This chapter should be cited as follows:

Giacomozzi M, Nap A, Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.417673

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Gynecology Module

Volume 3

Endometriosis

Volume Editors:

Professor Andrew Horne, University of Edinburgh, UK

Dr Lucy Whitaker, University of Edinburgh, UK

Chapter

Surgical Management of Endometriosis-associated Pain

First published: September 2022

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

Endometriosis is characterized by chronic pelvic pain.1 Cyclic and noncyclic pelvic pain can be experienced during menstruation (dysmenorrhea), penetrative sex (dyspareunia), urination (dysuria), and/or defecation (dyschezia).2 The chronic nature of endometriosis-associated pain greatly affects the quality of life of people living with this condition.1,3,4 Endometriosis compromises patients’ professional ambitions, social interactions, intimate relationships, and family planning.5 The psychological, social, and economic consequences of endometriosis are multidimensional and can be life-long.2,5 Therefore, adequate pain management is crucial to improve patients’ quality of life and the fulfillment of their personal goals.

The chronic features characterizing endometriosis require long-term management strategies in which surgical procedures are often preceded and/or followed by analgesic and hormonal therapies as described in Chapter 4. Before now, surgical management was seen as an alternative to medical treatments, whereas recently the consensus has shifted to a combined approach.6 Pharmacological therapies are increasingly prescribed in preparation for surgical interventions to reduce endometriosis lesion volumes and facilitate minimally invasive approaches. Postoperative hormonal suppression is often advised to patients who are not trying to conceive to prevent recurrences, alongside long-term analgesic treatments. It is thus important to understand that medical and surgical endometriosis-associated pain-management strategies are complementary rather than substitutive.

Laparoscopies are the current gold standard in endometriosis surgical treatment.7 However, historically, large laparotomies prevailed.8,9 Open surgeries often employed invasive methods that regularly included hysterectomies at a young age and large bowel surgeries. This type of surgery entailed a high risk of complications and long hospitalization periods. The evolution of surgical techniques and rapid progress in laparoscopic imaging quality facilitated a shift towards more conservative and less invasive procedures.7 Over the years, laparoscopic techniques took over to minimize surgery-associated risks and costs as in many other surgical treatments.10 More recently, the arrival of robot-assisted surgery opened new possibilities in the management of endometriosis, which are rapidly progressing.11 Additionally, the advancement in surgical techniques has been accompanied by an increase in expertise and the consolidation of skills of endometriosis surgeons worldwide that enabled a consistent improvement in patients’ treatment options.7 Newer techniques made endometriosis surgical management accessible for those patients that were otherwise ineligible for laparotomies. They present the advantages of quicker recoveries, shorter hospital stays, and better cosmetic results, although their effect on fertility and enhancement of conception chances remains under investigation. This chapter provides an overview of the surgical procedures currently in use to manage endometriosis-associated pain based on the location of the endometriosis lesions.

SHARED DECISION-MAKING AND PATIENT SELECTION

Surgery offers treatment options for patients who are resistant to pharmacological approach and/or for whom hormonal therapies are contraindicated due to risk of complication, comorbidities, or when actively trying to conceive.4

