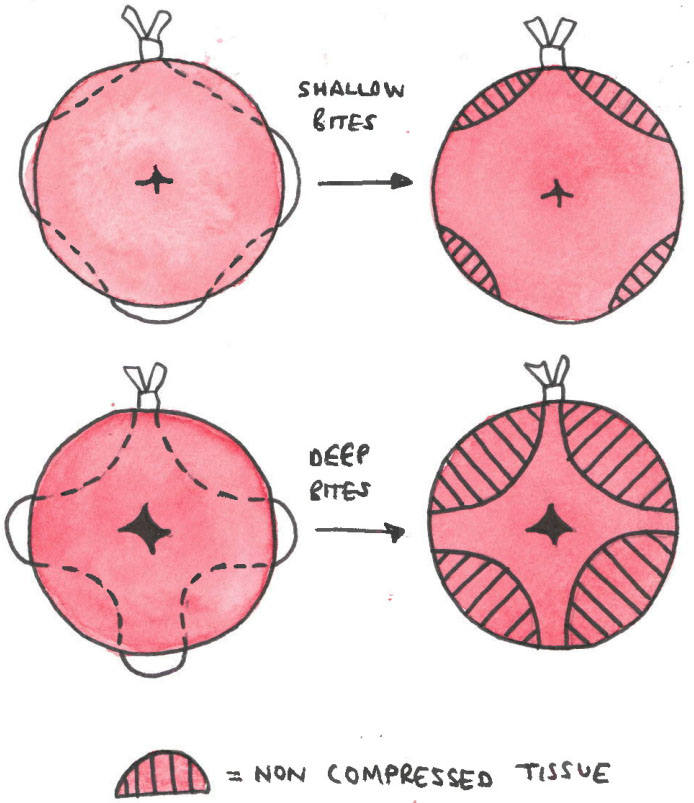

With the patient in lithotomy, the perineum and vagina should be cleaned, preferably using aqueous chlorhexine solution (thought to be less caustic to mucous membranes then iodine-based preparations), surgical drapes applied, and the patient examined under anesthesia. Using a combination of Sims’ speculums and lateral wall retractors, the cervix can be visualized and stabilized using atraumatic instruments such as sponge-holders. With the general aim of achieving a cerclage as high as possible while avoiding the bladder, a purse string cerclage is inserted using the technique demonstrated in Figure 2. Knots can be tied anteriorly for ease of access at time of removal, but the exact location of the knots and whether a loop has been tied should be documented clearly. Hemostasis is then confirmed and instruments removed. Shallow bites may lead to cervical change still occurring with membrane prolapse within the suture and deep bites may lead to the suture cutting through and failure (see Figure 2). Shallow bites are generally needed with ultrasound indicated cerclage to prevent inadvertent membrane trauma during the procedure.

Depending on the anesthetic used, an in–out or indwelling catheter should be sited and it should be confirmed that the urine is clear.

2

Purse-string suture.

High transvaginal cerclage

Patients should be considered at higher risk for needing high transvaginal cerclage if they have had previous cervical surgery, particularly cone biopsies or multiple LLETZ procedures. The decision for high transvaginal cerclage is individualized but should be considered where an experienced operator believes they are unlikely to achieve a sufficiently high cerclage without bladder mobilization.

The procedure will commence similarly to the low cerclage up to the point of the examination under anesthesia and positioning of retractors. Forceps with smaller jaws, such as a Babcock’s, can be used in place of sponge holders where there is less tissue to grasp. The bladder should then be identified to avoid trauma. This can be done digitally, or where there is an element of uncertainty, a catheter can be placed in the bladder and the lowest point an inflated balloon can be palpated can be taken to be the lower edge. The cervix is then incised anteriorly to create a plane that allows for bladder mobilization cranially. This creates length to the cervix in which a cerclage can be sited as described above. The incision can then be closed using vicryl rapide 2–0, but leaving the cervical cerclage knots and loops visible centrally. Hemostasis is confirmed, remaining instruments removed, and catheterization undertaken.

