This chapter should be cited as follows:

Paterson P, Simas C, et al., Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.418083

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Obstetrics Module

Volume 17

Maternal immunization

Volume Editors:

Professor Asma Khalil, The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, London, UK; Fetal Medicine Unit, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, St George’s University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK

Professor Flor M Munoz, Baylor College of Medicine, TX, USA

Professor Ajoke Sobanjo-ter Meulen, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

Chapter

Coverage and Acceptance of Maternal Vaccines. Challenges and Opportunities in Low- and Middle-Income Countries vs. High-Income Countries

First published: May 2023

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

In 2012, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended vaccination in pregnancy against a number of vaccine preventable diseases with the aim of reducing maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality globally, by protecting the pregnant woman herself and also providing passive immunity to the infant following birth.1,2 The WHO position papers advise that all countries globally consider including three antenatal vaccines into their national immunization schedules. This includes influenza vaccination, combined tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap), and tetanus vaccination for high-risk areas.1,3,4 The 2012 WHO influenza position paper identified pregnant women as the highest priority group, recommending universal seasonal inactivated influenza vaccination of all eligible women.1 The widespread administration of maternal tetanus toxoid vaccination through national immunization programs has contributed to an estimated 90% reduction in the global burden of deaths due to neonatal tetanus from 199,118 in 1990 to 19,937 in 2015.5

However, despite the WHO recommendation for the inactivated influenza, combined tetanus, diphtheria and pertussis (Tdap) and the tetanus toxoid vaccines for pregnant women, coverage of maternal influenza vaccination, in particular, remains well below national targets.2,6 Apart from the tetanus vaccination program, maternal vaccination for pertussis and influenza appear to be historically less accepted. In countries (for example, the UK and USA) where health experts recommend pertussis and/or influenza vaccination, and the uptake is monitored, we have seen the coverage is inadequate.7,8,9

The UK coverage of pregnant women with seasonal influenza from 1 September 2020 to 28 February 2021 was 43.6%.8 In the UK, uptake of the prenatal pertussis vaccination from October to December 2022 ranged from 32.0 to 82.6% with London representing one of the lowest coverage regions 32.0–55.5%.9 Many European countries have introduced maternal vaccination recommendations, yet the coverage remains inadequate due to implementation challenges and low public acceptability.10,11 Many countries have no accurate national data of maternal vaccination uptake.12 As of January 2018, in Australia there is no available country-wide uptake data for maternal immunization.12 A review of the more regional data suggests coverage was between 7–40% for antenatal influenza vaccination between 2010–2014.12

The reasons underlying low maternal vaccination acceptance despite national recommendations are complex and vary by context and population.13 Demographic characteristics such as younger age, having less than a university education, being unmarried, not having health insurance, and having a history of pre-term delivery were associated with a lower uptake of maternal seasonal and pandemic influenza vaccination in the USA and Canada.14,15,16 Women’s perceptions of disease severity and susceptibility are also known to influence maternal vaccination acceptance; concerns about the severity of pertussis were associated with a higher pertussis vaccination uptake among pregnant women in Germany, whereas a perception of low susceptibility to influenza or pertussis was associated with decreased vaccination uptake among pregnant women in the USA, Taiwan, and South Korea.17,18,19,20 Vaccine hesitancy, generally taking the form of concerns about the safety, efficacy, and need for maternal vaccines, are a commonly cited barrier to vaccination during pregnancy globally.13 In contrast, a strong recommendation or offer of vaccination by a healthcare provider, adequate knowledge about vaccines, and having a desire to protect the fetus or oneself from diseases are important facilitators of maternal vaccination globally.21

The WHO recommends vaccination in pregnant women who are either at high risk of exposure to Covid-19, or have comorbidities that place them in a high-risk group for severe Covid-19.22 As with other vaccines, again uptake in these pregnant women is sub-optimal. Country estimates of Covid-19 vaccine uptake in pregnant women are rare.

METHODOLOGY

To understand why uptake is low despite recommendations, our Vaccine Confidence ProjectTM research team conducted a multi-methods study to explore experiences and views towards vaccinating in pregnancy and participating in maternal vaccine trials among pregnant and recently pregnant women globally.

The study population consisted of pregnant and recently pregnant women in 15 countries (Australia, Brazil, Canada, France, Germany, India, Italy, Korea, Mexico, Panama, South Africa, Spain, Taiwan, the UK, and the USA). These countries were chosen given the diversity in historical, cultural, and geographic domains. Data was collected in collaboration with WIN/Gallup International Association (WIN/GIA).

Between December 2018–January 2019, WIN/GIA conducted 500 survey questionnaires (approximately 15 min each) with women who were pregnant or who had a child in the previous year (i.e., child under 2 years old) in each of the 15 countries (a total of 7500 surveys). The survey questions were developed by the Vaccine Confidence Project with WIN/GIA, based on the Vaccine Confidence IndexTM (VCI) successfully deployed in previous global surveys and other questionnaires conducted on vaccine hesitancy. The survey questions covered socio-economic variables and questions on vaccine confidence, experiences, and views. A nationally representative sample was surveyed in each country. The method by which pregnant and recently pregnant women were surveyed varied depending on the country (face to face, over the phone, or online). The surveys were conducted in local languages and translated to English for the analysis. When a representative sample was not available, the survey data was weighted to account for over- or under-sampling of particular socio-economic groups. Between December 2020–January 2021 we conducted a second wave of the global survey, as well as a sub-national survey in India, and added additional questions to our survey about the willingness of pregnant women to accept current and future vaccines, including a novel Covid-19 or RSV vaccine.

