This chapter should be cited as follows:

Oyelese Y, Perez M, et al., Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.419203

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Obstetrics Module

Volume 18

Ultrasound in obstetrics

Volume Editors:

Professor Caterina M (Katia) Bilardo, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam and University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands

Dr Valentina Tsibizova, PREIS International School, Florence, Italy

Chapter

Ultrasound Evaluation of the Placenta, Umbilical Cord and Membranes: Normal and Abnormal Findings

First published: August 2025

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

The placenta and umbilical cord play a pivotal role in fetal wellbeing, serving as the lifeline that supports the developing fetus.1 Ultrasound is the primary – and often the only – tool for assessing these critical structures during pregnancy.2 Unfortunately, the focus of most obstetric imaging is almost exclusively the fetus, leaving the placenta and cord relatively underexamined.1,3,4,5 This oversight can have significant consequences, as undiagnosed abnormalities of the placenta or umbilical cord can lead to severe complications for both the mother and the fetus.1,2,3,4 Indeed, issues related to the placenta and cord are among the leading causes of stillbirth, with one large study attributing 23% of stillbirths to cord abnormalities.6 In addition, these conditions increase the risk for long-term sequelae in the offspring, including cerebral palsy.7,8 Many of these abnormalities are detectable by ultrasound, and adverse outcomes resulting from them are preventable by instituting appropriate management plans.

Those who perform obstetric imaging often encounter placental or umbilical cord abnormalities with which they may be unfamiliar, making it challenging to interpret the findings, assess the associated risks and determine the appropriate course of action to mitigate perinatal or maternal morbidity and mortality.2,9,10,11,12 This chapter is designed to equip sonographers and physicians with the knowledge to assess accurately the placenta, umbilical cord and membranes during prenatal ultrasound. It explores the normal and abnormal appearances of these structures, highlights key abnormalities that can be detected and discusses their clinical implications, and describes the management pathways when abnormal findings occur, providing a comprehensive guide to optimizing prenatal care and improving outcomes.

THE PLACENTA

Development

The placenta is a unique disc-shaped temporary organ that is attached to the uterine wall and forms the interface between the mother and the fetus. The placenta’s primary functions include facilitating the exchange of oxygen, nutrients and waste products between the mother and fetus. It also is responsible for producing hormones essential for maintaining pregnancy and acts as a protective barrier against harmful substances and organisms.

The maternal surface of the placenta or basal plate is derived from the decidua basalis and is in direct contact with the maternal endometrium, anchoring the placenta to the uterine wall. Nitabuch’s fibrinoid layer, also known as the uteroplacental fibrinoid, is an uninterrupted layer that separates trophoblastic cells from decidual cells, marking the maternofetal border.

The fetal surface, or chorionic plate, is a segment of the continuous chorionic tissue surrounding the fetus. Unlike the chorion laeve (fetal membranes), the chorionic plate has a thicker connective tissue layer containing fetal vessels that branch from the umbilical cord and spread across the fetal surface.

Between the chorionic plate (fetal surface) and the basal plate (maternal surface) lies the villous parenchyma, which consists of fetally-derived chorionic villi. These villi are immersed in the intervillous space, where maternal blood circulates. Gas exchange, as well as the transfer of nutrients and waste products between maternal and fetal circulations, occurs at the level of the chorionic villi.

The umbilical cord serves as the connecting stalk, acting as a conduit for fetal vessels between the placenta and the fetus.

Normal ultrasound appearance of the placenta

Placental characteristics by trimester: thickness, echogenicity and location

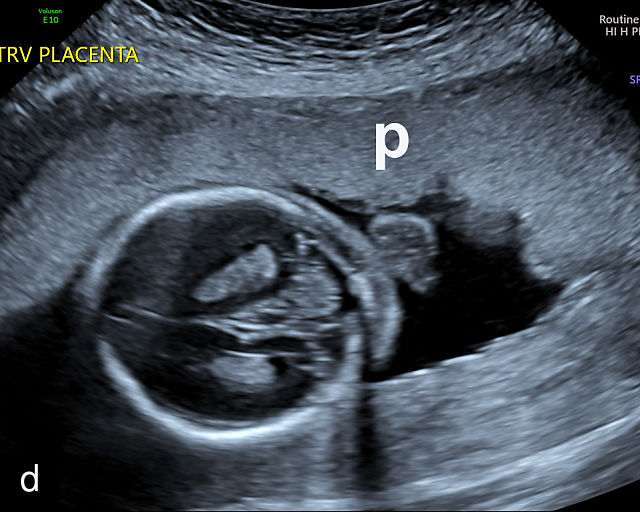

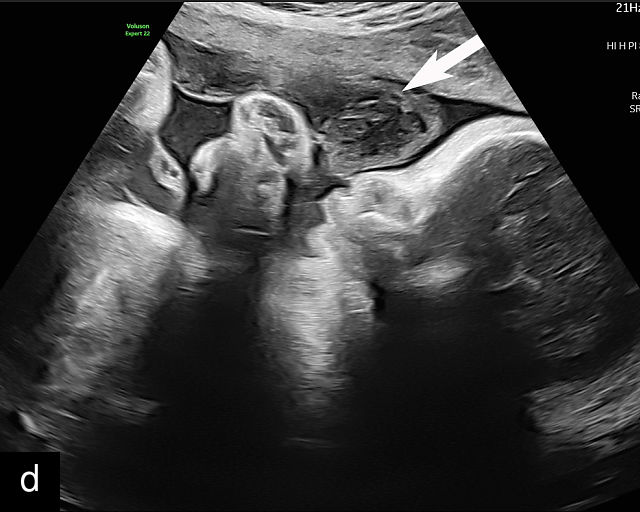

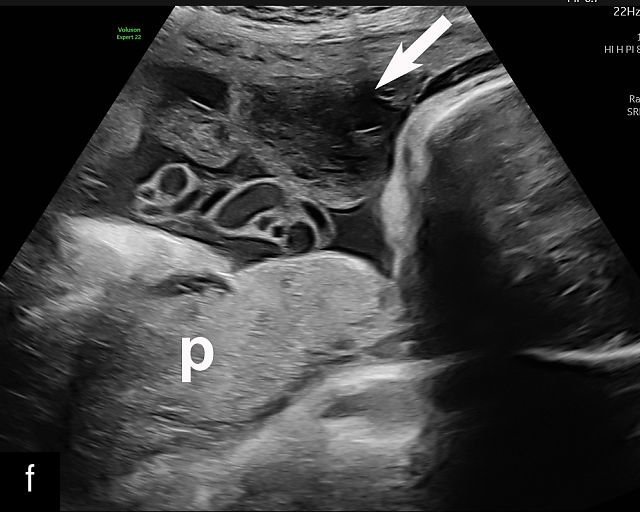

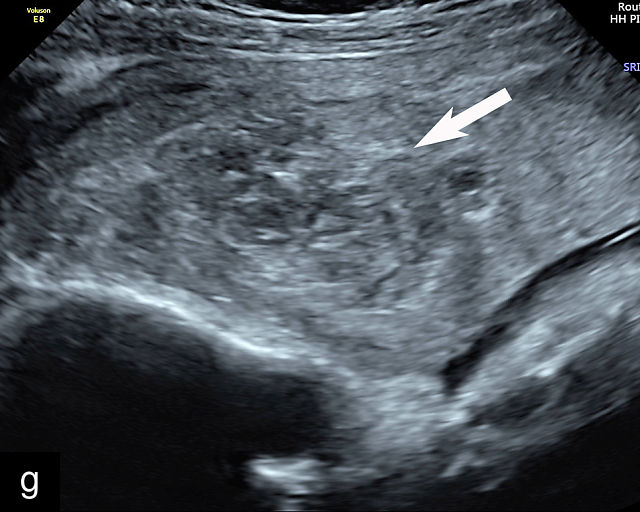

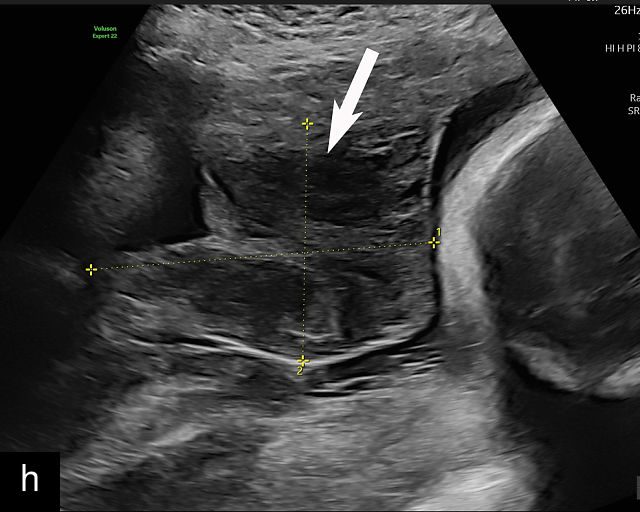

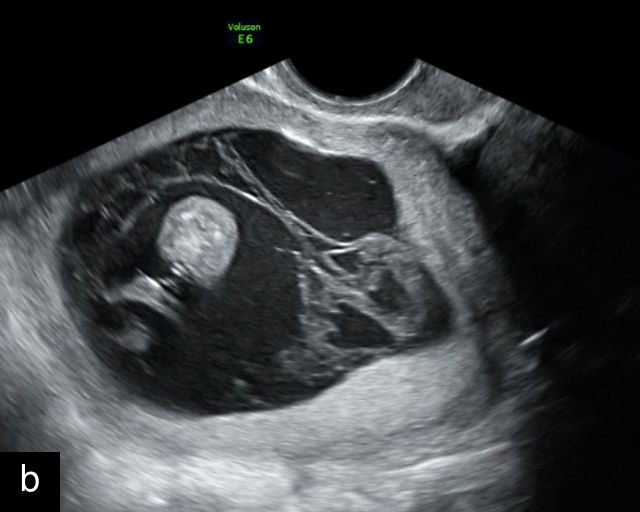

In the early first trimester, trophoblastic tissue appears as an echogenic ring encircling the gestational sac (Figure 1a). By the late first trimester, the placenta becomes recognizable as a distinct structure on ultrasound (Figure 1b). Initially, it presents as a homogeneous echogenic mass (Figure 1b–d) but undergoes progressive differentiation, becoming more heterogeneous as pregnancy advances from the second to third trimester (Figure 1e–g). By the third trimester, cotyledons become discernible, and in the late third trimester, calcifications frequently appear basally and around the cotyledons (Figure 1g).

1

Ultrasound images of development of the placenta (P/p). (a) Trophoblastic tissue appearing as an echogenic ring surrounding the gestational sac at 6 weeks' gestation. (b) Placenta at 12 weeks has become a discrete, uniformly echogenic mass. (c) Placenta at 17 weeks. (d) Placenta at 20 weeks. (e) Placenta at 27 weeks. (f) Placenta at 33 weeks. Increasingly, differentiation and heterogeneous appearance is seen, with demarcation of the cotyledons. Basal calcifications are beginning to appear. (g) Placenta at 40 weeks, showing a distinctly heterogeneous appearance, with clear demarcation of the cotyledons and presence of calcifications.

The placenta can be located anteriorly, posteriorly, fundally or laterally or in a low-lying position, including placenta previa (covering or near the internal cervical os). A low-lying placenta or placenta previa is common before 20 weeks, with over 90% resolving before term. Most placentas covering the internal os in early pregnancy will migrate away by 20 weeks; therefore, the terms 'placenta previa' or 'low-lying placenta' should not be used before 18 weeks.

Placental thickness increases with gestational age, averaging approximately 1 mm per week. Subchorionic hematomas, commonly seen in the first and second trimesters, are typically of little or no clinical significance and most often resolve as pregnancy progresses. Additionally, hypoechoic areas known as placental lakes are frequently observed and generally hold no clinical significance.13

Systematic approach to sonographic placental examination

Ultrasound identification of the placenta was first described by Gottesfeld and associates in 1966.14 Examination of the placenta is now a part of routine obstetric ultrasound. However, this assessment is typically limited to determining the placenta’s location, particularly in relation to the internal os, and, in some cases, identifying the site of umbilical cord insertion.2 More detailed evaluations may include the number of placental lobes. Overall, examination of the placenta has been limited by the absence of a standardized approach.2

Recently, Hernandez-Andrade and colleagues proposed a systematic method for sonographic evaluation of the placenta, highlighting the importance of assessing more than just placental location and cord insertion.² Their approach includes performing a sagittal sweep of the entire placenta, moving from side to side and top to bottom, to ensure a thorough evaluation.

Their method involves evaluating four key placental regions:

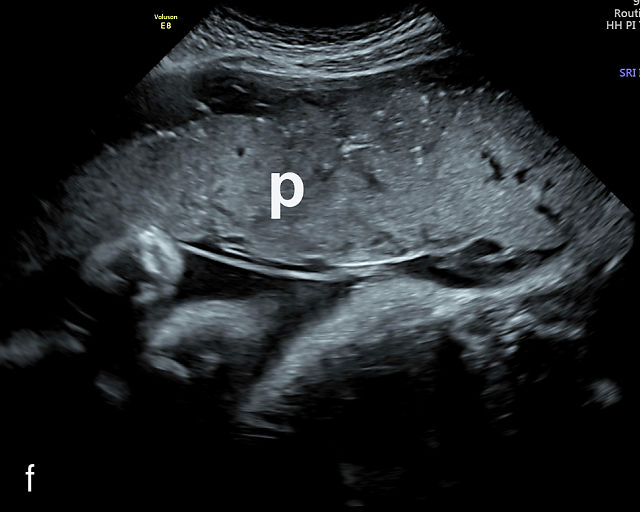

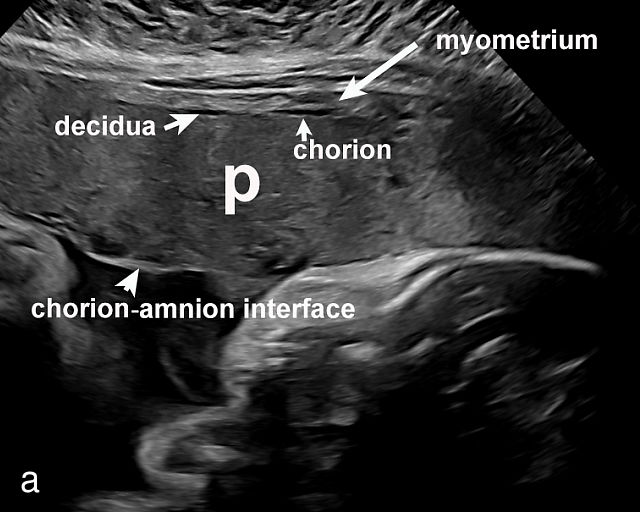

- The uterine wall (myometrium) and the decidua/chorion interface – The outermost layer, the uterine wall or myometrium, appears as a gray area with varying thickness (Figure 2a) depending on placental location. The myometrium is generally thicker when the placenta is located in the upper uterus or fundus. Just beneath the myometrium lies the decidua, a hypoechoic (black) layer where the spiral arteries develop.

- The amnion–chorion (or chorion–amnion) interface – The amnion, the innermost fetal membrane, is more echogenic and appears as a gray line, while the underlying chorion is slightly less echogenic. This interface is important for identifying abnormalities in the fetal surface of the placenta.

- The placental body – The main mass of the placenta, where most abnormalities are detected. The texture, thickness and uniformity of the placental body should be carefully examined for any irregularities.

- The umbilical cord insertion (Figure 2b,c) and placental margin (Figure 2d) – Special attention should be paid to the site at which the umbilical cord or vessels insert into the placenta, as well as the marginal regions of the placenta, to identify potential abnormalities.

2

(a) Transabdominal grayscale ultrasound image of the placenta showing the four key placental regions: the myometrium (gray area), decidua (black line), chorion (light gray thin line), placental body (p), and the chorion–amnion interface. (b) Grayscale ultrasound image of the umbilical cord insertion into the placenta. (c) Same view as in (b) but with color Doppler applied. (d) Normal placental edge (arrow), which is a common location for placental lakes. (e) Rolled placental edges (arrows) in circumvallate placenta (p).

Hernandez-Andrade and colleagues assert that most placental abnormalities can be accurately identified using gray-scale ultrasound alone, but color Doppler can be a valuable tool in distinguishing between certain lesions.2,15 By following this structured approach, these authors propose that the majority of placental and cord abnormalities can be effectively recognized, leading to improved diagnostic accuracy and better prenatal care.2

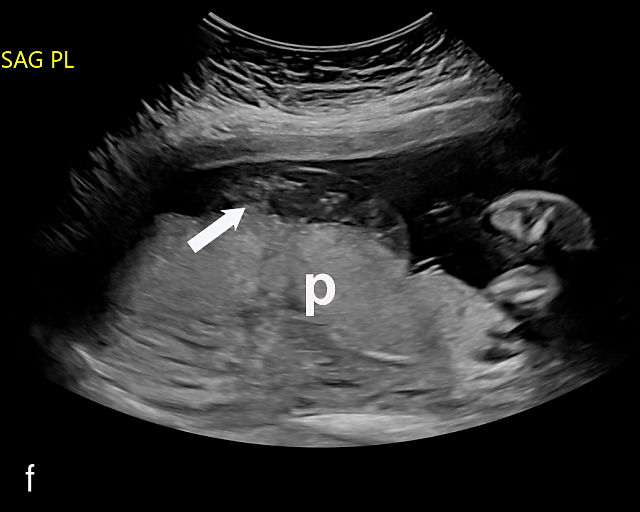

Placental lakes

Placental lakes are hypoechoic regions within the placenta and are the most common finding on ultrasound of the placenta (Figure 3; Video 1).2,9,13,16 They are surrounded by placental tissue of normal echogenicity.16 Some reports specify that hypoechoic areas should be at least 2 cm in size to qualify as lakes.13,17 On grayscale ultrasound, swirling of blood can be observed in lakes (Video 1). Low-velocity flow can be demonstrated using sensitive Doppler techniques. Lakes tend to be located in the center of placental cotyledons or under the chorionic plate (Figure 3).16 Other common locations are at the placental edge and between lobes in a bilobed placenta where they may be very large. Lakes tend to fluctuate in size over time. Several studies have found that placental lakes are not associated with an increase in adverse pregnancy outcome, regardless of size and number.13,18,19 However, one study found an increased risk of small-for-gestational age fetuses with larger placental lakes.20 Lakes must be differentiated from lacunae, which contain high-velocity blood flow and are associated with placenta accreta spectrum.16

3

(a–f) Placental lakes. Multiple hypoechoic spaces present in placenta (p), surrounded by placental tissue of normal echogenicity. Arrows in (e) and (f) indicate lakes.

1

(a–c) Placental lakes. Multiple hypoechoic spaces present in placenta, surrounded by placental tissue of normal echogenicity. The spaces demonstrate low-velocity swirling, visible on grayscale ultrasound.

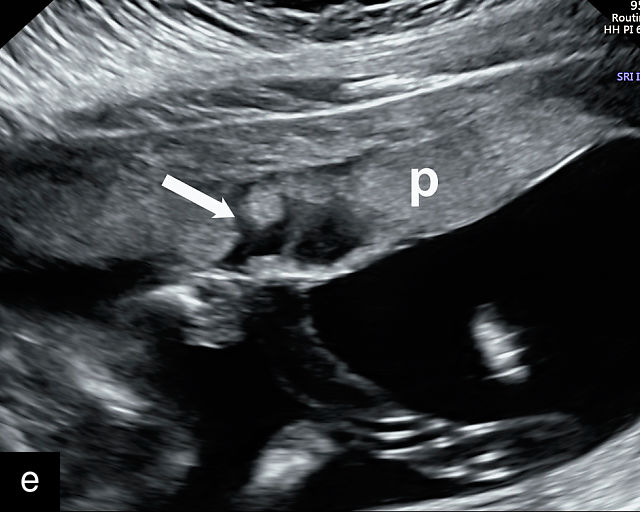

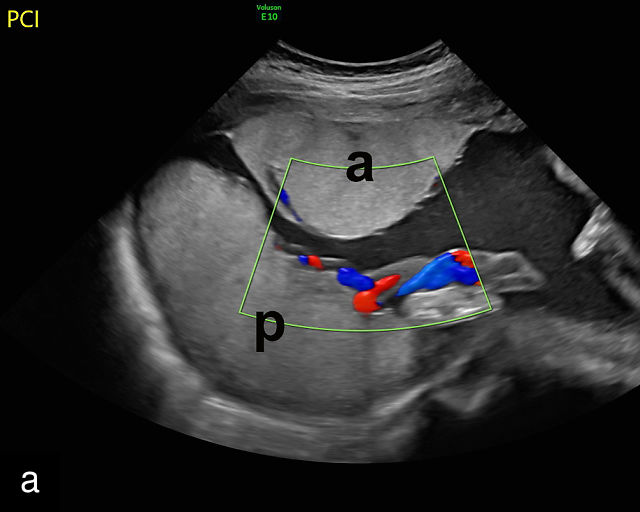

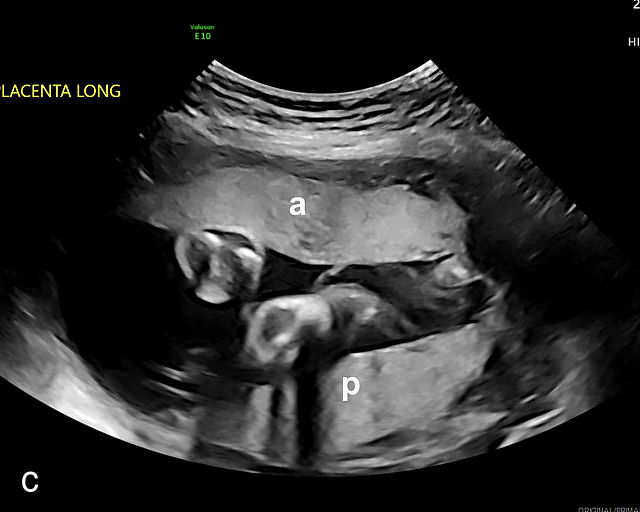

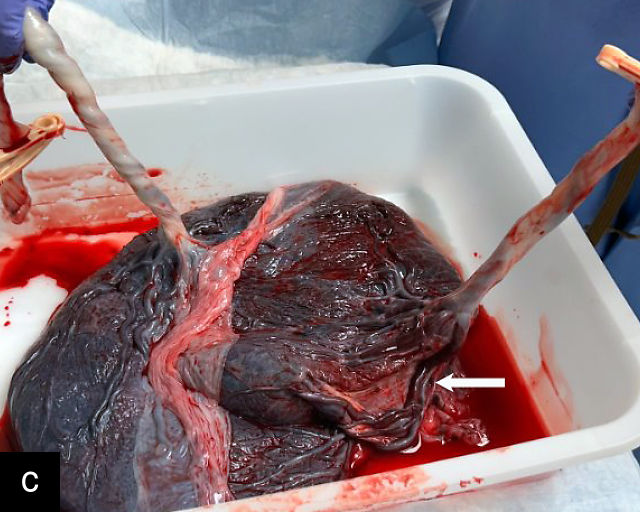

Accessory placental lobes

While most placentas consist of a single disc with several cotyledons, some placentas may have two or more separate lobes. These variations can include a bilobate placenta, where two lobes of roughly equal size are present, or a main placental body accompanied by one or more smaller accessory or succenturiate lobes (Figure 4).21,22,23,24 The cord insertions in these pregnancies are often velamentous or marginal, and blood vessels always traverse the membranes between the placental lobes. When these connecting vessels pass over the cervix, the condition is classified as Type- 2 or Type- 3 vasa previa.25,26,27,28,29,30

4

Accessory placental lobes. (a) Color Doppler transabdominal ultrasound image depicting a bilobed placenta with an anterior (a) and posterior (p) lobe, into which the cord inserts. (b) Grayscale ultrasound with color flow Doppler showing a bilobed placenta with anterior (a) and posterior (p) lobes. Color flow Doppler shows unprotected fetal vessels traversing the membranes between the lobes (arrow). (c) Grayscale ultrasound showing a bilobed placenta with anterior (a) and posterior (p) lobes.