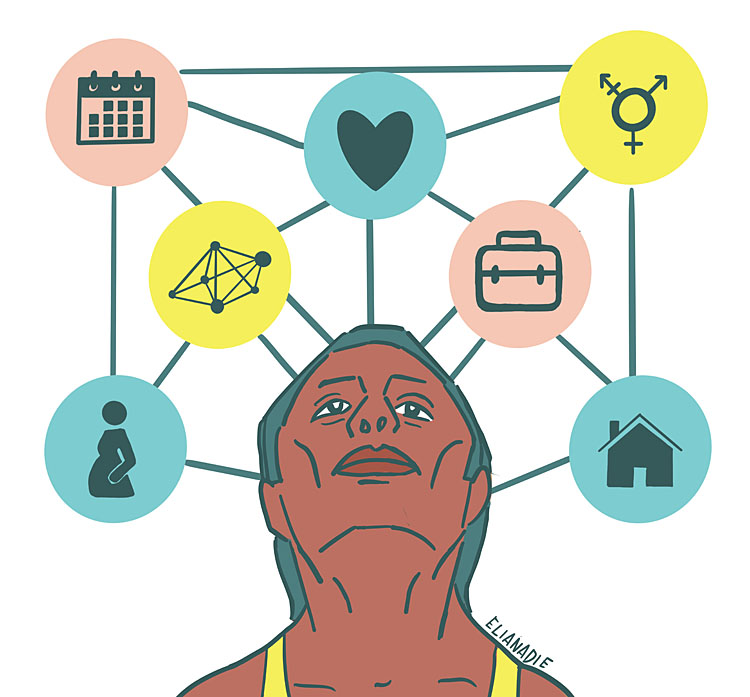

Personal and disease characteristics interplay in the considerations for a surgical approach (Figure 1). A shared decision-making process is critical for the successful treatment of endometriosis-associated pain.12,13,14,15,16 Thus, each patient’s personal goals need to be explored to tailor the most appropriate treatment for them. The extent to which social and professional life are compromised gives an estimation of the desirability and urgency of the surgery. Different surgical options are discussed depending on someone’s symptoms, age, reproductive wish, gender perception, intimate relationships, peer-support network, and professional profile. At the same time, the degree and location of endometriosis lesions help in estimating the chances of successful surgical endometriosis-associated pain management.17 While a comprehensive predictive model is presently under development, several prognostic factors have already been identified.18 Patients benefiting the most from surgical treatment have higher preoperative pain scores, advanced disease stages (ASRM III and IV), and deep endometriosis (DE). On the other hand, lower preoperative pain scores, early disease stages, and superficial peritoneal endometriosis are associated with less successful surgical outcomes.19,20 In addition, physical comorbidities such as obesity, irritable bowel syndrome, and fibromyalgia are common in patients with endometriosis.21,22 These conditions can increase the chances of perioperative complications and negatively affect the residual postoperative pain. Given that the preoperative symptoms are often multifactorial, the sole removal of endometriosis lesions cannot be expected to improve all complaints. Thus, patients living with comorbidities that involve pelvic pain may expect less successful results from endometriosis surgery alone. In addition, patients’ mental resilience and attitudes are key to understand pain perception and, by extension, pain reduction, especially given the high rate of psychological comorbidities among people with endometriosis and the heavy mental burden of endometriosis itself.23,24,25 Consequently, adequate expectation management regarding surgical options and outcomes is essential in the shared decision-making process to improve endometriosis-associated pain.

1

Factors interplaying in the shared decision-making process. Reproduced with permission from Elia Nadie.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT BASED ON ENDOMETRIOSIS LOCATION

The following paragraphs will discuss the most common and up-to-date surgical procedures to manage endometriosis-associated pain based on the location of endometriosis lesions. It is important to consider that endometriosis can be present at multiple locations concomitantly, and that it may or may not be desirable to remove all lesions during the same surgery, depending on a variety of individual patient-related factors. Case-to-case considerations are therefore crucial in the shared decision-making process leading to the surgical procedure.

Superficial Peritoneal Endometriosis

Superficial peritoneal endometriosis (SE) is the most prevalent form of endometriosis, accounting for 80% of the cases.26 SE can be present separately, or it can co-exist with other forms of endometriosis including adenomyosis and ovarian and deep endometriosis.26 There is disagreement among the scientific community regarding whether SE is a unique condition or a different form of the same condition as other endometriosis types, as SE itself is heterogeneous in its presentation.26,27 Peritoneal endometriotic lesions vary in extent, physical appearance at laparoscopy, and location, which make SE surgical management particularly challenging.26,28 Isolated SE is associated with gynecological symptoms typical of endometriosis; these include moderate to severe dysmenorrhea and deep dyspareunia.28 SE is further independently associated with primary subfertility.28

There are currently no published randomized controlled trials that have investigated the role of surgery for isolated SE pain-related management.27 The frequent co-presence of SE and other endometriosis types often confounds research results. At the same time, studies that select patients based on ASRM I and II classification cannot be generalized to people with SE only.27 Further studies investigating the role of surgery for isolated SE are necessary to establish the benefits and risks of such procedures.

Ablation versus excision of endometriotic lesions

Common surgical techniques for removal of endometriotic lesions include ablation and excision. Both provide good pain relief and overall symptoms reduction.29,30 Some authors suggested that ablation has the potential disadvantage of leaving more necrotic tissue behind, which may imply an elevated risk of inflammation and fibrosis, while excision may facilitate a more rapid regrowth of the peritoneum at the site of incision.31

Nevertheless, review studies show no differences in pain reduction between excision and ablation in the first postoperative year.29,31,32,33 Meta-analysis results reveal no difference in dysmenorrhea, dyschezia or dyspareunia for patients who had endometriosis removed by excision versus ablation.29 Pain scores were measured with the visual analog scale (VAS), in ordinal rank or with EHP-30 pain scores.29 Excision and ablation showed similar effectiveness for the treatment of endometriosis-associated pain one year after surgery.31,32,33 Endometriosis recurrence rate was also similar. Studies with more extensive follow-up periods remain necessary for assessing pain outcomes in the long-term and establishing superiority or similarity between the two techniques.

Surgery for ovarian endometrioma

Cystectomy (removal of the cyst) is the most frequently performed surgery for removal of ovarian endometrioma.27 Oophorectomy (removal of the ovary) offers an efficient and definitive treatment alternative.34 However, oophorectomy in premenopausal patients is related to reduction of their reproductive potential, meaning here decreased ovarian reserve and ovarian mass, premature ovarian insufficiency (POI), and early menopause onset.35,36 Long-term consequences of premature menopause include lower bone density, higher chances of osteoporosis, and elevated cardiovascular risk profile.35 Consequently, bilateral oophorectomy is considered only under strict circumstances, namely when the patient has fulfilled their reproductive wishes.34 Unilateral oophorectomy is usually preferred over a bilateral approach.35,36

Laparoscopic cystectomy is overall considered a safe procedure with low complications risk; however, care has to be taken in patients with reproductive wishes to protect the ovarian reserve as much as possible. Different techniques are employed to surgically manage endometrioma without removing the ovary. Excision, drainage, and coagulation by bipolar diathermy, and CO2 laser vaporization are currently performed depending on the availability of surgical devices and on the experience of the individual surgeon. Few studies compared these techniques assessing postoperative endometriosis-associated pain and endometrioma recurrence rate.