In-depth interviews were carried out with approximately 20 pregnant women in each country between February and May 2019. Pregnant women were purposively selected to include a mix of those who indicated willingness to accept the vaccine during pregnancy and/or participate in the trial as well as those who indicated reluctance or unwillingness to vaccinate during pregnancy. Four focus group discussions were conducted across two main cities in each of the countries (two focus groups in each of the two cities per country) between February and May 2019. Groups were split into first time pregnancies, and a second group of new mothers and women who have been pregnant one or more times previously. The topic guides were developed to collect data on awareness, experiences, views, attitudes, and decision-making factors influencing vaccination in pregnancy, as well as awareness of maternal vaccine trials and views about participating in such trials. The topic guides were translated into the main local languages, and a translator was present when necessary.

Social media data was monitored using Pulsar®, a media intelligence system, which sources media content from a wide range of digital and social media outlets worldwide. Data for this study was collected from Twitter, Facebook public groups, blogs, public forums, Reddit, and YouTube between November 2018 and October 2019, and consisted of original posts and engagements with those posts (e.g., a retweet, a share, or a comment).23

VACCINE AWARENESS AND UPTAKE

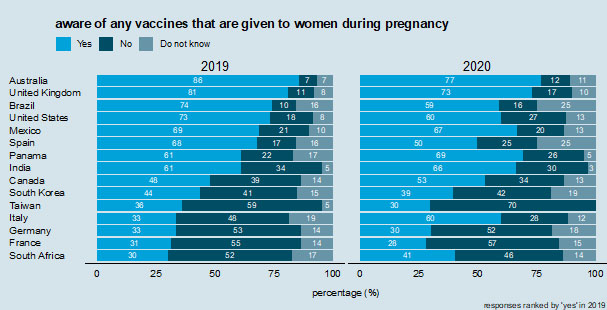

In 2020, slightly over half (53%) of the women surveyed reported being aware of vaccines being given during pregnancy, slightly lower than the percentage aware in 2019 (56%). In 2020, awareness of vaccines to be given during pregnancy was the highest in Australia (77%) and the UK (73%): these countries also had the highest awareness in 2019 (Figure 1). In 2019, eight of the 15 countries surveyed had a majority of respondents who reported they were aware of vaccines being given to women during pregnancy. In 2020, this increased to nine out of 14 (Figure 1). However, despite this increase in the number of countries reporting high awareness of vaccines in 2020, in ten countries there were lower proportions of women surveyed who reported being aware of vaccines during pregnancy compared to 2019: Australia, Brazil, France, Germany, Mexico, South Korea, Spain, Taiwan, the UK, and the USA (Figure 1). In the interviews and focus groups, pregnant women in France – especially new mothers – reported high frequencies of contact with doctors/medical professionals but reported relatively low awareness of maternal vaccination. This suggests that these contact points are not being used as effectively as possible.

Of the countries surveyed, the largest increase in the proportion of respondents surveyed who reported being aware of vaccines during pregnancy is in Italy, with 33% aware in 2019 compared to 60% in 2020 (Figure 1).

1

Awareness of vaccines from the question "are you aware of any vaccines that are given to women during pregnancy?"

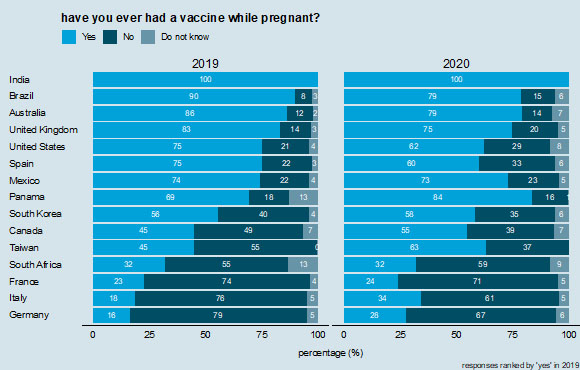

Across the 15 countries, the average proportion of women who reported they had ever been vaccinated while pregnant is 58%; India (100%), Brazil (90%), and Australia (86%) had the largest proportion of women surveyed who stated that they had previously received a maternal vaccination. France (23%), Italy (18%), and Germany (16%) had the lowest proportion of women who reported ever receiving a maternal vaccination. In 2019 a large proportion (80%) of women in India were aware of the tetanus vaccine, but considerably fewer were aware of the influenza (24%) and pertussis/whooping cough (15%) vaccines, possibly due to the fact that only tetanus was nationally recommended during pregnancy then. National recommendations for vaccination during pregnancy are known to carry weight in maternal vaccination decision-making and are important to publicize to improve awareness and trust in vaccines.21,24

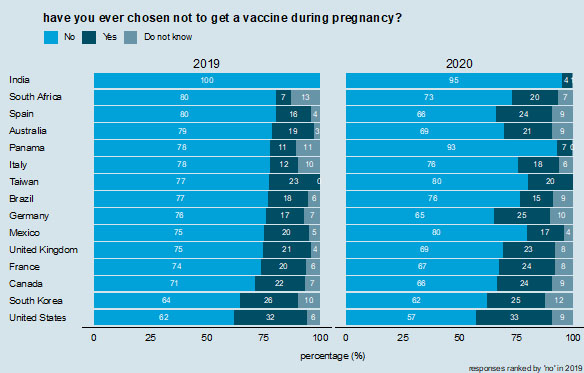

In most countries, a majority of respondents reported having had a vaccine while pregnant. However, there is considerable variability across nations. While 100% of respondents in India report having had a vaccine during pregnancy, only 24% in France, 28% in Germany, 32% in South Africa, and 34% in Italy report in 2020 having been vaccinated during pregnancy (Figure 2). There is far less variability in whether respondents have ever deliberately chosen to not vaccinate during pregnancy (Figure 3). In 2020, roughly one in five respondents in every country except India (4%) have chosen to not receive a vaccine during pregnancy, with values ranging 15% in Brazil to 25% in Germany, but with most values in the low 20% (Figure 3). These values are comparable to the percentages who report choosing not to receive a vaccine during pregnancy in 2019 (Figure 3).