The sonographic features of a bilobed or succenturiate-lobed placenta include the presence of two distinct placental masses, typically one anterior and the other posterior, which may vary in size or be of equal size.21,22,23,24,26,31,32,33 These masses are connected by blood vessels, which can be visualized using color flow Doppler (Figure 4).28

It is crucial to confirm that the masses are truly separate and not connected as part of a single lateral placenta, which may be mistaken for a bilobate placenta. Additionally, careful scanning should verify that both masses share similar echogenicity to distinguish true placental tissue from other structures such as subchorionic hematomas, myometrial contractions or uterine fibroids, which can mimic accessory lobes. Prominent placental lakes may also be observed between the lobes.23,26

The placental cord insertion in these cases is often velamentous and may be located between the placental lobes (Figure 4b; Video 2). In rare cases, furcate insertion, in which the cord vessels branch before reaching the placental tissue, between the lobes has been reported.24

2

Accessory placental lobes. (a) Grayscale (left) and color flow Doppler (right) ultrasound of bilobed placenta with cord insertion between the placental lobes. The cord insertion is marginal into the anterior lobe and unprotected vessels run through the membranes for a short distance into the posterior placental lobe. (b) Grayscale ultrasound showing a bilobed placenta.

Pregnancies conceived via assisted reproductive techniques, particularly in-vitro fertilization, are at increased risk of developing placentas with accessory lobes.22 Bilobate placentas have also been linked to an elevated risk of pre-eclampsia, though risks for small-for-gestational-age infants and preterm birth were not significantly increased.22

In most cases, pregnancies with accessory lobes have favorable outcomes in the absence of vasa previa. However, because accessory lobes are strongly associated with vasa previa, transvaginal ultrasound with color Doppler imaging is recommended whenever they are identified.3,4,25,28,34,35,36

At delivery, it is critical to examine the placenta thoroughly to ensure that it is complete and that no lobes have been retained. Retained accessory lobes can lead to postpartum hemorrhage, a potentially life-threatening complication.22

Placental grading

Placental grading was introduced by Grannum et al. as a method for assessing fetal lung maturity.37 They classified the sonographic appearance of the placenta into four grades. Grade 0 is characterized by a smooth chorionic plate with a uniform, homogeneous texture. Grade I shows mild undulations of the chorionic plate with scattered echogenic areas within the placental texture. Grade II is marked by linear hyperechoic calcifications within the basal plate (Figure 1f). Grade III features extensive calcifications distributed throughout the contours of the cotyledons (Figure 1g).

However, Quinlan and colleagues found no strong correlation between placental grading and fetal lung maturity.38 Their study reported that only 5% of pregnancies with confirmed fetal pulmonary maturity on amniotic fluid analysis had a Grade-III placenta. Additionally, placental Grade III on ultrasound incorrectly predicted fetal pulmonary maturity in 42% of cases. Another study found that, even beyond 40 weeks of gestation, only 20% of pregnancies exhibited a Grade-III placenta.39 Maternal smoking has been associated with Grade-III placentas.40

Subsequently, Vintzileos and colleagues proposed incorporating placental grading into a modified biophysical profile to assess fetal wellbeing.41,42 However, placental grading is no longer considered a primary tool for fetal assessment, partly due to poor inter- and intraobserver reliability in ultrasound interpretation.43,44,45 In addition, placental grading alone is a poor predictor of adverse perinatal outcomes.45,46 Despite this, some studies have suggested that the presence of a Grade-III placenta before term may be associated with an increased risk of adverse perinatal outcome including stillbirth.47,48 Therefore, when a Grade-III placenta is identified on ultrasound before 37 weeks, closer fetal monitoring may be warranted.

Abnormal placental findings

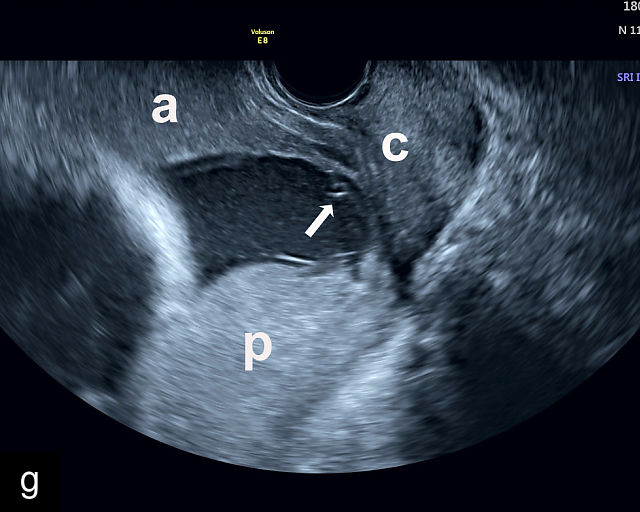

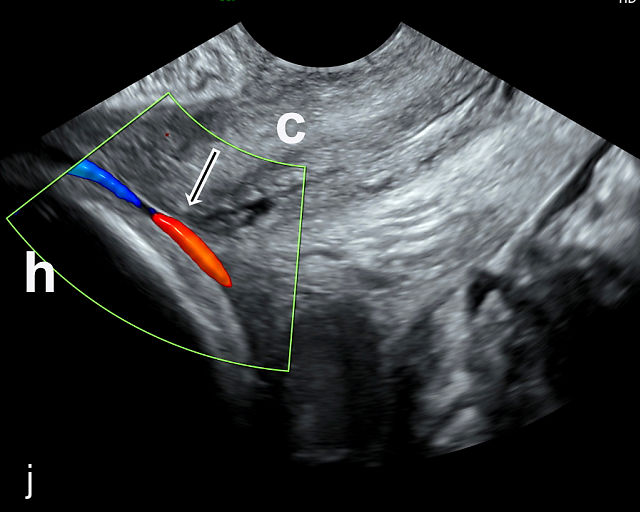

Placenta previa and low-lying placenta

In most pregnancies, the placenta implants in the upper part of the uterus. However, when the placenta implants in the lower uterine segment and overlies the cervix, it results in a condition called placenta previa, meaning the placenta is positioned ahead of the fetus in the birth canal.49 This positioning poses a serious risk during labor, as cervical dilation can cause premature placental separation, leading to severe, life-threatening bleeding for the pregnant patient.50,51 To prevent this hemorrhage, patients with placenta previa must be delivered by cesarean section before the onset of labor.51 Placenta previa complicates approximately 0.4% (1 in 250) of pregnancies at delivery.52 The strongest risk factor for placenta previa is a history of prior cesarean delivery.53,54,55 Maternal smoking, advanced maternal age and assisted reproductive technologies are also strong risk factors for placenta previa.56,57,58,59

Historically, placenta previa was most often identified in the early third trimester when patients presented with painless vaginal bleeding.49,60,61 However, with the widespread use of obstetric ultrasound in the second trimester, nearly all cases of placenta previa are now diagnosed incidentally in asymptomatic patients during routine scans. Notably, approximately 90% of placenta previa cases diagnosed in the second trimester will resolve by term due to placental ‘migration’ as the uterus grows.51,61,62,63,64,65 Thus, when placenta previa is diagnosed in the second half of pregnancy, the patient should have an examination close to delivery to determine whether the placenta previa is persistent or whether it has resolved. Generally, when a placenta previa is found at 20 weeks, a repeat ultrasound should be performed at about 32 weeks. In cases that persist at 32 weeks, a repeat scan should be performed around 36 weeks of gestation.66

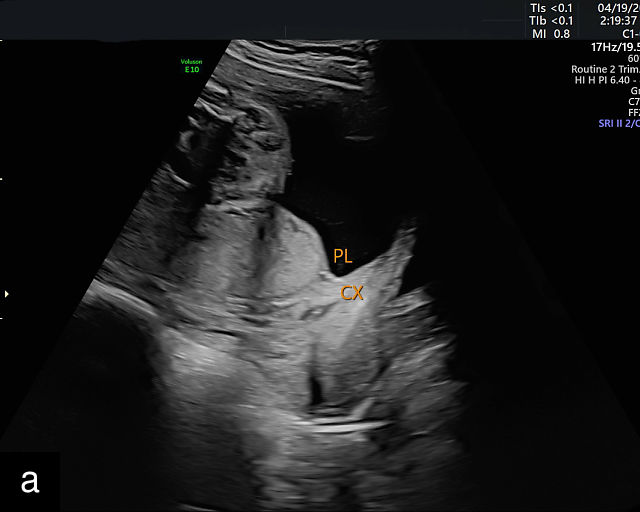

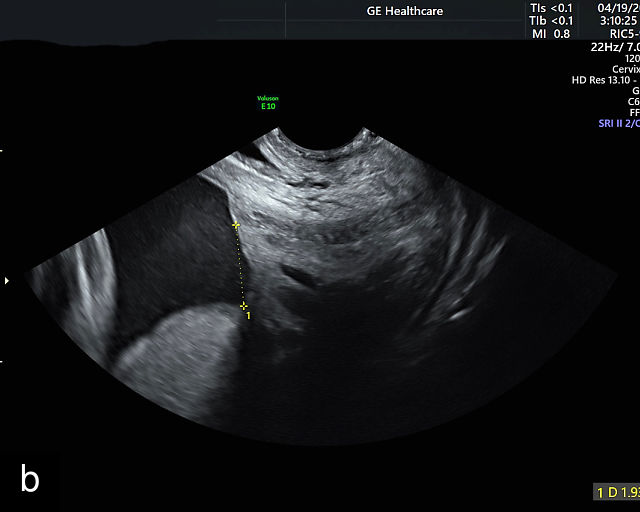

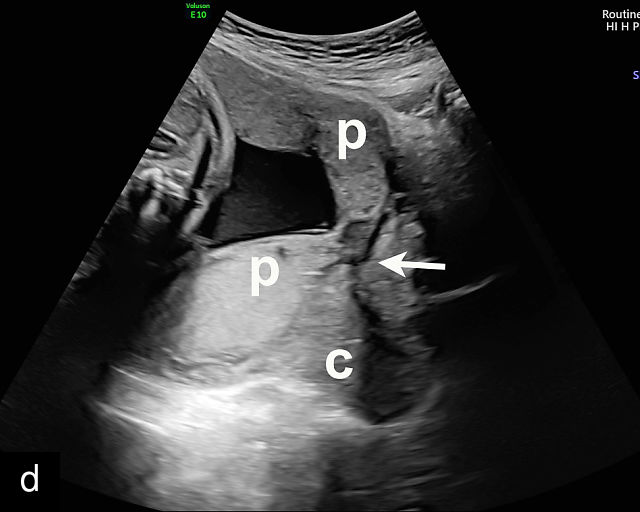

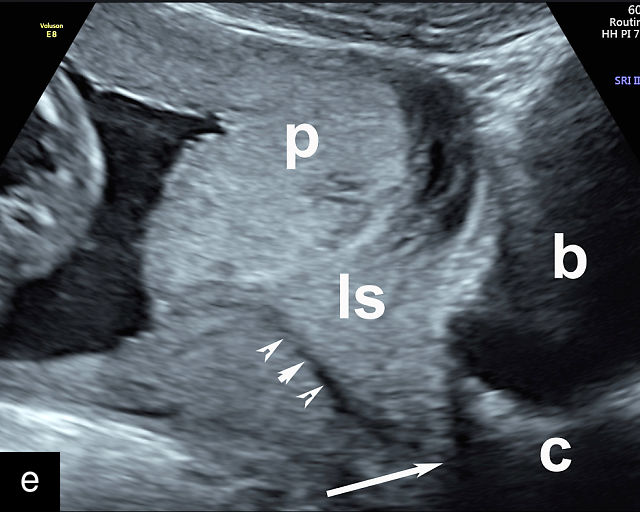

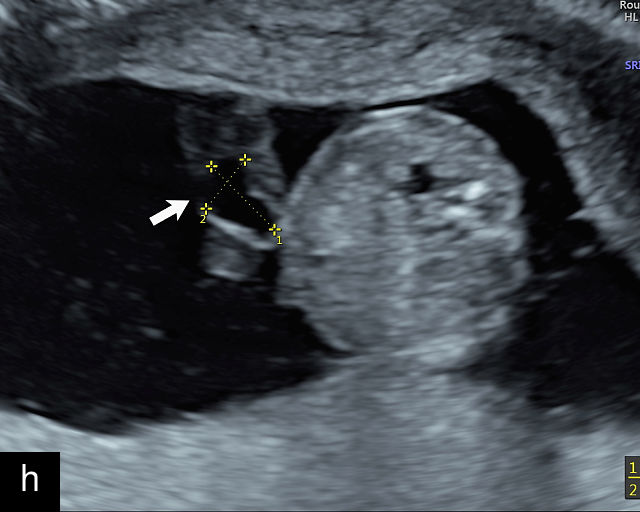

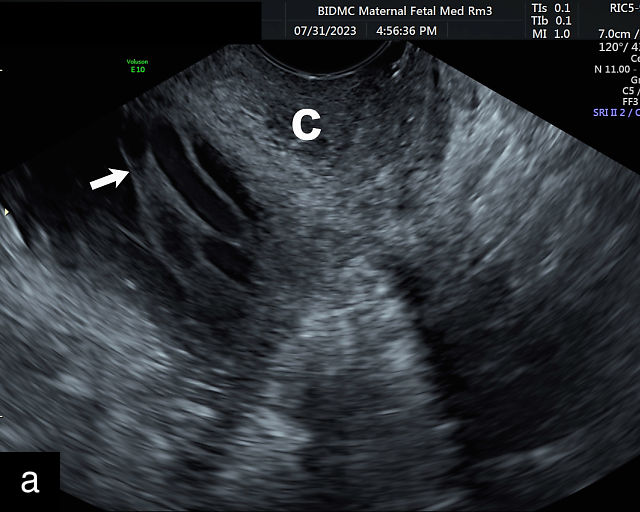

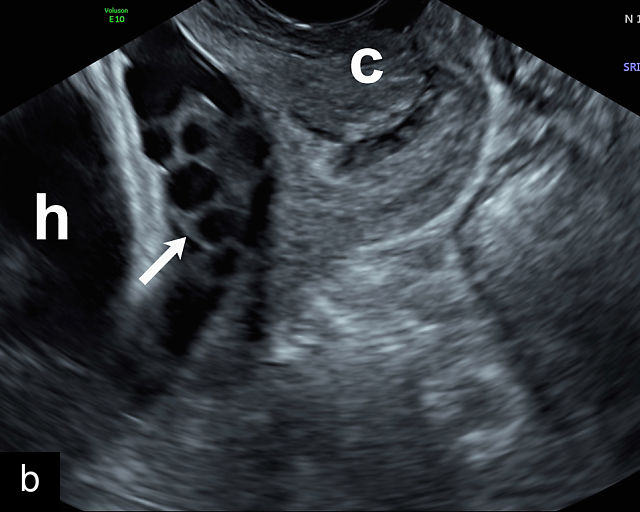

In the past, placenta previa was classified as complete, partial, marginal or low-lying.50,61 However, with advancements in ultrasound technology allowing precise assessment of the relationship between the placenta and the internal cervical os, the classification has been simplified.67 Placenta previa now refers to cases in which the placenta overlies the internal os to any degree, while low-lying placenta describes cases in which the lower placental edge lies within 2 cm of the internal os (Figure 5).51,66,67