Hart et al. reviewed the role of cyst excision compared to drainage and coagulation. Patients with no previous endometriosis surgery and endometrioma greater than 3 cm had better outcomes with excision techniques.37,38,39,40 Both excision and drainage and coagulation showed significant pain reduction in the short-term follow-up. Excision additionally proved to benefit dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and non-cyclic pain in the longer follow-up periods (up to 26 months).37 Secondary outcomes, namely endometrioma recurrence rate, were also better with excision techniques compared to drainage and coagulation.37

A randomized controlled trial and a retrospective study compared cystectomy with laser vaporization, and in both, endometriosis-related pain 2 years after surgery was slightly higher in patients who underwent laser vaporization of the cyst.41,42 However, earlier cyst recurrence and a higher recurrence rate were reported in the laser group.41 The difference in recurrence was statistically significant 12 months after surgery, but not in the 5-year follow-up.41

In conclusion, evidence suggests that endometrioma excision provides better pain outcomes and lower recurrence rates compared to drainage and coagulation.27,37 Cystectomy and CO2 laser vaporization have shown comparable results in the first year after surgery.27 However, shorter postoperative recurrence rates are lower for cystectomy, thus proving the superiority of excision techniques for management of ovarian endometrioma.27

Consideration for ovarian reserve following endometrioma surgery

Surgery for endometrioma can damage the patient’s ovarian reserve and induce premature ovarian failure.27,43 Cystectomy can compromise both ovarian volume and antral follicle count (AFC).27 Repeated surgery for recurrent endometrioma implies an elevated risk compared to first surgery.44 Likewise, a bilateral approach has shown a stronger detrimental effect on ovarian reserve and functionality than unilateral cystectomy.45 Intraoperative damage control is thus imperative to preserve patients’ reproductive potential and prevent long-term effects of premature ovarian failure.

Surgery for deep endometriosis

Deep endometriosis (DE) is defined as endometriosis lesions affecting different anatomical areas >- 5 mm beneath the peritoneum.27 These include the posterior department (i.e., uterosacral ligaments, vagina, rectovaginal septum, bladder, and ureters), pelvic side walls, and/or gastrointestinal tract.27 When the latter is compromised, the term “bowel endometriosis” is used.46 As surgical management of DE, excision of endometriosis nodules is usually performed.27 Extensive literature has documented significant pain reduction and improved Quality of Life (QoL) scores in the 2 years following DE surgery.47,48,49,50

A systematic review that included laparoscopic, laparotomic, transvaginal, and combined approaches for DE surgery, showed successful results in pain scores and improvement of gastrointestinal symptoms.48 Complication rate was 0–3% and recurrence rate 5–25%.48 A large multicenter prospective study consolidated these findings and reported reduced analgesia use and improved QoL.50 The complication rate was 6.8%, with 1.1% affecting the gastrointestinal tract (enterotomy, anastomotic leak, or fistula) and 1.0% the urinary tract (ureteric or bladder injury or leak).50 Quality of life changes after DE surgery have been largely investigated. Regardless of the type of QoL measurement tool used, significant improvements have been reported in the majority of or all domains.47,50

In summary, DE surgery may appreciably improve QoL and endometriosis-associated pain during a certain period. However, this should be carefully weighed against the significant risk of complications and the challenges related to the diverse surgical approaches, techniques, and outcome measurements.27 Therefore, such surgeries are generally performed in a center of expertise with a highly experienced team.

Surgery for posterior compartment endometriosis

Deep endometriosis can be present in the posterior compartment, including in the uterosacral ligaments, vagina, rectovaginal septum, bladder, and ureters. The presence of endometriosis in more than one of these locations is common. For instance, ureteral and bladder endometriosis are concomitant in 19.8% of the cases.51 Although high-level evidence is lacking, improvement in pain symptoms and QoL scores have been reported after excision of endometriosis lesions in such locations.52,53 Overall, the more lesions tackled during one surgery, the higher the chances of significant pain reduction after treatment.27 For example, upon resection of endometriosis in the rectovaginal pouch, a concomitant hysterectomy can offer additional pain relief.54 Hence, the importance of a comprehensive surgical approach should be pondered against the risks of complications with the objective of maximizing pain reduction and minimizing recurrence, and thus the need for reoperation.27