2

Receipt of vaccinations during pregnancy. Countries are ranked according to those reporting "yes" in 2019.

3

Ever chosen to not vaccinate during pregnancy. Countries are ranked according to those reporting "no" in 2019.

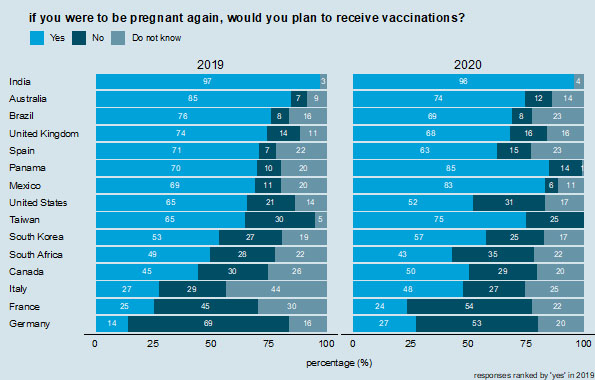

4

Future vaccination intent during pregnancy. Countries are ranked according to those reporting "yes" in 2019.

Interestingly, larger proportions of respondents in 2020 report that they would not vaccinate in a future pregnancy than state they have ever chosen to not get a vaccine during pregnancy. In Germany and France in 2020, for example, 53 and 54% of respondents, respectively, state they would not plan to receive vaccinations if they were pregnant again (Figure 4), compared to 25 and 24%, respectively, who said they had chosen not to get a vaccination during pregnancy (Figure 3). Similar (but smaller) differences are observed in Canada, Italy, South Africa, Taiwan, and the USA (Figures 3 and 4). The largest proportions of respondents in 2020 who state that they would not plan to receive vaccinations in a future pregnancy are in France (54%), Germany (53%), and South Africa (35%). Germany (69%) and France (45%) also had the two highest proportions in 2019.

The country-specific regressions revealed that having a general awareness about the vaccines provided during pregnancy is positively associated with maternal vaccination uptake in nine out of the 14 countries analyzed (2019 data). The effect sizes are especially large in Brazil, South Africa, and Spain (2019 data). Knowledge about maternal vaccines is known to strongly influence vaccination acceptance in a range of settings, particularly in low- and middle-income countries.25,26,27,28

VACCINE ACCEPTANCE

Our quantitative analysis identified that strong predictors of vaccination in pregnancy included awareness of vaccines in pregnancy, perceptions that vaccines during pregnancy are important, and a healthcare provider recommendation. Country-level variations were observed. Australia, the UK, Brazil, and the USA have the highest level of maternal vaccination awareness, while South Africa, France, Italy, and Germany had the lowest awareness. Participants from India, Brazil, Panama, and Mexico had the highest proportion of women who agreed that maternal vaccines are important, while Germany, France, and South Korea had the lowest proportion. We will explore the key themes.

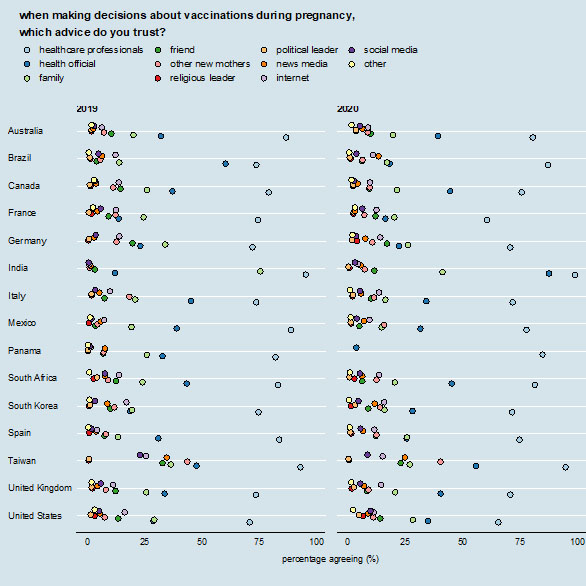

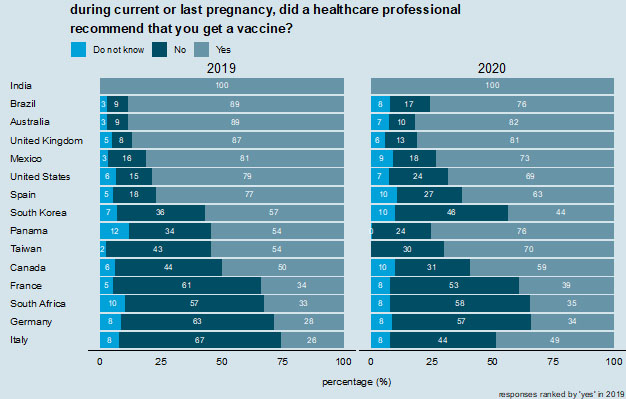

Sources of information

Most women in the global 2020 survey reported that healthcare providers and health officials are the most trusted sources of information for maternal vaccination decisions (Figure 5). Responses in 2020 ranged from 34% in Germany to 100% in India (Figure 6). In 2019, Italy had the lowest proportion of respondents stating they had received a healthcare professional recommendation for a vaccine (26%), but this has increased to almost half of respondents (49%) in 2020 (Figure 6).