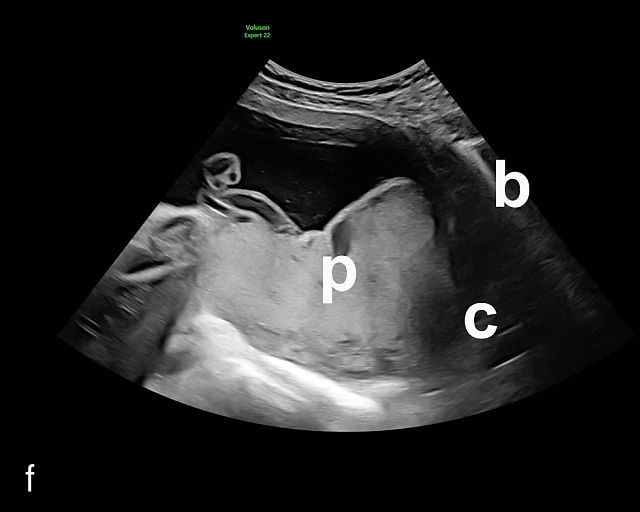

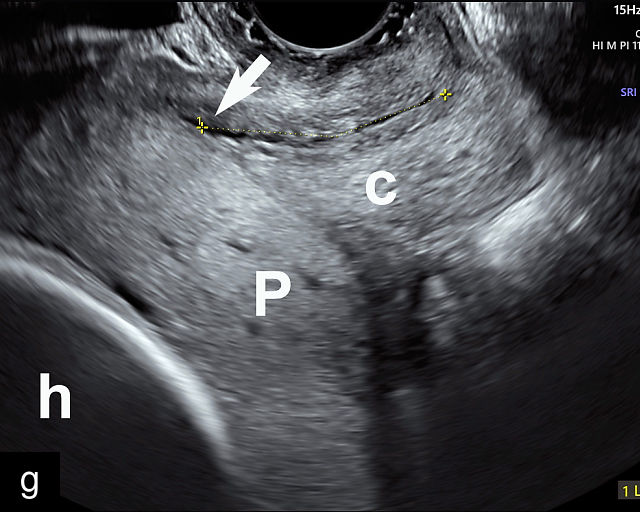

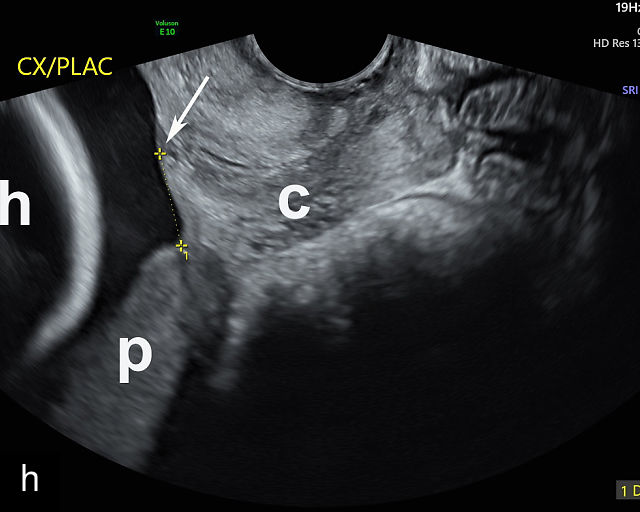

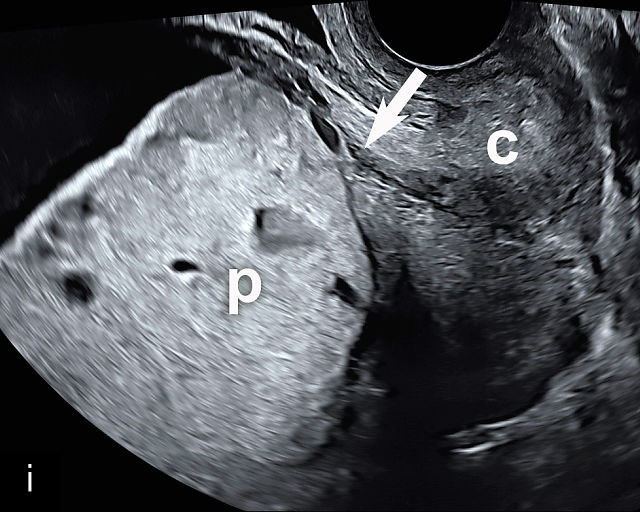

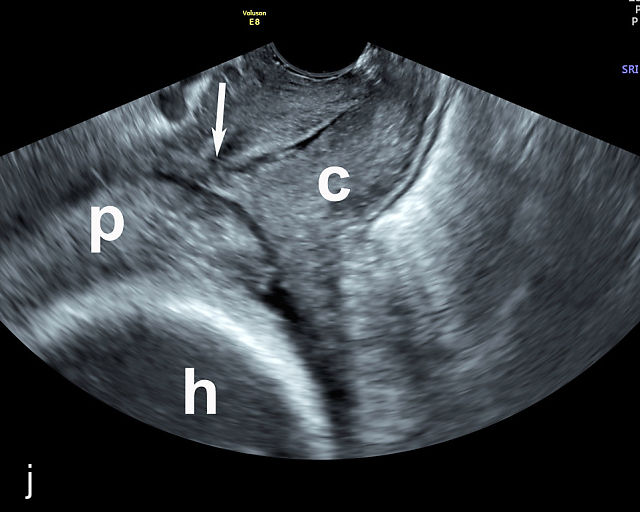

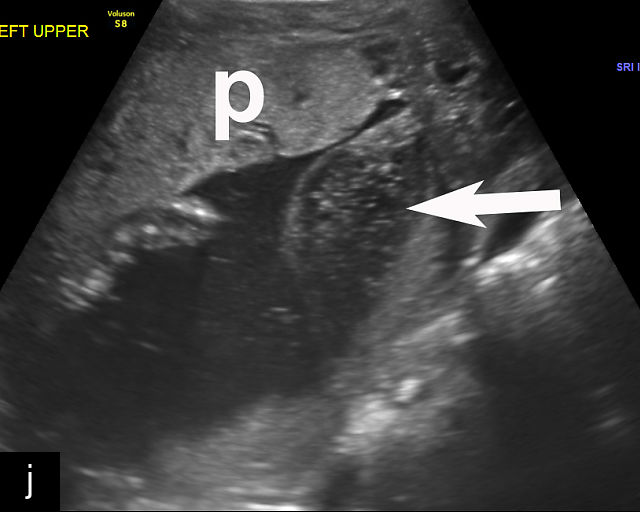

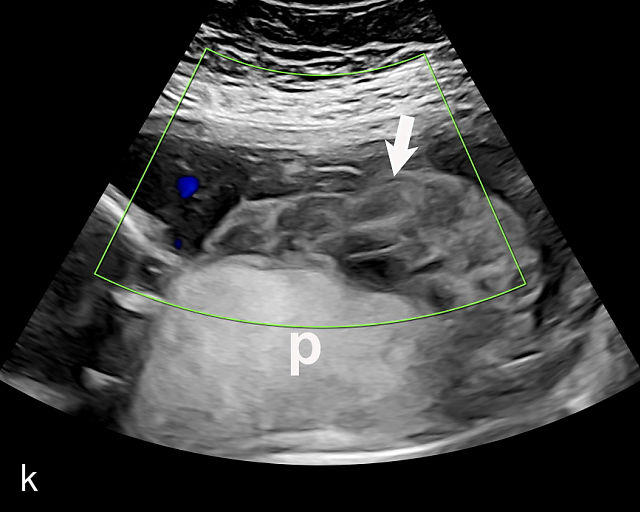

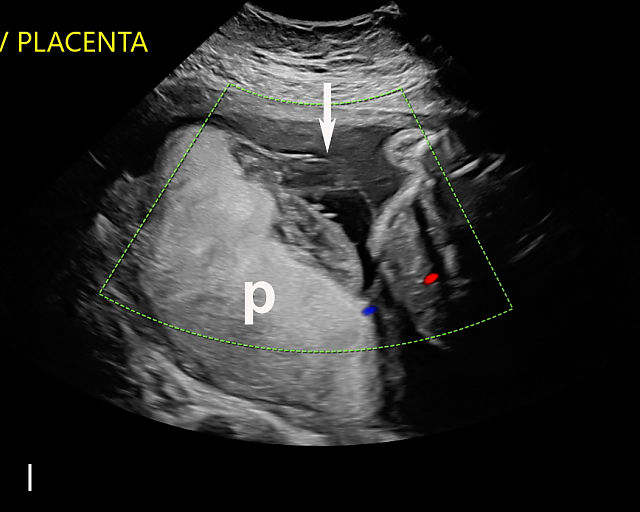

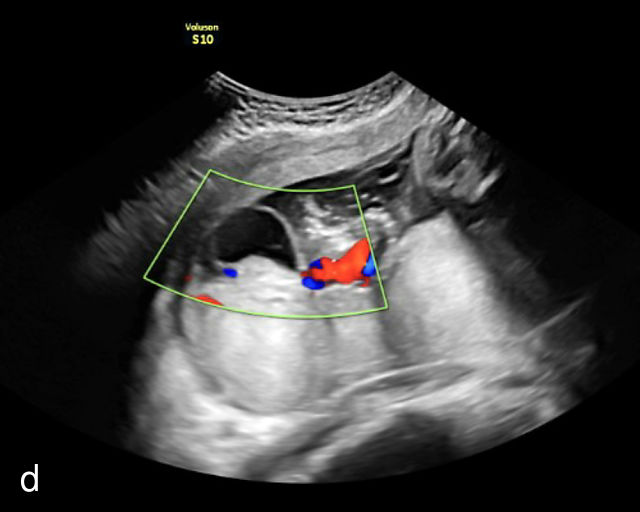

5

Placenta previa and low-lying placenta. (a) Transabdominal grayscale ultrasound image suspicious for placenta previa. The placenta (PL) appears to overlie the internal cervical os (CX). Note the time stamp: 2:19:37. (b) Transvaginal ultrasound of the same patient taken approximately 50 minutes later. Note the time stamp: 3:10:25. The internal os and the lower placental edge are both clearly seen, and the placenta does not overlie the internal os. Because the lower placental edge is 1.93 cm from the internal os, it will likely resolve by the third trimester. (c) Transabdominal grayscale ultrasound of placenta previa. The placenta (p) covers the cervix, but the cervix, especially the internal os, cannot be visualized due to shadowing. (d) Transabdominal grayscale ultrasound of placenta previa. The placenta (p) covers the cervix (c) but shadowing obscures adequate visualization. The internal os is indicated by the arrow. (e) False-positive image of placenta previa on transabdominal grayscale ultrasound. The bladder (b) is full, pushing the anterior and posterior walls of the lower uterine segment (ls) together making it appear that the placenta (p) overlies the internal os of the cervix. In reality, the line depicted by the arrowheads is where the anterior and posterior walls of the lower segment are in proximity to each other. The cervix is much lower and is obscured by shadowing (c). (f) Transabdominal grayscale ultrasound image of placenta previa. The placenta (p) covers the cervix (c), but the cervix, especially the internal os, cannot be visualized due to shadowing. b, bladder. (g) Transvaginal grayscale ultrasound image of placenta previa. The placenta (p) completely covers the internal os (arrow) of the cervix (c). The internal os can be seen clearly. h, fetal head. (h) Transvaginal grayscale ultrasound image of posterior low-lying placenta (p). The lower placental edge is clearly seen and is 1.56 cm from the internal os (arrow) of the cervix (c). The placental edge and the internal os are clearly seen. h, fetal head. (i) Transvaginal grayscale ultrasound image of a posterior placenta previa (p). The internal cervical os is clearly seen (arrow). c, cervix. (j) Transvaginal grayscale ultrasound image of an anterior placenta previa (p). The internal cervical os is clearly seen (arrow). c, cervix; h, fetal head. (k) Transvaginal grayscale ultrasound image of a posterior placenta that was thought to be low-lying on transabdominal sonography but could not be adequately assessed. This examination clearly shows the lower edge of the placenta (p) to be 2.18 cm from the internal os (arrow) of the cervix, firmly establishing that the placenta is not low-lying and allowing the patient to undergo labor safely and deliver vaginally. c, cervix. (l) Transvaginal grayscale ultrasound image of placenta previa. The placenta (p) completely covers the internal os (arrow) of the cervix (c). The internal os can be seen clearly.

This distinction is critical in determining the mode of delivery.49,51 All patients with placenta previa persisting into late pregnancy require cesarean delivery to avoid complications such as severe bleeding.50,60,61 Studies suggest that patients with a lower placental edge located more than 1 cm from the internal os may safely attempt a vaginal delivery without a significant increase in bleeding risk.68,69,70,71

In patients with placenta previa and one or more prior cesarean deliveries, careful evaluation is necessary to rule out placenta accreta spectrum disorders, in which the placenta abnormally adheres to or implants deeply into the uterine wall.50,60

Most cases of placenta previa will be suspected prenatally by transabdominal ultrasound.49 However, this approach has several limitations and may be inaccurate.72,73,74 because the relationship between the placenta and the internal cervical os may be difficult to assess by transabdominal ultrasound.72,73,74 The bladder may be full, pushing the anterior and posterior walls of the lower uterine segment together, falsely creating the impression of a placenta previa (Figure 5e).61 There may be considerable shadowing, including by the fetal presenting part, which may limit the accuracy of transabdominal ultrasound (Figure 5d,f).75 Posterior placentas may be more difficult to assess.

Transvaginal ultrasound overcomes these limitations (Figure 5g–l).72,73,74,76 The probe is inserted into the vagina and therefore is closer to the region of interest.51,61 In addition, transvaginal transducers have higher frequencies and superior resolution compared to transabdominal transducers. Transvaginal ultrasound is safe and is not associated with increased bleeding.72,73,74,75,76 As such, transvaginal ultrasound should be the imaging modality of choice whenever there is suspicion of placenta previa.49,67,77

Placenta accreta spectrum

Placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) refers to abnormal implantation of the placenta into the uterine wall, where the normal plane of separation, known as Nitabuch’s layer, is absent.50,60 As a result, the placenta cannot detach from the uterine wall after delivery, leading to severe and potentially life-threatening hemorrhage.50,60,61 Fortunately, the condition can be diagnosed by ultrasound prenatally, allowing appropriate management to avoid severe maternal morbidity and mortality (Figure 6a–h; Video 3).

