This chapter should be cited as follows:

Bergh A-M, Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.414253

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Obstetrics Module

Volume 3

Elements of professional care and support before, during and after pregnancy

Volume Editor: Professor Vicki Flenady, The University of Queensland, Australia

Chapter

Effective Health Promotion and Health Education

First published: February 2021

INTRODUCTION

Two topics on which most members of the public consider themselves ‘experts’ are nutrition and education. The result of this is the circulation of many misconceptions and conflicting messages. With the advent of the internet, the amount of health information has increased exponentially by day, which poses challenges in terms of judging the quality of information to which clients of health services are exposed. Therefore, effective health promotion (HP) and health education (HE) is an overwhelming topic. Related and overlapping terminologies that further complicate the understanding of HP and HE include facilitation, counseling, mentoring, guiding, coaching, advising, teaching, communication, etc. It is therefore inevitable that some of the points in this chapter fall within the ambit of actions related to these other terminologies, especially with regard to counseling and communication.

There are many ways to approach issues related to HP and HE. The aim of this chapter is to introduce the reader to the concepts of health promotion, health education and health literacy as espoused by the World Health Organization (WHO) and to apply basic ideas to the reproductive life cycle of women, starting from preconception and continuing through to the postnatal period.

Because of the centrality of human behavior in HP and HE, it is not possible to describe ‘effectiveness’ in uniform terms. In order to devise effective HP and HE programs it is often wise to do a needs assessment for a specific context, as one cannot always rely on the available evidence base. What works in high-income countries, may not work in low- and middle-income countries. For example, where the emphasis in programs in high-income countries may be on client autonomy in making decisions during pregnancy, labor or the postnatal period, the emphasis in low- and middle-income countries may be on enabling a health system that promotes social justice and access to antenatal and postnatal health care and delivery in a health facility. In settings of diversity, cultural competence of health care providers to provide appropriate reproductive care, including health education, is essential,1 whereas the communication skills required in monocultural settings may be different.

HP and HE are context dependent. One size does not fit all and interventions need to be tailored to the realities of different countries and should be embedded in national health and implementation strategies.2 This chapter outlines a number of principles and practical common sense approaches that could be applied in most contexts. The target readers are health professionals, including policy makers, health managers, public health specialists, physicians (especially medical practitioners, family physicians and obstetricians), nurses, midwives, health promoters, health educators and other allied and rehabilitation health professionals. The focus is to stimulate readers’ reflection on what effective HP and HE mean for their context and scope of practice and to identify what readers can do in their own setting at the level of the health system where they work.

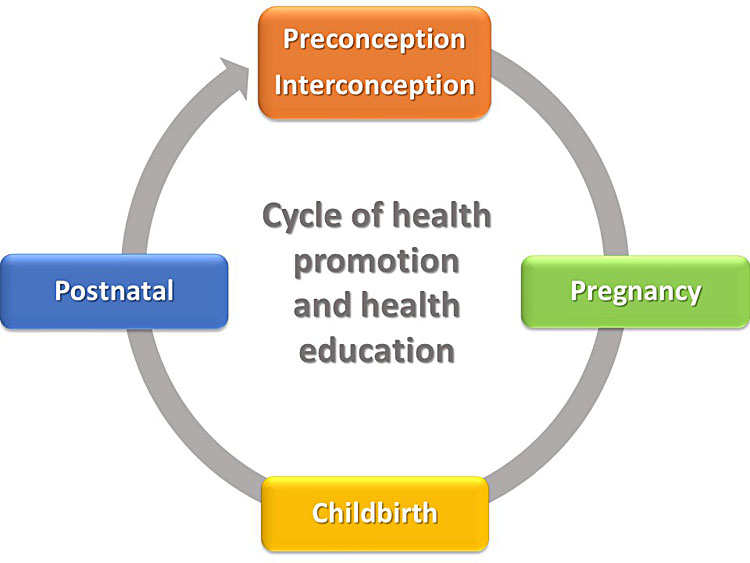

The key recipients of HP and HE are women in their childbearing age, with their families and communities as secondary target audiences. This cycle is illustrated in Figure 1. Preconception care refers to the “provision of preventive, promotive or curative health and social interventions before conception occurs”,2 whereas interconception care refers to the interventions a woman should be exposed to between pregnancies.2

1

Health promotion and health education in the context of the reproductive health cycle.

The rest of the chapter is devoted to unpacking key concepts, golden-thread health messages throughout the reproductive life cycle, content for specific stages of the life cycle, health promotion and health education interventions and methods, and examples of potentially effective interventions. The boxes in blue contain reflective activities for the reader to position the information provided in relation to his or her work context.

UNPACKING KEY CONCEPTS

The three central concepts used in this chapter are health promotion, health literacy and health education. We use the following definitions as point of departure:

“Health promotion is the process of enabling people to increase control over, and to improve, their health. It moves beyond a focus on individual behavior towards a wide range of social and environmental interventions.”3

“Health literacy is the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.”1

“Health education is any combination of learning experiences designed to help individuals and communities improve their health, by increasing their knowledge or influencing their attitudes.”4

According to WHO, health promotion has three components: good governance for health; health literacy; and healthy cities.5 In terms of reproductive health, the proximal focus of this chapter is on good governance and health literacy, whereas urban planning, preventive health measures and access to primary health care facilities provide the healthy-city, distal backdrop for the care of women of childbearing age. The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion, 1986 states that health can only be improved if basic requirements for health are met, namely peace, shelter, education, food, income, a stable ecosystem, sustainable resources, social justice and equity.6 HP spans the continuum of comprehensive primary health care with its protective, preventive, curative, palliative and rehabilitative dimensions.7

The Pender Health Promotion model in nursing is widely used for understanding what is required of health professionals. The focus should not only be on helping people prevent illness and achieve higher levels of well-being, but also on pathways to follow to pursue better or ideal health. Pathways include the provision of positive resources by health care workers to help clients. Essential to HP are self-initiated changes to the characteristics of individuals and their environment. Health care workers are part of the interpersonal environment that influences people throughout their lifespan. Pender also provides examples of templates for clinical assessment with a view to develop health promotion plans.8

Figure 2 provides a graphic depiction of the conceptualization of terminologies in this chapter. HP, HE and health literacy are overlapping concepts and all three are needed for devising messages aimed at population, group and individual level. The health authority of a particular state or country – for example, the Ministry of Health – has to formulate policy. Good governance will ensure that the policy is associated with consistent health messages that will prevail in all HP and all HE across all levels of the health system, from health campaigns to group activities to individual consultations. This also assumes appropriate training of and regular updates for health care providers. In the individual consultation, the health care provider and the woman will ideally come to realistic decisions that will empower her to do the best for her circumstances. For example, if she does not have the means to feed herself optimally, the provider should explore alternatives with her in order for her to make the most affordable choices without feeling guilty.