If there is any suspicion of a major bladder injury intraoperatively this should be explored and repaired, with a plan made for prolonged catheterization and follow-up.

The patient should be informed that this cerclage may require regional anesthesia for removal.

Emergency cerclage with exposed membranes

Perioperative decision making

The decision to undertake emergency cerclage is one that should only be made after thorough assessment of the patient and detailed discussion regarding the risks of undiagnosed chorioamnionitis in the mother and extreme prematurity (with or without chorioamnionitis) in the baby.19

Emergency cerclage has a high risk of procedure failure: both at the time of surgery via PPROM, and the likelihood of delivery prior to viability, or at the border of viability. The patient should be appropriately counseled. Factors such as cervical dilatation at the time of diagnosis, any cervical change thereafter, presence of sludge in the amniotic fluid, visibility of fetal parts and pre-existing risk factors for second-trimester loss should be considered but are not an absolute contraindication to cerclage. There is a role for fetal fibronectin if available, with a small study demonstrating that it can be used to predict latency to delivery in women with exposed membranes.20 It may be considered necessary to involve neonatologists in discussion regarding this cerclage.

Careful assessment for infection should be undertaken, such as maternal white-cell count and C-reactive protein, but clinicians should be aware that these can be normal in cases of evolving chorioamnionitis.21 Even where there is no clinical evidence of chorioamnionitis other than preterm cervical dilatation, clinicians should advise women that this is a possible evolving picture and that the cerclage would need to be removed should she become septic. Some clinicians advocate for routine amniocentesis prior to emergency cerclage to further investigate for chorioamnionitis,22 although this does not have a strong evidence base. Nonetheless it may be preferred by some patients and clinicians owing to the high risk of cerclage failure and increased risk of maternal deterioration if subclinical infection is present. If a clinician and patient do decide to proceed with pre-procedure amniocentesis then the patient should be informed that this does not seem to increase the risk of delivery prior to 28 weeks although evidence is scant.

Other peri-operative interventions such as genital tract screening and amnioreduction should not be routinely offered, although noted infections should be treated. Prophylactic perioperative tocolysis should not be offered, and women requiring treatment tocolysis should not be offered a cerclage.

Women should be informed that the procedure will be abandoned if examination under anesthesia reveals that it is no longer technically possible.

Placement of emergency cerclage

If a woman is having an emergency cerclage under regional anesthesia it would be reasonable to allow a partner to be with her given the high risk of serious intraoperative complications, and the anxiety that is to be expected the woman might feel.

Emergency cerclage should be undertaken by an experienced clinician. The patient should be cleaned and draped as per other vaginal cerclages. Retractors can be used similarly to improve visualization of the cervix. Assuming that the cerclage is going ahead, protection of the fetal membranes is usually required. This can be achieved with a combination of the following:

- Trendelenburg with lithotomy to allow membranes to fall cranially

- Insertion of a Foley’s catheter to the cervical os and inflation of the balloon to push membranes cranially

- Use of a damp swab on a stick to push membranes cranially

The final two options also provide a barrier between the needle and the fetal membranes.

There is currently no evidence-based preference for suture type, but monofilament may be easier to insert into an effaced cervix. How the suture is placed (purse-string or anterior-posterior) would be determined intraoperatively and must be clearly documented. A randomized controlled trial into emergency cerclage with an observational arm is currently recruiting in the UK.23

Occlusion suture

Occlusion suture is performed by resecting the cervical epithelium and glandular epithelium using a high-revolution rotating device, then passing 2–3 inner circular sutures to close the cervical canal, and finally two rows of sutures to close the external os. There is no high-quality evidence supporting this practise as an adjunct or primary intervention and it should not be routinely carried out.24 There is concern that interfering with the cervical canal will increases the risk of ascending infection.