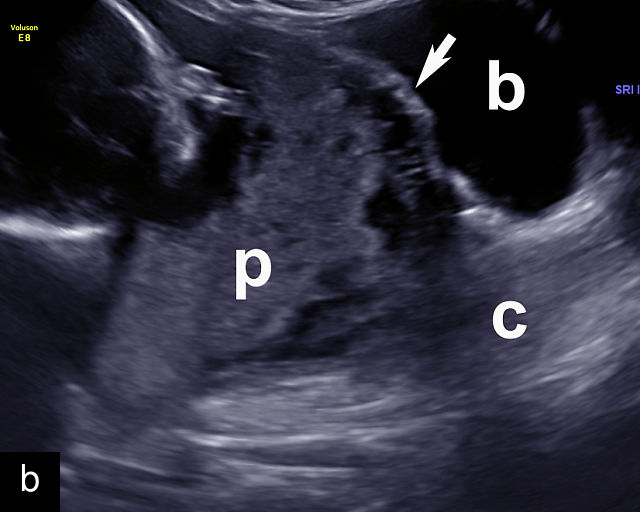

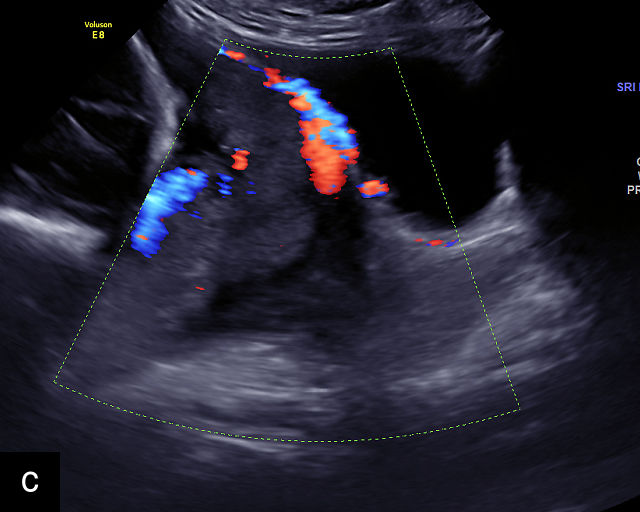

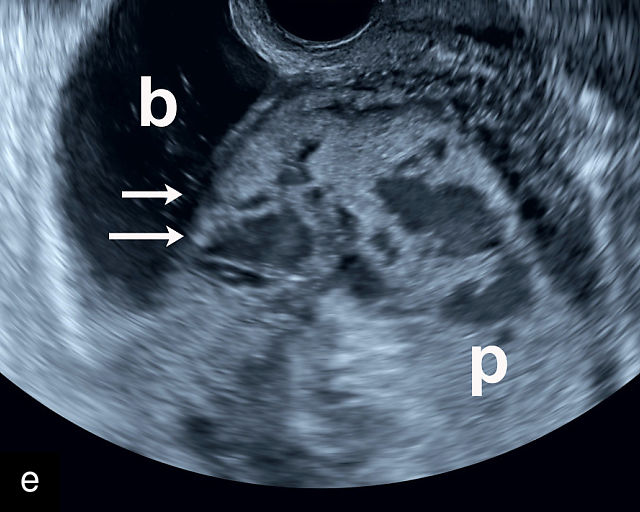

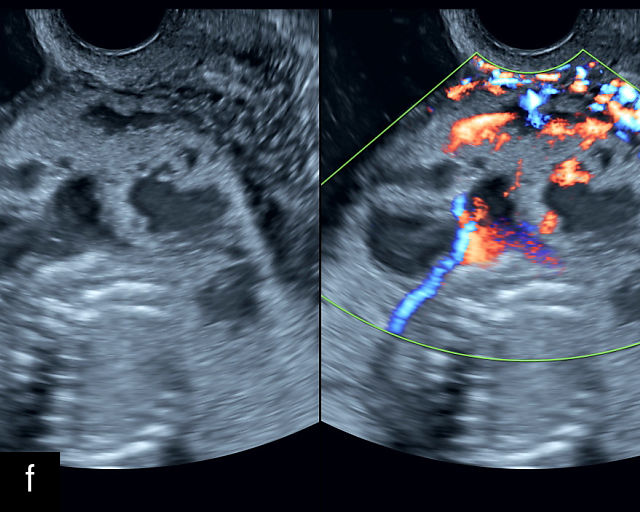

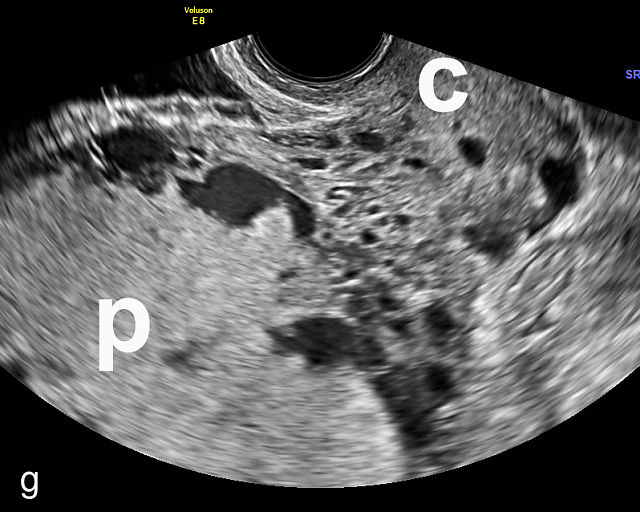

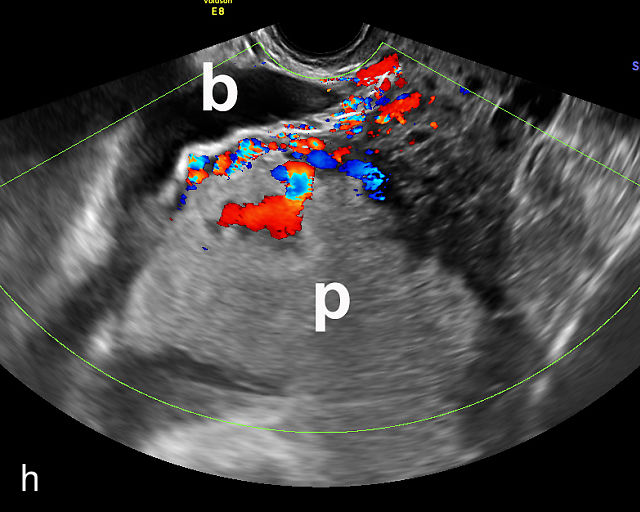

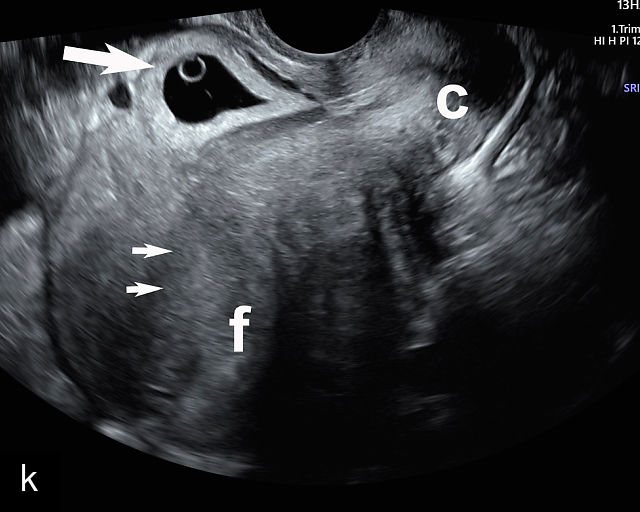

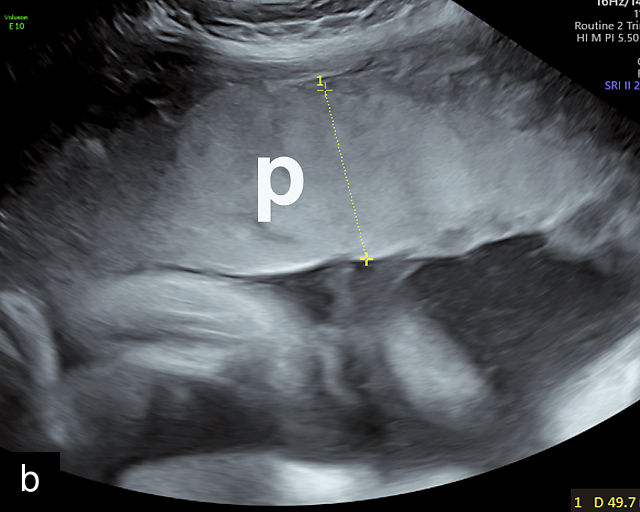

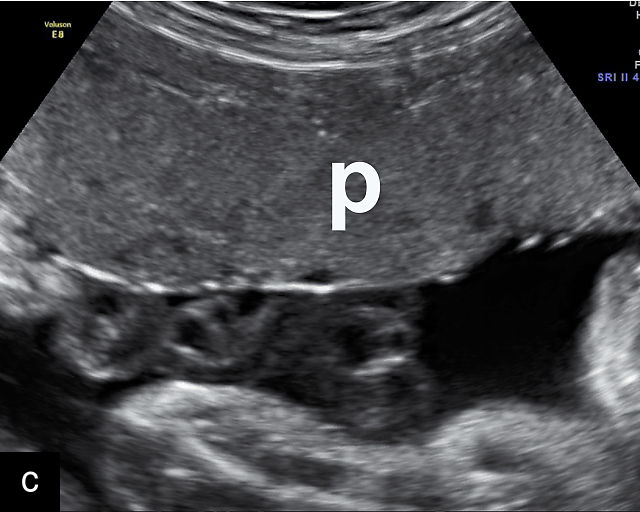

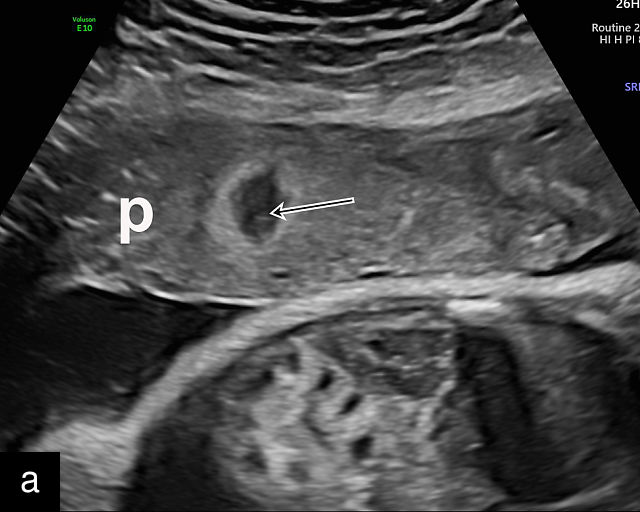

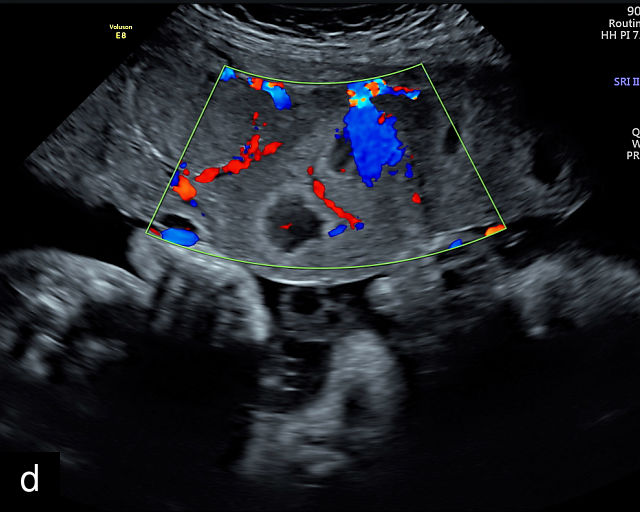

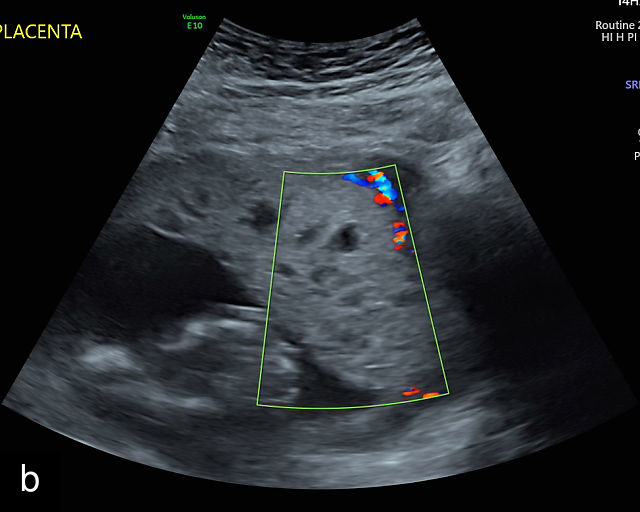

6

Placenta accreta spectrum. (a,b) Sagittal transabdominal grayscale ultrasound of the lower uterus and cervix demonstrating placenta previa accreta, with the placenta (p) containing prominent irregular hypoechoic lacunae. There is absence of the myometrium at the bladder (b) interface (arrows) c, cervix. (c) Sagittal transabdominal color Doppler ultrasound of the lower uterus and cervix demonstrating placenta previa accreta, with increased vascularity of the lower uterus and the myometrial bladder interface. (d) Transvaginal ultrasound of placenta previa accreta showing multiple lacunae involving the cervix with no clear demarcation between the placenta and the cervix. (e) Transvaginal ultrasound of placenta previa accreta showing multiple large irregular lacunae involving the cervix with no clear demarcation between the placenta (p) and the cervix. The placenta has a ‘moth-eaten’ appearance. There is loss of myometrium (arrows). (f) Transvaginal ultrasound of placenta previa accreta without and with color flow Doppler showing multiple large irregular lacunae. The placenta has a ‘moth-eaten’ appearance. There is hypervascularity of the myometrial interface. (g) Transvaginal ultrasound of placenta previa accreta showing multiple lacunae involving the cervix with no clear demarcation between the placenta and the cervix. (h) Transvaginal ultrasound of placenta previa accreta with color flow Doppler showing hypervascularity of the myometrial interface and irregularity of the bladder wall. b, bladder; p, placenta. (i) Transabdominal grayscale ultrasound of cesarean scar pregnancy. The uterine fundus (f) is empty (arrowhead). The gestational sac (arrow) is located in the lower uterus, anterior to the uterine canal, and lies above the cervix (c). b, bladder. (j) Transvaginal grayscale ultrasound image of cesarean scar pregnancy showing the empty fundus (f) and the normal cervix (c). The gestational sac lies below the fundus, above the cervix and anterior to the uterine cavity. (k) Transvaginal grayscale ultrasound image of cesarean scar pregnancy showing the empty cavity (arrowheads) of the uterine fundus (f), and the normal cervix (c). The gestational sac lies below the fundus, above the cervix and anterior to the uterine cavity (arrow).

3

Placenta accreta. Transvaginal ultrasound shows placenta previa with multiple irregular lacunae in the placenta and irregularity of the uterine wall and myometrium–bladder interface.

Historically, PAS was classified into three distinct categories: placenta accreta, where the placenta is superficially attached to the myometrium; placenta increta, where it invades deeper into the myometrium; and placenta percreta, where it penetrates through the serosal surface and may extend into adjacent structures such as the bladder, bowel or parametrium.60,61 These classifications are now grouped under the umbrella term 'placenta accreta spectrum'.

Nearly all cases of PAS occur in the presence of placenta previa and a history of one or more prior cesarean deliveries, with the risk increasing as the number of previous cesareans rises.78,79,80 All women with both these risk factors should have screening for PAS.81,82,83,84 There is strong evidence that most cases of PAS originate as first-trimester cesarean scar pregnancies, which can be identified by ultrasound early in pregnancy (Figure 6i–k).83,85,86,87,88,89 In these cases, the embryo implants within or on the scar from a prior cesarean section. On first-trimester ultrasound, this appears as a gestational sac implanted low and anterior in the uterine cavity, with an empty endometrial cavity in the fundus (Figure 6i–k).90

Early recognition of cesarean scar pregnancy and PAS is crucial, as prenatal diagnosis and appropriate delivery planning significantly impact outcomes.50,60,84 When PAS is not diagnosed before birth, it frequently results in severe maternal morbidity, including massive hemorrhage, multi-organ failure, and the need for extensive surgical intervention.61,91 It is also associated with a substantial maternal mortality rate, particularly in cases in which delivery occurs in an inadequately prepared setting without a multidisciplinary surgical team experienced in PAS management.92

The standard approach to management involves scheduled cesarean delivery before labor, followed by hysterectomy with the placenta left in situ to prevent catastrophic hemorrhage.60,61 However, an increasing number of reports describe successful conservative management strategies that allow for uterine preservation without hysterectomy.93,94

Several characteristic sonographic findings are associated with PAS.90,95,96,97 These include placental lacunae, which appear as hypoechoic, irregular spaces within the placenta with high-velocity turbulent flow on color Doppler.16,50 Other features include obliteration of the retroplacental clear space, thinning of the myometrium in the lower uterine segment, irregularity and hypervascularity of the myometrial–bladder interface, and placental bulging into the bladder (Figure 6a–h).90,96,98,99

A more detailed discussion of placenta accreta spectrum is available in another chapter in this volume (Anomalies of Placentation: Placenta Accreta Spectrum Disorders | Article | GLOWM) and will not be expanded upon further here.

Abnormal placental thickness

Thick placenta

The normal placental thickness is approximately 1 mm for each week of gestational age after 20 weeks, and it generally does not exceed 40 mm.100 However, varying definitions of placental thickness have led to inconsistent estimates of the prevalence of a thick placenta, ranging from 0.6% to 7.6%.101 The term ‘placentomegaly’ is commonly used to describe a thickened placenta, which should be measured sagitally and under the umbilical cord insertion, if this is central (Figure 7a). Thickened placentas may result from a variety of fetal, maternal or placental conditions.101,102

7

Thick placenta (p). (a) Placentomegaly in a pregnancy affected by parvovirus with severe fetal anemia. (b) Thickened placenta in a patient with syphilis. (c,d) Thickened placenta in two patients with cytomegalovirus infection. (d) Note the placental calcifications (white spots).

Fetal causes of placentomegaly include hydrops fetalis, which may be immune or non-immune, hemoglobinopathy, particularly fetal thalassemia, and fetal infection, such as cytomegalovirus (CMV), toxoplasmosis, rubella, syphilis, Zika virus and malaria (Figure 7).2,9,103 Structural abnormalities, such as sacrococcygeal teratoma and genetic conditions like Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome, have also been associated with thickened placenta.104 Maternal conditions, including pre-eclampsia, diabetes and anemia, may also contribute. In monochorionic twin pregnancies, placentomegaly may occur in the context of twin–twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS) or twin anemia–polycythemia sequence (TAPS). PAS disorders are another potential cause of placental thickening. Heterogeneous thickening, specifically, may result from placental mesenchymal dysplasia or placental hemorrhage.105,106 Laterally positioned placentas are more likely to be measured as thickened, which may reflect either challenges in measurement or compensatory hypertrophy due to impaired blood flow. Anterior placentas tend to be thinner than posterior or fundal ones.107

When a thickened placenta is detected on ultrasound, a detailed sonographic examination of both the fetus and placenta is essential, including an assessment of amniotic fluid volume.101 Tests for fetal infection may be indicated, with specific investigations tailored to the clinical context, and antibody screening should be reviewed to rule out alloimmunization. Thickened placentas are associated with an increased risk of adverse outcome, including fetal anomalies, fetal growth restriction (FGR), perinatal acidemia, fetal death and preterm delivery.104 Management should focus on addressing the underlying condition when an etiology is identified. In cases in which no specific cause is found, serial growth scans and fetal surveillance in the late third trimester are recommended to monitor for potential complications.101

Thin placenta

Polyhydramnios may lead to placental compression and a sonographically thin placenta. This may occur in the recipient twin in TTTS. The placental compression may result in uteroplacental insufficiency. A thin placenta covering the entire uterine surface may be found in placenta membranacea, also known as placenta diffusa.108 This condition is rare, estimated to occur in 1 : 20 000 pregnancies.109 It may result in bleeding in pregnancy, FGR and retained placenta. If the placenta appears unusually thin on ultrasound, a detailed anatomical survey should be performed, and consideration given to serial ultrasounds to evaluate fetal growth and wellbeing.

Placental infarcts

Placental infarcts are hypoechoic structures within the placental body with hyperechoic rims.2,9,16 (Figure 8; Video 4). The central hypoechoic region will not demonstrate any flow using sensitive Doppler techniques (Figure 8d).9,15 In addition, they do not change size or shape over time. It is these three findings (absence of flow, the hyperechoic rim and stability in size over time) that differentiate them from placental lakes.2,9 Small infarcts are found in 20% of normal pregnancies and are generally of no consequence.2,9,15 However, multiple infarcts may be found in pregnancies with pre-eclampsia and FGR, and may be associated with increased risk for abnormal umbilical artery Doppler velocimetry and adverse outcomes.2,9

8

(a–d) Placentas (p) showing infarcts (arrows). Note the hypoechoic structures with hyperechoic rims. There is no flow demonstrable with color Doppler (d).

4

(a–c) Placental infarcts. Videoclips show multiple hypoechoic placental structures with hyperechoic rims, consistent with infarcts.

Placental abruption and hemorrhagic lesions of the placenta

Placental abruption, which complicates 0.5–1% of births, refers to the premature separation of a normally implanted placenta before the delivery of the baby.110,111,112 As the placenta is the primary source of oxygen and nutrients for the fetus, this separation poses significant risks, including fetal death or asphyxia.111,112 Placental abruption is also a major cause of preterm birth.113,114,115 Risk factors for abruption include hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, smoking, cocaine use, trauma and preterm prelabor rupture of membranes.110,116

Classically, the diagnosis of placental abruption is based on clinical symptoms such as vaginal bleeding, abdominal pain, uterine tenderness, contractions and signs of fetal distress.110,111,112 When more than 50% of the placenta separates, stillbirth is often the outcome.112,114 Maternal complications can also be severe and include disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), renal failure and the need for intensive care unit (ICU) admission.110,112,115

While the diagnosis of placental abruption is generally considered clinical, ultrasound plays an important adjunctive role.111,117 Historically, the criteria for diagnosing abruption relied on symptoms; however, in some cases, ultrasound findings may precede clinical manifestations.118,119 The definitive sonographic finding of placental abruption is retroplacental hematoma.117,120 However, various hemorrhagic placental lesions may be observed in both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients, suggesting these findings exist along a continuum that culminates in the clinical presentation of abruption.110,111,112,117,120

Ultrasound findings associated with placental abruption include (Figure 9a–l):117,120,121,122,123,124 retroplacental hematoma (Figure 9a,b; Video 5c,f); subchorionic hematoma (Figure 9c–f,h,j; Video 5d,e); heterogeneous thickened placenta and intraparenchymal hematoma (Figure 9g; Video 5a); intra-amniotic hematoma (Figure 9i); and preplacental hematoma located beneath the chorionic plate (Figure 9k,l).125

9

Placental abruption and hemorrhagic lesions of the placenta (p). (a,b) Grayscale transabdominal ultrasound showing a retroplacental hematoma (arrow). (c–f) Transabdominal grayscale ultrasound image showing an anterior subchorionic hematoma (arrow). In (c) and (f), the posterior placenta is marked by 'p'. (g) Transabdominal ultrasound showing a thickened heterogeneous placenta in a patient with clinical abruption. The arrow points to the intraparenchymal hematoma. (h) Transabdominal grayscale ultrasound image showing an anterior subchorionic hematoma (arrow). Note the heterogeneous appearance with ‘layering’. (i) Large intra-amniotic hematoma (arrow). Note the ‘layering’. (j) Posterior subchorionic hematoma (arrow). The anterior placenta is marked by ‘p’. (k,l) Posterior placenta (p) with preplacental hematoma (arrow) of the chorionic plate (also known as Breus’ mole).

5

Placental abruption and hemorrhagic lesions of the placenta. (a,b) Posterior placenta containing an intraparenchymal hematoma. Note the ‘layering’ caused by organization of the clot. (c) Anterior placenta containing a retroplacental hematoma. Note the ‘layering’ caused by organization of the clot. (d,e) Anterior subchorionic hematoma. (f) Anterior placenta containing a retroplacental hematoma. Note the ‘layering’ caused by organization of the clot.

Importantly, the appearance of the hematomas may evolve over time as the clot organizes, varying from hypoechoic, when it has recently occurred to heterogeneous with layering and echogenic when it changes structure (or becomes organized) over time. Understanding this spectrum of ultrasound findings is crucial for identifying placental abruption, particularly in its earlier stages, and optimizing management to improve maternal and fetal outcomes.117,120 When these sonographic findings are encountered in the presence of a clinical diagnosis of abruption, the specificity for abruption is over 90%.123,124 Studies on ultrasound diagnosis of abruption have shown considerable variability in their sensitivity, from about 30% to 80%, with most suggesting that ultrasound has poor sensitivity for diagnosing abruption.110,126 However, these studies are limited because of the wide variety of what is considered sonographic findings diagnostic of abruption.123 Some consider only a retroplacental hematoma to be a sonographic finding consistent with abruption.117,120,127 However, when Yeo and colleagues assessed multiple ultrasound findings, listed above, in symptomatic patients, they found a sensitivity of 80%.123 Importantly, the retroplacental complex which is hypoechoic, or the presence of a localized subplacental contraction, should not be mistaken for abruption, nor should uterine fibroids.

Placental calcifications

Scattered placental calcifications can be associated with fetal infections such as toxoplasmosis, rubella, herpes, SARS-CoV-2, Zika virus and cytomegalovirus (Figure 10).128,129,130,131,132 When identified, a detailed fetal sonographic evaluation is warranted, and serologic testing for fetal infection should be considered.

10

Scattered placental calcifications in a case of congenital cytomegalovirus infection. The placenta is also thickened.

Placental cysts

Placental cysts are relatively uncommon and are most often located on the fetal surface of the placenta or along the chorionic plate.133,134,135,136,137 When identified, it is important to assess them carefully to rule out hemorrhagic lesions, as hematomas resulting from ruptured chorionic vessels can lead to fetal anemia.138,139 This distinction can typically be made sonographically: true cysts appear anechoic, whereas hematomas tend to contain echogenic fluid. Placental cysts are generally associated with favorable pregnancy outcomes; however, some case reports have noted an association with FGR.137,140 Thus, serial ultrasound evaluations are recommended to monitor for any changes in the cysts and to assess fetal growth (Figure 11; Video 6).

11

Placental cysts. (a–d) Hypoechoic cystic structures on the fetal surface of the placenta. (e) Hypoechoic cyst within the placental parenchyma.

6

Placental surface cysts.

