This chapter should be cited as follows:

Velez IC, Kachikis A, Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.417973

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Obstetrics Module

Volume 17

Maternal immunization

Volume Editors:

Professor Asma Khalil, The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, London, UK; Fetal Medicine Unit, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, St George’s University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK

Professor Flor M Munoz, Baylor College of Medicine, TX, USA

Professor Ajoke Sobanjo-ter Meulen, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

Chapter

The Role of Maternal Health Providers to Protect Pregnant Women Through Vaccination

First published: May 2023

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

Over the last decades, maternal immunization, the vaccination of pregnant individuals to provide active immune protection to the pregnant person and passive immune protection to her fetus and infant, has been increasingly utilized as an important disease prevention strategy. Influenza, tetanus, pertussis, and COVID-19 vaccines are currently recommended routinely during pregnancy by the World Health Organization (WHO) and other national health authorities.1,2 In addition, several vaccines against pathogens such as respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and Group B Streptococcus (GBS) for use in pregnancy are currently in development or in clinical trials.3

Vaccines in pregnancy have been demonstrated to significantly decrease risk of infection and adverse pregnancy outcomes due to infection in pregnant individuals and also their infants via active transfer of maternal immunoglobulin (IgG) across the placenta during pregnancy.4,5,6,7 However, despite growing evidence regarding the benefits of immunizations during pregnancy, rates of vaccination coverage among the pregnant population are lagging. For example, in 2021, 64.5 and 53.3% of pregnant individuals received a pertussis vaccination in the United Kingdom (UK) and in the United States (US), respectively.8,9 Furthermore, studies have demonstrated that national vaccination rates in pregnancy can differ widely based on racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups.10,11,12,13

Studies on vaccine uptake and vaccine hesitancy in the pregnant population have identified several factors that influence the decision of a pregnant person to receive a vaccine and barriers that prevent them from accepting a vaccine.14 However, in determining the decision of a pregnant person to be vaccinated, one of the most significant factors is whether the healthcare provider recommends the vaccine.15 The objective of this chapter is to explore the role that maternal health providers play in vaccine acceptance among pregnant individuals, the relationship between pregnant people and maternal health providers, and characteristics of maternal health providers themselves that may lead to increased recommendations and thereby broader coverage of maternal immunizations.

3CS FRAMEWORK

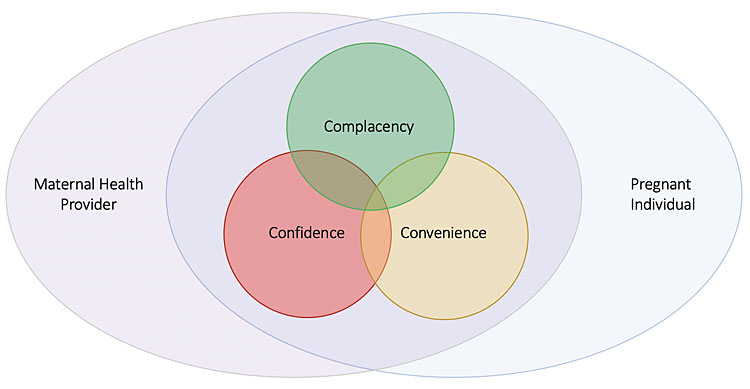

Vaccine hesitancy, as defined by the WHO, refers to the delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite availability of vaccine services. In 2011, the WHO Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE) convened the SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy due to the growing acknowledgment of vaccine hesitancy as detrimental to global immunization programs, one of the most effective means to improving health outcomes worldwide.16 To more specifically define vaccine hesitancy and categorize its complex determinants, the Working Group introduced the complacency, convenience, and confidence (“3Cs”) framework of vaccine hesitancy. “Confidence” is the trust in the vaccine effectiveness, safety, systems, and policy makers. “Complacency” is present when the perceived risks of vaccine-preventable diseases are low along with low motivation to vaccinate. Finally, “convenience” is related to the various services that affect vaccine uptake, including availability of vaccines, cost, ability to understand recommendations.16 In this chapter, the “3C” model will be used as a framework to understand factors that are specific to health providers and their recommendation of these vaccines as well as characteristics of the provider–patient relationship. Ultimately, maternal health providers and the healthcare system are tasked with increasing confidence and convenience related to maternal immunization, while decreasing complacency. For this to occur, factors that both positively and negatively impact a provider’s ability to recommend maternal vaccination and ultimately influence the “3Cs” of vaccine hesitancy must be identified.