POST-OPERATIVE CARE

Routine post-operative care

Prior to surgery, women should be counseled on the post-operative period, particularly in terms of expected duration in hospital and care following discharge.

In the case of women having history or ultrasound indicated transvaginal cerclage, it is reasonable for this to be done as a day case with an aim for the patient to be discharged once recovered from the anesthetic and passing urine. Women should be informed that reduction in length of hospital admission is likely to reduce their risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) and nosocomial infection without augmenting the risk of preterm delivery or second-trimester pregnancy loss.

Care following emergency cerclage

Women who have undergone emergency cerclage are likely to require a more protracted hospital admission given the high risk of second trimester loss or delivery at periviability.

The care of these women should be managed by a multidisciplinary team that includes obstetricians, midwives, anesthetists, and neonatologists as a minimum. The following should be planned and, after discussion with the women and someone supporting her, be clearly documented:

- Gestation at which neonatal resuscitation will be considered

- Indications for cerclage removal

- Earliest gestation steroids and magnesium sulphate should be considered, and indications for commencing these

- Criteria for discharge to outpatient follow-up if pregnancy continues

Follow-up care

For many women, cervical length scanning is not required after cerclage. However, it may be useful in some cases of ultrasound indicated or emergency cerclage to aid with planning of ongoing care like hospital admission or steroids. Cervical lengths can be relied upon. Women requesting cervical length scanning for reassurance after cerclage should be informed that this is unlikely to give any additional information about their pregnancy.

Fetal fibronectin is valid in women with cerclage in situ.25,26 Although its routine use is limited, it should be used in symptomatic women in the same way as for women who do not have cerclage. Its high negative predictive value should be made clear to women who have low results. Other tests available to predict spontaneous preterm birth, such as Actim Partus or Partosure, have not published data in the cerclage population.

Adjunct Care

Tocolysis

It has been theorized that cerclage insertion could precipitate uterine activity and so tocolysis should be given prophylactically. While some studies evaluating cerclage have used perioperative tocolysis (usually indomethacin), none have compared their results to a group without it. However, one study has shown perioperative indomethacin has no effect on outcome among women undergoing cerclage.27 It is not routinely recommended.

Progesterone and cerclage

There is currently no evidence that giving progesterone following history or ultrasound indicated cerclage prolongs pregnancy or improves neonatal outcomes. While one small study suggests that progesterone at the time of emergency cerclage does increase latency to delivery and improve neonatal outcomes,28 a systematic review and meta-analysis showed no reduction in delivery prior to 34 weeks when combining methods.29

In women who are already on progesterone (either as an initial treatment in the prevention of preterm birth, or as part of assisted conception care) an individualized care plan should be agreed with the women regarding timing of discontinuation. The dose should be noted as those given as part of assisted conception regimens is often far in excess of that required in the prevention of preterm birth, so can likely be at least reduced if not stopped entirely.

Sexual intercourse

There is no evidence that abstinence decreases rates of preterm birth, or that sexual activity increases the risk. Women should not be advised to abstain from sex to reduce their risk.

Bed rest

There is no evidence that bed rest decreases rates of preterm birth,30 although it might be reasonable to discuss it in individual cases (such as bulging membranes). Discussion regarding bed rest should take into account the potential health risks (such as deep vein thrombosis), emotional strain, and financial implications. Bed rest in hospital also has health economic implications and these should be considered when designing policy around this intervention.

TIMING AND MODE OF DELIVERY

Neither timing nor mode of delivery should be dictated by the presence of a transvaginal cerclage. Unless there is an obstetric indication for earlier delivery, suture removal at 37 weeks is reasonable as preterm delivery has been avoided and there is no risk of cervical trauma from laboring with the cerclage in situ. In the cases of low sutures this is usually achievable using a speculum only and offering simple analgesia pre-procedure, and Entonox during removal. If a high cerclage has been sited then regional anesthesia may be required for removal, although it would be reasonable to examine a patient in the room to confirm this. If an elective cesarean section is the planned mode of delivery, it is reasonable to perform the cerclage removal at the time of delivery.