2

Relationship between the key concepts.

“Good governance will ensure that policy is associated with consistent health messages that will prevail in all health promotion and all health education across all levels of the health system, from health campaigns to group activities to individual consultations.”

At the center of effective HP and HE are client health literacy skills needed for meaningful interaction with health care providers. According to the United States Committee on Health Literacy, these skills are needed for dialogs and discussions, reading health information, interpreting charts (e.g. a pregnancy chart or a baby’s growth chart), using tools (e.g. a thermometer or oxygen) and calculating timing or dosage of medicine.9 Women require knowledge of their bodies, the nature and causes of diseases9 and health topics related to pregnancy, childbirth and postnatal care. They also need to understand how lifestyle factors9 such as smoking, alcohol consumption, diet, physical activity and adherence to specific treatments (e.g. the prevention of mother-to-child-transmission) can influence pregnancy outcome and the well-being of the newborn. According to Cowan, “Without comprehension, adherence is by chance rather than by choice”.10

Health education is often considered a particular health promotion strategy or intervention that influences individuals’ knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and skills.11 The objectives of HE is to inform and motivate people and to guide them into action,12 in other words, to create change.11 HE can be one-on-one, in a group or as part of population-based health promotion campaigns. Health education in women’s reproductive life cycle can take place in different settings. In low- and middle-income countries where collective activities are part of the culture, health care facilities and community-based organizations are important vehicles for group HE. In high-income countries HE is more individualistically focused and women are more likely to seek health information from other resources available to them, including the internet and structured parenting classes. Even people with advanced literacy skills struggle to process the overwhelming amount of health information that is available. If the information is provided in a stressful or unfamiliar situation, not much may be retained.9

The Ottawa Charter describes health promotion action as building healthy public policy, creating supportive environments, strengthening community actions, developing personal skills and reorienting health services.6 Can you think of how these actions are relevant with regard to the professional care and support needed before, during and after pregnancy in the context where you work? Reflect on a few practical examples.

GOLDEN THREADS FROM PRECONCEPTION TO POSTNATAL CARE

One of the purposes of HP and HE in low- and middle-income countries is to prevent maternal and neonatal death and disease. Mwaniki et al. proposed a five-pronged framework that expands on the three-delay model for understanding and preventing maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality. The first prong entails a broad focus on primary prevention strategies that include clients’ comprehension of the vertical transmission of certain viral and bacterial infections (e.g. HIV/AIDS and group B streptocuccus) and the importance of chemoprophylaxis. Prongs 2 to 4 encompass the three delays that is a form of secondary prevention during pregnancy, namely delays in decision to seek care, delays in reaching the point of care after deciding to seek care and delays in the provision of adequate care. Prong 5 relates to tertiary prevention and refers to post-discharge follow-up and rehabilitation.13 Health messaging around these prongs is discussed in the next section.

There are certain key health topics to cover in HP and HE endeavors involving women of childbearing age. The content of the messages should be adapted to the specific point in the reproductive life cycle where a woman finds herself – before, during and after pregnancy. The content of some messages needs adaptation to a specific context to align messages with existing government policies and levels of services available. When developing general health messages and HP and HE interventions, there are two main focus areas to explore:

- Access to care and how that may influence the health seeking behaviors of a woman at any stage in the woman’s reproductive life cycle; and

- Health topics that run though all the stages of the reproductive health cycle to include in health messages.

An example to illustrate the first focus area relates to the WHO guidelines for an increased number of antenatal contacts towards the end of pregnancy.14 If a government makes that the new policy, it should ensure that the existing health personnel would be able to cope with the increased workload in the health services or more staff positions should be created (with the potential of filling those positions and affording the increase of expenditure on salaries).

Governments are responsible for setting policy and developing consistent key health messages around policy. The same messages should be used in HP and HE at all levels, with the level of language adapted to the level of different audiences. Conflicting messages can render HP and HE efforts ineffective and should be avoided. Information around health topics to include in the HP and HE activities in all settings are the following:

- Nutrition (e.g. own nutrition, breastfeeding);

- Birth spacing and contraception;

- Lifestyle issues (e.g. smoking, substance use, physical activity);

- Safe sex and sexually transmitted infections, including HIV;

- Mental health;

- Newborn care and parenting.

Issues to cover in specific circumstances or contexts include:

- Adherence to medical treatment or lifestyle changes;

- Specific types of infectious diseases (e.g. hepatitis B and C, malaria, dengue and TB) and how to avoid or treat them.15 Attention to certain emerging infectious diseases may also be needed;16

- Harmful cultural practices (e.g. herbal concoctions to induce or accelerate labor, female genital mutilation).17,18

In certain contexts, the same midwife or group of midwives supports a woman throughout her reproductive life cycle.19 HP and HE are an integral part of their day-to-day functioning.

In the context where you work:

- What are the challenges in addressing general health topics like nutrition, contraception and lifestyle issues? What are possible solutions?

- How are specific types of infectious diseases included in HP and HE activities? How consistent are current health messages? How could they be improved?

- What are harmful practices in your context? Are they addressed adequately in HP and HE activities?

THE ‘WHAT’ – CYCLE-SPECIFIC HEALTH PROMOTION AND EDUCATION CONTENT

This section is based on the messaging content areas that are contained in the WHO’s guideline documents for preconception care, antenatal care, a positive birth experience and postnatal care. Information in specific chapters in The FIGO Continuous Textbook of Medicine Series and this volume (Elements of professional care and support before, during and after pregnancy) could also guide on the choice of topics and information to include in appropriate health messages.