“We trust only doctors during that time. During pregnancy, we cannot risk listening to others.” (FG314, Hyderabad)

“We have faith in Doctor. Doctor is educated and so we trust him. If he is giving injection, we will trust that he is right.” (IDI124, Delhi)

“You go to a doctor and know that that person has studied and has a certain amount of medical knowledge that’s why it’s hard for me not to trust a doctor and not to listen to his or her recommendations.” (FG337, Germany)

“He said to me that he wasn’t pro or against it but because he was a doctor he must do it. He said ‘it’s up to you, for me it’s not necessarily useful’. So I said "ok, I trust you." (IDI34, France)

Pregnant women in several countries appreciate specialists such as midwives (e.g., Australia, France, Germany, Spain, the UK) who make them feel empowered to choose for themselves. The interviews and focus groups identified that gynecologists are the key source of information and recommendations around vaccines during pregnancy in Germany and Italy.

Furthermore, patient relationships with primary care providers are critical to determine whether views on vaccinations are cemented as positive, or skeptical (e.g., France, India, Mexico, Panama, Spain, the UK).29 Pregnant women appreciate continuity with healthcare professionals throughout their pregnancy, which aids building rapport and trust.30 Those who seek generalized information are more likely to turn to gynecologists, while for questions or doubts about safety or efficacy they are more likely to turn to their midwives for guidance (e.g., Australia, Germany).

"I trust my doctor. Everything that he prescribes, I will take. He has been my doctor for the past 7 years. Everything that he says I listen to because I have it in my head that he studied to become a doctor and he knows more than I do so if he tells me that something is good for me, I will take it." (FGD, Brazil)

“I talked about it to the gynecologist, he told me to get vaccinated but you know, he is not . . . the consultation lasts 5 minutes, I asked him the question if he thought it was ok to get vaccinated now, he said ‘yes, yes it would be very good, have a good day, bye.’” (IDI30, France)

“no one really tells us what the advantages are of getting vaccination while being pregnant. I mean my gynecologist just told me to get it and who knows maybe she is lacking information herself but then don’t recommend something you don’t have enough information about.” (FG338, Germany)

5

Sources that are trusted for information on vaccinations during pregnancy. Each colored dot shows the percentage of respondents who report that source as being one that they trust for information about vaccines during pregnancy. Percentages do not sum to 100% as respondents can select multiple sources.

6

Did a healthcare professional recommend a vaccine during pregnancy. Countries are ranked according to those reporting "yes" in 2019.

Some reported a lack of confidence in the financial motives of some healthcare providers (e.g., Germany, France, South Korea, and Taiwan), and others expressed a concern about whether healthcare providers are able to give completely independent medical advice. A high proportion of participants in some countries (e.g., Germany, South Korea, Taiwan, the UK, the USA) believe that medical professionals are unduly influenced by pharmaceutical companies and/or financial incentives.

“doctors sell stuff too and they’re told to sell stuff. We don’t know if it is actually their own opinion” (FG303, France)

“government doesn’t get profits from selling vaccines, but doctors do.” (IDI198, S Korea)

While healthcare professionals are generally the most influential source of information in all countries, pregnant women generally also receive and seek information from a wide range of other sources (family, friends, news, internet, social media, apps) (Figure 5).

In a majority of the countries surveyed, mothers reported conferring with family and friends with children about vaccinating in pregnancy. Women interviewed in all countries were likely to cite their mothers, sisters, and other close family members as sources of trust when making decisions about vaccinations, as their mothers and sisters, based on their experience and having made similar decisions about vaccinations during pregnancy and for their children. India is unique in the countries studied, in that men within the family appear to take a much larger role in the pregnancy compared to other countries. Awareness of family involvement (such as the role of men and mothers-in-law in influencing maternal vaccine decision-making in India) should be further considered when designing communication and engagement strategies.

“Gynecologist is the most reliable one so as to answer all my questions. Then comes my mother, or my mother-in-law, but initially it is doctor.” (FG, Delhi)

“I speak to my mother since she’s already gone through this. My mother talks to me about everything. She says to me, 'Look, it’s not like that. It’s like this . . . you’re going to experience this.'” (FG1, San Miguelito)

“Doctors have the most credibility. The next is experience from my friends. I also trust family members, but I have to see how old that person is. I don’t trust someone whose experience is from more than five years ago.” (IDI165, Taipei)

“Opinions from my in-laws are quite low down there. Then it’s opinions from my husband. Then opinions from info online. And then it is opinions from the doctor, on the top.” (IDI178, New Taipei)

Research shows that mothers in South Korea have picked up concerns relating to vaccines from the local and regional press, but often find it difficult to get detailed information from doctors when they raise concerns. This is partly due to the time pressure on doctor’s appointments, but there are also concerns that doctors are financially motivated to recommend vaccines that may not be beneficial. Often this leads to mothers seeking a wide array of sources to get the necessary information needed to make a final decision on whether or not to take a vaccine.