Endometriosis in the uterosacral ligaments and vagina can be detected during pelvic examination.27 This type of endometriosis has been associated with chronic pelvic pain, deep dyspareunia, and poor sexual function. Surgical treatment has proven to reduce pain symptoms and improve deep dyspareunia, quality of sex life, and sexual function, particularly in the case of the excision of endometriosis lesions on the uterosacral ligaments.50,55 Major complications are uncommon for uterosacral and vaginal endometriosis surgery, while minor complications encompass superficial vascular injuries and ureteral stenosis.53

Bladder endometriosis is surgically treated with the excision of the lesion and subsequent closure of the bladder wall.27 Partial cystectomy and shaving are techniques that offer low complication and recurrence rates for the management of bladder endometriosis.56,57,58,59,60 Ureteral endometriosis lesions can be excised after stenting the ureter in milder cases, while a segmental excision with an end-to-end anastomosis or reimplantation of the ureter is used for more advanced disease stages.27 Ureterolysis offers a conservative approach that is suitable for most patients with ureteral endometriosis. However, ureteral resection, re-anastomosis, and ureteroneostomy are also performed when ureterolysis is not sufficient. Major complications occur in 3.2% of the cases and reoperation in 3.9%, thus suggesting the need for careful pre- and intraoperative considerations and the joint involvement of experienced urologists and gynecologists for the management of these types of endometrioses.51

Surgery for bowel endometriosis

Gastrointestinal involvement of DE is present in 5–12% of endometriosis patients.61 The sigmoid colon and rectum are the most frequently affected organs by this form of endometriosis.27 In the case of bowel endometriosis, gastrointestinal (cyclic) symptoms are common. These can consist of dyschezia, constipation, diarrhea, and rectal bleeding, and they may vary based on the location and extent of the endometriosis lesions.62

The literature extensively addresses the benefits of DE bowel surgery to improve pain symptoms and quality of life.27 As for other types of endometrioses, laparoscopy is preferred to laparotomy as a surgical intervention in cases of bowel endometriosis since it offers quicker recovery times, shorter hospital stays, and better cosmetic results.27,63

The techniques used for the surgical management of bowel endometriosis remain possibly the most controversial topic within the field of endometriosis surgery. Shaving, discoid excision, and segmental resection are the three most common techniques. Historically, DE bowel surgery has shifted towards a more conservative approach whereby segmental resection has slowly receded in favor of shaving and discoid excision. However, some scholars still argue that more aggressive methods are necessary for managing severe symptoms and preventing reoperation, especially in younger patients. The recurrence rate for colorectal endometriosis is, in fact, between 5% and 25% in the 2-year follow-up period.48 At the same time, a significant complication rate for DE surgery, as high as 2.1% intraoperative and 13.9% postoperative, calls for less invasive approaches.64

Shaving, discoid excision, and segmental resection have all been proven to significantly improve DE symptoms.27 However, the superiority of one technique above the others is highly disputed.27 The ongoing debate is challenged by the difficulty of selecting and randomizing homogenous patient cohorts. Existing evidence suggests that the location, dimension, and extent of endometriosis lesions should all be taken into account while opting for one surgical technique instead of another. For higher lesions of the sigmoid, segmental resections show more successful results.27,65 For lower lesions in the rectum, conservative techniques (i.e., shaving and discoid excision) may be chosen for smaller noduli (less than 2 cm).27,66 Management of bigger lesions in the rectum continues to be controversial.27 Tailored care and case-by-case considerations remain crucial in this process. Patients' personal goals and preferences can be explored through the shared decision-making process mentioned throughout this chapter. Key factors herein are the comparison of the patient’s age, reproductive wishes, severity of the symptoms, comorbidities, and acceptability of complications (including stoma risk), versus the chance of recurrence. In any case, the involvement of a gastrointestinal surgeon and close multidisciplinary collaboration should enable the best care possible for patients with bowel endometriosis, which is usually treated only in highly specialized centers.

Hysterectomy

Despite patients often presenting with a firm wish for hysterectomy, strong high-quality evidence showing significant pain reduction after such surgery is lacking, posing constantly evolving ethical and medical dilemmas for endometriosis surgeons.27 Chance of residual pain and risk of reoperation should be discussed conscientiously given the scarcity of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and systematic reviews investigating the effect of hysterectomy for endometriosis specifically. Patients’ age and reproductive wishes are central in the shared decision-making process leading to the procedure.

A Swedish population-based registry study reports a significant, long-lasting reduction in pain symptoms after hysterectomy among people with endometriosis.67 These results consolidate the findings of another retrospective study that examined the risk of reoperation following hysterectomy for a 7-year follow-up period.68 The findings of these two retrospective studies suggest that hysterectomy combined with the removal of other endometriosis lesions improve pain symptoms and decrease reoperation risk in the long-term.67,68,69 The accurate and comprehensive surgical removal of other superficial and deep lesions is thus a predictive factor for a successful pain reduction after hysterectomy.69 Further studies differentiating preoperative symptoms (e.g., cyclic versus non-cyclic pain) and patient characteristics are needed to better evaluate and predict response to surgical treatment.69

Upon hysterectomy, bilateral oophorectomy could also be considered, weighing the risks of endometriosis recurrence against the consequences of early menopause and hormone therapy supplementation.27 Older studies (pre-2000s) showed a sixfold risk of recurrent pain and an eightfold risk of reoperation in the case of hysterectomy alone compared to hysterectomy with bilateral oophorectomy.70 These results should, however, be considered critically given the substantial developments in endometriosis surgical techniques and postoperative hormone regimes that have occurred in the last decade. Ongoing studies are examining the implications of performing a bilateral salpingectomy at the time of hysterectomy suggesting a potential benefit to decrease the risk of ovarian carcinoma later in life.