PRECONCEPTION CARE

The WHO outlines preconception care as “the provision of biomedical, behavioral and social health interventions to women and couples before conception occurs, aimed at improving their health status, and reducing behaviors and individual and environmental factors that could contribute to poor maternal and child health outcomes. Its ultimate aim is improved maternal and child health outcomes, in both the short and long term”.2

Preconception care (including interconception care) is also termed pre-pregnancy care. Vehicles of preconception care include health education and promotion, vaccination, nutritional supplementation and food fortification, the provision of contraceptive information and services, and medical and social screening, counseling and management.2

The WHO’s proposed package of preconception care includes various health areas with a HP and HE component (Table 1). Although they are relevant in all countries, HP and HE programs and methods of delivery for these topics may vary in approach and format in different countries. Countries may also prioritize these areas in HP and HE interventions in different ways.

1

WHO package of preconception care.2

Nutritional conditions |

Tobacco use |

Genetic conditions |

Environmental health |

Infertility/sub-fertility |

Interpersonal violence |

Too-early, unwanted and rapid successive pregnancies |

Sexually transmitted infections (including HIV) |

Mental health (including epilepsy) |

Psychoactive substance use |

Vaccine-preventable diseases |

Female genital mutilation |

PREGNANCY CARE

The pregnancy period provides the optimum window for HP and HE activities related to pregnancy and childbirth because of the immediacy of an expected childbirth. This is the period for preparing women and communities regarding risk reduction in pregnancy and at childbirth, on appropriate health-seeking behavior and on childbirth, newborn care and parenting. Included will be preparation for the two delays related to client behavior. With regard to delays in the decision to seek care, health education should focus on warning or danger signs in pregnancy and early neonatal life, the causes of these conditions, and what to do when symptoms appear. Health education to avoid delays in arriving at a health care facility would include having a transport plan for getting to the health facility for treatment or delivery and addressing cultural practices that may cause a delay (e.g. where a woman must have the permission of her husband to seek care). HP in this regard would also include efforts from the health system to minimize delays in reaching a health care facility and using community health workers and similar cadres to assist the pregnant woman or the woman in labor to reach a site with skilled birth attendance. The quality of antenatal care is a precursor of a positive experience of quality of care during childbirth.

In 2016 WHO introduced its new recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience,14 prioritized around person-centered health care, the well-being of women and families, and positive perinatal and maternal outcomes.20 The core package of routine antenatal care with 39 recommendations, some general and some context specific, are organized around five types of interventions.14

- Nutritional interventions with key health messages include healthy eating and keeping physically active during pregnancy. Messages on increasing daily energy and protein intake to reduce the risk of newborn low birth weight are appropriate for undernourished populations. Other interventions such as iron, folic acid, calcium and vitamin A supplementation should also be accompanied by an explanation to women of the reasons for supplementation and the importance of taking the supplements.

- Maternal and fetal assessments provide an opportunity for health education in the form of explanations for doing an ultrasound scan and certain tests, e.g. for anemia or asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB). Where appropriate, counseling on specific lifestyle issues or conditions may be needed, e.g. with regard to intimate partner violence, gestational diabetes mellitus, tobacco and substance use, HIV and TB. Health authorities have a responsibility to ensure that the necessary equipment and stock are continuously available to fulfill basic requirements such as blood pressure measurement and urine testing at each antenatal contact and women should be empowered to insist on quality antenatal care.

- When preventive measures are taken, e.g. antibiotics for ASB and tetanus toxoid vaccination, appropriate explanations should be provided to women and families.

- Common physiological problems and safe treatments should be included in health promotion and health education activities at population, groups and individual level. These include nausea and vomiting, heartburn, leg cramps, lower back and pelvic pain, constipation, varicose veins and edema. Messages should be tailored according to what is available and to women’s preferences.

- Women also need to receive consistent messages to improve the utilization of quality antenatal care services. These should include warning signs that require immediate health-care seeking. Currently WHO recommends a minimum of eight antenatal contacts instead of the previous recommendation of four to reduce perinatal mortality and improve women’s experience of care. If the health message to the population is increased contacts, the health system must be able to deliver on this. In some settings the mobilization of communities could support pregnant women and address barriers to reaching care by means participatory women’s groups, also known as support groups, and antenatal home visits.

Messages around the preparation and readiness for birth should also be included at antenatal contacts. Some messages should be tailored one-on-one in the consultation with the pregnant woman and should include negotiated and shared decision making. For example, has a birth plan been discussed with each pregnant woman? Does this plan include transport options to get to the health facility when the woman goes into labor? What should the pregnant woman acquire and take along to the health facility? In some settings, for example, families have to buy their own birth kits. Other messages around danger signs in pregnancy, healthy eating and preparing for breastfeeding are often included as group health-education topics.

A topic that has been largely invisible in HP efforts in pregnancy is fetal well-being and the prevention of stillbirths. One possible reason is that only a small number of health professionals (obstetricians and midwives) are directly involved with this. In the past decade there have been numerous calls for action on ending preventable stillbirths, including two Lancet series on stillbirths21,22 and the Every Newborn series.23 Simultaneously there has been a push for the promotion of more awareness among the general public on fetal well-being, causes and prevention of stillbirths, and dealing with bereavement. There are many country initiatives and organizations to support parents, many of which belong to the International Stillbirth Alliance. In high-income countries numerous resources on, for example, fetal movement and sleeping position are available to parents, such as those developed by Tommy’s24 and the Baby Buddy app.25 Health professionals are encouraged to keep updated with the latest research on the prevention of fetal mortality and stillbirths in order to ensure they propose measures that have been rigorously evaluated.26

INTRAPARTUM CARE

The WHO document on intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience includes recommendations related to communication, counseling and education of women preparing for childbirth or who are in labor to enable informed choice and continuous support:19

- “Effective communication between maternity care providers and women in labor, using simple and culturally acceptable methods”.19 The woman should know the name of her health care provider. Interaction with a woman and her family should include information in a clear and concise manner, ensuring that she understands her choices, including the presence of a birth companion of her choice. Health care providers should explain procedures such as pelvic examinations and seek consent for performing them. The woman and her family should be updated on what is happening and should be aware of available mechanisms for addressing complaints. Maternity care staff should be trained in interpersonal communication and counseling skills to achieve an appropriate level of competency.