1

3Cs model in the context of the maternal health provider and the pregnant individual. Adapted from the WHO’s SAGE Working Group “Confidence, Complacency, Convenience Model of Vaccine Hesitancy”.16

RECOMMENDATION AND OFFER

Study after study have shown that one of the most important factors in increasing acceptance and uptake of vaccination among pregnant individuals is the recommendation to receive a vaccine by a health care provider and, when possible, an offer to administer the vaccine at that time. Conversely, studies have also shown the absence of a healthcare provider recommendation and offer is a main barrier to vaccination reported by unvaccinated pregnant individuals. The importance of the provider recommendation and offer has been consistently demonstrated across high-, middle-, and low-income countries, across different patient populations, race, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups, as well as vaccine types.3,14,17 For example, a multi-center survey-based study conducted in Italy in 2018, which included 743 pregnant people, showed the recommendation to vaccinate against influenza and pertussis by a maternal care provider to be the main facilitator among vaccinated respondents (62%), while the main barrier to vaccination was a lack of vaccine recommendation by any healthcare provider (81%).18 In a French study, which included 2,045 women, greater influenza vaccination uptake was reported in respondents who had received a recommendation during pregnancy by a healthcare worker (47%) compared to those who self-reported no recommendation (2.7%).19 Additionally, a cross-sectional study from Singapore looking at coverage and determinants of influenza vaccination in pregnancy found that the most frequently reported reason for not receiving the influenza vaccine was lack of healthcare provider recommendation and those who did receive a recommendation were seven times more likely to get vaccinated.20 Reaffirming the role of the healthcare provider as the recommender, a mixed-methods study from Malawi in 2015 found that community healthcare workers were identified by pregnant individuals as their main source of information on whether to receive vaccines.21

Highlighting the importance of a compelling recommendation by a healthcare provider in addition to an offer or referral to vaccinate, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United States conducted a survey-based study in 2021 assessing influenza and Tdap vaccination coverage in pregnant people. Of the 2,300 respondents who completed the survey, influenza vaccination was highest in those who were recommended and offered the vaccine or provided a referral (68.1%) compared to pregnant women who only received a recommendation but no referral (29.1%) or no recommendation at all (17.4%). For the Tdap vaccine, it was reported that coverage was higher in women who received an offer or referral (69.9%) compared to those with only a recommendation but no referral (24.7%).8 Similarly, a multi-site study conducted in 2016 in Nicaragua found that among 1,303 pregnant people influenza vaccination rates were highest for those who received a recommendation and offer (95%) compared to those who received only a recommendation (81%) or neither a recommendation nor offer (5%).22 These studies emphasize the critical role providers and health systems have in providing maternal immunization recommendations as well as enabling pregnant individuals to be vaccinated through immediate administration of the vaccine or referral.

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE MATERNAL HEALTH PROVIDER–PATIENT RELATIONSHIP IN IMPROVING MATERNAL VACCINATION ACCEPTANCE AND UPTAKE

Patient awareness of vaccine recommendations

Numerous studies have also shown unvaccinated patients commonly are unaware of maternal vaccination recommendations or have insufficient information. Lacking or insufficient knowledge of vaccine recommendations amongst pregnant individuals can be considered a proxy for absence of a compelling health provider recommendation and further illustrates the important role of the maternal health provider in encouraging maternal immunization. For example, a survey-based study conducted in Saudi Arabia investigating uptake of influenza vaccination in pregnancy found key barriers include poor recognition that the vaccine is safe in pregnancy (13.1% of survey respondents) or lack of awareness that the vaccine is recommended in pregnancy (19.1% of survey respondents) as major barriers to influenza vaccination amongst pregnant women.23 Similarly, an Italian study found that lack of awareness of recommendations for vaccines in pregnancy to be a significant barrier for study participants.24 In a Canadian study, 40% of women who did not receive the influenza vaccine, which included women that indicated initially intending to be vaccinated, self-reported that they did not have sufficient information to make the decision.25 Studies exploring pertussis vaccination in pregnancy have found similar trends, such as in Taiwan and Ireland where cross-sectional studies found that 55 and 59% of unvaccinated women, respectively, reported the reason for not receiving the vaccine was insufficient information.26,27