Labor does not need to be induced except for another obstetric reason. Transvaginal cerclage is not an indication for cesarean section. However, women who have had previous cervical surgery (such as LLETZ or cone biopsy) should be informed of the small risk of cervical stenosis and this should be considered early as a cause of labor dystocia if there is a prolonged latent phase or minimal effect with prostaglandins.

Transvaginal cerclage should be removed prematurely in the following circumstances:

- Active labor

- Active vaginal bleeding

- Evidence of chorioamnionitis

- Other obstetric indication for early delivery

In the case of PPROM it may be reasonable to leave the cerclage in situ at least for steroid maturity to be reached, or until there is other evidence of either labor or chorioamnionitis,31 but this decision should be made by senior clinicians in conjunction with the patient and neonatologists.

TRANSABDOMINAL CERCLAGE

Preoperative considerations

Transabdominal cerclage can be sited prepregnancy or in the first trimester. Prepregnancy transabdominal cerclage does not decrease the chance of conception.32 The decision to wait for screening results to become available before an antenatal transabdominal cerclage is placed needs to be weighed against the increasing size and vascularity of the uterus as the pregnancy continues, both of which make placement increasingly challenging. First-trimester miscarriage and termination of pregnancy can both be managed surgically without cerclage removal, which can be left for future pregnancies.

Transabdominal cerclage has been demonstrated to reduce delivery prior to 32 weeks as compared to vaginal cerclage (high or low) in women with previous failed vaginal cerclage (8% in transabdominal group, versus 33% in transvaginal group). The same study showed a reduction in fetal loss between the two groups (3% in transabdominal group, versus 21% in transvaginal group).4

Performing transabdominal cerclage

Transabdominal cervical cerclage should be performed in the absence of a vaginal cervix or where transvaginal history or ultrasound indicated cervical cerclage has failed (i.e., delivery before 28 weeks' gestation following history or ultrasound indicated cerclage). Transabdominal cerclage can be performed laparoscopically or via a transverse laparotomy. Both are equally efficacious.33 Laparoscopic procedures will take longer and increase the overall abdominal scarring as these women will have a cesarean section to deliver. Surgical expertise and patient preference should be considered prior to decision making. It should also be noted whether the patient is at very high risk of dense adhesions, e.g., post pelvic radiation or multiple laparotomies.

In preparation for either procedure, the patient should be catheterized, cleaned, and draped. If it is confirmed, or there is suspicion, that the patient is pregnant then uterine manipulators should not be used as part of the laparoscopic procedure.

If taking an open approach, it is reasonable to cut a mini transverse laparotomy, given that delivery will be via cesarean section. Laparoscopy should be achievable with a laparoscope and two accessory ports.