- “A companion of choice ... for all women throughout labor and childbirth”.19 Drafting a birth companionship policy and implementing it may require different advocacy messages, especially in settings where there are privacy concerns and limited resources. Where birth companions are allowed, health care providers should provide clear explanations on how to support the woman during labor and childbirth.

- Health care providers should provide clear explanations to women throughout all the stages of labor. Some examples include the variability between women of the duration of the different stages of labor, pharmacological and non-pharmacological pain relief options and the purpose, technique and findings of certain procedures like pelvic examination and auscultation.

POSTNATAL CARE

Although the first 6 weeks after delivery are normally considered the postnatal period, HP and HE continues long after this period, especially with regard to the care of the baby and parenting skills. Mwaniki et al.’s fifth prong (tertiary prevention) makes provision for postdischarge/hospitalization follow-up and rehabilitation that include follow-up and treatment of obstetrics complications (including obstetric fistulas). Multiple cadres of health professionals like occupational therapy, physiotherapy and psychologists will be involved with ongoing HE and support in the case of long-term impairment of mother or baby.13 All women need to understand the contacts for mother and newborn in the postnatal period: on day 3 (48–72 hours), between days 7 and 14, and 6 weeks after birth.27

The WHO recommendations on postnatal care of the mother and newborn include a recommendation that in the case of facility-based birth, “mothers and newborns should receive postnatal care in the facility for at least 24 hours after birth”.27 This is the opportunity to provide hands-on education and demonstration on the art of breastfeeding and to reinforce messages that should have been received since preconception care such as the importance of exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months. In this period, step 10 of the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative could be strengthened, with referral to support groups or services in the community that can reinforce important health messages and strengthen facility-community links.28 During the health-facility stay, information and reassurance should be given around the physiological process of recovery after birth and common health problems.27 This education should include danger signs for mothers and babies and, where relevant, the special needs of sick, preterm and low birth weight babies during their stay in and after discharge from hospital and how and why they are treated according to specific protocols.

Although parenting education should start before the birth of the baby, immediate health messages and demonstrations to include in pre-discharge counseling and education include the following:27,29

- Feeding;

- Cord care;

- Delayed bathing (until at least 24 hours after birth);

- Appropriate clothing of the baby for ambient temperature (i.e. one to two layers of clothes more than adults, and a hat or cap);

- Normal infant behavior and development, including crying, sleeping and growth;

- Preventive care: immunization as per the existing country or WHO guidelines, transport safety, avoidance of areas with smoke;

- How to communicate, interact and play with the newborn.

In a Cochrane review on postnatal parental education for optimizing infant general health and parent–infant relationships Bryanton et al. state that all parents are not exposed to positive parenting behavior through social support or role models and they need to acquire new knowledge and skills in order to become competent and confident. They continue: “Education by health personnel has the potential to play a key role in assisting new parents in their parenting efforts”.29

THE ‘HOW’ – HEALTH PROMOTION AND HEALTH EDUCATION INTERVENTIONS

We are used to the term ‘medical intervention’ as meaning some form of manipulation, pharmacological, surgical or other treatment that may be needed during pregnancy, childbirth or thereafter. It is defined as “the act or fact or a means of interfering with the outcome or course especially of a condition or process (as to prevent harm or improve functioning).”30 In relation to HP, an intervention is often related to some systematic and programmatic form of action with particular objectives that would improve certain maternal and neonatal outcomes31 at the population level. In order to achieve this, elements of the intervention should also be applied at the level of individuals and groups. Table 2 lists WHOrecommendations for maternal and newborn health promotion interventions.

2

WHO recommendations for maternal and newborn health promotion interventions.32

Birth preparedness and complication readiness |

Male involvement interventions for maternal and newborn health |

Interventions to promote awareness of human, sexual and reproductive rights and the right to access quality skilled care |

Maternity waiting homes |

Community-organized transport schemes |

Partnership with traditional birth attendants |

Providing culturally appropriate skilled maternity care |

Companion of choice at birth |

Community mobilization through facilitated participatory learning and action cycles with women’s groups |

Community participation in maternal death surveillance and response |

Community participation in quality-improvement processes |

Community participation in program planning and implementation |

Different approaches, associated with the objectives of a particular health promotion program, influence the design of a program. The approaches could focus on medical or preventive measures, behavior change, education, empowerment or social change.31 In the context where you work, could you identify examples of different approaches that have been used in different programs, especially in maternal and newborn care programs?

Although HP activities could comprise a single activity, the use of a variety of activities is more common in systematic interventions. Be realistic and start where an intervention is needed and feasible2 and with activities that would contribute to the outcomes and impact of the intervention in terms of effectiveness and efficiency.31 Activities could be related to communication, education, behavior modification, environmental change, regulation, community advocacy, organizational culture, incentives and disincentives, health status evaluation, social and technology-delivered activities.31 HE could be one of the activities of a HP intervention or it could be the intervention itself. A basic principle is that no HP or HE activity should cause harm. For example, women should not receive the message of eight contacts during antenatal care if the health services cannot carry the additional burden moving from four to eight visits and the end effect is less health-seeking behavior as a result of not receiving quality care during all visits.

“Be realistic and start where an intervention is needed and feasible and with activities that would contribute to the outcomes and impact of the intervention in terms of effectiveness and efficiency.”