An important finding is that while healthcare providers (80%) and family members (27%) were listed as the most trusted sources for maternal vaccination decisions globally, the proportion of women who trusted the internet for vaccination-related information was lower (11%). Taiwan (26%) and the USA (16%) had the highest proportion of women who reported trusting the internet for vaccination-related information. Taiwan also had the highest proportion of women who trusted social media (23%) for information to make decisions on maternal vaccination.

Our media monitoring analysis identified that most of the content on social media around maternal vaccines was promotional (e.g., posts communicating public health benefits or safety of vaccination) (52%), followed by ambiguous (e.g., content containing indecision, uncertainty on the risks or benefits of vaccination) (21%), discouraging (e.g., containing negative attitudes or arguments against maternal vaccines) (18%), and neutral (e.g., statements, devoid of emotion) (9%). The USA had the highest amount of discouraging (22%) and ambiguous (25%) posts. The UK had the highest proportion of promotional posts (80%). There were clear differences in content by platform. The most ambiguous content was found on mother’s forums whilst the most discouraging content, as well as the most promotional content was found on Twitter. Forums provide spaces for longer discussions and were important sources of support for decisions on maternal vaccines whilst Twitter was more dominated by official public health institutions and groups deliberately spreading discouraging content.

In the interviews and focus groups we identified that those with questions went to the Internet seeking starting points for information – with some caution and awareness of the "anti-vax" community and the arguments it presents against vaccination.31,32 Vaccine critical arguments are widely known and gaining ground (e.g., Italy). As anti-vaccination arguments become increasingly mainstream on the Internet and social media, it is important to ensure that these are not the first sources of information on vaccination that women encounter. It is worth monitoring the nature of vaccine sentiments – particularly online – as anti-vaccine views become increasingly widespread and, potentially, more influential among the mainstream population.

“I was Googling, but then I found that if you Google something for long enough, you will find that you are definitely having a miscarriage or dying, so I try to stay away from Google.” (FGD, Australia)

“There is the fake news problem, many things online are not true . . . Unfortunately, the same way the internet can help with information, it might bring lies and problems.” (RJ, Brazil)

“if I’ve got to wait too long for my next appointment, then I look it up on Google.” (FG4, Panama City)

“I obtain the opinions of online communities and make a final decision myself.” (IDI184, S Korea)

Reasons for and against vaccination during pregnancy

Most participants in all countries raised concerns about the risks associated with vaccination, and possible side effects for the baby.33 The supposed connection between vaccines and autism was front-of-mind in Italy in a way that it was not in other countries. Even those who were pro-vaccine and rejected the claim were still very aware of the argument promoted by those who oppose vaccines.

“They tell us that small medicines are forbidden, even cough syrup is forbidden, so I don’t really understand why this would be authorized.” (IDI22, France)

“I’m creating a baby, I would rather create him peacefully and when he’s going to be out, I will do all the vaccines peacefully but not during the creation.” (IDI30, France)

“you are always afraid that something might have a negative and dangerous effect on the fetus.” (IDI88, Italy)

“I’m afraid of negative reactions in my body. Perhaps my reaction could be different and negative, maybe it will harm the baby or me, that is what generates my uncertainty.” (IDI4, Mexico City)

In countries with compulsory vaccines (e.g., Australia, Brazil, France, the USA), any non-compulsory vaccines were more likely to be refused as they were perceived as being less important; communications around how risks vary across different groups could help to tackle this "two-tier" problem. It should be noted that some mothers (e.g., Australia) resent the presentation of vaccines, such as against whooping cough, as a requirement rather than a choice, and appreciate specialists such as midwives who make them feel empowered to choose for themselves.

"with this midwifery group practice it’s actually a little bit, you know, it’s not as black and white as it is in the other system . . . These midwives are a bit more, you know, 'Well you could do this, you could do that' . . . it’s good to know that they are the professionals who are prepared to, you know, trying to give you two options . . . saying 'You have the choice, you know to go on and do it yourself,' go on researching yourself." (FGD, Australia)

Cost was seen as a barrier to vaccination in several countries (e.g., Australia, India, South Africa, South Korea), with Taiwan being characterized as having a more commercial angle around vaccinations compared to other countries in this study. Research suggests that the Taiwanese government is seen as a trustworthy authority on vaccine information, both in its public communications and in provision of free essential healthcare. South Korean mothers express high levels of trust in state healthcare, and a vaccine being covered by universal health insurance is seen as almost a guarantee of its necessity. This means that where a vaccine is only covered by additional insurance/at further cost, mothers in South Korea were left wanting accessible, detailed information from the government on the pros and cons of treatments/vaccines so they could determine whether the benefits justified the expenditure.

Pregnant women are more risk averse in general, and vaccination during pregnancy is a source of anxiety. Women feel little motivation to introduce what they perceive as a possible risk during this sensitive time of life.

“It’s enormous. I don’t even drink coke during my pregnancy so a vaccine . . .” (IDI36, France)

"I think that in a pregnant woman the risk of [vaccine] injury is higher." (IDI 243 RJ, Brazil)

“I think it’s the fact that you are responsible for another human life. It makes everything more complicated.” (FG338, Germany)

Overall, pregnant women in Mexico seemed to trust vaccinations, but did not trust the public healthcare system. The level of care associated with public health is deemed unsatisfactory for several reasons (such as less detailed advice), which has contributed to a lack of willingness to engage with the public system as a whole. With a lack of trust in and willingness to engage with the public health system, there is a risk that trust in suggested treatments, vaccines included, will decrease.