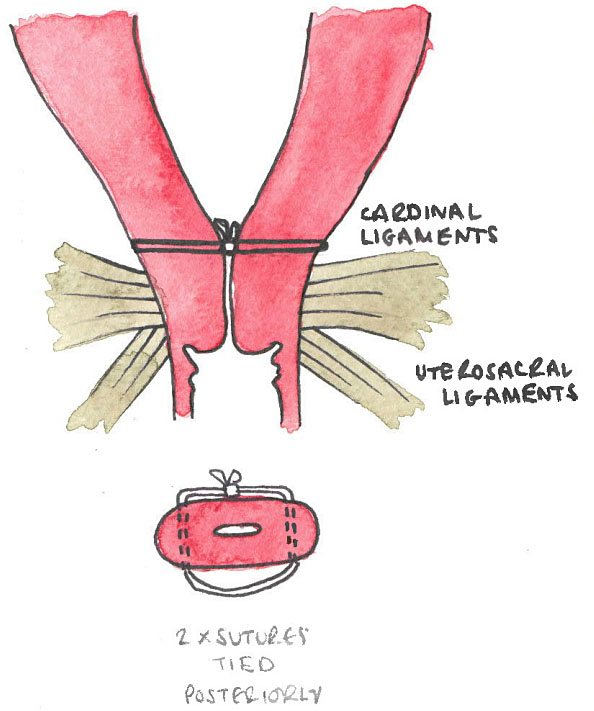

In either case, once the uterus is accessed, the uterovescical fold opened and the bladder reflected caudally. The suture should be sited superior to the uterosacral and cardinal ligaments, lateral to the cervical vessels (Figure 3). Like transvaginal cerclage, there is no recommendation for monofilament or braided suture. When taking a laparoscopic approach, straight needles tend to be used; at laparotomy curved needles may prove easier from a surgical point of view. Knots should be tied posteriorly to reduce bladder irritation and to allow for posterior colpotomy, which will be discussed later in the chapter. A video of both procedures is available.34

3

Transabdominal cerclage demonstrating the height of cerclage as compared to the cardinal and uterosacral ligaments and the posterior placement of the knots.

Postoperative care

Women who have had transabdominal cerclage do not need prolonged hospital stay. Post-operative care, in particular analgesia and nutrition, should be targeted towards early mobilization. VTE prophylaxis should be considered.

Management of pregnancy loss in women with transabdominal cerclage

In the case of pregnancy loss following transvaginal cerclage, the cerclage can be removed to facilitate delivery. However, in transabdominal cerclage decision-making is somewhat more complex and depends on a number of factors including gestation at pregnancy loss, desire for future pregnancy, available expertise, and urgency of delivery. Patients in this situation should be managed by experienced, senior clinicians given the complexity of decision-making and likelihood of difficult surgery.

In the first trimester surgical and medical management of miscarriage or termination of pregnancy can be undertaken through the cerclage. Up to 14 weeks' gestation, surgical evacuation can be completed through the cerclage. A dilatation and evacuation can be performed after 14 weeks in suitably skilled clinicians.35 Beyond 18 weeks the cerclage can be removed via posterior colpotomy to facilitate vaginal delivery,36 or if this is not possible, hysterotomy performed. Women should be informed of the risks of hysterotomy to future pregnancy beyond the risks of a repeat cerclage insertion following colpotomy and removal of suture (namely scar dehiscence and uterine rupture).

Unless clinical emergency dictates otherwise, women should be as involved in decision making as they wish to be. They should also have access to bereavement care and emotional support wherever possible.

Timing of delivery

Patients with transabdominal cerclage are delivered by cesarean section as the cervix cannot dilate owing to the presence of the permanent suture and so labor would obstruct and ultimately result in uterine rupture. The timing of the cesarean section should not be dictated by the cerclage, and preterm or early term delivery for other obstetric indication can be performed as usual. Elective cesarean should be planned after 38 weeks.

Cesarean section is routine with abdominal cerclage except that the position and integrity of the cerclage can be reviewed. If the patient is certain that she has no plans to conceive again it could be removed by exteriorizing the uterus and cutting the sutures posteriorly. There is no evidence of harm if it is left in place.

EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES

Cerclage simulator models

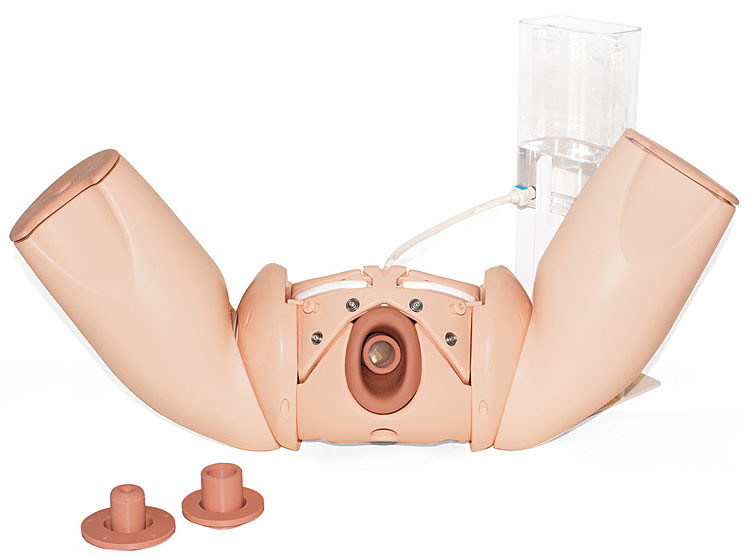

Cervical cerclage simulator models have recently been evaluated (Figure 4) and have been demonstrated to increase confidence among doctors learning how to place cerclage. Use of a simulator increases opportunity to teach both in terms of ability to repeat steps and practice skills, but also for free conversation given that when operating with patients under regional anesthesia conversation can sometimes be inhibited. Furthermore, it provides a no consequence environment for novices to practise the entire procedure before performing it on a patient, and for experts to refine technique or attempt a new one.

4

Cervical cerclage simulator demonstrating cervix with exposed membranes. Reproduced courtesy of Limbs & Things.

CONCLUSION

The pathophysiology of cervical change is complex with multiple risk factors for preterm change identified. The benefit of cervical cerclage in the prevention of spontaneous preterm birth has been demonstrated where the identified risk factor is previous second-trimester loss or preterm birth, but is less clear when other risk factors are demonstrated. Techniques and timing of cerclage vary and can be individualized to the patient.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- Women should be managed in an individualized way with consideration given to their specific risk factors for preterm birth

- Transvaginal cervical cerclage should be offered to all women with three or more mid trimester/spontaneous preterm losses

- Transabdominal cerclage should be offered electively to all women who have a history of a failed transvaginal cerclage

- Ultrasound indicated cerclage should be considered in women with a singleton pregnancy and risk factors for preterm birth, if the cervix is <25 mm. However, women should be counseled that evidence for this based on risk factors other than previous preterm delivery is lacking

- In women with a multiple pregnancy, consideration should be given to cerclage if the cervix is <15 mm

- Women who are being considered for emergency cerclage with exposed membranes should be informed that evidence for this procedure is lacking, and that where there is subclinical chorioamnionitis, cerclage could complicate the pregnancy further

- In the absence of obstetric complications, transvaginal cerclage can be removed at 37/40 and spontaneous onset labor awaited

- Transabdominal cerclage necessitates delivery by cesarean section and this can be planned after 38 weeks' gestation in the absence of other obstetric complications

- In women with transabdominal cerclage pregnancy loss or termination up to 14 weeks should be managed routinely. Management of pregnancy loss or termination after this point should be managed by an experienced expert.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks to Hannah Rosen O’Sullivan for illustrations.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Author(s) statement awaited.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

FREELY AVAILABLE RESOURCES

- Transabdominal cervical cerclage via laparotomy and laparoscopy training video: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2589933320302068?via%3Dihub#appsec1

- FIGO Good Practice Recommendations on Progestogens for Prevention of Preterm Delivery https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ijgo.13852

- FIGO Good Practice Recommendations on Cervical Cerclage for the Prevention of Preterm Birth https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ijgo.13835

- FIGO Good Practice Recommendations on the use of pessary for reducing the frequency and improving outcomes of preterm birth https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ijgo.13837

- FIGO Good practice Recommendations on Magnesium Sulphate Administration for Preterm Fetal Neuroprotection https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ijgo.13856

- FIGO Good Practice Recommendations on the Use of Prenatal Corticosteroids to Improve Outcomes and Minimize Harm in Babies Born Preterm https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ijgo.13836