Part of intervention planning would be to consider costs when identifying delivery channels and mechanisms of key messages. Channels and mechanisms could include primary care, programs of community-based and faith-based organizations, existing ministry of health programs, social welfare programs, education systems and workplace programs. Interventions should furthermore be appropriately packaged for the intended target groups and modes of delivery, should attract adequate attention and should be integrated into existing programs. Health messages should be based on the latest evidence available and tailored to the language and educational level of the target audience. It is also important to deliver interventions and messages in a client-centered way that does not stigmatize or undermine the key decision-making roles of women and their families or groups that are at risk.2

APPROPRIATE HEALTH PROMOTION AND HEALTH EDUCATION METHODS

There are many vehicles and methods for HP and HE, and examples abound. The choice of method is determined by the aim of the promotion and education efforts. Population-based health promotion often uses mass media such a television, radio and popular magazines to reach large numbers of people. Social media are becoming more popular and information can be received by means of SMS, Facebook, YouTube, Twitter and others. Embedding HP and HE around the reproductive lifecycle of women in existing community programs and using health cadres such as community health workers, health promoters and youth counselors are ways to reach groups of people with limited access to health facilities and that are otherwise hard to reach.2

Routine health care visits by groups and individuals is an ideal opportunity to include HE with HP messages.2 One example is the voluntary counseling and testing of women or couples for HIV. Other methods for reaching individuals and groups include interaction by phone or face-to-face, printed material or videos.29 The Global Health Network has produced a number of videos on specific topics for mothers that are free to download and that can be played even on basic phones.33 Table 3 provides a summary of a few aims of HP interventions and appropriate HE methods for each.

3

Matching the aims of a health promotion intervention with appropriate health education activities.31,34

Aim | Vehicles for delivering messages | Methods | Learning materials |

Raise awareness | Campaign Mass media | Talks Group work & buzz groups Role play and drama Traditional methods* | Displays/exhibitions |

Provide information | Campaign Mass media Training & facilitation | Groups discussions One-to-one teaching Demonstration | Information, education and communication (IEC) materials** |

Promote self-empowerment | Training & facilitation Counseling | Skills training & facilitation (assertiveness & social skills) Values clarification Practical work*** Traditional methods | IEC materials |

Change attitudes and behavior | Campaign Mass media Training & facilitation Counseling | Group work Group or individual therapy Self-help groups One-to-one instruction Traditional methods Skills training | IEC materials |

Change the physical or social environment | Planning and policy making Enforcement of laws and regulations Environmental measures Organizational change | Advocacy Lobbying Pressure groups Community-based work Positive action for underserved groups | IEC materials |

* Traditional methods: poems, stories, song and dance, games, fables, puppet shows; ** Information, education and communication (IEC) materials: Visual (printed): leaflets/pamphlets, booklets, posters, displays, exhibitions, and

Audio and audio-visual: radio talks, videos, television show, mHealth messages; *** Practical work: decision-making, simulation, gaming, role play, drama, demonstration.

Use Table 1 to identify the aims of health promotion interventions in which you have been involved.

- Which of the health education methods did you use?

- How successful were they?

- What would you do differently if you have to repeat an intervention?

Women in the age group of the reproductive health cycle and their significant others are adults and engagement with HP and HE should be based on the principles of adult learning. Malcolm Knowles, a pioneer in adult education, listed six characteristics that are common to most adult learners. He stated that adults are:

- Autonomous and self-directed and must be actively involved in the learning process as facilitators rather than fact generators;

- Experienced and come with a wealth of knowledge and life experiences on which educators should build;

- Goal-oriented and appreciate well-organized educational programs that relate to their goals;

- Relevancy-oriented and should see the applicability of what they learn to their work or other responsibilities;

- Practical and prefer to learn by doing rather than listening to lectures;

- Deserving of respect with appropriate acknowledgement of appreciation for their prior learning and experience.35

Women and their significant others need to be enabled to learn. The following are questions for self-reflection by the health care provider:

- How do I motivate clients?

- How should I reinforce messages?

- How do I assure that information and skills are retained?

- How can I ensure that learning is transferred to everyday life?35

EXAMPLES OF POTENTIALLY EFFECTIVE HEALTH PROMOTION AND HEALTH EDUCATION INTERVENTIONS

In each country there are many examples, some with a more sound evidence base than others, of HP interventions related to maternal and newborn health that include HE. In this section, we only highlight three types of interventions illustrated by means of specific examples for which there is some evidence of acceptability, success or effectiveness. They are group-based antenatal care (e.g. CenteringPregnancy®), mobile health (mHealth) interventions spanning from pregnancy through to postnatal care (e.g. MomConnect) and postnatal breastfeeding support groups that are operating in different formats across the globe.

Group-based antenatal care

Group antenatal care models have been widely implemented as an interactive way of empowering women to take control of their own health through group engagement and to socialize with other pregnant women. One of the popular and most widely implemented models in high-income countries is CenteringPregnancy® and CenteringPregnancy Plus with the three main components: (1) health assessment, (2) education, and (3) peer support. At the first antenatal visit a woman’s medical history is reviewed and a physical examination and the laboratory tests are done. Eight to 12 women are grouped together according to their expected date of delivery at around 16 weeks of gestation. They attend their appointment together about 10 times during their pregnancy. A session lasts about 2 hours and starts with self-assessment and individual assessments with the obstetric provider (30–40 minutes). This is followed by a group discussion (60–75 minutes) around gestation-related topics and parenting concerns that is co-facilitated by two providers, often an obstetrician, a nurse practitioner or a certified nurse-midwife. At the end of a session time is allocated to additional individual follow-up if needed.36,37,38,39,40 This model delivers a quadruple aim of improved patient experience, quality of care, cost containment, and provider satisfaction.38

Studies using CenteringPregnancy® as an intervention, with and without a control group, have been conducted on various subgroups of pregnant women and included descriptions like high risk, underserved, low income, Africa American, Hispanic, immigrants, limited English skills, adolescents, opioid addicts, diabetes, in the military. Outcomes measured by these studies included incidence of preterm birth, attendance of antenatal visits, weight trajectories of pregnant women, satisfaction with care, increased knowledge of pregnancy, utilization of family planning services and uptake of long-acting reversible contraception, breastfeeding initiation and exclusive breastfeeding, psychological well-being, diabetes, tobacco use36 and health care compliance.41 Most studies reported positive outcomes.