Effective communication

Communication between healthcare providers and patients is essential and it is imperative to avoid ineffective transfer of information or intended messaging between parties. A variety of research and resources have been devoted to helping providers more effectively communicate to pregnant individuals the safety and importance of maternal immunization both for the individual and the infant.28 An example of ineffective transfer of information is demonstrated in a study conducted in Nicaragua in 2016. In this study, it was reported that 89% of the 619 health providers enrolled in the study recalled recommending the influenza vaccine to all pregnant patients. Of these pregnant women, only 44% recalled receiving the recommendation. Similarly, in the United States, a study linking health provider and patient survey responses with electronic medical records from 2013–2015 showed that 100% of the 76 health providers included in the study documented making a recommendation for the influenza vaccine to all pregnant individuals, however, only 85% of the participating patients reported receiving the recommendation.29 While the WHO SAGE Working Group does not define communication as a determinant of vaccine hesitancy like the “3Cs”, it does recognize communication as a critical tool in ensuring maternal immunization acceptance.16 Other factors that may improve effective communication include face-to-face discussions as well as ensuring sufficient time is allotted for counseling. In an interview-based study in the UK, most participants reported that health professionals did not spend sufficient time discussing benefits and risks or were not able to answer all questions.30

Trust

Providing clear recommendations and utilizing strategies that encourage effective communication builds trust between maternal health providers and pregnant patients. “Confidence” is one of the “3Cs” of the WHO SAGE model on vaccine hesitancy, where trust in vaccine recommendations, the health system, and health care providers are essential determinants of maternal immunization acceptance.16 In an in-depth, interview-based study looking at how trust influences maternal vaccine acceptance amongst pregnant women in Kenya, a central finding was the integral nature of patients’ trust in health providers. As part of trust-building, this study also highlighted that providing pregnant women sufficient information to make informed decisions could contribute to trust between the health provider and patient.31 Similarly, a mixed-methods study conducted in El Salvador, one of the countries with the highest reported coverage rates for influenza immunization in pregnancy globally, explored the implementation of maternal influenza vaccination and identified a high degree of trust between the community and health providers as a key factor of vaccine acceptance. Study participants initially reported mistrust of the influenza vaccine resulting from rumors on social media. Stakeholders interviewed agreed that increase in community acceptance of the influenza vaccine was due to improvements in knowledge and awareness of the vaccine amongst health workers.32 This highlights the critical responsibility providers have in understanding maternal influenza recommendations so that they can educate patients thoroughly and impart confidence in their pregnant individuals.

In addition to fostering general confidence with all pregnant patients, special care and emphasis must be placed by maternal health providers to build trust amongst minority groups that traditionally have experienced higher rates of health inequity, including racial and ethnic minorities. In a study conducted in the United States, black and Hispanic participants were less likely to trust vaccine information from healthcare providers and public health providers.33 Similarly, a cross-sectional study in the UK found that among an ethnically diverse group of pregnant individuals in London, pertussis vaccine uptake during pregnancy could be significantly increased if a recommendation for the vaccine were made by a familiar healthcare professional.34 It is important to recognize that distrust, rooted in a history of health inequity and abuse of people of color or minorities as well as ongoing structural racism embedded in medicine and more broadly, may need to be addressed in order to build trust between the maternal health provider and the pregnant person.