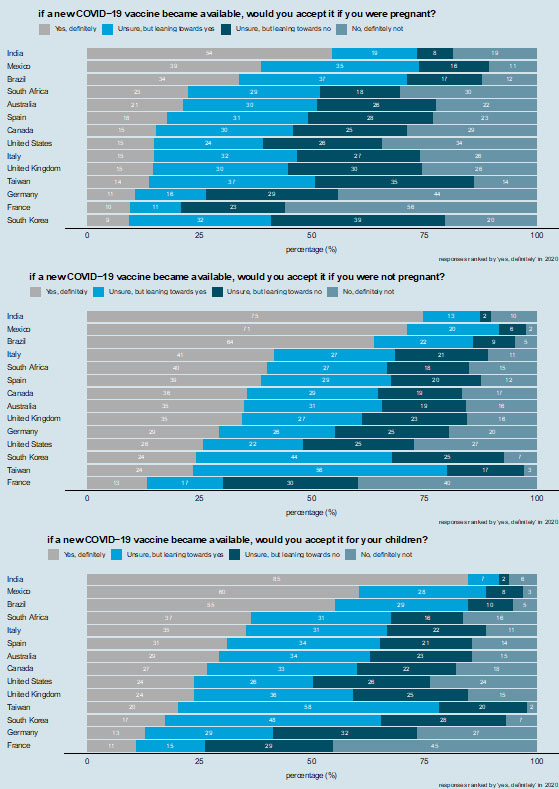

Covid vaccination

There is substantial variability in intent to accept a COVID-19 vaccine (Figure 7). Only India had a majority of respondents (54%) who state they would “definitely” accept a COVID-19 vaccine during pregnancy (Figure 7, top row). India is followed by Mexico (39%) and Brazil (34%), but then there is a large drop off to other countries. The same dichotomy of countries is observed in intent to accept a COVID-19 vaccine outside of pregnancy and for their children, with majorities of respondents stating they would "definitely" accept the vaccine in India (75% would accept the vaccine outside of pregnancy and 85% would accept the vaccine for their children), Mexico (71 and 60%), and Brazil (64 and 55%) (Figure 7 middle and bottom row). Italy (41 and 35%) and South Africa (40 and 37%) are the countries with the next highest proportion of respondents who would accept a COVID-19 vaccine for themselves, if they were not pregnant, or for their children (respectively) (Figure 7 middle and bottom row).

Most respondents in all countries except the USA (48%) and France (30%) would either "definitely" or be "leaning towards" accepting a COVID-19 vaccine for themselves outside of pregnancy (Figure 7 middle row). Intent to accept a COVID-19 vaccine outside of pregnancy is particularly low in France, with only 13% of women surveyed stating they would "definitely" accept a new COVID-19 vaccine. A similarly low proportion in France (11%) would "definitely" accept a COVID-19 vaccine for their children (Figure 7 bottom row).

7

Intent to accept a COVID-19 vaccine. Respondents are asked whether they would accept a COVID-19 vaccine for themselves while they were pregnant (top row), if they were not pregnant (middle row), and whether they would accept the vaccine for their children (bottom row). Countries are ranked according to those reporting "yes, definitely" in 2020.

Acceptance of participating in future maternal vaccine trials

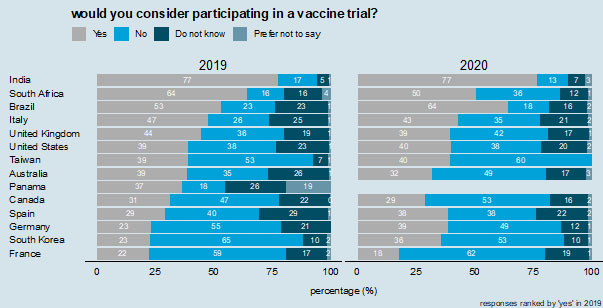

For the most part, women who were part of this research in all countries reported an unwillingness to take part in vaccine trials during pregnancy. In this they cite the concerns that trials will threaten the success of the pregnancy or the overall health of the fetus. The majority of respondents in only three countries in 2020 say that they would consider participating in a vaccine trial (India, 77%; Brazil, 64%; and South Africa, 50%) (Figure 8). These same three countries also had a majority in 2019. Willingness to consider participating in a vaccine trial is notably low in France, where only 18% of respondents in 2020 would consider participating.

Women who would be willing to partake in vaccine trials stated that they would need to be convinced that there will be no impact on the pregnancy or on baby’s health; given this is inherently impossible, this reveals a potential lack of understanding rather than a genuinely positive view of trials.

“I think it’s pretty scary . . . because it’s not just putting yourself at risk, it’s also putting an unborn baby at risk.” (IDI – 287, Vancouver)

“It’s an experiment, we don’t know if it’ll be successful or it. There is a danger to two lives – the mother and child. If everything is okay, then it’s fine but we can’t say if it’ll be successful right?” (IDI139, Hyderabad)

Regarding vaccine clinical trials participants in almost all countries displayed a willingness to participate in trials to test new vaccines’ efficacy but were unwilling to consider trials if the vaccine was not yet confirmed as being fully safe.

"Well definitely, if the safety has been approved . . . but I still don’t think would do it. I mean, I guess I feel more positively about it, but yes, I guess I’m conscious about having an evidence-base, [but] I don’t want to be part of something that creates that evidence base." (IDI 155, Australia)

Willingness to participate is caveated by the need for recommendations from the doctor to endorse a particular trial (e.g., India) – a finding that is unsurprising since significant importance is placed on doctors’ recommendations. Any invitation to maternal vaccine trials should be done through healthcare professionals.