Two pilot studies on the implementation Centering Pregnancy-Africa have also been conducted in sub-Saharan Africa (Nigeria, Malawi and Tanzania).42,43 Both studies concluded that this was “a promising intervention to increase uptake of maternal health care services in northern Nigeria”42 and “feasible in resource-constrained, low-literacy, high-HIV settings in sub-Saharan Africa”.43 However, low- and high-come countries faced implementation challenges. Studies in high-income countries listed the following challenges that could lead to compromises and modifications of the model that affect relationships and group cohesion and may jeopardize optimal health outcomes: poor staff understanding of roles and expectations resulting in poor integration within clinic structures;44 scheduling changes;45 inadequate resources;46 bureaucratic organization structures and lack of buy-in;47 and slow adoption of the model by staff.48

Health promotion through mHealth

According to the WHO, mobile and wireless technologies can potentially transform the face of health service delivery worldwide with the growing coverage of mobile cellular networks. mHealth programmes providing support to women in the reproductive health cycle using basic mobile devices are found in many countries; however, most programs remain informal and small in size or do not move beyond the pilot stage.49 This trend of failing to reach scale or institutionalization could be ascribed to the lack of pilot projects’ extensibility, interoperability and integration with the public health system50 and to an overemphasis on technical accomplishments instead of demonstrating impact on program or health outcomes. However, digital health strategies have potential as health-systems strengthening tools while working towards the achievement of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). A promising intervention to drive demand for services in low- and middle-income countries is targeted client communications through mobile phones (e.g. text messages).51

MomConnect is a flagship mHealth initiative coordinated by the South African National Department of Health aimed at strengthening the quality of maternal and infant health services and improving maternal and infant mortality outcomes at an accelerated pace. This text-based platform was launched in 2014 and its functions are accessible even through the most basic mobile phone. It is one of very few government-supported digital health initiatives enabled by high-level government buy-in and leadership that have been scaled up nationally and that are universally accessible. Within 3 years of its inception MomConnect reached 95% of public health facilities and 63% coverage of all women at their first antenatal visit, with 1.5 million subscribers. Very high mobile penetration rates in South Africa facilitated the roll out and acceptance of the program.50,51,52

Pregnant women register voluntarily into the free service of MomConnect at any public healthcare facility in South Africa at their first antenatal visit. The ultimate goal is the universal registration of all pregnant women in South Africa. Women receive targeted text messages with vital health information twice per week in the language of their choice. Content is tailored according to gestational age in pregnancy or the postpartum stage (until the child is 1 year old). During pregnancy women are encouraged to attend antenatal care and receive messages on diet, alcohol use, danger signs, fetal development and preparation for birth. After childbirth the focus shifts to reminders of postnatal visits, essential newborn care, nutrition and infant feeding (including exclusive breastfeeding), immunizations, hygiene and child development. The design of the MomConnect messages was informed by the program of the South African Mobile Alliance for Maternal Action. A further functionality of MomConnect is an interactive helpdesk for seeking information or giving user feedback on services received (Table 4).51,52,53

4

Lessons from MomConnect.

Writing evidence-based messages at a level that women can understand is possible |

MomConnect users are positive about the content of the messages and the delivery medium |

The investment in MomConnect as a digital solution contributed to the development of an interoperable digital national health information system |

Much more needs to be done to monitor the user journey54 and collect evidence that demonstrates the effect of MomConnect on maternal, newborn and child health outcomes |

For long-term sustainability, long-term commitment and earmarked funding for the maintenance of the core functions and innovation are required |

Postnatal breastfeeding support groups

Breastfeeding support groups gained high visibility when it was included as the 10th step of the Baby-friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI). The original wording was: “Foster the establishment of breastfeeding support groups and refer mothers to them on discharge from the hospital or clinic.” In 2018 this was changed in the revised BFHI implementation guidance to: “Coordinate discharge so that parents and their infants have timely access to ongoing support and care.” This places a stronger emphasis on HP and implies a closer working relationship between health facility and community to continue to care for a woman in the postnatal period and beyond and for the community to be actively involved in providing breastfeeding support services.28 One of these services would be the organization of breastfeeding support groups, which is the focus of this section.

Support is such a wide concept and is understood in different ways, including support that is supplementary to the standard care expected in a specific context. New mothers often have more than one source of support, one of which could be a breastfeeding support group. Support could be in the form of a telephone or online helpline with the birthing facility or a breastfeeding organization. The internet and social media are widely used as a source of breastfeeding information support where there is high mobile network coverage. MomConnect also provides breastfeeding messages. In communities where extended families still exist, relatives are an important source of support in terms of information, breastfeeding techniques and general helping out with the baby – sometimes leading to conflicting health messages from health care providers and the mother-in-law or other relatives. The complexity of health and social systems explains the difficulty to isolate the effect of one type of support – breastfeeding support groups per se – on outcomes such as exclusive breastfeeding, any breastfeeding, duration of breastfeeding, or the introduction of solid foods. Many studies combine different sources of support when measuring outcomes (e.g. different settings, types of support/interventions, timing of support, number of contacts). One source of social and informational support could be some kind of group support in the form of group counseling, mothers’ group meetings, mother-to-mother support, face‐to‐face support, volunteer support or community-based peer support.55,56,57 A specific schedule of four to eight contacts also appears to contribute to breastfeeding success.56

Conclusions of breastfeeding support studies are similar to a conclusion from a systematic review and meta-analysis by Sinha and colleagues: “To promote breastfeeding, interventions [including breastfeeding support groups] should be delivered in a combination of settings by involving health systems, home and family and the community environment concurrently”.55 The combination of role players from these settings will depend on the context. In their systematic review on interventions to promote exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months, Kim et al. found that effects were greater for professional-led interventions than for peer-led interventions. However, they argue that the lower-cost peer-support interventions (which could include breastfeeding support groups) may be more realistic in low-resource settings and low-income countries.58

In the past breastfeeding support groups were mostly run outside the public health system and relied on volunteers, such as those belonging to La Leche League or a local breastfeeding organization. Currently support groups are also organized by health care providers in the primary health care sector. Facilitators for the group sessions could include providers, trained mothers (lay volunteers) or a combination of both. In high-income countries mother may pay for attending these groups and can sometimes claim from medical insurance. One example of this kind of support is the Baby Café services in the United Kingdom and the United States, some of which also provide breastfeeding support groups.59,60,61 Other group support services reported in the literature are the Bosom Buddy Project that encourages culturally sensitive breastfeeding support62 and the Group of Empowered Mothers (GEMs) for mothers with critically ill hospitalized infants.63 Finally there are also peer support groups for specific subgroups where breastfeeding is an important topic in activities. One example is the mothers2mothers organization that started in South Africa to support HIV positive women and which is now active in a number of African countries.64

Looking at CentringPregnancy®, MomConnect and breastfeeding support groups, which of the principles contained in each of these interventions have you used in the context where you work? What ideas did you get from these interventions to use in your own practice?