CHARACTERISTICS OF MATERNAL HEALTH PROVIDERS THAT INFLUENCE RECOMMENDATION OF MATERNAL IMMUNIZATION

Knowledge and biases

A variety of maternal health provider attributes influence a provider’s ability or desire to make a compelling recommendation for advised vaccines in pregnancy. Numerous studies have reported that provider biases as well as knowledge gaps continue to greatly affect a health provider’s ability to thoroughly educate patients on the advised vaccines in pregnancy. For instance, despite demonstrated safety and efficacy of vaccination in pregnancy, perceived safety concerns amongst maternal health providers continues to be a barrier to vaccination. The 2020 literature review by Morales et al. investigating determinants and barriers to maternal influenza vaccination found that the most frequently cited barrier to provider recommendation was concerns about safety and efficacy. This was cited in 75% of included studies across low-, middle-, and high-income countries.17 To illustrate, in a study conducted in Thailand, one third of physicians did not believe the influenza vaccine was safe or effective for pregnant individuals or their fetuses35while in the United States, about one-third of health providers were concerned or very concerned about the safety of the influenza vaccine in the first trimester.29 Other studies have also found similar trends with the Tdap vaccine. For example, in a study conducted in Israel, about one third of healthcare providers reported that the Tdap and influenza vaccines were dangerous or controversial.36

In addition to knowledge gaps and biases related to the safety and efficacy of maternal vaccines, many providers also self-report limited knowledge and confidence as another key barrier to vaccine recommendation. In a multi-center study in the UK looking at the uptake of influenza and pertussis vaccination in pregnancy, researchers found that 25% of healthcare providers reported being “slightly or not confident” in providing advice on the influenza vaccine, while 27% reported being “slightly or not confident” in providing advice on the pertussis vaccine.37 Similarly, in a cross-sectional survey study conducted in France in 2017, 37% of midwives self-reported limited knowledge regarding the influenza vaccine. In this study, high-self evaluated knowledge was found to be related to a higher likelihood of administering the vaccine.38

To improve provider knowledge and confidence regarding maternal vaccine recommendations, government and academic guidelines play a critical role in provider education. In a Korean study conducted in 2019, obstetrician-gynecologists most commonly selected guidelines proposed by public health and academic committees as a factor that would influence future recommendations on maternal immunization.39 Similarly in Thailand, research showed that one of the most commons sources of information used by physicians regarding influenza vaccination in pregnancy was the Ministry of Public Health bulletins and that physicians were more likely to recommend the influenza vaccine to pregnant women if they were aware of this recommendation.35 In Canada, a cross-sectional study on influenza vaccination during pregnancy showed that providers that were aware of the National Advisory Committee on Immunization guidelines were more likely to discuss and recommend the vaccine with patients compared to those who were not aware of the guidelines.40 These studies highlight the critical role international and national health authority and professional organizations’ guidelines play in educating maternal health providers on the latest vaccine recommendations in pregnancy in order to decrease potential biases and increase the likelihood that providers will make a strong recommendation to pregnant individuals to become vaccinated.

Own vaccination status

Another key characteristic of maternal health providers that contributes to maternal vaccine recommendation rates is a provider’s own vaccination status. The literature review by Morales et al., which explored 22 studies across 15 countries found that a healthcare provider’s influenza vaccine status was a main determinant of influenza vaccine recommendation across different provider types.17 Similarly, a French study focusing on midwives also found that midwives that had received the influenza vaccine themselves were more likely to recommend the vaccine to their pregnant patients.38 As health authorities develop educational tools and vaccine guidelines, it is imperative to continue to educate health providers themselves on benefits of vaccines and vaccine guidelines in order to strengthen their recommendation for vaccines in pregnancy.

Clinical experience

Years of experience in clinical care has also been found to be a maternal health provider characteristic that influences the likelihood that the provider will make a recommendation for vaccines to their pregnant patients. Various studies have shown that less experienced healthcare providers are less likely to recommend vaccines in pregnancy. To illustrate, in a study conducted in Thailand, healthcare providers were more likely to recommend the influenza vaccine routinely when the provider had more than 3 years of experience,35 while in France, 50% of midwives with at least 10 years of experience recommended the influenza vaccine compared to only 29% of those who had fewer years of clinical experience.38 These studies highlight the need to target education efforts to early career maternal health providers to increase uptake of recommended vaccines in pregnancy.