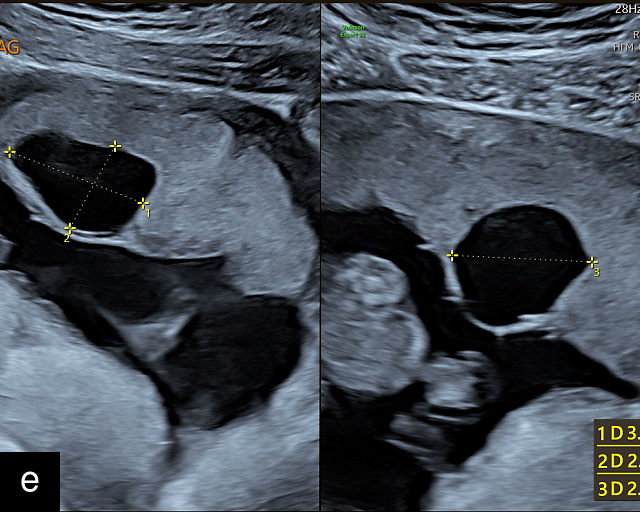

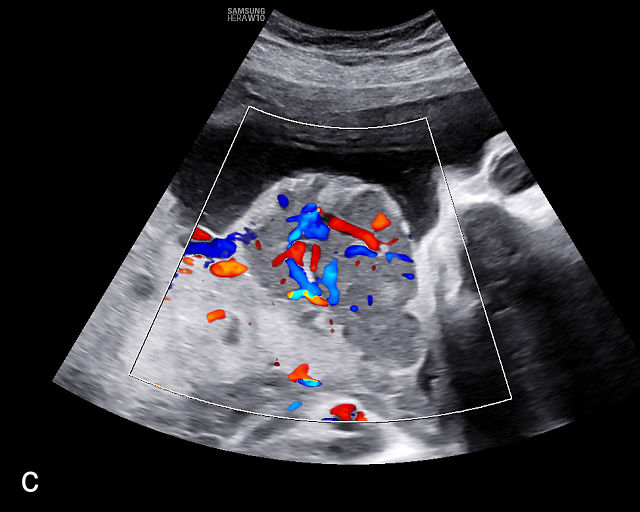

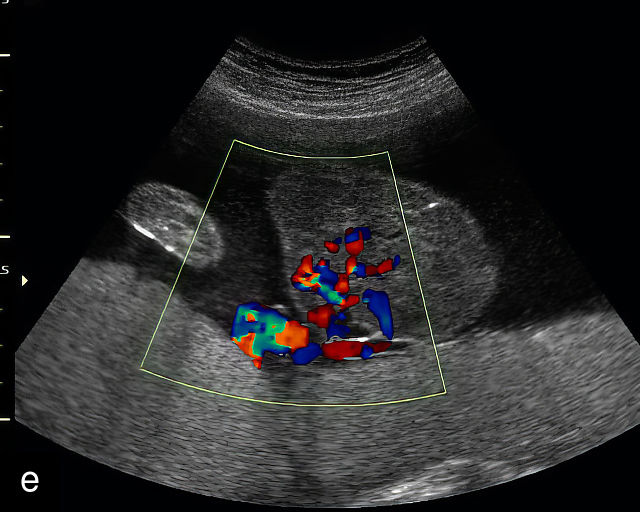

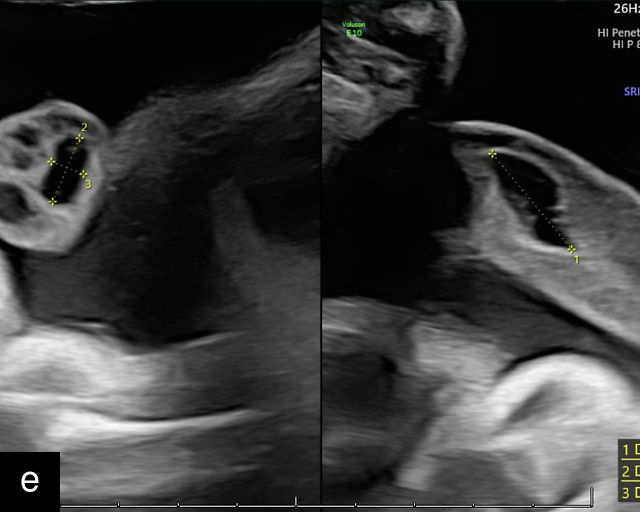

Placental chorioangiomas

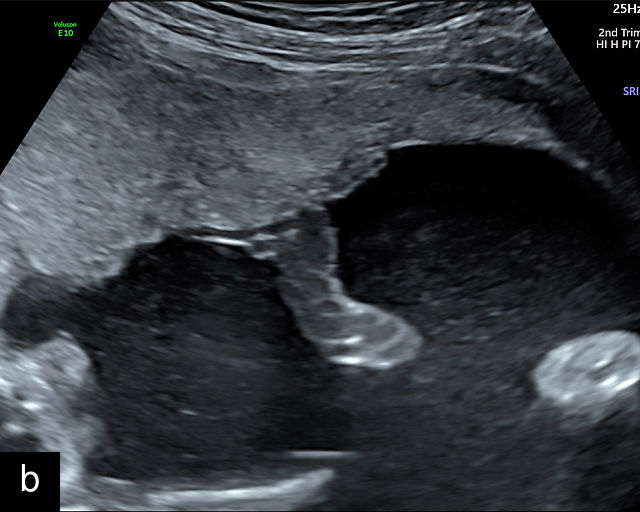

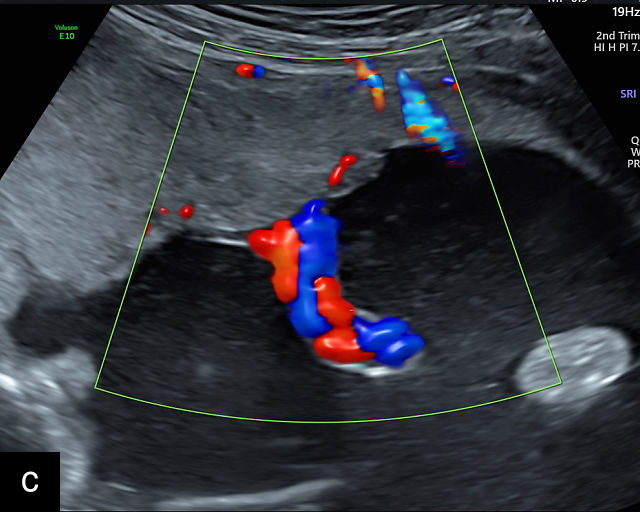

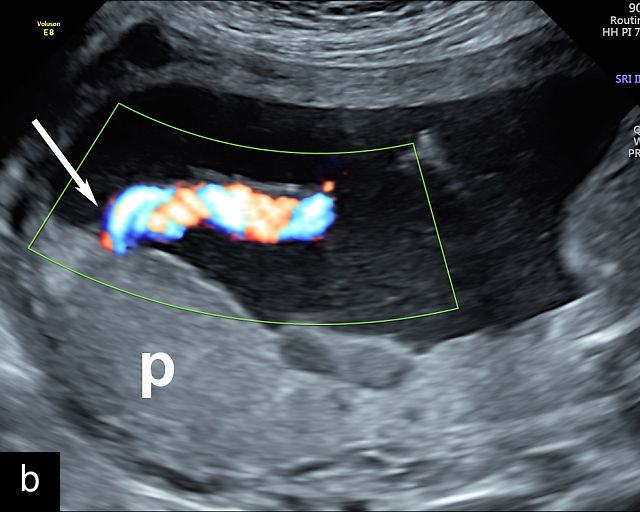

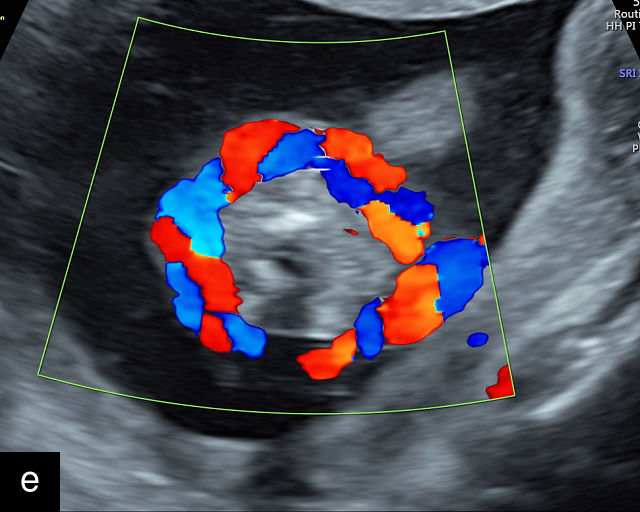

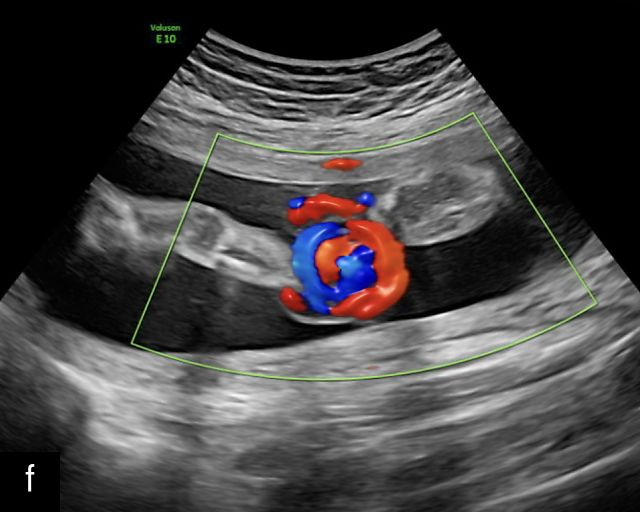

Chorioangiomas are benign tumors of the placenta, arising from chorionic tissue.141 These tumors consist of capillaries and cellular stroma in varying proportions.141,142 While clinical diagnosis of chorioangiomas is relatively uncommon, histopathological analysis reveals their presence in approximately 1% of all placentas.142 Most chorioangiomas identified on prenatal ultrasound are incidental findings during routine examination and are typically those that are larger in size.9 Consequently, the prevalence of chorioangiomas detected sonographically is significantly lower than the prevalence observed in pathological examinations of placentas. More rarely, chorioangiomas may be detected during ultrasound evaluation for polyhydramnios or FGR.143 Large chorioangiomas (greater than 4 cm in diameter) are thought to occur in approximately 1 : 3500–1 : 9000 pregnancies (0.01–0.03%).141 These larger chorioangiomas may be associated with significant complications, including polyhydramnios, fetal hydrops, fetal anemia, FGR and even fetal death.9,141,143,144,145 A systematic review reported a fetal death rate of 8.2% in cases of prenatally diagnosed chorioangioma in which no intervention was performed.145 Additionally, preterm birth before 37 weeks occurred in 34.1% of these pregnancies (95% CI, 21.1–48.3%). The study also found that 24.0% of infants (95% CI, 13.5–36.5%) were born small-for-gestational age.145 The most important predictor of outcomes was the size of the tumor.145

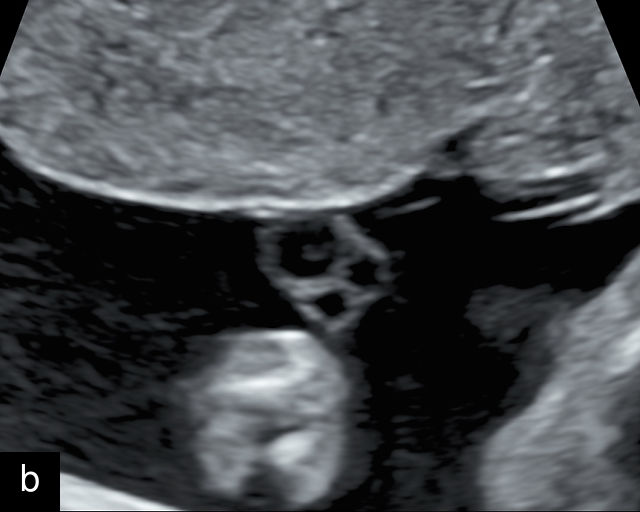

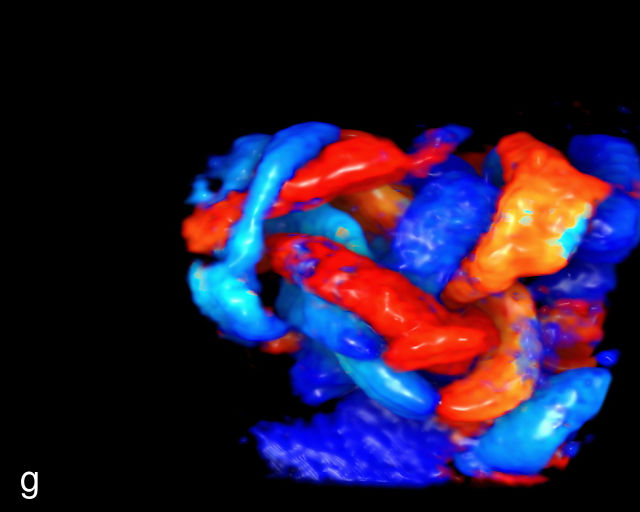

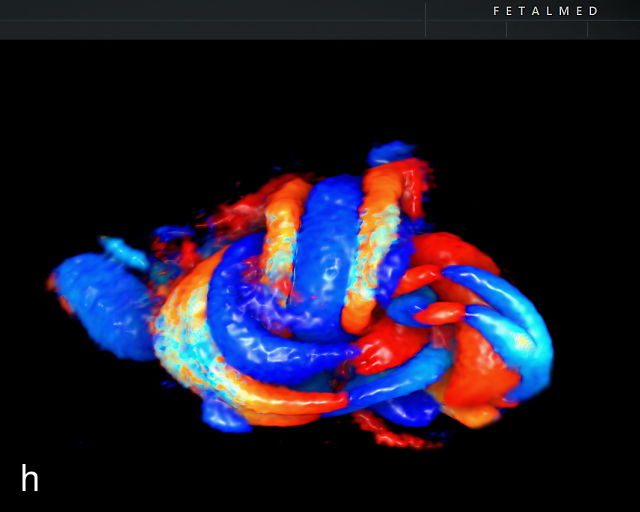

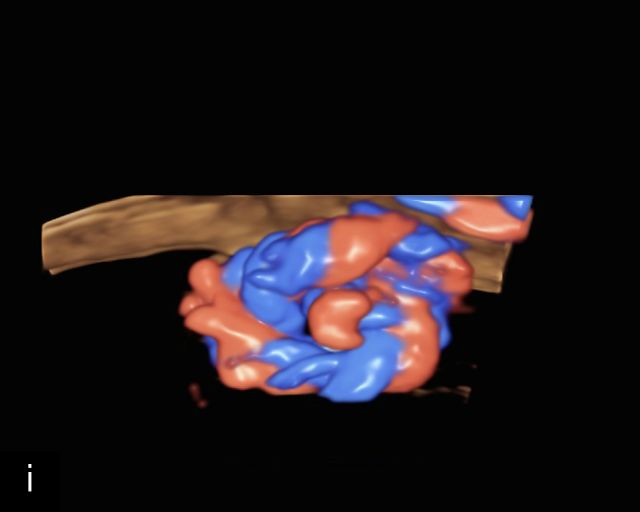

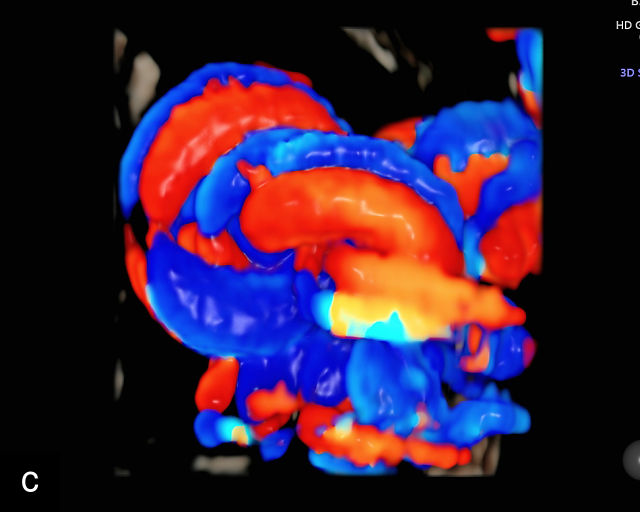

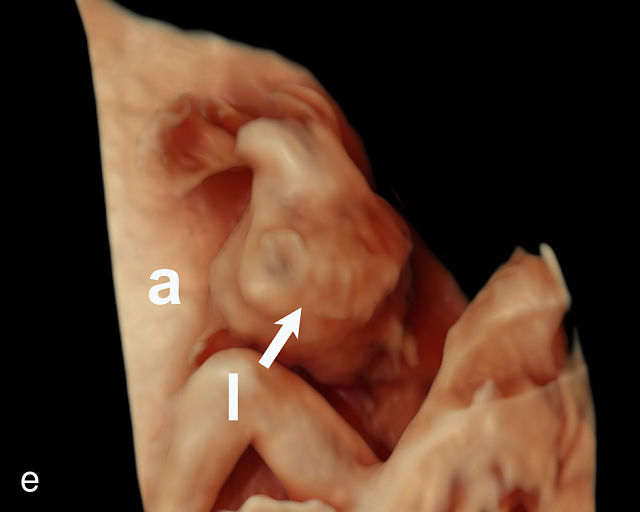

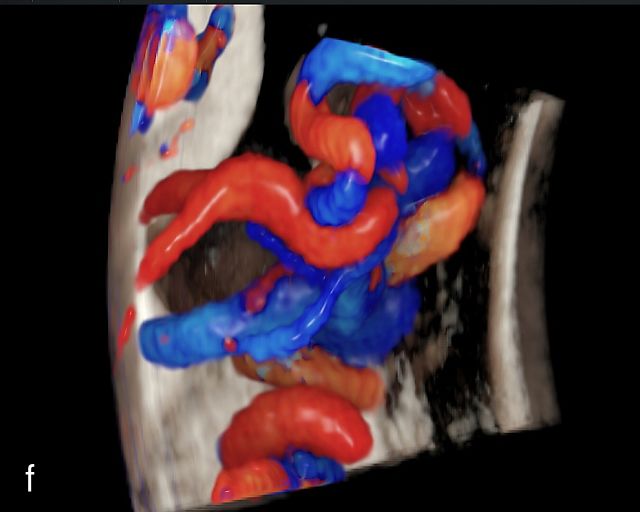

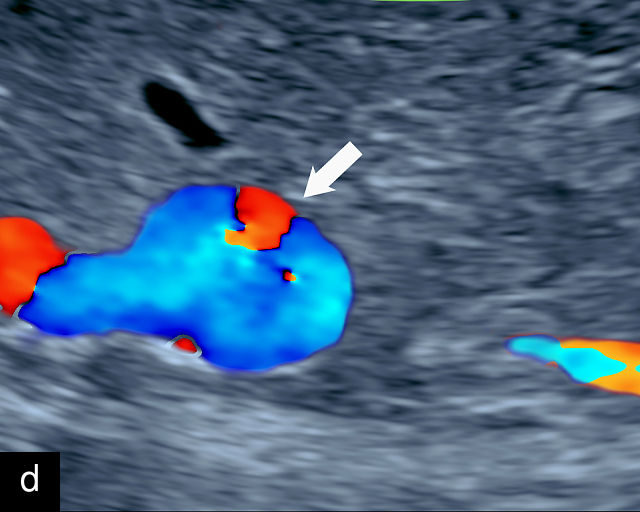

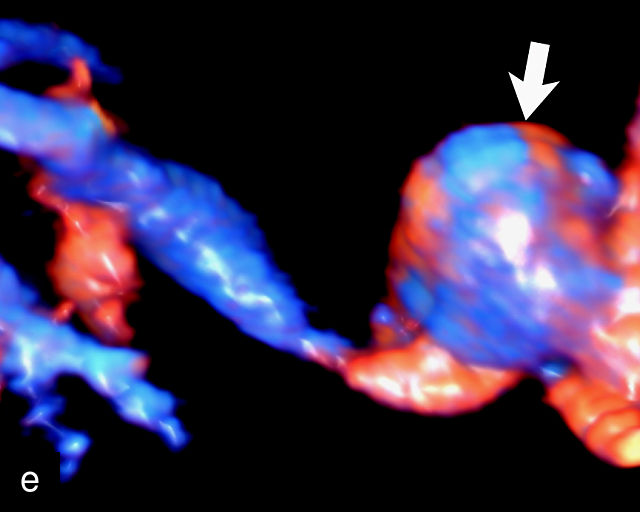

The typical sonographic appearance of a chorioangioma on grayscale ultrasound is a well-circumscribed mass arising from the fetal surface of the placenta, protruding into the amniotic cavity, and distinctly separate from the placenta (Figure 12; Video 7). These tumors are most commonly located near the umbilical cord insertion site on the placenta. Sonographically, they may appear hypoechoic or hyperechoic and are often heterogeneous, with possible calcifications, hemorrhage or infarction visible within the mass.9 The appearance of these masses may change over time.141 Color flow Doppler imaging typically reveals vascularity within the tumor, showing low-resistance vessels and arteriovenous shunts (Figure 12c–e; Video 7).9 These shunts are believed to contribute to fetal complications such as high-output cardiac failure, anemia and hydrops.141 Three-dimensional ultrasound may be helpful in assessment of the mass.146 Importantly, the differential diagnosis includes placental hemorrhage, and color flow Doppler is essential to assist in making the diagnosis.

12

Grayscale (a,b), color Doppler (c,e) and power Doppler (d) images of chorioangiomas, showing heterogeneous masses protruding from the placental surface.

7

(a–c) Color flow and power Doppler imaging of placental chorioangiomas.

When a chorioangioma is identified on prenatal ultrasound, close fetal surveillance is essential. Initial monitoring includes weekly ultrasound examinations to assess amniotic fluid volume and fetal cardiac function, as polyhydramnios and hydrops can develop rapidly. Polyhydramnios is the most common complication of chorioangioma, complicating between 14% and 28% of cases, and when severe, may lead to maternal discomfort, respiratory embarrassment and preterm labor.141,143,147,148 Fetal growth should be evaluated every 4 weeks. Maternal mirror syndrome, with severe pre-eclampsia has also been described.149,150

Management of complications related to chorioangioma may include interventions such as amnioreduction to manage severe polyhydramnios.149,151 More recently, a variety of fetal surgical procedures have been developed to treat these tumors, with varying degrees of success. Additional interventions include intrauterine fetal transfusion to correct anemia and various fetoscopic techniques to occlude tumor vessels, such as embolization with injection of vascular plugs, and radiofrequency or laser ablation of the feeding vessels.143,144,152,153,154,155,156,157

Rare placental tumors

Rarer placental tumors include teratomas and choriocarcinomas.158 Metastatic malignancies have rarely been found in the placenta, though they should be considered in the differential diagnosis when placental masses are found on ultrasound.

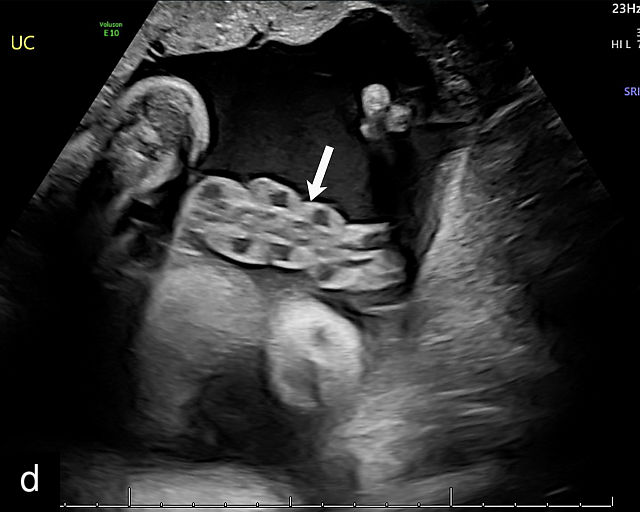

Circumvallate placenta

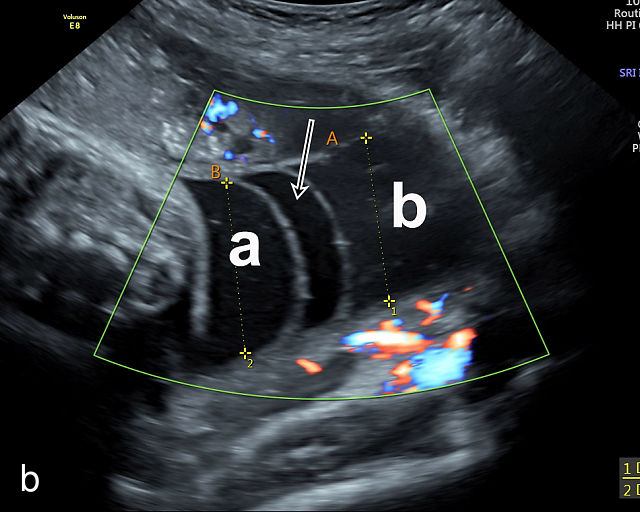

A circumvallate placenta is one in which the chorionic plate (the fetal surface of the placenta) is smaller than the basal plate, resulting in placental tissue extending beyond the margins of the membrane insertion.9 This creates rolled edges with a cuplike appearance. Rather than inserting at the edges of the placenta, the membranes insert into the fetal surface. In a review of 16 042 placental pathology reports collected over 13 years, Stuijt et al. found that circumvallate placentas were present in 2.2% of cases.159 Circumvallate placentas have been associated with an increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes, including FGR, placental abruption, preterm birth and fetal demise.160,161

Sonographically, a circumvallate placenta appears as a placenta with raised, rolled edges, which can be identified on grayscale ultrasound (Figure 13). Additionally, a placental shelf or band may be observed at the placental margin. The differential diagnosis includes amniotic bands, uterine synechiae and uterine septa. However, achieving an accurate prenatal diagnosis can be challenging. An early study by Harris et al. found a poor correlation between the sonographic diagnosis of circumvallate placenta and confirmation on placental examination after delivery.162 In that study, placental sonograms reviewed by expert sonologists showed that 17 of 49 normal placentas were incorrectly diagnosed as probably or definitely circumvallate by one or more observers. Conversely, in a study of 10 patients in which prenatal ultrasound had revealed raised rolled placental edges thought to represent circumvallate placenta, the diagnosis was confirmed on gross placental examination in eight cases.163 This high false-positive rate poses a significant challenge in prenatal ultrasound diagnosis and impacts the interpretation of reported outcomes. The difficulty in achieving an accurate diagnosis likely contributes to the wide range of reported prevalence of circumvallate placenta.

13

(a–e) Grayscale images of circumvallate placentas showing the rolled edges of the placentas.

Recent evidence provides additional insight into the clinical significance of this condition. A retrospective cohort study by Herrera et al. examined 179 patients with a prenatal diagnosis of circumvallate placenta at an average of 19.8 weeks.164 The study found no correlation between a circumvallate placenta and adverse pregnancy outcome. These authors suggested that no additional surveillance was necessary when a circumvallate placenta is suspected on prenatal ultrasound. This difference in reported outcomes may reflect the false-positive diagnoses of circumvallate placenta in sonographic studies.

When findings consistent with a circumvallate placenta are observed on prenatal ultrasound, efforts should focus on achieving an accurate diagnosis. The use of three-dimensional ultrasound may improve diagnostic accuracy.9,165,166 If a circumvallate placenta is confirmed or strongly suspected, serial growth scans and consideration of antepartum fetal surveillance in the late third trimester are prudent to monitor for potential complications.