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We would like to thank Bob Pattinson, Sarie Oosthuizen and Martin Bac for their constructive inputs in the planning and the first draft of the chapter.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- Health promotion and health education programs and activities should be based on content and interventions for which there is a sound evidence base.

- When interacting with women and their families in groups or individually:

- Use adult education principles;

- Use a person-centered approach;

- Avoid downloading information in jargon that cannot be understood;

- Repeat important messages on more than one occasion;

- Ask the client to explain back to you what you have said to ensure that she understood.

- If you plan a new health promotion or health education intervention do a needs assessment.

- Where possible, link it with research to contribute to the evidence base of what constitutes a successful intervention.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Author(s) statement awaited.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

REFERENCES

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Quick Guide to Health Literacy, 2008. Available at: https://health.gov/communication/literacy/quickguide/Quickguide.pdf (Accessed 19 January 2019). | |

World Health Organization. Meeting to Develop a Global Consensus on Preconception Care to Reduce Maternal and Childhood Mortality and Morbidity. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2013. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/78067/9789241505000_eng.pdf;jsessionid=ED8D4FA937520F505D9CBB71428FE701?sequence=1 (Accessed 15 January 2019). | |

World Health Organization. Health Promotion 2019. Available at: https://www.who.int/topics/health_promotion/en/ (Accessed 19 January 2019) | |

World Health Organization. Health Education 2019. Available at: https://www.who.int/topics/health_education/en/ (Accessed 19 January 2019) | |

World Health Organization. What is Health Promotion? 2016. Available at: https://www.who.int/features/qa/health-promotion/en/ (Accessed 19 January 2019) | |

World Health Organization, Europe. Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion 1986. Available at: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/129532/Ottawa_Charter.pdf (Accessed 13 January 2019) | |

World Health Organization. Primary Health Care 2019. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/primary-health-care (Accessed 20 June 2019). | |

Pender N. Health Promotion Model Manual. Michigan: University of Michigan, Deep Blue, 2011. Available at: https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/handle/2027.42/85350/HEALTH_PROMOTION_MANUAL_Rev_5–2011.pdf (Accessed 19 January 2019). | |

Nielsen-Bohlman L, Panzer AM, Kindig DA, Committee on Health Literacy (eds.) Heath Literacy: a Prescription to End Confusion. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press, 2004. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK216032/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK216032.pdf (Accessed 26 December 2018). | |

Cowan CF. Teaching patients with low literacy skills. In: Lowenstein AJ, Bradshaw MJ, (eds.) Fuszard's Innovative Teaching Strategies in Nursing. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett, 2004. p. 278–85. | |

Intervention MICA. What is an Intervention? Available at: https://health.mo.gov/data/interventionmica/index_4.htmls (Accessed 19 January 2019). | |

Dr Natasha K. Health promotion and health education. Lecture 2. Introduction to health education. Available at: https://www.slideshare.net/drnatasha2/introduction-to-healtheducation-and-health-promotion-part-2 (Accessed 12 December 2018). | |

Mwaniki M, Baya E, Mwangi-Powell F, et al. ‘Tweaking’ the model for understanding and preventing maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality in low income countries: “inserting new ideas into a timeless wine skin”. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016;16:14. | |

World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2016. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/250796/9789241549912-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (Accessed 15 January 2019). | |

World Health Organization. Fact sheet. Available at: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/ (Accessed 15 January 2019). | |

World Health Organization. Regional Office for South-East Asia. A Brief Guide to Emerging Infectious Diseases and Zoonoses. New Delhi: World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia, 2014. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/204722/B5123.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (Accessed 15 January 2019). | |

Evans EC. A review of cultural influence on maternal mortality in the developing world. Midwifery 2013;29(5):490–6. | |

Puppo V. Female genital mutilation and cutting: An anatomical review and alternative rites. Clin Anat 2017;30(1):81–8. | |

World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations: Intrapartum Care for a Positive Childbirth Experience. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2018. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/260178/9789241550215-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (Accessed 15 January 2019). | |

World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience: Summary. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2018. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259947/WHO-RHR-18.02eng.pdf;jsessionid=8CE7D2646C2DC5CEDE88363CFD7CCABB?sequence=1 (Accessed 15 January 2019). Contract No.: Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. | |

The Lancet. Stillbirths 2011. Lancet 2011;377(9774). | |

The Lancet. Stillbirths 2016: Ending preventable stillbirths. Lancet 2016;387(10018). | |

The Lancet. Every Newborn. Lancet 2014;384(9938). | |

Tommy's. I'm pregnant. https://www.tommys.org/pregnancy-information/im-pregnant (Accessed 30 June 2019). | |

Best beginnings. Baby buddy app. https://www.bestbeginnings.org.uk/baby-buddy (Accessed 30 June 2019). | |

Norman JE, Heazell AEP, Rodriguez A, et al. Awareness of fetal movements and care package to reduce fetal mortality (AFFIRM): a stepped wedge, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet 2018;392(10158):1629–38. | |

World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations on Postnatal Care of the Mother and Newborn. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2013. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/97603/9789241506649_eng.pdf?sequence=1 (Accessed 15 January 2019). | |

World Health Organization. Protecting, promoting and supporting breastfeeding in facilities providing maternity and newborn services – the revised Baby-friedly Hospital Initiative. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272943/9789241513807-eng.pdf?ua=1 (Accessed 26 January 2019). | |

Bryanton J, Beck C, Montelpare W. Postnatalparental education for optimizing infant general health and parent-infant relationships. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013(11):CD004068. | |

Intervention. Available at: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/intervention (Accessed 21 January 2019). | |

Infosihat. Health Promotion: Methods and Approaches. Putrajaya, Malaysia: Health Education Division, Ministry of Health Malaysia. Available at: http://www.infosihat.gov.my/images/Bahan_Rujukan/He_Perancangan/Method_and_Approaches_in_HP.pdf (Accesssed 26 December 2018). | |