Cadre of maternal health provider

A final consideration related to characteristics of maternal health providers is the type of provider responsible for making vaccine-related recommendations to pregnant individuals. While not consistently true, numerous studies have found that obstetrician gynecologists or nurses more frequently give pregnant patients the recommendation to vaccinate as described in the review by Morales et al., which looked at studies across 15 countries.17 While the responsibility of midwives to discuss vaccine guidance with pregnant patients may vary between countries, midwives often play a central role in the care of pregnant patients and their support of vaccine recommendations is critical. Studies in Belgium and Spain have shown that midwives are less aware of vaccine recommendations and may have more safety concerns regarding vaccines.18,41 Thus, it is critical to provide targeted education to all cadres of maternal health providers as illustrated by a study done in Australia where a midwife-delivered immunization program for maternal influenza and pertussis vaccines led to higher vaccination coverage.42

CURRENT RATES OF MATERNAL HEALTH PROVIDER RECOMMENDATIONS

Healthcare provider recommendation rates related to maternal immunization differ across the world. A literature review conducted in 2020 looking at the determinants and barriers to a health providers’ recommendation of the influenza vaccine in pregnancy found that recommendation rates were highest in the Americas (77%) and lowest in Southeast Asia (18%). This review also found that nearly one-third of all 21 studies reviewed reported health provider recommendation rates lower than 50%, including studies conducted in Spain, France, Korea, Georgia, Thailand, China, and India.17 Global differences and generally low rates of recommendation by healthcare providers further highlight the unique opportunity maternal providers have in educating pregnant patients and delivering a strong recommendation and offer to vaccinate.

In addition to global differences, disparities in recommendation and offer rates by health providers also exist in the context of patient race and ethnicity. These differences contribute to existing disparities in maternal vaccination coverage. A literature review published in 2021 looking at a decade of survey data on racial disparities in influenza immunization during pregnancy in the United States showed that black pregnant women have the lowest rate of influenza immunization and report a lower rate of receiving a recommendation and/or offer to receive a vaccine from a health provider.10 Specifically, survey data from the Pregnancy Risks Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) from the CDC showed black pregnant individuals reported 19% lower odds of receiving a provider recommendation compared to non-Hispanic white participants.43 While in 2021 alone the CDC reported offer rates were similar for the influenza vaccine amongst black and white pregnant women in the United States, they did find that black women were less likely to report a healthcare provider offer for the Tdap vaccine.8 In a mixed-methods study in the UK among an ethnically diverse population in 2013 and 2014, among 200 participants, 26% had received the pertussis vaccine during pregnancy, 34.0% of participants were offered the vaccine, but only 24% reported remembering a meaningful discussion with their health provider about the vaccine. Results of this study were also that vaccine uptake differed significantly by ethnicity groups.34 Given the overall low recommendation rates by maternal health providers around the world and existing disparities in vaccine receipt, a renewed focus by providers to strongly recommend maternal vaccines and facilitate administration of these vaccines via an offer or referral could greatly impact maternal vaccine acceptance and uptake.