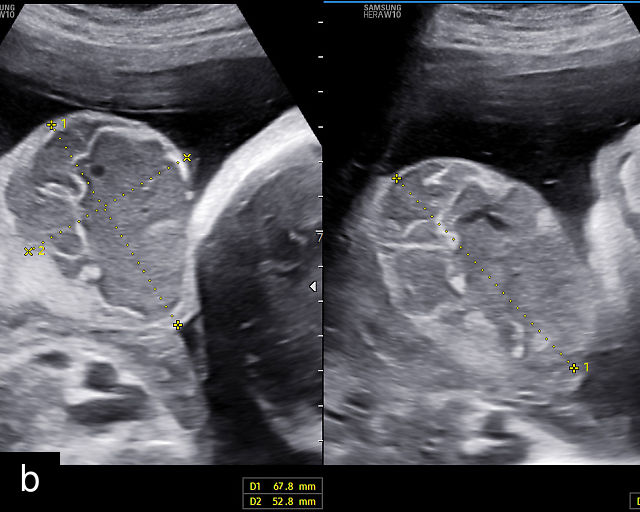

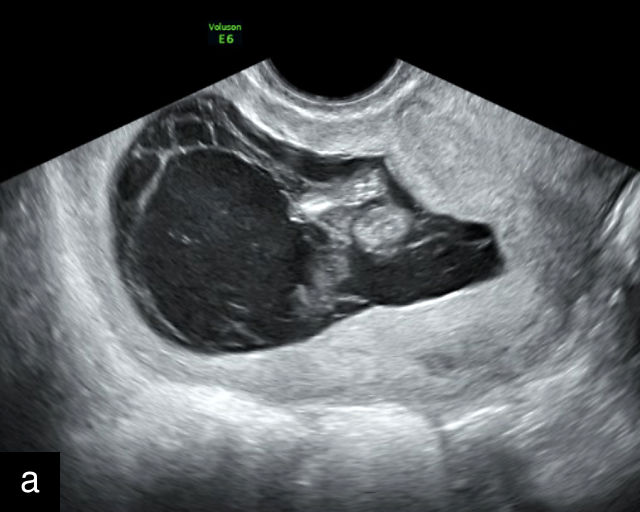

Placental mesenchymal dysplasia

Placental mesenchymal dysplasia (PMD) was first described by Moscoso et al. in 1991.167 It is an uncommon placental vascular abnormality characterized by mesenchymal stem villous hyperplasia, edema and cystic dilation.9,105,168 PMD complicates approximately 1 in 500 pregnancies (0.2%) and is often associated with placental mosaicism.9 There is a 3.6 : 1 female: male preponderance. Maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels may also be markedly elevated in these pregnancies.169 Despite its clinical significance, PMD is underreported, and many sonographers, obstetricians and pathologists are unfamiliar with the condition, often confusing it with a hydatidiform mole.106,153,170,171,172

PMD is strongly associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes, including pre-eclampsia, FGR and fetal demise.106,173 It has also been found in association with Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome and various congenital anomalies, including skeletal dysplasias and CHARGE syndrome.106,174,175,176 A systematic review by Nayeri et al. reported that only 9% of pregnancies with PMD resulted in a normal outcome for the baby106.

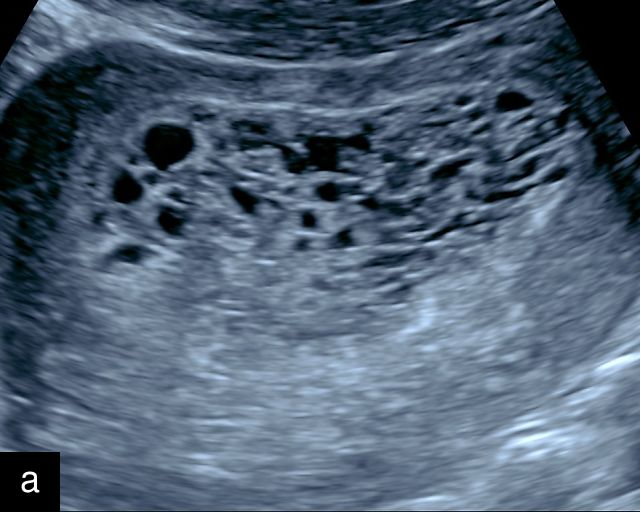

On ultrasound, PMD appears as a thickened placenta with multiple small cysts of varying size, creating a 'snowstorm' appearance that closely resembles a hydatidiform molar pregnancy (Figure 14; Video 8).9,105,106,169,172 Differentiating PMD from a molar pregnancy can be challenging, particularly in twin pregnancies in which a normal twin coexists with a cotwin that has an enlarged, cystic placenta.169 In complete molar pregnancy, the uterus is entirely filled with cystic tissue, showing a snowstorm appearance without identifiable fetal structures. Partial molar pregnancies, on the other hand, typically feature an enlarged cystic placenta coexisting with an abnormal fetus.105

14

(a–e) Grayscale ultrasound of placental mesenchymal dysplasia showing thickened placentas with multiple round cysts of varying size.

8

(a–c) Ultrasound imaging of placental mesenchymal dysplasia.

Several features can help distinguish PMD from molar pregnancy. In molar pregnancy, human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) levels are typically dramatically elevated, whereas in PMD, hCG levels are usually normal or only mildly elevated.106,177 Elevated maternal AFP levels are more characteristic of PMD. Doppler imaging in molar pregnancies shows hypervascularity with low-resistance flow, a consequence of trophoblastic proliferation, while vascularity in PMD is generally normal or only mildly increased, with normal resistance. Low-risk results from non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) using cell-free DNA and the presence of a normal-appearing fetus further support a diagnosis of PMD and make triploidy or partial molar pregnancy unlikely.

Management of these two conditions differs significantly. Molar pregnancies require uterine evacuation and follow-up with serial hCG measurements to monitor for persistent trophoblastic disease. In contrast, PMD may result in a viable pregnancy but carries greatly increased risk of FGR and fetal demise, necessitating close monitoring and intervention when indicated.106

Molar pregnancy

Molar pregnancy, or hydatidiform mole, is a form of gestational trophoblastic disease characterized by abnormal proliferation of trophoblastic tissue and hydropic degeneration of chorionic villi.178,179,180 It is broadly classified into complete and partial types. A complete mole arises from fertilization of an enucleate ovum by one or two sperm, resulting in a diploid karyotype, typically 46,XX, composed entirely of paternal genetic material and lacking an embryo or fetus. A partial mole, by contrast, results from fertilization of a normal ovum by two sperm, leading to a triploid karyotype, most commonly 69,XXY or 69,XXX, and often includes an abnormal fetus.179 Clinically, patients may present with vaginal bleeding, excessive uterine size for gestational age, hyperemesis gravidarum and significantly elevated beta-hCG levels.178 Ultrasound is the diagnostic modality of choice: a complete mole demonstrates a heterogeneous intrauterine mass with numerous anechoic cystic spaces, often described as a ‘snowstorm’ or ‘cluster of grapes’, with no identifiable embryo or amniotic sac (Figure 15).178,181 Color Doppler typically reveals a hypervascular pattern with high-velocity, low-resistance flow due to abnormal trophoblastic vasculature. In partial moles, sonography may reveal a thickened, cystic placenta alongside a growth-restricted fetus, often with structural anomalies such as hydrocephalus, cardiac defects or syndactyly. Doppler evaluation may show signs of placental insufficiency, including absent or reversed end-diastolic flow in the umbilical artery.182 In addition, in molar pregnancies, there may be bilateral enlargement of both ovaries with multiple theca lutein cysts.183 Accurate and timely diagnosis is essential to prevent complications such as persistent gestational trophoblastic neoplasia and to guide appropriate clinical management.181,184

15

Molar pregnancy. (a) Transvaginal grayscale ultrasound at 8 weeks’ gestation demonstrating features of a complete molar pregnancy. The uterus is enlarged and filled with a heterogeneous echogenic mass containing multiple small anechoic cystic spaces, producing a characteristic 'snowstorm' or 'cluster-of-grapes' appearance. No identifiable embryo or normal gestational sac is seen. The myometrium appears normal in echotexture, and there is no evidence of adnexal mass or free fluid. (b) Transabdominal grayscale ultrasound at 9 weeks’ gestation demonstrating a dichorionic twin pregnancy with a complete mole co-existing with a normal appearing embryo in a separate sac. One sac is filled with a heterogeneous echogenic mass containing multiple small anechoic cystic spaces, producing a characteristic 'snowstorm' or 'cluster-of-grapes' appearance.

UMBILICAL CORD

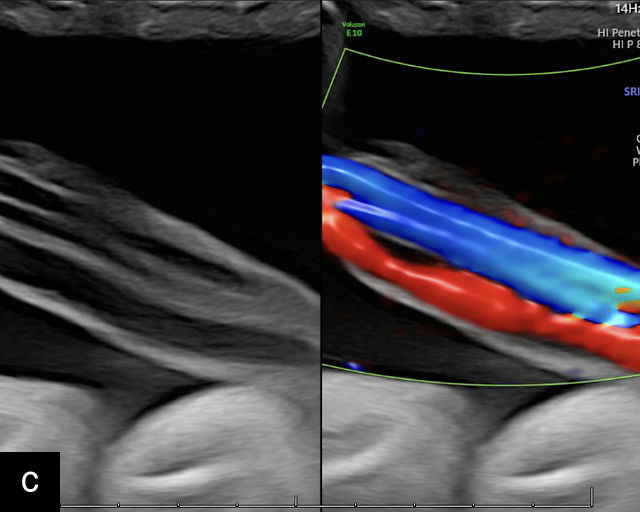

Normal anatomy, development and ultrasound appearance

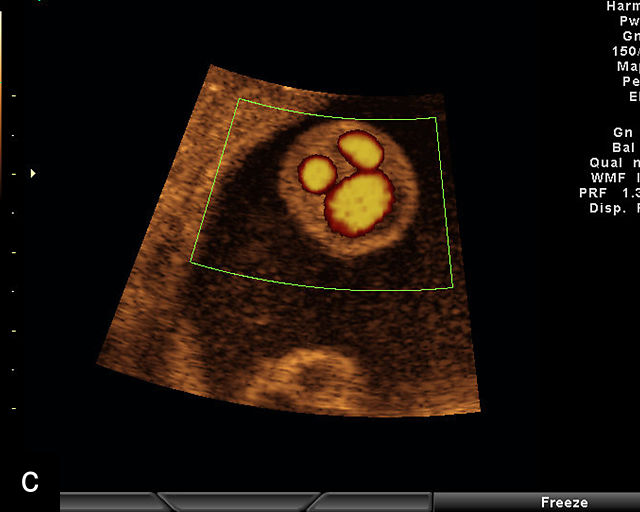

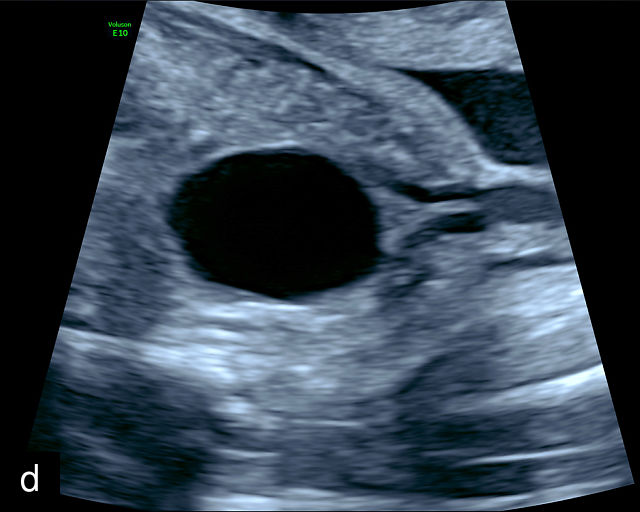

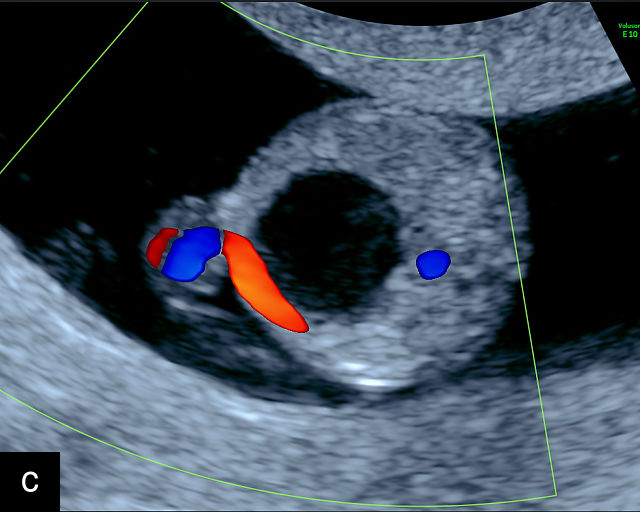

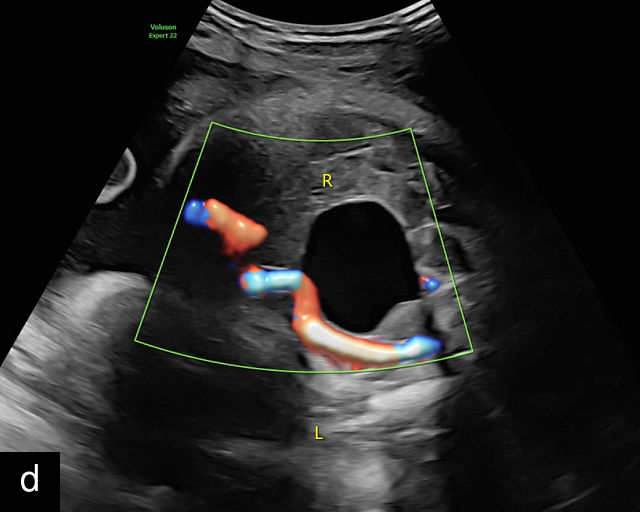

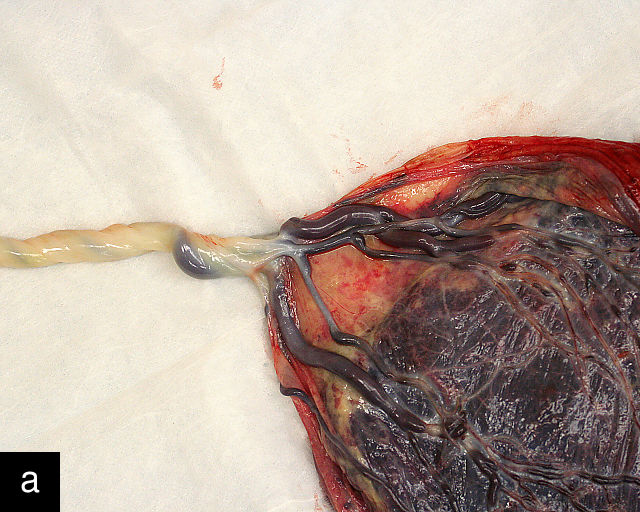

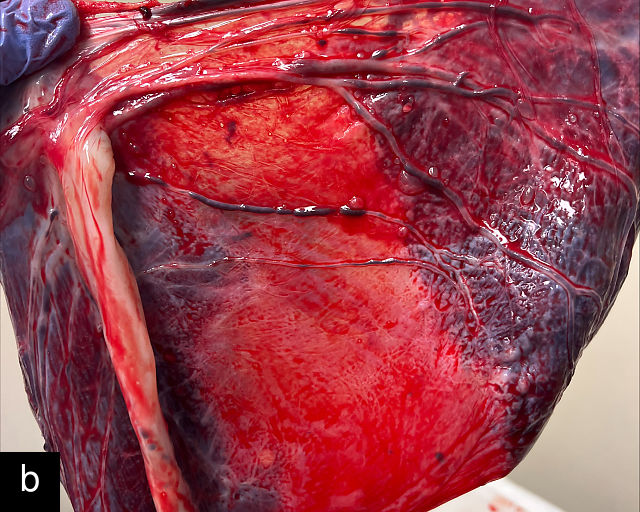

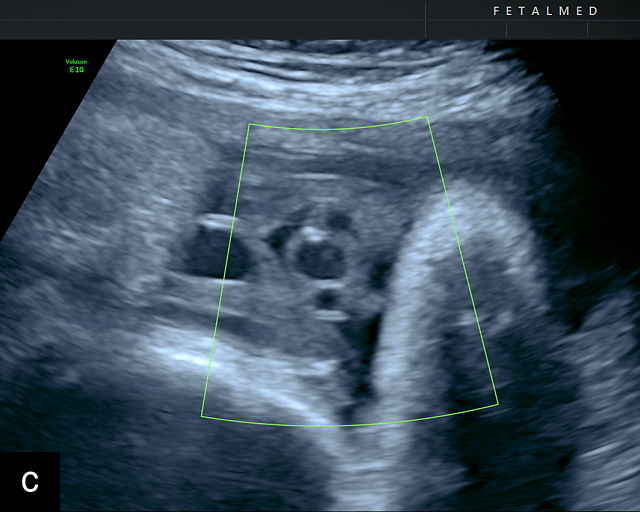

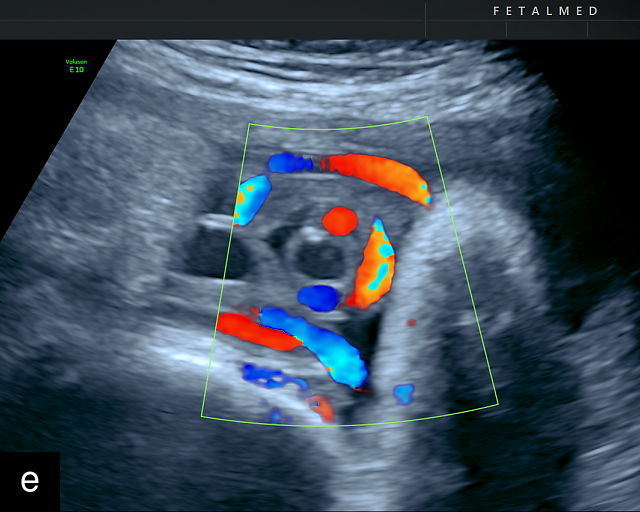

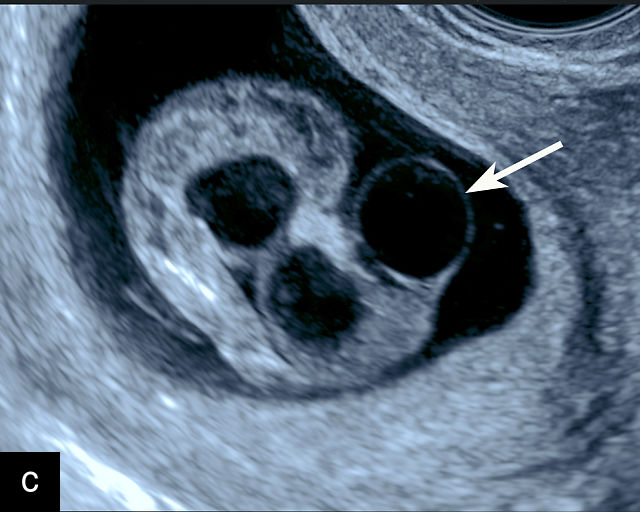

The umbilical cord serves as the lifeline connecting the fetus to the placenta. It arises from the midportion of the fetal abdomen and typically inserts into the center of the placenta (Figure 16). The average length of the umbilical cord is approximately 55 cm (22 inches).185 It contains three vessels: two arteries, which originate from the fetal left and right internal iliac arteries, and one vein, collectively referred to as a three-vessel cord.

16

Normal appearance of the umbilical cord with two umbilical arteries and a single vein. (a–c) Cross-section of the umbilical cord on grayscale (a,b) and power Doppler (c) ultrasound. In the normal cord, three vessels are visible: a larger umbilical vein and two smaller umbilical arteries. This characteristic appearance is often referred to as the 'Mickey Mouse' sign, the larger circle (umbilical vein) representing Mickey’s face while the smaller circles (arteries) form his ears. (d–g) Grayscale (d) and color Doppler (e–g) images of transverse section of the lower fetal abdomen showing the two umbilical arteries diverging around the fetal bladder. (h) Longitudinal ultrasound view with color Doppler of a normal umbilical cord showing three vessels present in each coil: two arteries with flow in one direction and a single vein with flow in the opposite direction.

The umbilical vein carries oxygenated blood from the placenta to the fetus, while the two umbilical arteries return deoxygenated blood and waste products from the fetus to the placenta for exchange with the maternal circulation. These vessels are surrounded and protected by Wharton’s jelly, a specialized connective tissue derived from the extraembryonic mesoblast, which cushions the vessels and prevents compression. As the umbilical cord approaches its placental insertion, the two arteries form Hyrtl’s anastomosis, a connection that helps equalize blood flow between the arteries.

At a minimum, the mid-trimester ultrasound should include identification and documentation of the umbilical cord's fetal and placental insertions, as well as the number of cord vessels.66,186,187 In a transverse grayscale section of the cord, the two umbilical arteries can be visualized alongside the larger, thinner-walled umbilical vein, creating a characteristic ‘Mickey Mouse’ appearance (Figure 16a–c). Additionally, in a transverse section of the lower fetal abdomen, the umbilical arteries are seen encircling the fetal bladder. This can be seen on grayscale ultrasound and confirmed with color flow Doppler (Figure 16d–g).