In the case of hysterectomy, a total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) is preferred to minimize the risk of persistent endometriosis in the cervix and adjacent tissue compared to supracervical hysterectomy.

GLOBAL HEALTH ASPECTS OF ENDOMETRIOSIS SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Millions of people live with endometriosis worldwide; its global burden is considered severe.71,72,73 Availability and accessibility of surgical treatment options vary among different settings.74,75 Yet, epidemiological global data on endometriosis is lacking.72 Higher incidence and prevalence are reported in high-income countries, while they remain unclear in low- and middle-income countries.72

The lack of awareness, insufficient personnel training, and inadequate health infrastructure seriously compromises endometriosis care on a global scale.76 Resource restrictions affect both the diagnostic and treatment process.75,76 Given prolonged diagnostic delays, it can be assumed that distribution and frequency of endometriosis have been underestimated in the last decades, especially for low- and middle-income countries.72,76 The Covid-19 pandemic has further aggravated endometriosis-related global health disparities by disproportionately damaging accessibility to healthcare utilization.77 Elective endometriosis surgeries have been delayed and/or cancelled, while personnel trained to provide endometriosis care has been re-allocated to other health services. The psychological and economic stress resulting from the pandemic has added to the chronic pain and distress experienced by people living with endometriosis.77

In high-income countries a laparoscopic approach to endometriosis is often preferred, while in low- and middle-income countries laparoscopy remains hardly available.78 The costs of purchasing and maintaining up-to-date equipment constitute significant financial barriers. This adds to the difficulty of training specialized personnel.78,79 Compared to laparoscopic procedures, robot-assisted surgeries imply even more elevated costs and additional personnel training, which pose added challenges in their implementation – an issue also faced by high-income countries. Their employment across resource-limited settings would require a substantial structural strengthening of health systems' capacity.

In conclusion, surgical treatments are globally less accessible to those communities facing general difficulties in accessing healthcare services, such as people of color, indigenous groups, people living in rural areas, and those with a lower socioeconomic status.80,81,82 The gendered aspect of endometriosis further exacerbates widespread gender-based inequalities. Barriers to adequate surgical endometriosis care disproportionately affect those communities already disadvantaged by social and health inequalities. The removal of these barriers is necessary to assure adequate endometriosis care on a global scale.76

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- Patients' personal goals and preferences should be explored through a shared decision-making process. Patient-related factors to consider are symptoms, age, reproductive wish, gender perception, intimate relationships, peer-support network, and professional profile. Endometriosis-related factors include degree and location of endometriosis lesions, and recurrence status.

- Adequate expectation management regarding surgical options and outcomes, as well as case-to-case considerations are essential in the process leading to the surgical procedure.

- Surgical management of endometriosis-related pain can be complementary to medical and non-medical treatments.

- Surgical removal of endometriosis lesions and/or affected organs may improve pain and quality of life.

- Excision or ablation of superficial endometriosis lesions can both be performed depending on the availability of surgical devices and on the experience of the individual surgeon.

- Excision is the superior surgical technique for ovarian endometrioma to decrease pain and risk of recurrence.

- Oophorectomy can be considered in the case of recurrence of ovarian endometriosis, weighting against the risk of premature ovarian failure, and long-term hormonal supplementation.

- Surgical removal of deep endometriosis improves pain symptoms, quality of life, and sexual function during a certain period.

- Total laparoscopic hysterectomy is the preferred method for performing hysterectomy when the patient has concomitant endometriosis.

- Not all diagnostic and/or surgical procedures may be accessible across different settings. Consider the safest options for your patient also based on geographic location.