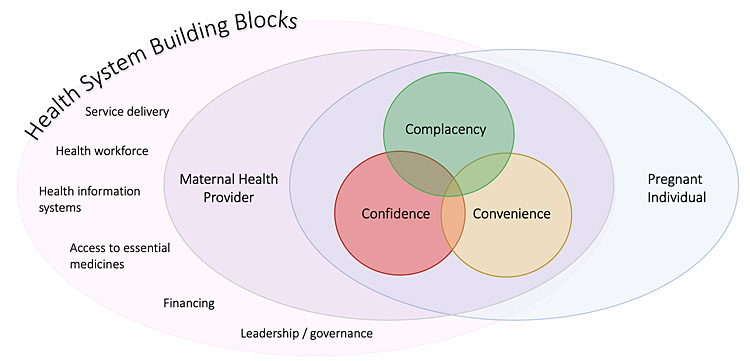

CHARACTERISTICS OF AN ENABLING HEALTH SYSTEM FOR THE MATERNAL HEALTH PROVIDER

Finally, it is important to address supporting health systems required for maternal health providers to successfully counsel patients on the recommended vaccines in pregnancy and ultimately increase vaccination rates. The WHO’s 2010 handbook on the building blocks of health systems describes six key building blocks that enable the work of the maternal health provider and provide a framework for factors that contribute to the capacity for health providers to both recommend and offer vaccines during prenatal visits: service delivery, health workforce, health information systems, access to essential medicines, financing, and leadership/governance.44 For instance, a study conducted in the United States, which included survey responses from members of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), found that common reasons for not offering the influenza vaccine to patients included inadequate reimbursement as well as lack of storage and handling facilities for vaccines.45 Similarly, in a German study including 867 gynecologists, time and effort needed to counsel pregnant patients on the influenza vaccine was the most commonly reported barrier to vaccine recommendation (26%), with billing restrictions as an additional barrier to recommendation (7.8%).46 In another study looking at the determinants of maternal immunization in developing countries, district health officers and maternal and child health coordinators across six district hospitals in Malawi were surveyed. Respondents reported vaccine stock shortages (36%), insufficient storage spaces (36%), and long wait times for patients (45%) as reasons that pregnant women do not receive the tetanus toxoid vaccine.47 Ultimately, systems for adequate financial reimbursement, provider education, health policy and leadership, as well as proper procurement, storage, and administration of vaccines are required to enable maternal health providers to increase maternal immunization.

CONCLUSION

Maternal health providers are a critical factor, and possibly the most important factor, in the decision of a pregnant individual to opt for maternal immunizations. Vaccine acceptance among the pregnant population is increased when a maternal health provider both recommends and offers a vaccine during pregnancy. Various other attributes of the patient–provider relationship play a role in vaccine acceptance and recommendation including knowledge of the pregnant person about vaccines during pregnancy, effective communication, and the trust relationship that has been built. Characteristics of the maternal health provider are also important including own existing biases, knowledge about the vaccine and public health policies, type of provider, and own vaccine acceptance. Finally, health systems in place can enable the discussion of vaccines and recommendations for vaccines by maternal health providers as well as make vaccines readily available to be offered. As maternal immunizations are expanded to play an increasingly important role in infectious disease prevention, resources must be available to enable maternal health providers to foster trust relationships with their patients and educate them on the vaccines, their safety and efficacy, and the critical role they play in promoting maternal immunizations.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- Maternal health providers should make vaccine recommendations AND offers, if possible, during prenatal visits following public health guidelines.

- Effective communication between the patient and maternal health provider as well as trust are key components to increasing acceptance of vaccinations.

- Increasing knowledge about the vaccines as well as health policies regarding vaccines in pregnancy may increase the maternal health provider’s capacity to provide a strong recommendation for vaccines during pregnancy.

- Health system components must be in place to enable maternal health providers to build relationships with their patients and take time to discuss and recommend vaccines during pregnancy.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors of this chapter declare that they have no interests that conflict with the contents of the chapter. Outside of this work, Dr Kachikis has been an unpaid consultant for GlaxoSmithKline and Pfizer. She has received grant support to her university from Merck and Pfizer.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

REFERENCES

WHO. Questions and Answers: COVID-19 vaccines and pregnancy. In: World Health Organization (ed.) Online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-FAQ-Pregnancy-Vaccines-2022.1. | |

Safety of Immunization during Pregnancy: a review of the evidence. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2014. Available from: http://www.who.int/vaccine_safety/publications/safety_pregnancy_nov2014.pdf. | |

Abu-Raya B, Maertens K, Edwards KM, et al. Global Perspectives on Immunization During Pregnancy and Priorities for Future Research and Development: An International Consensus Statement. Front Immunol 2020;11:1282. | |

Halasa NB, Olson SM, Staat MA, et al. Effectiveness of Maternal Vaccination with mRNA COVID-19 Vaccine During Pregnancy Against COVID-19-Associated Hospitalization in Infants Aged <6 Months – 17 States, July 2021 January 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022;71(7):264–70. | |

Stock SJ, Carruthers J, Calvert C, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 vaccination rates in pregnant women in Scotland. Nat Med 2022. | |

Amirthalingam G, Andrews N, Campbell H, et al. Effectiveness of maternal pertussis vaccination in England: an observational study. Lancet 2014;384(9953):1521–8. | |

Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices–United States, 2013–2014. MMWR Recommendations and reports: Morbidity and mortality weekly report Recommendations and reports 2013;62(Rr-07):1–43. | |

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Flu and Tdap Vaccination Coverage Among Pregnant Women. United States, 2021. Updated 7 October 2021. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/pregnant-women-apr2021.htm. | |

UK Health Security Agency. Pertussis vaccination programme for pregnant women update: vaccine coverage in England, July to September 2021. 2021 22 February 2022. Contract No.: 3. | |

Callahan AG, Coleman-Cowger VH, Schulkin J, et al. Racial disparities in influenza immunization during pregnancy in the United States: A narrative review of the evidence for disparities and potential interventions. Vaccine 2021;39(35):4938–48. | |

Kriss JL, Albert AP, Carter VM, et al. Disparities in Tdap Vaccination and Vaccine Information Needs Among Pregnant Women in the United States. Matern Child Health J 2019;23(2):201–11. | |

Bödeker B, Walter D, Reiter S, Wichmann O. Cross-sectional study on factors associated with influenza vaccine uptake and pertussis vaccination status among pregnant women in Germany. Vaccine 2014;32(33):4131–9. | |

Quattrocchi A, Mereckiene J, Fitzgerald M, et al. Determinants of influenza and pertussis vaccine uptake in pregnant women in Ireland: A cross-sectional survey in 2017/18 influenza season. Vaccine 2019;37(43):6390–6. | |

Lutz CS, Carr W, Cohn A, et al. Understanding barriers and predictors of maternal immunization: Identifying gaps through an exploratory literature review. Vaccine 2018;36(49):7445–55. | |

Kilich E, Dada S, Francis MR, et al. Factors that influence vaccination decision-making among pregnant women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2020;15(7):e0234827. | |

World Health Organization. Report of the Sage Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Geneva: WHO, 2014. | |

Morales KF, Menning L, Lambach P. The faces of influenza vaccine recommendation: A Literature review of the determinants and barriers to health providers' recommendation of influenza vaccine in pregnancy. Vaccine 2020;38(31):4805–15. | |

Vilca LM, Cesari E, Tura AM, et al. Barriers and facilitators regarding influenza and pertussis maternal vaccination uptake: A multi-center survey of pregnant women in Italy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2020;247:10–5. | |

Bartolo S, Deliege E, Mancel O, et al. Determinants of influenza vaccination uptake in pregnancy: a large single-Centre cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019;19(1):510. | |

Offeddu V, Tam CC, Yong TT, et al. Coverage and determinants of influenza vaccine among pregnant women: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2019;19(1):890. | |

Fleming JA, Munthali A, Ngwira B, et al. Maternal immunization in Malawi: A mixed methods study of community perceptions, programmatic considerations, and recommendations for future planning. Vaccine 2019;37(32):4568–75. | |

Arriola CS, Vasconez N, Bresee J, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and practices about influenza vaccination among pregnant women and healthcare providers serving pregnant women in Managua, Nicaragua. Vaccine 2018;36(25):3686–93. | |

Mayet AY, Al-Shaikh GK, Al-Mandeel HM, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and barriers associated with the uptake of influenza vaccine among pregnant women. Saudi Pharm J 2017;25(1):76–82. | |

Maurici M, Dugo V, Zaratti L, et al. Knowledge and attitude of pregnant women toward flu vaccination: a cross-sectional survey. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2016;29(19):3147–50. | |

Bettinger JA, Greyson D, Money D. Attitudes and Beliefs of Pregnant Women and New Mothers Regarding Influenza Vaccination in British Columbia. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2016;38(11):1045–52. | |

Li WF, Huang SY, Peng HH, et al. Factors affecting pregnant women's decisions regarding prenatal pertussis vaccination: A decision-making study in the nationwide Prenatal Pertussis Immunization Program in Taiwan. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 2020;59(2):200–6. | |

Ugezu C, Essajee M. Exploring patients' awareness and healthcare professionals' knowledge and attitude to pertussis and influenza vaccination during the antenatal periods in Cavan Monaghan general hospital. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2018;14(4):978–83. | |