“If the doctor talk to me and tells me about it, why not? Because I'm also aware that they need people who test to make progress, and because testing on animals is not good either. So, we need people to test. But I don't want to put my baby's life or my life in danger.” (IDI – 291, Montreal)

“[Would you take part in a trial?] I’m not sure. If a doctor told me to, then I would do it. Any person will follow the doctor, because the doctor has more knowledge than us.” (IDI140, Hyderabad)

8

Willingness to consider participating in a vaccine trial. Responses are ranked by "yes" (would consider participating) in 2019.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- Improve public awareness of maternal vaccines – including the reasoning behind giving them. Efforts should be taken to increase public awareness and understanding of the need to vaccinate during pregnancy.

- Improve communication and dialog between pregnant women and their doctors around vaccination. It is crucial that any outreach to mothers directly is coordinated between various key trusted healthcare professionals for the specific country.

- Concentration should also be applied to improving the quality and increasing the volume of vaccine-related information given to women by their doctors. Even though they are likely to take their doctor’s advice, without understanding of the risks associated with not vaccinating, there is a potential for pregnant women to reject vaccines that they do not deem necessary. An absence of information from official sources adds to an atmosphere of uncertainty around certain vaccines, which, if left unchecked, could increase vaccine-hesitancy.

- The way that flu has been framed has led some pregnant women to view influenza as an illness that only affects the elderly. Care must be taken to shape messaging in vaccine information campaigns.

- Further research is needed to explore further why in certain countries some healthcare providers are recommending pregnant women not to vaccinate.

- Awareness of family involvement should be further considered when thinking about disseminating information on available vaccinations during pregnancy for expectant mothers.

- Monitor the nature of the vaccine debate – particularly online – as vaccine-critical views become increasingly widespread and, potentially, more accepted by the mainstream.

- Tailor additional efforts to encourage willingness to participate in maternal vaccine trials, with appropriate engagement depending on the setting and trial specifics.

- To improve promotional content campaigns, focus on the protectiveness and safety of a maternal vaccine, rather than the threat of disease and clearly communicate the vaccine approval processes.

- Protect public trust in the safety and efficacy of vaccines, with country- as well as region-specific targeted evidence-based interventions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Vaccine Confidence Project (VCP) would like to acknowledge our long-term partnership with WIN/Gallup International Association (WIN/GIA). HJL and PP are affiliated to the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Protection Research Unit in Vaccines and Immunization at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine in partnership with UKHSA. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the National Health Service, the NIHR, the Department of Health, or UKHSA.

The authors would like to thank Emilie Karafillakis, Mark Francis, Alex de Figueiredo, Rizu Rizu, Sarah Dada, Kristen de Graaf, Valerie Heywood, Eliz Kilich, Tatjana Marks, Sam Martin, Ed Pertwee, and Fiona Sun for their contributions to this project.

FUNDING

This work was supported by GlaxoSmithKline(GSK). The funder reviewed the study protocol but had no role in data collection, analysis, interpretation, or writing of this book chapter.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

In addition to the acknowledged funding from GSK for this study, the Vaccine Confidence Project has received funding grants from Merck and JJ for studies on vaccine acceptance

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

REFERENCES

WHO. Vaccines against influenza WHO position paper – November 2012. [Internet]. Weekly epidemiological record. 2012. Available from: http://www.who.int/wer/2012/wer8747.pdf?ua=1. | |

Abramson JS, Mason E. Strengthening Maternal Immunisation to Improve the Health of Mothers and Infants. The Lancet 2016;388(10059):2562–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30882-0. | |

WHO. Pertussis vaccines: WHO position paper – August 2015. [Internet]. Weekly epidemiological record. 2015. Available from: http://www.who.int/wer/2015/wer9035.pdf?ua=1. | |

WHO Tetanus vaccines: WHO position paper – February 2017. [Internet]. Weekly epidemiological record. 2017. Available from: http://www.who.int/immunization/policy/position_papers/tetanus/en/. | |

Kyu HH, Mumford JE, Sanaway JD, et al. Mortality from Tetanus between 1990 and 2015: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. BMC Public Health 2017;17(179). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4111-4. | |

Vojtek I, Dieussaert I, Doherty TM, et al. Maternal Immunization: Where Are We Now and How to Move Forward? Annals of Medicine 2018;50(3):193–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890.2017.1421320. | |

Razzaghi H, Kahn KE, Black CL, et al. Influenza and Tdap Vaccination Coverage Among Pregnant Women – United States, April 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69(39):1391–7. | |

UKHSA. Seasonal influenza vaccine uptake in GP patients: winter season 2020 to 2021. [Internet]. 2022. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/996033/Annual-Report_SeasonalFlu-Vaccine_GPs_2020_to_2021.pdf. | |

UKHSA. Pertussis vaccination programme for pregnant women update: vaccine coverage in England, October to December 2021. Health Protection Report Volume 16 Number 4. 22 March 2022. 2022. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1061785/hpr0422_prtsss-vc.pdf. | |

Laenen J, Roelants M, Devlieger R, et al. Influenza and pertussis vaccination coverage in pregnant women. Vaccine 2015;33:2125–31. | |

Castro-Sánchez E, Vila-Candel R, Soriano-Vidal FJ, et al. Influence of health literacy on acceptance of influenza and pertussis vaccinations: a cross-sectional study among Spanish pregnant women. BMJ Open 2018;8:e022132. | |