- NICE Guideline on Preterm Labor and Birth https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng25/resources/preterm-labour-and-birth-pdf-1837333576645

- UK Preterm Clinical Network Guideline: Reducing Preterm Birth – Guideline for Commissioners and Providers tommys.org/sites/default/files/2021–03/reducing%20preterm%20birth%20guidance%2019.pdf

REFERENCES

Alfirevic Z, Stampaliga T, Medley N. Cervical stitch for preventing preterm birth in singleton pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2017;6:CD008991. | |

MRC/RCOG Working party on Cervical Cerclage. Final report of the Medical Research Council/Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists multicentre randomised trial of cervical cerclage. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1993;100(6):516–23. | |

Davenport SM, Jackson AL, Herzog TJ. Cerclage during trachelectomy for early-stage cervical cancer. Gynecologic Oncology 2016;141:2–208. | |

Shennan A, Chandirimani M, Bennett P, et al. MAVRIC: A multicentre randomised controlled trial of transabdominal versus transvaginal cervical cerclage. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2020;222(3):261e.1–9. | |

UK Preterm Birth Clinical Network. Reducing preterm birth: Guideline for Commissioners and Providers, 2019. | |

Owen J, Hankins G. Iams JD, et al. Multicentre randomized trial of cerclage for preterm birth prevention in high-risk women with shortened midtrimester cervical length. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2009;201(4):375:e1–8. | |

Simcox R, Seed PT, Bennett P, et al. A randomised controlled trial of cervical scanning versus history to determine cerclage in women at high risk of preterm birth (CIRCLE trial). American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2009;200(6):623.e1–6. | |

Bergella V, Baxter JK, Hendrix NW. Cervical assessment by ultrasound for preventing preterm delivery. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013;1:CD007235. | |

Vousden N, Hezelgrave N, Carter J, et al. Prior ultrasound indicated cerclage: how should we manage the next pregnancy. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 2015;188:129–32. | |

Rafael TJ, Berghella V, Alfirevic Z, et al. Cervical stitch for preventing preterm birth in multiple pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014:CD009166. | |

Jarde A, Lutsiv O, Park CK, et al. Preterm birth prevention in twin pregnancies with progesterone, pessary or cerclage: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2017;124(8):1163–73. | |

Roman A, Rochelson B, Fox NS, et al. Efficancy of ultrasound-indicated cerclage in twin pregnancies. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2015;212(6):788:e1–6. | |

Shennan A, Suff N, Leigh Simpson J, Jacobssen B, Mol BW, Grobman WA for the FIGO Working Group on Preterm Birth. FIGO Good practice recommendations on progestogens for prevention of preterm delivery. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics 2021;155(1):16–8. | |

Grobman WA, Normal J, Jacobsson B for the FIGO Working Group for Preterm Birth. FIGO Good practice recommendations on the use of pessary for reducing the frequency and improving outcomes of preterm birth. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics 2021;155(1):23–5. | |

Hezelgrave NL, Watson HA, Ridout A, et al. Rationale and design of SuPPoRT: a multi-centre randomised controlled trial to compare three treatments: cervical cerclage, cervical pessary and vaginal progesterone, for the prevention of preterm birth in women who develop a short cervix. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016;16(1):358. | |

Zauche LH, Wallace B, Smoots AB, Olson CK, Odeyebo T, Kim SY, Petersen EE, Ju J, Beauregard J, Wilcox AJ, Rose CE, Meaney-Delman DM, Ellington SR for the CDC v-safe Covid-19 Pregnancy Registry Team. Receipt of mRNA Covid-19 vaccines and risk of spontaneous abortion. New England Journal of Medicine 2021;385(16):1533–5. | |

Israfil-Bayli F, Morton VH, Hewitt CA, et al. C-STITCH: Cerclage suture type for an insufficient cervix and its effect on health outcomes – a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Trials 2021;22(1):664. | |