PERMISSIONS

Permission to reproduce illustrations has been granted by the illustrator Elia Nadie.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) of this chapter declare that they have no interests that conflict with the contents of the chapter.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

REFERENCES

van Aken MA, Oosterman JM, Van Rijn C, et al. Pain cognition versus pain intensity in patients with endometriosis: toward personalized treatment. Fertility and sterility 2017;108(4):679–86. | |

Della Corte L, Di Filippo C, Gabrielli O, et al. The burden of endometriosis on women’s lifespan: a narrative overview on quality of life and psychosocial wellbeing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020;17(13):4683. | |

Gao X, Outley J, Botteman M, et al. Economic burden of endometriosis. Fertility and Sterility 2006;86(6):1561–72. | |

Zondervan KT, Becker CM, Missmer SA. Endometriosis. New England Journal of Medicine 2020;382(13):1244–56. | |

Marinho MC, Magalhaes TF, Fernandes LFC, et al. Quality of life in women with endometriosis: an integrative review. Journal of Women's Health 2018;27(3):399–408. | |

Kalaitzopoulos DR, Samartzis N, Kolovos GN, et al. Treatment of endometriosis: a review with comparison of 8 guidelines. BMC Women's Health 2021;21(1):1–9. | |

Fleischer K, El Gohari A, Erritty M, et al.Excision of endometriosis–optimising surgical techniques. The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist 2021;23(4):310–7. | |

Busacca M, Fedele L, Bianchi S, et al. Surgical treatment of recurrent endometriosis: laparotomy versus laparoscopy. Human Reproduction 1998;13(8):2271–4. | |

Crosignani PG, Vercellini P, Biffignandi F, et al. Laparoscopy versus laparotomy in conservative surgical treatment for severe endometriosis. Fertility and Sterility 1996;66(5):706–11. | |

Luu TH, UY-KROH M. New developments in surgery for endometriosis and pelvic pain. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology 2017;60(2):245–51. | |

Gitas G, Hanker L, Rody A, et al. Robotic surgery in gynecology: is the future already here? Minimally Invasive Therapy & Allied Technologies 2022:1–10. | |

Metzemaekers J, Slotboom S, Sampat J, et al. Crossroad decisions in deep endometriosis treatment options: a qualitative study among patients. Fertility and Sterility 2021;115(3):702–14. | |

Metzemaekers J, van den Akker‐van Marle ME, Sampat J, et al. Treatment preferences for medication or surgery in patients with deep endometriosis and bowel involvement–a discrete choice experiment. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 2021. | |

Elwyn G, Edwards A, Wensing M, et al. Shared decision making: developing the OPTION scale for measuring patient involvement. Qual Saf Health Care 2003;12(2):93–9. | |

Stiggelbout AM, Pieterse AH, De Haes JC. Shared decision making: Concepts, evidence, and practice. Patient Educ Couns 2015;98(10):1172–9. | |

Vercellini P, Buggio L, Frattaruolo MP, et al. Medical treatment of endometriosis-related pain. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2018;51:68–91. | |

Chopin N, Vieira M, Borghese B, et al. Operative management of deeply infiltrating endometriosis: results on pelvic pain symptoms according to a surgical classification. Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology 2005;12(2):106–12. | |

Marlin N, Rivas C, Allotey J, et al. Development and Validation of Clinical Prediction Models for Surgical Success in Patients With Endometriosis: Protocol for a Mixed Methods Study. JMIR Research Protocols 2021;10(4):e20986. | |

Abbott J, Hawe J, Clayton R, et al. The effects and effectiveness of laparoscopic excision of endometriosis: a prospective study with 2–5 year follow‐up. Human Reproduction 2003;18(9):1922–7. | |

Banerjee S, Ballard K, Lovell D, et al. Deep and superficial endometriotic disease: the response to radical laparoscopic excision in the treatment of chronic pelvic pain. Gynecological Surgery 2006;3(3):199–205. | |

Surrey ES, Soliman AM, Johnson SJ, et al. Risk of developing comorbidities among women with endometriosis: a retrospective matched cohort study. Journal of Women's Health 2018;27(9):1114–23. | |

Shafrir AL, Palmor MC, Fourquet J, et al. Co‐occurrence of immune‐mediated conditions and endometriosis among adolescents and adult women. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology 2021;86(1):e13404. | |

Casalechi M, Vieira-Lopes M, Quessada MP, et al. Endometriosis and related pelvic pain: association with stress, anxiety and depressive symptoms. Minerva Obstetrics and Gynecology 2021;73(3):283–9. | |

Carbone MG, Campo G, Papaleo E, et al. The importance of a multi-disciplinary approach to the endometriotic patients: The relationship between endometriosis and psychic vulnerability. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2021;10(8):1616. | |

Lubián-López DM, Moya-Bejarano D, Butrón-Hinojo CA, et al. Measuring Resilience in Women with Endometriosis. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2021;10(24):5942. | |

Horne AW, Daniels J, Hummelshoj L, et al. Surgical removal of superficial peritoneal endometriosis for managing women with chronic pelvic pain: time for a rethink? BJOG 2019;126(12):1414. | |

(ESHRE) ESoHRaE. Endometriosis. Guideline of European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology 2022. | |

Reis FM, Santulli P, Marcellin L, et al. Superficial peritoneal endometriosis: clinical characteristics of 203 confirmed cases and 1292 endometriosis-free controls. Reproductive Sciences 2020;27(1):309–15. | |

Burks C, Lee M, DeSarno M, et al. Excision versus ablation for management of minimal to mild endometriosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology 2021;28(3):587–97. | |

Pundir J, Omanwa K, Kovoor E, et al. Laparoscopic excision versus ablation for endometriosis-associated pain: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology 2017;24(5):747–56. | |