Mohammed H, Clarke M, Koehler A, et al. Factors associated with uptake of influenza and pertussis vaccines among pregnant women in South Australia. PLOS ONE 2018;13:e0197867. | |

Wilson RJ, Paterson P, Jarrett C, et al. Understanding factors influencing vaccination acceptance during pregnancy globally: A literature review. Vaccine 2015;33:6420–9. | |

Ball S, Donahue S, Izrael D, et al. Influenza Vaccination Coverage Among Pregnant Women – United States, 2012–13 Influenza Season. MMWR. 2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2013;62(38):787–92. | |

Goldfarb I, Panda B, Wylie B, et al. Uptake of Influenza Vaccine in Pregnant Women during the 2009 H1N1 Influenza Pandemic. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2011;204(6 Suppl 1):S112–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2011.01.007. | |

Liu N, Sprague AE, Yasseen AS 3rd, et al. Vaccination Patterns in Pregnant Women during the 2009 H1N1 Influenza Pandemic: A Population-Based Study in Ontario, Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health 2012;103(5):e353–8. | |

Bödeker B, Walter D, Reiter S, Wichmann O. Cross-sectional Study on Factors Associated with Influenza Vaccine Uptake and Pertussis Vaccination Status among Pregnant Women in Germany. Vaccine 2014;32(33):4131–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.06.007. | |

Boyd CA, Gazmararian JA, Thompson WW. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behaviors of Low-Income Women Considered High Priority for Receiving the Novel Influenza A (H1N1) Vaccine. Maternal and Child Health Journal 2013;17(5):852–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-012-1063-2. | |

Cheng PJ, Huang SY, Shaw SW, et al. Factors Influencing Women’s Decisions Regarding Pertussis Vaccine: A Decision-Making Study in the Postpartum Pertussis Immunization Program of a Teaching Hospital in Taiwan. Vaccine 2010;28(34):5641–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.05.078. | |

Kang HS, De Gagne JC, Kim JH. Attitudes, Intentions, and Barriers Toward Influenza Vaccination Among Pregnant Korean Women. Health Care for Women International 2015;36(9):1026–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2014.942903. | |

MacDougall DM, Halperin SA. Improving Rates of Maternal Immunization: Challenges and Opportunities. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics 2015;12(4):857–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2015.1101524. | |

WHO. WHO SAGE values framework for the allocation and prioritization of COVID-19 vaccination. [Internet]. 14 September 2020. 2020. Available from: file:///C:/Users/eidepbro/Downloads/WHO-2019-nCoV-SAGE_Framework-Allocation_and_prioritization-2020.1-eng%20(1).pdf. | |

Maruta L. TRAC: Engagements. [Internet]. Intercom.help. 2020. Available from: https://intercom.help/pulsar/en/articles/670401-trac-engagements. | |

Li WF, Huang SY, Peng HH, et al. Prenatal Pertussis Immunization Program (PPIP) Collaboration Group. Factors Affecting Pregnant Women’s Decisions Regarding Prenatal Pertussis Vaccination: A Decision-Making Study in the Nationwide Prenatal Pertussis Immunization Program in Taiwan. Taiwanese Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 2020;59(2):200–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tjog.2020.01.006. | |

Eppes C, Wu A, You W, et al. Barriers to Influenza Vaccination among Pregnant Women. Vaccine 2013;31(27):2874–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.04.031. | |

Taksdal SE, Mak DB, Joyce S, et al. Predictors of Uptake of Influenza Vaccination–a Survey of Pregnant Women in Western Australia. Australian Family Physician 2013;42(8):582–6. | |

Barrett T, McEntee E, Drew R, et al. Influenza Vaccination in Pregnancy: Vaccine Uptake, Maternal and Healthcare Providers’ Knowledge and Attitudes. A Quantitative Study. BJGP Open 2018;2(3). https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgpopen18X101599. | |

Larson Williams A, Mitrovich R, Mwananyanda L, Gill C. Maternal Vaccine Knowledge in Low- and Middle-Income Countries – and Why It Matters. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics 2018;15(2):283–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2018.1526589. | |

Karafillakis E, Paterson P, Larson HJ. ‘My primary purpose is to protect the unborn child’: Understanding pregnant women’s perceptions of maternal vaccination and vaccine trials in Europe. Vaccine 2021;39(39):5673–9. | |

Karafillakis E, Francis MR, Paterson P, et al. Trust, emotions and risks: Pregnant women’s perceptions, confidence and decision-making practices around maternal vaccination in France. Vaccine 2021;39(30):4117–25. ISSN 0264-410X. | |

Simas C, Larson HJ, Paterson P. ‘Those who do not vaccinate don’t love themselves, or anyone else’: a qualitative study of views and attitudes of urban pregnant women towards maternal immunisation in Panama. BMJ Open 2021;11(8):e044903–. ISSN 2044-6055. | |

Simas C, Paterson P, Lees S, et al. ‘From my phone, I could rule the world’: Critical engagement with maternal vaccine information, vaccine confidence builders and post-Zika outbreak rumours in Brazil. Vaccine 2021;39:4700–4. | |

Simas C, Larson HJ, Paterson P. "Saint Google, now we have information!": a qualitative study on narratives of trust and attitudes towards maternal vaccination in Mexico City and Toluca. BMC Public Health 2021;21:1170. ISSN 1471-2458. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards program CLICK HERE)