Kindinger LM, MacIntyre DA, Lee YS, et al. Relationship between vaginal microbial dysbiosis, inflammation and pregnancy outcomes in cervical cerclage. Science Translational Medicine 2016;8(350):350ra102. | |

Wierzvhowska-Opoka M, Kimber-Trojnar Z, Leszczynska-Gorzelak B. Emergency cervical cerclage. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2021;10(6):1270. | |

Suff N, Hall M, Shennan A, et al. The use of quantitative fetal fibronectin for the prediction of preterm birth in women with exposed fetal membranes undergoing emergency cervical cerclage. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 2020;246:19–22. | |

Wiwanitkit V. Maternal C-reactive protein for detection of chorioamnionitis: an appraisal. Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics and Gynecology 2005;13(3):179–81. | |

Lee SE, Romero R, Park CW, et al. The frequency and significance of intraamniotic inflammation in patients with cervical insufficiency. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2008;198(6):633e.1–8. | |

Hodgetts-Morton V, Hewitt CA, Jones L, et al. C-STITCH2: Emergency cervical cerclage to prevent miscarriage and preterm birth – study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2021;22(1):529. | |

Brix N, Secher NJ, McCormack C, Helmig RB, H Hein M, Weber T, Mittal S, Kurdi W, Palacio M, Henriksen TB, on behalf of the CERVO group. Randomised trial of cervical cerclage, with and without occlusion, for the prevention of preterm birth in women suspected for cervical insufficiency. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2013;120(5):613–20. | |

Duhig KE, Chandirimani M, Seed PT, et al.Fetal fibronectin as a predictor of spontaneous preterm labour in asymptomatic women with cervical cerclage. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2009;116(6):799–803. | |

Smout E, Abbot D, Tezcan B, et al. The use of fetal fibronectin in women with rescue cervical cerclage. Archives of Disease in Childhood – Fetal and Neonatal Edition 2011;96:Fa63–4. | |

Visintine J, Airoldi J, Berghella V. Indomethacin administration at the time of ultrasound indicated cerclage: is there an association with a reduction in spontaneous preterm birth? American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2008;198(6):643.e1–3. | |

Ragab A, Mesbah Y. To do or not do emergency cervical cerclage (a rescue stitch) at 24–28 weeks gestation in addition to progesterone for patients coming early in labour? A prospective randomised trial for efficancy and safety. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics 2015;292(6):1255–60. | |

Jarde A, Lewis-Mikhael AM, Dodd JM, et al. The more the better? Combining interventions to prevent preterm birth in women at risk – a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of Canada 2017;39(12):1192–1202. | |

Sosa CG, Althabe F, Belizan JM, et al. Bed rest in singleton pregnancies for preventing preterm birth. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015;3:CD003581. | |

Suff N, Kunitsyna M, Shennan A, et al. Optimal timing of cervical cerclage removal following preterm premature rupture of membranes: a retrospective analysis. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Health 2021;259:75–80. | |

Vousden NJ, Carter J, Seed PT, et al. What is the impact of preconception abdominal cerclage on fertility: evidence from a randomised controlled trial. Acta Obsterica Gynecologia Scandinavia 2017;96(5):543–6. | |

Tulandi T, Alghanaim N, Hakeem G, et al. Pre and post-conceptional abdominal cerclage by laparoscopy or laparotomy. Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology 2014;21(6):987–93. | |

Suff N, Khurt K, Chandirimani M, et al. Development of a video to teach clinicians how to perform transabdominal cerclage. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology: Maternal Fetal Medicine 2020;2(4):100238. | |

Dethier D, Lassey SC, Pilliod R, et al. Uterine evacuation in the setting of transabdominal cerclage. Contraception 2020;101(3):174–7. | |

Burger NB, van Hof EM, Huirne JAF. Removal of an abdominal cerclage by colpotomy: a novel and minimally invasive technique. Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology 2020;27(7):1636–9. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards program CLICK HERE)