A normal umbilical cord is helical, with an average of 2.1 coils per 10 cm of cord length.188,189 The majority of umbilical cords exhibit a leftward (counterclockwise) twist, with a left-to-right twist ratio of approximately 7 : 1, making the rightward (clockwise) twist significantly less common.185,190,191 This twisting structure is believed to provide additional protection against compression and kinking during pregnancy.192

Thus, several mechanisms work together to protect the fetal vessels from occlusion. These include the cushioning effect of Wharton’s jelly, the helical twisting of the cord, normal length of the cord (which prevents excessive tension, twisting, knots or compression), Hyrtl’s anastomosis (which equalizes blood flow between the arteries) and the surrounding amniotic fluid, which provides additional protection and buoyancy. Aberrations in any of these protective factors may compromise the cord and increase the risk of fetal death or other adverse outcomes.192,193

After birth, the umbilical arteries undergo obliteration and eventually form the medial umbilical ligaments within the abdominal wall.

Abnormal umbilical cord findings

Single umbilical artery

Assessment of the number of vessels in the umbilical cord is a component of routine obstetric ultrasound.66 As mentioned above, the umbilical cord typically contains two arteries and one vein, however, a single umbilical artery (SUA) is observed in approximately 1% of pregnancies.4,194,195,196 Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain the etiology of SUA: primary agenesis of one umbilical artery, obliteration of a previously formed artery or fusion of two separate arteries. When there is a SUA, there is a compensatory increased diameter of the single artery.197

SUA is one of the most common umbilical cord abnormalities detected on prenatal ultrasound.191,198 When a SUA is present, only a single vessel is seen along one side of the bladder (Figure 17a–d), compared with the two vessels seen with a normal cord (Figure 16e–g). In a cross-section of the cord with SUA, only two vessels, one artery and one vein, are visible (Figure 17e), and the Mickey Mouse sign (Figure 16a–c) is no longer present. In a longitudinal view of the cord, a SUA is identified by the presence of only two vessels within the helix, with the single artery being almost equal in size to the vein (Figure 17f–i). Fusion of the umbilical arteries has also been noted, such that a fetus may have a single umbilical artery and two separate umbilical arteries at different points along the cord.199,200

17

Single umbilical artery (SUA). (a–d) Transverse section of lower fetal abdomen at the level of the fetal bladder. Only a single vessel is seen coursing around one side of the bladder, compared with two vessels on each side of the bladder in the normal three-vessel cord. (e) Cross section through the umbilical cord showing only two circles, representing two vessels: a single umbilical artery and a vein. Compare with the three-vessel Mickey Mouse sign in Figure 16a–c. (f–h) Longitudinal ultrasound views with color flow Doppler of an umbilical cord with a SUA, showing two vessels with flow in opposite directions. This contrasts with a normal umbilical cord, in which three vessels are present in each coil (Figure 16h). In Figure 17h, the cord is also hypercoiled. (i) Grayscale and 3D power Doppler ultrasound images of a SUA and the umbilical cord after delivery.

When SUA is identified on obstetric ultrasound, a detailed fetal anatomical survey is recommended.201 The prognosis of SUA depends on whether it is an isolated finding or associated with other fetal anomalies. SUA has been linked to a range of genetic and structural abnormalities, particularly when additional anomalies are present.201 The most commonly associated abnormalities involve the cardiovascular and renal systems.202 SUA is also associated with trisomies 21, 18 and 13 when multiple anomalies coexist. As such, screening results should be carefully reviewed. If multiple anomalies are detected, invasive testing such as amniocentesis should be offered. Conversely, if SUA is an isolated finding and aneuploidy screening produces a low-risk result, no further evaluation for aneuploidy is recommended.201 A detailed cardiac assessment, or fetal echocardiography, should be performed, although studies suggest that a normal detailed cardiac examination typically obviates the need for additional echocardiographic evaluation.203,204,205

SUA has also been associated with FGR, and there is conflicting evidence regarding an increased risk of stillbirth.201,206,207 Therefore, the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine recommends a third-trimester growth scan and consideration of antepartum fetal surveillance beginning at approximately 36 weeks.201 However, such a monitoring protocol is not universally recommended, especially if the fetal growth is normal.

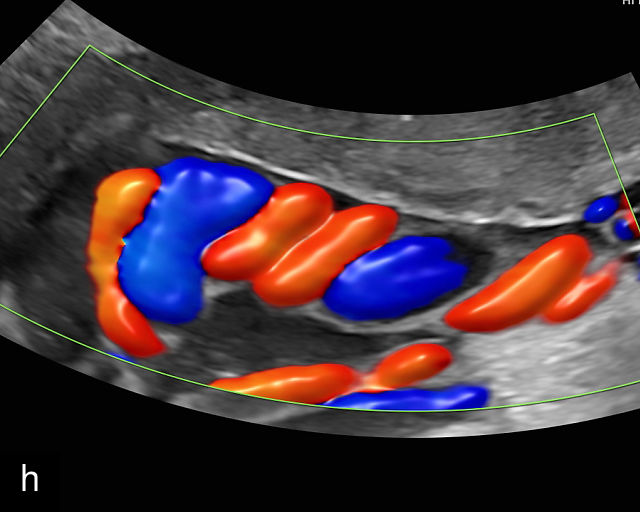

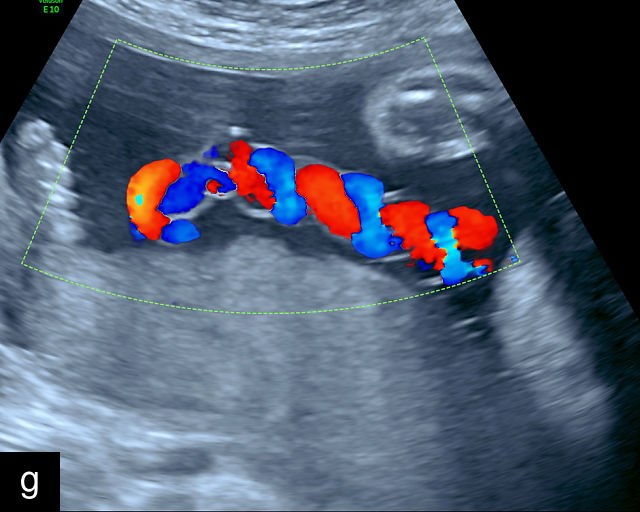

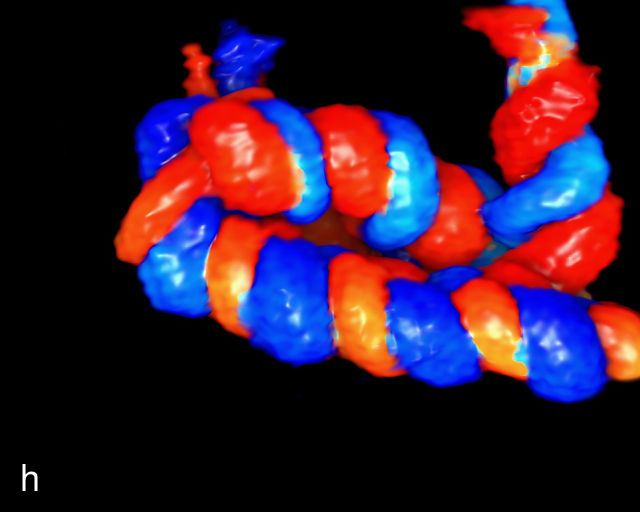

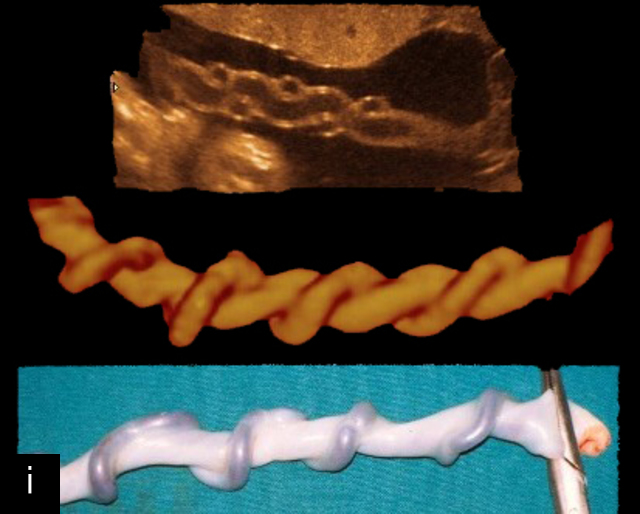

Abnormal cord coiling

The umbilical cord coiling index (UCI) is defined as the number of complete vascular coils per cm of cord, with a normal UCI averaging around 0.2.185,191 A hypocoiled cord is typically defined as having an UCI of less than 0.2, or below the 10th percentile, with approximately one coil per 10 cm of cord (Figure 18a–c). In contrast, a hypercoiled cord has an UCI greater than 0.3, or above the 90th percentile (Figure 18d; Video 9). It is estimated that hypocoiling of the cord occurs in between 4% and 15% of pregnancies.185,191

18

Umbilical cord hypocoiling and hypercoiling. (a) Grayscale ultrasound image of hypocoiled cord. (b) Color flow Doppler image of hypocoiled cord. (c) Grayscale and color flow Doppler image of hypocoiled cord. (d) Grayscale image of hypercoiled cord.

9

Imaging of umbilical cord hypercoiling using grayscale (a–c) and color Doppler (b) ultrasound.

Several factors influence cord coiling, including cord length and fetal movement.191,208 Coiling tends to increase with gestational age and serves as a protective mechanism, shielding the fetal vessels from compression. Excessive coiling may obstruct blood flow, while hypocoiling may increase the risk of vessel compression and adverse perinatal outcome.209 Hypocoiling has also been associated with conditions characterized by reduced fetal movement.

While sonographic assessment of cord coiling is feasible, the sensitivity and specificity of this finding in isolation are limited. As a result, there are no current recommendations for routine evaluation of the UCI during obstetric ultrasound. This limitation is further compounded by the fact that most UCI reference values have been derived from postnatal examination of the cord rather than by prenatal imaging. Most adverse outcomes associated with abnormal umbilical cord coiling have been reported based on pathological examination of the placenta and cord following stillbirths or other adverse events, rather than on the prenatal ultrasound detection of abnormal cord coiling.6

Nonetheless, efforts have been made to assess coiling prenatally.208 Predanic et al. reported a correlation between second-trimester ultrasound measurements of cord coiling and findings at birth but noted that prenatal ultrasound was less accurate in identifying hypocoiled or hypercoiled patterns.188,210,211 In contrast, Ma’ayeh and colleagues, in a prospective study of 72 patients, found that second-trimester sonographic assessment of the UCI did not reliably predict coiling at birth or correlate with perinatal outcomes.212 Therefore, routine assessment of umbilical cord coiling is not recommended. However, if a cord appears markedly hypocoiled or hypercoiled during a standard ultrasound examination, closer surveillance with serial ultrasounds should be considered.

Abnormal cord length

A long umbilical cord is defined as one measuring above the 90th percentile for gestational age, while a short cord falls below the 5th percentile.191,213,214 Long cords (>80 cm at term) are associated with an increased risk of complications, including nuchal cords, cord entanglement, true knots and cord prolapse, as well as fetal demise.215,216 Excessive fetal movements are thought to contribute to the development of longer cords. However, it remains unclear whether these complications are primarily a result of the cord’s length or the excessive fetal movements themselves. The risk of these complications rises with increasing cord length, and there is some evidence suggesting that longer cords may be linked to FGR.217 Remarkably, cords as long as 300 cm have been documented, although measuring cord length remains challenging and is not a routine component of sonographic assessment.

In contrast, excessively short or absent umbilical cords are frequently associated with fetal anomalies, most notably limb–body wall complex (body–stalk anomaly) and ectopia cordis. Short cords, defined as less than 35–40 cm in length, are also linked to conditions such as fetal hypokinesia/akinesia sequence (Pena–Shokeir syndrome), arthrogryposis and constrictive dermatopathy, conditions that are typically characterized by inadequate or absent fetal movements.191,214

Even in the absence of fetal anomalies, short cords can increase the risk of adverse perinatal outcome, including placental abruption, preterm prelabor rupture of membranes (PPROM), intrapartum fetal heart rate abnormality, inadequate fetal descent in labor, operative delivery, uterine inversion and postpartum hemorrhage.213

It is important to note that these definitions of cord length are primarily based on examinations of the placenta and umbilical cord after delivery, rather than on prenatal ultrasound assessment.213 Furthermore, these measurements are typically obtained at term, which may differ significantly from measurements taken earlier in gestation. While some have attempted to assess umbilical cord length prenatally, this is an extremely challenging task that is difficult to standardize or reproduce. As such, routine measurement of cord length via prenatal ultrasound is not recommended and is often a qualitative rather than quantitative exercise. However, if the umbilical cord appears subjectively abnormally short (with only a small segment visible) or excessively long (with numerous free loops observed), a detailed fetal anatomy examination should be performed, with particular attention to fetal movements. In these cases, serial growth ultrasounds are also recommended to monitor fetal development.

Abnormal cord thickness

Lean umbilical cord

Thin or lean umbilical cords are often associated with FGR.185,218 In many such cases, there is marked deficiency of Wharton’s jelly, rendering the cord more susceptible to compression and increasing the risk of fetal acidemia. Oligohydramnios, frequently observed in growth-restricted pregnancies, can exacerbate this susceptibility by eliminating the cushioning effect of amniotic fluid, signficantly elevating the risk of fetal acidemia and stillbirth.

Silver and colleagues reported higher rates of smaller umbilical cord diameters in post-term pregnancies complicated by oligohydramnios.219 These pregnancies also exhibited a greater incidence of intrapartum fetal heart rate decelerations. Similarly, Raio and colleagues evaluated the cross-sectional area of the umbilical cord after 20 weeks' gestation in 860 patients.218 They identified a four-fold increase in small-for-gestational-age infants at birth among cases with lean umbilical cord. These pregnancies were also more likely to present with oligohydramnios at delivery and low 5-min Apgar score (< 7).

The umbilical artery cross-sectional diameter may be increased when there is a single umbilical artery.220,221

Thick umbilical cord

Thick umbilical cords with an abundance of Wharton’s jelly are often observed in pregnancies complicated by diabetes, fetal macrosomia and overgrowth syndromes such as Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome.222 Predanic and colleagues, in a small retrospective study, found that umbilical cord thickness was greater in fetuses with aneuploidy than in euploid fetuses.223

Although umbilical cord nomograms exist, umbilical cord thickness is not routinely measured during obstetric ultrasound examination.224,225 Observations such as a ‘thick’ or ‘lean’ cord are therefore typically subjective. However, when the umbilical cord appears unusually thick or thin, a detailed ultrasound evaluation of the fetus and placenta is recommended. In such cases, serial ultrasound examinations may also be advisable.

Marginal cord insertion

In some cases, the umbilical cord inserts close to the edge of the placenta, a condition known as marginal cord insertion (Figure 19; Video 10). The definition of marginal cord insertion varies, with some investigators using a distance of 2 cm from the placental edge, while others use 1 cm or 1.5 cm as the cutoff.226 In true marginal cord insertion, the fetal vessels remain protected by Wharton’s jelly throughout their entire course, with no exposed vessels.

19

Grayscale (a) and color Doppler (b) ultrasound images of marginal cord insertion, showing the cord inserting close to placental edge (arrows).

10

Grayscale and color Doppler imaging of marginal placental cord insertion.

Complicating the matter, studies often group velamentous cord insertions, in which vessels are unprotected for some distance, together with marginal cord insertions, in which the vessels are protected.227 Differentiating between these two conditions on obstetric ultrasound can also be challenging, further complicating the assessment of the clinical significance of true marginal cord insertion. Therefore, when a marginal cord insertion is suspected, it is crucial to differentiate it from a velamentous cord insertion, in which unprotected fetal vessels are seen traversing the membranes for a variable distance before inserting into the placental edge.

Some studies suggest that marginal cord insertions may be associated with an increased risk of adverse perinatal outcome, particularly FGR.228,229 Conversely, other studies have found no significant increase in risk.230,231,232,233,234 To compound the problem, some of the studies that show increased adverse outcomes were based on examinations of placentas after birth rather than by prenatal ultrasound.235 Importantly, the majority of isolated marginal cord insertions are associated with favorable perinatal outcome, allowing for patient reassurance.

In some centers, the identification of a marginal cord insertion prompts a third-trimester ultrasound to assess fetal growth and rule out FGR. This approach helps ensure appropriate monitoring and management while addressing potential concerns.

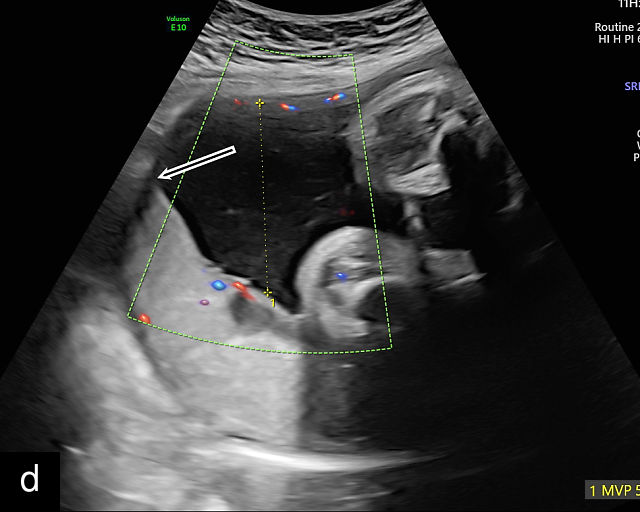

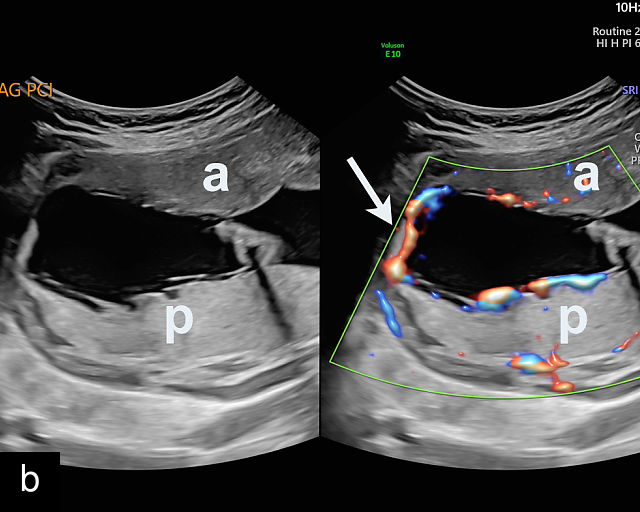

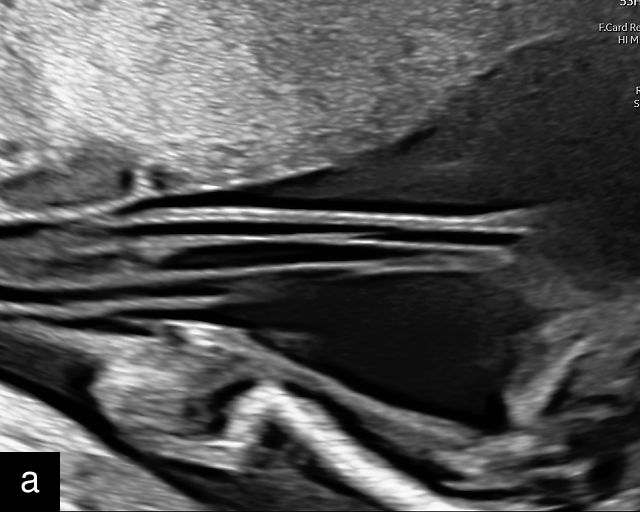

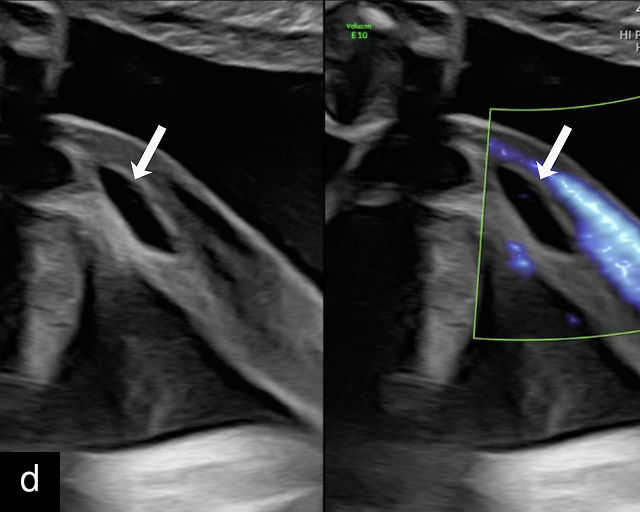

Velamentous cord insertion

When the umbilical cord inserts into the membranes rather than the main placental mass, it is known as a velamentous cord insertion (VCI).191 In this condition, unprotected fetal vessels traverse the membranes for a variable distance before inserting into the placental edge. Velamentous cord insertions are relatively common, occurring in approximately 1% of pregnancies and about 10% of twin pregnancies.191 A large population-based study from Norway reported a 1.5% prevalence of VCI in singleton pregnancies compared to 6.0% in twins.227 Risk factors for VCI include twin gestation, pregnancy conceived via assisted reproductive technology and advanced maternal age.34,236,237,238,239

VCI is associated with an increased risk of fetal structural abnormalities.240 When a VCI is identified, a detailed fetal anatomical survey is recommended. VCI is also linked to adverse perinatal outcomes, including intrauterine fetal demise, FGR, preterm birth and complications during delivery, such as cord avulsion leading to retained placenta and an increased risk of postpartum hemorrhage.241,242,243,244 VCI has also been associated with increased risks for cerebral palsy in the offspring.7 While rare, spontaneous rupture of VCIs has been reported, potentially resulting in stillbirth or other adverse outcomes. In the absence of vasa previa, however, labor and vaginal delivery are typically recommended. Serial ultrasound examinations to assess fetal growth are advised when VCI is detected during prenatal ultrasound. Importantly, VCI in monochorionic twins is associated with an increased risk for TTTS, selective FGR and birth-weight discordance.245,246,247