Wright J, Lotfallah H, Jones K, et al. A randomized trial of excision versus ablation for mild endometriosis. Fertility and Sterility 2005;83(6):1830–6. | |

Healey M, Ang WC, Cheng C. Surgical treatment of endometriosis: a prospective randomized double-blinded trial comparing excision and ablation. Fertility and Sterility 2010;94(7):2536–40. | |

Riley KA, Benton AS, Deimling TA, et al. Surgical excision versus ablation for superficial endometriosis-associated pain: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology 2019;26(1):71–7. | |

Nowak-Psiorz I, Ciećwież SM, Brodowska A, et al. Treatment of ovarian endometrial cysts in the context of recurrence and fertility. Advances in Clinical and Experimental Medicine: Official Organ Wroclaw Medical University 2019;28(3):407–13. | |

Gosset A, Escanes C, Pouilles J-M, et al. Bone mineral density in women with deep infiltrating endometriosis who have undergone early bilateral oophorectomy. Menopause 2021;28(3):300–6. | |

Wong J, Murji A, Sunderji Z, et al. Unnecessary bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy at the time of hysterectomy and potential for ovarian preservation. Menopause 2021;28(1):8–11. | |

Hart RJ, Hickey M, Maouris P, et al. Excisional surgery versus ablative surgery for ovarian endometriomata. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008(2). | |

Alborzi S, Momtahan M, Parsanezhad ME, et al. A prospective, randomized study comparing laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy versus fenestration and coagulation in patients with endometriomas. Fertility and Sterility 2004;82(6):1633–7. | |

Alborzi S, Ghotbi S, Parsanezhad ME, et al. Pentoxifylline therapy after laparoscopic surgery for different stages of endometriosis: a prospective, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology 2007;14(1):54–8. | |

Beretta P, Franchi M, Ghezzi F, et al. Randomized clinical trial of two laparoscopic treatments of endometriomas: cystectomy versus drainage and coagulation. Fertility and Sterility 1998;70(6):1176–80. | |

Carmona F, Martínez-Zamora MA, Rabanal A, et al. Ovarian cystectomy versus laser vaporization in the treatment of ovarian endometriomas: a randomized clinical trial with a five-year follow-up. Fertility and Sterility 2011;96(1):251–4. | |

Candiani M, Ottolina J, Schimberni M, et al. Recurrence rate after “one-step” CO2 Fiber laser vaporization versus cystectomy for ovarian Endometrioma: a 3-year follow-up study. Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology 2020;27(4):901–8. | |

Busacca M, Riparini J, Somigliana E, et al. Postsurgical ovarian failure after laparoscopic excision of bilateral endometriomas. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2006;195(2):421–5. | |

Muzii L, Achilli C, Bergamini V, et al. Comparison between the stripping technique and the combined excisional/ablative technique for the treatment of bilateral ovarian endometriomas: a multicentre RCT. Human Reproduction 2016;31(2):339–44. | |

Younis JS, Shapso N, Fleming R, et al. Impact of unilateral versus bilateral ovarian endometriotic cystectomy on ovarian reserve: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Human Reproduction Update 2019;25(3):375–91. | |

Chapron C, Fauconnier A, Dubuisson JB, et al. Deep infiltrating endometriosis: relation between severity of dysmenorrhoea and extent of disease. Human Reproduction 2003;18(4):760–6. | |

Arcoverde FVL, de Paula Andres M, Borrelli GM, et al. Surgery for endometriosis improves major domains of quality of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology 2019;26(2):266–78. | |

Meuleman C, Tomassetti C, D'Hoore A, et al. Surgical treatment of deeply infiltrating endometriosis with colorectal involvement. Human Reproduction Update 2011;17(3):311–26. | |

De Cicco C, Corona R, Schonman R, et al. Bowel resection for deep endometriosis: a systematic review. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 2011;118(3):285–91. | |

Byrne D, Curnow T, Smith P, et al. Laparoscopic excision of deep rectovaginal endometriosis in BSGE endometriosis centres: a multicentre prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2018;8(4):e018924. | |

Cavaco-Gomes J, Martinho M, Gilabert-Aguilar J, et al. Laparoscopic management of ureteral endometriosis: a systematic review. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 2017;210:94–101. | |

Chapron C, Dubuisson J-B. Laparoscopic treatment of deep endometriosis located on the uterosacral ligaments. Human Reproduction 1996;11(4):868–73. | |

Angioli R, Nardone CDC, Cafà EV, et al. Surgical treatment of rectovaginal endometriosis with extensive vaginal infiltration: results of a systematic three-step vagino-laparoscopic approach. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 2014;173:83–7. | |

Hong DG, Kim JY, Lee YH, et al. Safety and effect on quality of life of laparoscopic Douglasectomy with radical excision for deeply infiltrating endometriosis in the cul-de-sac. Journal of Laparoendoscopic & Advanced Surgical Techniques 2014;24(3):165–70. | |