World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations on Health Promotion Interventions for Maternal and Newborn Health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/172427/9789241508742_report_eng.pdf;jsessionid=D8D11EBBC52C015E52A14D2BCF692BC4?sequence=1 (Accessed 19 January 2019). | |

Global Health Media. Videos – English. Available at: https://globalhealthmedia.org/videos/ (Accessed 25 January 2019). | |

Open Learn Create. Health Education, Advocacy and Community Mobilisation. Module 10. How to Teach Health Education and Health Promotion. Available at: http://www.open.edu/openlearncreate/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=167 (Accessed 15 January 2019). | |

Lieb S. Principles of Adult Learning. Phoenix, AZ: South Mountain Community College; 1991. Available at: https://petsalliance.org/sites/petsalliance.org/files/Lieb%201991%20Adult%20Learning%20Principles.pdf (Accessed 25 January 2019). | |

Byerley BM, Haas DM. A systematic overview of the literature regarding group prenatal care for high-risk pregnant women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017;17(1):329. | |

Rotundo G. Centering pregnancy: the benefits of group prenatal care. Nursing Women's Health 2011;15(6):508–17. | |

Strickland C, Merrell S, Kirk JK. CenteringPregnancy: Meeting the quadruple aim in prenatal care. NC Med J 2016;77(6):394–7. | |

Conde C. Center of attention: new pregnancy program improves prenatal care. Tex Med 2010;106(10):45–50. | |

Rising S. Centering pregnancy. An interdisciplinary model of empowerment. J Nurse Midwifery 1998;43(1):46–54. | |

Schellinger MM, Abernathy MP, Amerman B, et al. Improved outcomes for Hispanic women with gestational diabetes using the Centering Pregnancy© Group Prenatal Care Model. Matern Child Health J 2017;21(2):297–305. | |

Eluwa GI, Adebajo SB, Torpey K, et al. The effects of centering pregnancy on maternal and fetal outcomes in northern Nigeria; a prospective cohort analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018;18(1):158. | |

Patil CL, Abrams ET, Klima C, et al. CenteringPregnancy-Africa: a pilot of group antenatal care to address Millennium Development Goals. Midwifery 2013;29(10):1190–8. | |

Kania-Richmond A, Hetherington E, McNeil D, et al. The impact of introducing Centering Pregnancy in a community health setting: a qualitative study of experiences and perspectives of health center clinical and support staff. Matern Child Health J 2017;21(6):1327–35. | |

Klima C, Norr K, Vonderheid S, et al. Introduction of CenteringPregnancy in a public health clinic. J Midwifery Womens Health 2009;54(1):27–34. | |

Novick G, Sadler LS, Knafl KA, et al. In a hard spot: providing group prenatal care in two urban clinics. Midwifery 2013;29(6):690–7. | |

Novick G, Womack JA, Lewis J, et al. Perceptions of barriers and facilitators during implementation of a complex model of group prenatal care in six urban sites. Res Nurs Health 2015;38(6):462–74. | |

Xaverius PK, Grady MA. Centering pregnancy in Missouri: a system level analysis. ScientificWorldJournal 2014;2014:285386. | |

World Health Organization. mHealth: New Horizons for Health through Mobile Technologies. Global Observatory for eHealth series – Volume 3. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2011. Available at: https://www.who.int/goe/publications/goe_mhealth_web.pdf (Accessed 26 January 2019). | |

Seebregts C, Dane P, Parsons AN, et al. Designing for scale: optimising the health information system architecture for mobile maternal health messaging in South Africa (MomConnect). BMJ Glob Health 2018;3(Suppl 2):e000563. | |

Mehl GL, Tamrat T, Bhardwaj S, et al. Digital health vision: could MomConnect provide a pragmatic starting point for achieving universal health coverage in South Africa and elsewhere? BMJ Glob Health 2018;3(Suppl 2):e000626. | |

Barron P, Peter J, LeFevre AE, et al. Mobile health messaging service and helpdesk for South African mothers (MomConnect): history, successes and challenges. BMJ Glob Health 2018;3(Suppl 2):e000559. | |

Skinner D, Delobelle P, Pappin M, et al. User assessments and the use of information from MomConnect, a mobile phone text-based information service, by pregnant women and new mothers in South Africa. BMJ Glob Health 2018;3(Suppl 2):e000561. | |

Peter J, Benjamin P, LeFevre AE, et al. Taking digital health innovation to scale in South Africa: ten lessons from MomConnect. BMJ Glob Health 2018;3(Suppl 2):e000592. | |

Sinha B, Chowdhury R, Sankar MJ, et al. Interventions to improve breastfeeding outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr 2015;104(467):114–34. | |

McFadden A, Gavine A, Renfrew MJ, et al. Support for healthy breastfeeding mothers with healthy term babies. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017(2):Cd001141. | |

Shakya P, Kunieda MK, Koyama M, et al. Effectiveness of community-based peer support for mothers to improve their breastfeeding practices: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One 2017;12(5):e0177434. | |

Kim S, Park S, Oh J, et al. Interventions promoting exclusive breastfeeding up to six months after birth: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Nurs Stud 2018;80:94–105. | |

Fox R, McMullen S, Newburn M. UK women's experiences of breastfeeding and additional breastfeeding support: a qualitative study of Baby Cafe services. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015;15:147. | |

Gregg DJ, Dennison BA, Restina K. Breastfeeding-friendly Erie County: establishing a Baby Cafe network. J Hum Lact 2015;31(4):592–4. | |

Delgado RI, Gill SL. A microcosting study of establishing a Baby Café in Texas. J Hum Lact 2018;34(1):77–83. | |

Friesen CA, Hormuth LJ, Curtis TJ. The Bosom Buddy Project: a breastfeeding support group sponsored by the Indiana Black Breastfeeding Coalition for Black and Minority Women in Indiana. J Hum Lact 2015;31(4):587–91. | |

Kristoff KC, Wessner R, Spatz DL. The birth of the GEMs group: implementation of breastfeeding peer support in a children's hospital. Adv Neonat Care 2014;14(4):274–80. | |

mothers2mothers. What we do and why. https://www.m2m.org/what-we-do-and-why/ (Accessed 27 January 2019). |