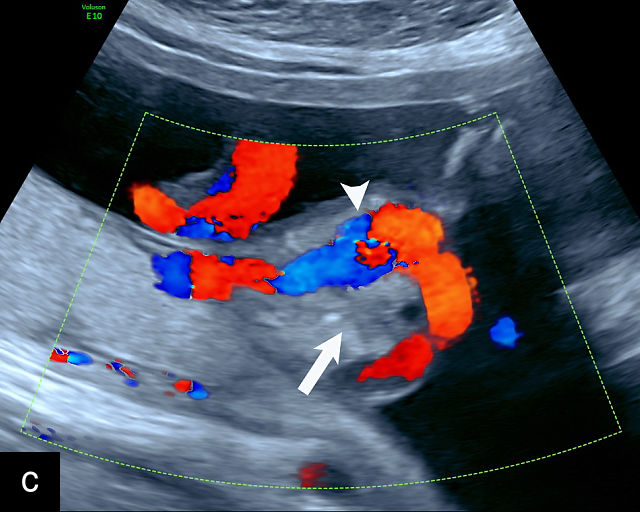

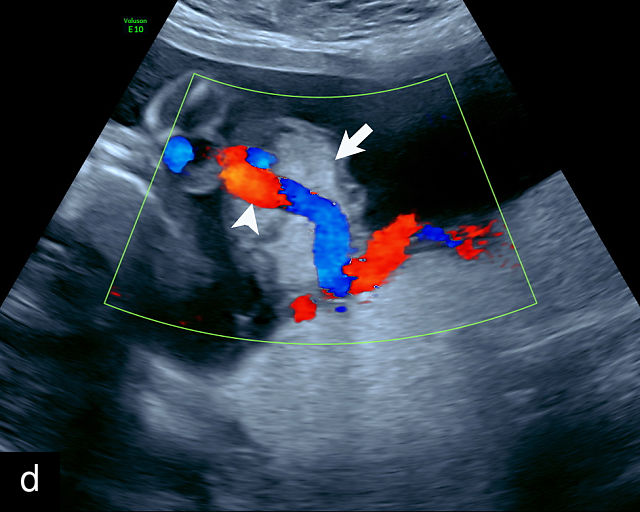

Ultrasound is the primary diagnostic method for identifying VCI. Normally, the cord inserts into the center or edge of the placenta and is fully protected by Wharton’s jelly. In contrast, a velamentous cord insertion is visualized on ultrasound as the cord inserting into the membranes, with unprotected fetal vessels running to the placental margin (Figure 20; Video 11). Color flow Doppler and three-dimensional ultrasound can enhance diagnostic accuracy. Velamentous cord insertion may also occur into the dividing membrane in a multifetal pregnancy (Figure 20e). When unprotected fetal vessels from a VCI cross over the cervix, the condition is termed vasa previa, posing a significant risk of fetal exsanguination if these vessels rupture. Because VCI is a strong risk factor for vasa previa, a color flow Doppler sweep over the cervix is recommended when VCI is identified. If concerns about vasa previa persist, transvaginal ultrasound with color Doppler may be performed for confirmation.30

20

(a–c) Grayscale (a) and color Doppler (b,c) ultrasound images of velamentous cord insertion. The cord inserts into the membranes (arrow), from where unprotected fetal vessels (arrowheads) traverse the membranes to insert into the edge of the anterior (a,b) or posterior (c) placenta (p). (d) Color Doppler ultrasound image of velamentous cord insertion, showing the cord inserting into the membranes posteriorly (arrow), from where unprotected fetal vessels (arrowheads) traverse the membranes to insert into the edge of the anterior placenta (p). (e) Ultrasound with color Doppler showing velamentous vessels (arrow) running through the dividing membrane in a dichorionic diamniotic twin pregnancy. The right image shows the placenta after delivery.

11

Color Doppler ultrasound imaging of velamentous cord insertion. The cord inserts into the membranes from where unprotected fetal vessels traverse the membranes to insert into the edge of the posterior (a) or anterior (b) placenta.

Nomiyama and colleagues conducted a study in which color Doppler screening of placental cord insertion was routinely performed on 587 patients during second-trimester anatomy scans.248 They successfully identified the placental cord insertion in 586 cases (99.8%) and correctly diagnosed five cases of VCI, with one false-positive result.248 The study reported a sensitivity of 100%, specificity of 99.8%, positive predictive value of 83% and negative predictive value of 100%. However, the study population in Japan had a significantly lower average body mass index (BMI) compared to populations in the Western world. Increased BMI, fetal position, uterine fibroids and posterior placenta may hinder visualization of the cord, making these results less generalizable to populations with higher BMI prevalence.

Sepulveda and colleagues evaluated 832 patients during the second and third trimesters using color Doppler and successfully visualized placental cord insertion in 825 cases (99%), diagnosing seven cases of VCI.249 These authors, in a separate study, also screened 533 pregnancies during the first trimester and correctly identified five cases of VCI.250

In the USA, consensus guidelines recommend assessing placental cord insertion during the second-trimester anatomical ultrasound examination when feasible. This approach is being increasingly recommended in other countries.251 At our center, this assessment has been routinely performed as part of the second-trimester anatomy scan for several years, and we strongly advocate for its inclusion as a standard component of the examination.

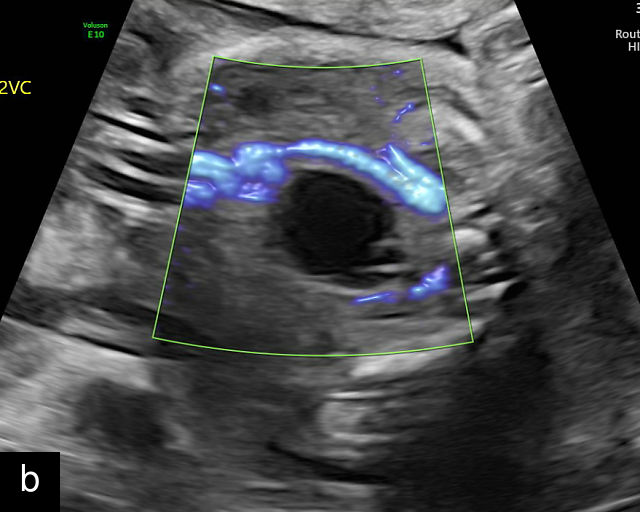

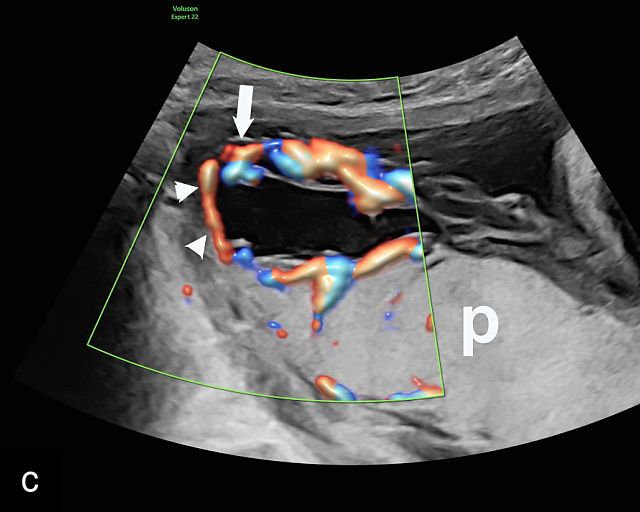

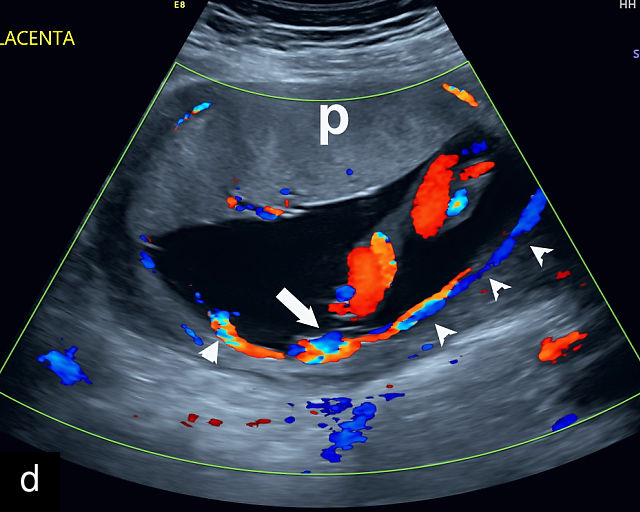

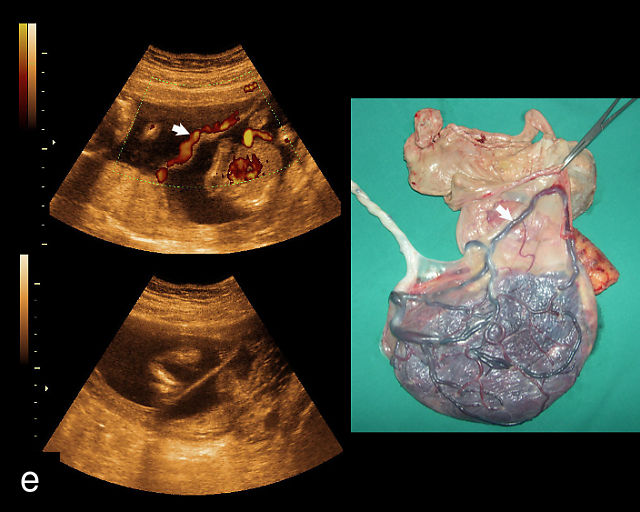

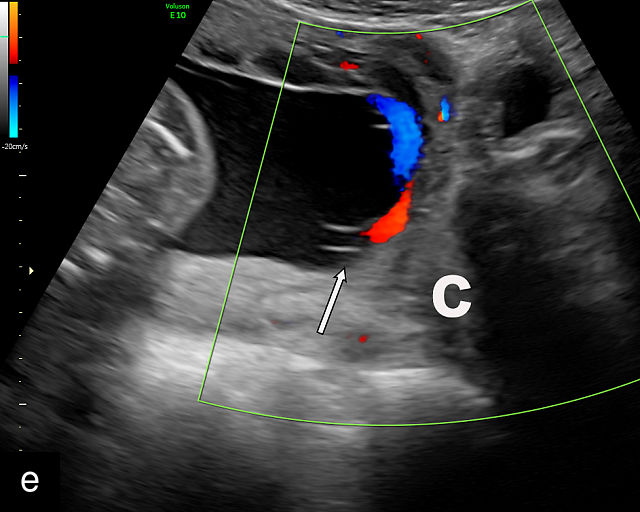

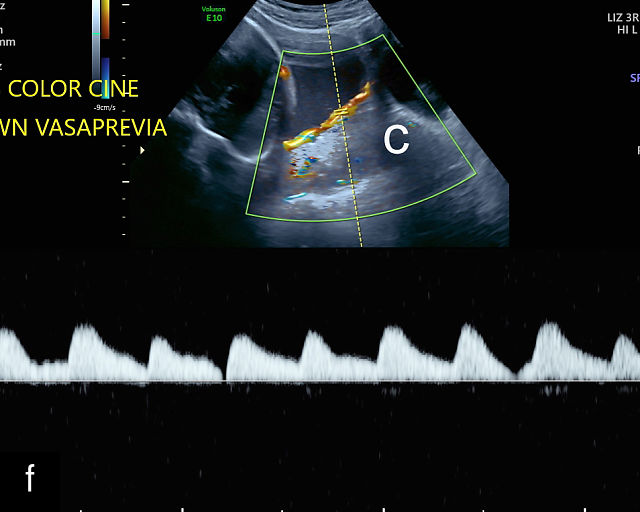

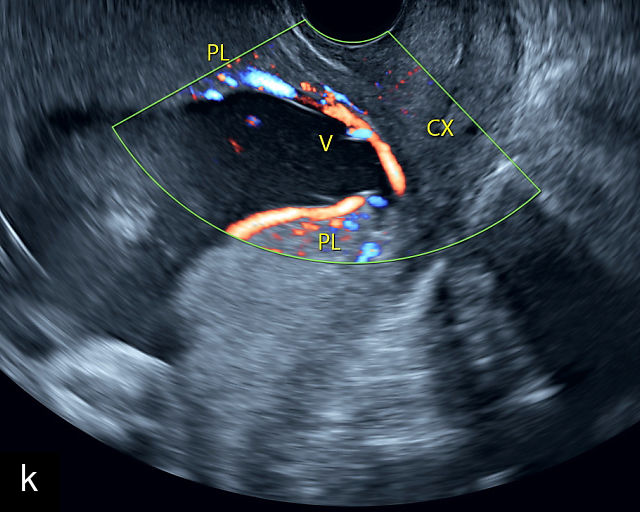

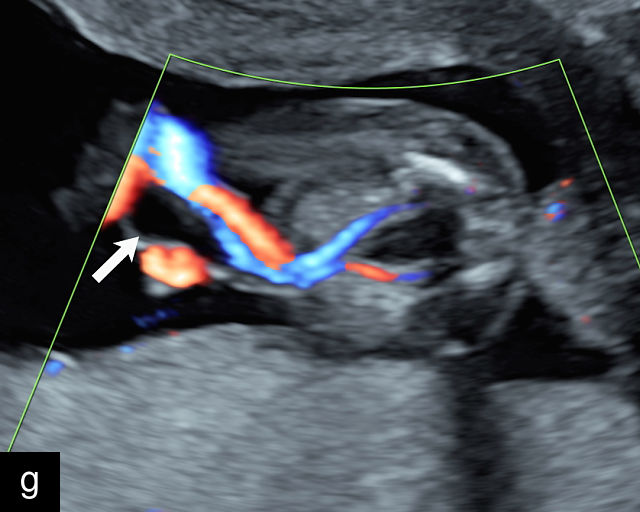

Vasa previa

Vasa previa refers to unprotected fetal vessels running through the membranes over the cervix.30,50,252,253 These vessels often rupture when the membranes rupture during labor or in late pregnancy, resulting in fetal hemorrhage and often exsanguination.252 As a result, this condition is associated with high perinatal mortality.35,252 A large study found a 56% perinatal mortality when vasa previa was not diagnosed prenatally.35 Prenatal diagnosis with ultrasound and cesarean delivery before labor or rupture of the membranes prevents this high perinatal mortality.254,255,256 Risk factors for vasa previa include second-trimester placenta previa or low-lying placenta, velamentous cord insertion, pregnancy resulting from in-vitro fertilization, multifetal gestation and placenta with accessory lobe.30,36,50,257,258,259,260,261

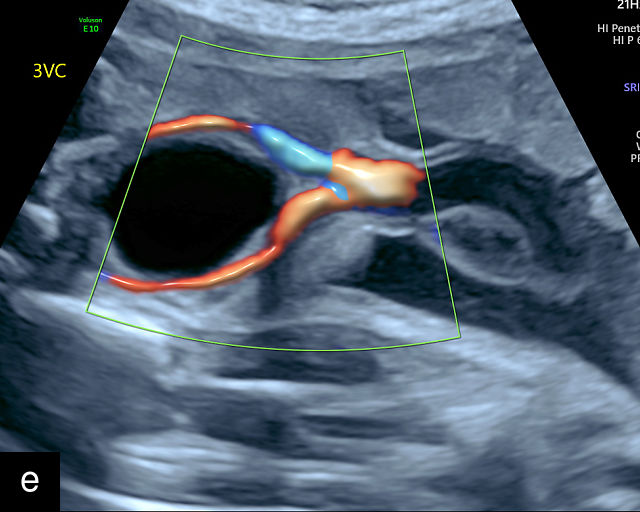

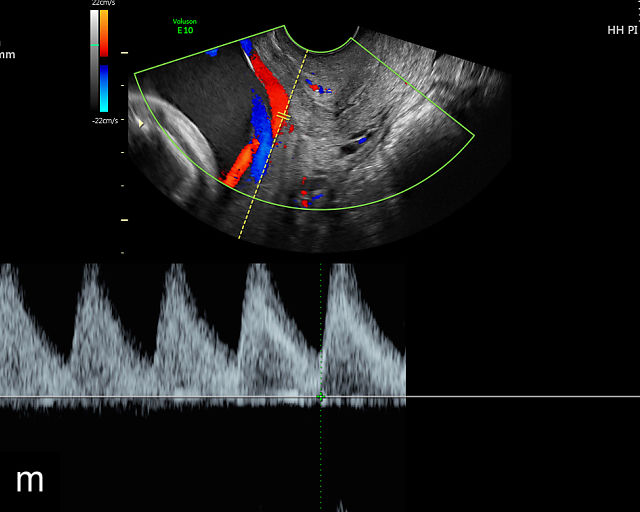

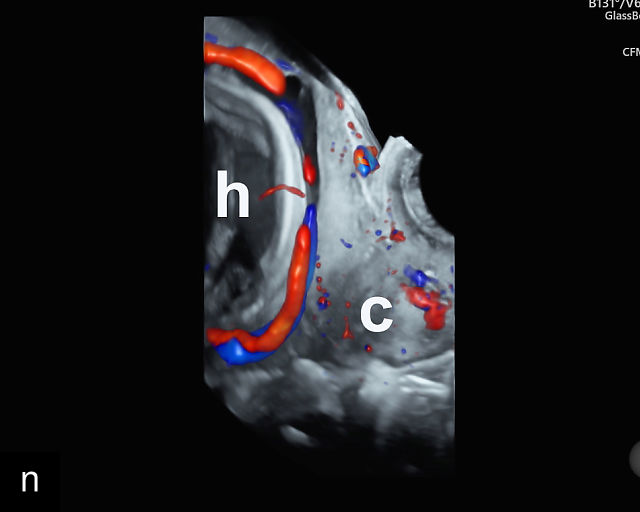

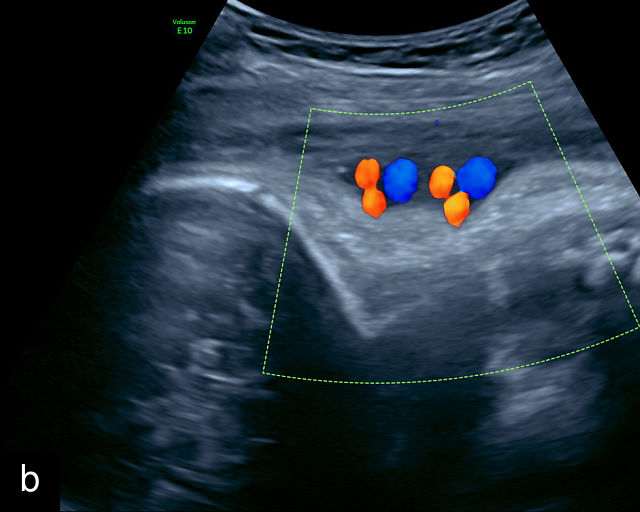

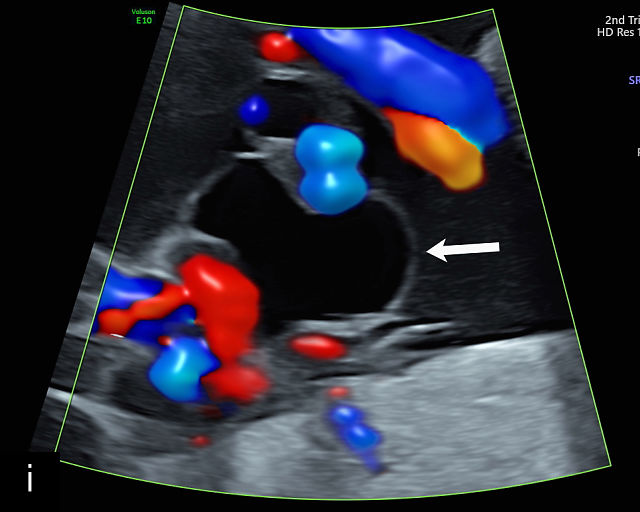

There are three types of vasa previa.30,262 In Type 1, the cord inserts into the membranes rather than the placenta. Unprotected vessels then traverse the membranes over the cervix to insert into the placenta (Figure 21a; Video 12). In Type 2, unprotected vessels running through the membranes over the cervix connect the main placental lobe with an accessory lobe (Figure 21b).263 In Type 3, there is generally a normal placental cord insertion, and unprotected vessels exit one placental edge, run through the membranes over the cervix and then boomerang to insert into the placental edge at another site (Figure 21c).25,28,29,264 Regardless of the type, all these expose the fetus to the same risks.

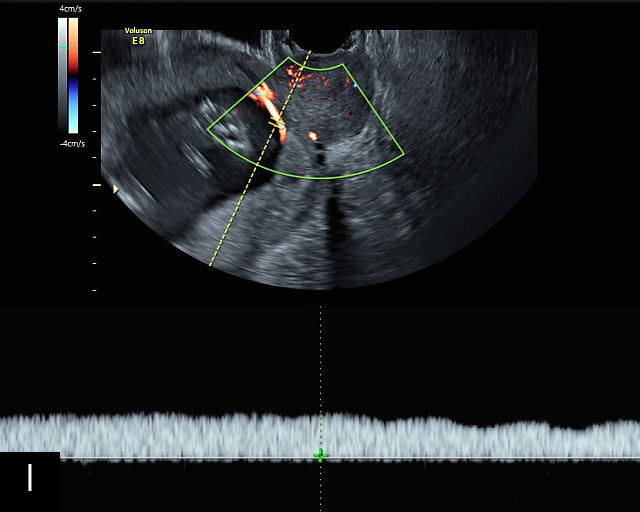

21