Fritzer N, Tammaa A, Salzer H, et al. Dyspareunia and quality of sex life after surgical excision of endometriosis: a systematic review. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 2014;173:1–6. | |

Chapron C, Bourret A, Chopin N, et al. Surgery for bladder endometriosis: long-term results and concomitant management of associated posterior deep lesions. Human Reproduction 2010;25(4):884–9. | |

Gonçalves DR, Galvão A, Moreira M, et al. Endometriosis of the bladder: Clinical and surgical outcomes after laparoscopic surgery. Surg Technol Int 2019;15:275–81. | |

Kovoor E, Nassif J, Miranda-Mendoza I, et al. Endometriosis of bladder: outcomes after laparoscopic surgery. Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology 2010;17(5):600–4. | |

Pontis A, Nappi L, Sedda F, et al. Management of bladder endometriosis with combined transurethral and laparoscopic approach. Follow-up of pain control, quality of life, and sexual function at 12 months after surgery. Clinical and Experimental Obstetrics & Gynecology 2021;43(6):836–9. | |

Schonman R, Dotan Z, Weintraub AY, et al. Deep endometriosis inflicting the bladder: long-term outcomes of surgical management. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics 2013;288(6):1323–8. | |

Wills HJ, Reid GD, Cooper MJ, et al. Fertility and pain outcomes following laparoscopic segmental bowel resection for colorectal endometriosis: a review. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2008;48(3):292–5. | |

Kaufman LC, Smyrk TC, Levy MJ, et al. Symptomatic intestinal endometriosis requiring surgical resection: clinical presentation and preoperative diagnosis. Official Journal of the American College of Gastroenterology| ACG 2011;106(7):1325–32. | |

Daraï E, Dubernard G, Coutant C, et al. Randomized trial of laparoscopically assisted versus open colorectal resection for endometriosis: morbidity, symptoms, quality of life, and fertility. Annals of Surgery 2010;251(6):1018–23. | |

Kondo W, Bourdel N, Tamburro S, et al. Complications after surgery for deeply infiltrating pelvic endometriosis. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 2011;118(3):292–8. | |

de Almeida A, Fernandes LF, Averbach M, et al. Disc resection is the first option in the management of rectal endometriosis for unifocal lesions with less than 3 centimeters of longitudinal diameter. Surg Technol Int 2014;24:243–8. | |

Bourdel N, Comptour A, Bouchet P, et al. Long‐term evaluation of painful symptoms and fertility after surgery for large rectovaginal endometriosis nodule: a retrospective study. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 2018;97(2):158–67. | |

Sandström A, Bixo M, Johansson M, et al. Effect of hysterectomy on pain in women with endometriosis: a population‐based registry study. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 2020;127(13):1628–35. | |

Shakiba K, Bena JF, McGill KM, et al. Surgical treatment of endometriosis: a 7-year follow-up on the requirement for further surgery. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2008;111(6):1285–92. | |

Martin DC. Hysterectomy for treatment of pain associated with endometriosis. Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology 2006;13(6):566–72. | |

Namnoum AB, Hickman TN, Goodman SB, et al. Incidence of symptom recurrence after hysterectomy for endometriosis. Fertility and Sterility 1995;64(5):898–902. | |

Nnoaham KE. A multi-centre study of the impact of endometriosis on health-related quality of life and work productivity. Oxford University, UK, 2011. | |

Zhang S, Gong TT, Wang HY, et al. Global, regional, and national endometriosis trends from 1990 to 2017. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2021;1484(1):90–101. | |

evaluation Iohma. Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. | |

Chapron C, Lang J-H, Leng J-H, et al. Factors and regional differences associated with endometriosis: a multi-country, case–control study. Advances in Therapy 2016;33(8):1385–407. | |

Menakaya UA. Managing Endometriosis in Sub-Saharan Africa: Emerging Concepts and New Techniques. Afr J Reprod Health 2015;19(2):13–6. | |

(WHO) WHO. Endometriosis. 2021. | |

Rowe H, Quinlivan J. Let's not forget endometriosis and infertility amid the covid-19 crisis. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 2020;41(2):83–5. | |

Pizzol D, Trott M, Grabovac I, et al. Laparoscopy in Low-Income Countries: 10-Year Experience and Systematic Literature Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18(11). | |

Alfa-Wali M, Osaghae S. Practice, training and safety of laparoscopic surgery in low and middle-income countries. World J Gastrointest Surg 2017;9(1):13–8. | |

Bougie O, Yap MI, Sikora L, et al. Influence of race/ethnicity on prevalence and presentation of endometriosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG 2019;126(9):1104–15. | |

Farland LV, Horne AW. Disparity in endometriosis diagnoses between racial/ethnic groups. BJOG 2019;126(9):1115–6. | |

Fourquet J, Zavala DE, Missmer S, et al. Disparities in healthcare services in women with endometriosis with public vs. private health insurance. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2019;221(6):623.e1–.e11. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards program CLICK HERE)