Salmon DA, Dudley MZ, Glanz JM, et al. Vaccine hesitancy: Causes, consequences, and a call to action. Vaccine 2015;33(Suppl 4):D66–71. | |

Stark LM, Power ML, Turrentine M, et al. Influenza Vaccination among Pregnant Women: Patient Beliefs and Medical Provider Practices. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 2016;2016:3281975. | |

Maisa A, Milligan S, Quinn A, et al. Vaccination against pertussis and influenza in pregnancy: a qualitative study of barriers and facilitators. Public Health 2018;162:111–7. | |

Nganga SW, Otieno NA, Adero M, et al. Patient and provider perspectives on how trust influences maternal vaccine acceptance among pregnant women in Kenya. BMC Health Services Research 2019;19(1):747. | |

Fleming JA, Baltrons R, Rowley E, et al. Implementation of maternal influenza immunization in El Salvador: Experiences and lessons learned from a mixed-methods study. Vaccine 2018;36(28):4054–61. | |

Dudley MZ, Limaye RJ, Salmon DA, Omer SB, O'Leary ST, Ellingson MK, et al. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Maternal Vaccine Knowledge, Attitudes, and Intentions. Public Health Rep 2021;136(6):699–709. | |

Donaldson B, Jain P, Holder BS, et al. What determines uptake of pertussis vaccine in pregnancy? A cross sectional survey in an ethnically diverse population of pregnant women in London. Vaccine 2015;33(43):5822–8. | |

Praphasiri P, Ditsungneon D, Greenbaum A, et al. Do Thai Physicians Recommend Seasonal Influenza Vaccines to Pregnant Women? A Cross-Sectional Survey of Physicians' Perspectives and Practices in Thailand. PLoS One 2017;12(1):e0169221. | |

Gesser-Edelsburg A, Shir-Raz Y, Hayek S, et al. Despite awareness of recommendations, why do health care workers not immunize pregnant women? Am J Infect Control 2017;45(4):436–9. | |

Wilcox CR, Calvert A, Metz J, et al. Determinants of Influenza and Pertussis Vaccination Uptake in Pregnancy: A Multicenter Questionnaire Study of Pregnant Women and Healthcare Professionals. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2019;38(6):625–30. | |

Loubet P, Nguyen C, Burnet E, et al. Influenza vaccination of pregnant women in Paris, France: Knowledge, attitudes and practices among midwives. PLoS One 2019;14(4):e0215251. | |

Kang BS, Lee SH, Kim WJ, et al. Influenza vaccination during pregnancy and influencing factors in Korea: A multicenter questionnaire study of pregnant women and obstetrics and gynecology doctors. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2021;21(1):511. | |

Tong A, Biringer A, Ofner-Agostini M, et al. A cross-sectional study of maternity care providers' and women's knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours towards influenza vaccination during pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2008;30(5):404–10. | |

Maertens K, Braeckman T, Top G, et al. Maternal pertussis and influenza immunization coverage and attitude of health care workers towards these recommendations in Flanders, Belgium. Vaccine 2016;34(47):5785–91. | |

Mohammed H, Clarke M, Koehler A, et al. Factors associated with uptake of influenza and pertussis vaccines among pregnant women in South Australia. PLoS One 2018;13(6):e0197867. | |

Arnold LD, Luong L, Rebmann T, et al. Racial disparities in U.S. maternal influenza vaccine uptake: Results from analysis of Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) data, 2012–2015. Vaccine 2019;37(18):2520–6. | |

World Health Organization. Monitoring the Building Blocks Of Health Systems: A Handbook of Indicators and their Measurement Strategies. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2010. | |

Kissin DM, Power ML, Kahn EB, et al. Attitudes and practices of obstetrician-gynecologists regarding influenza vaccination in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2011;118(5):1074–80. | |

Böhm S, Röbl-Mathieu M, Scheele B, et al. Influenza and pertussis vaccination during pregnancy – attitudes, practices and barriers in gynaecological practices in Germany. BMC Health Serv Res 2019;19(1):616. | |

Pathirana J, Nkambule J, Black S. Determinants of maternal immunization in developing countries. Vaccine 2015;33(26):2971–7. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards program CLICK HERE)