This chapter should be cited as follows:

Gupta S, Wijesinghe V, Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.418273

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Gynecology Module

Volume 7

Fistula

Volume Editors:

Professor Ajay Rane, James Cook University, Australia

Dr Usama Shahid, James Cook University, Australia

Chapter

Female Genital Fistula

First published: May 2023

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

Genital fistulas are abnormal communications between the female genital tract and bladder, ureters, urethra, or bowel. Historically, the first female genital fistula can be traced back to Egypt in 2050BC while the earliest reference to papyrus from Egypt is 1550BC. The incidence and etiology of fistulae vary geographically and remain a serious, debilitating condition for women worldwide.

DEFINITION

A fistula is an abnormal communication between two epithelial surfaces, which can occur between two hollow (or tubular) internal organs or between an internal hollow organ and the outer epithelial layer of the body.

A genital fistula is a communication of the urethra, bladder, ureter and/or rectum with the uterus, cervix and/or vagina. Such communications are, therefore, genitourinary and/or recto-vaginal.

Obstetric vesicovaginal fistulae (VVFs) are predominantly caused by unrelieved obstructed labor. Recto-vaginal fistulae (RVFs) are rarely seen in isolation, though they may coexist with VVFs in more severe cases of obstructed labor. Combined fistulae occur in 5–10% of cases.

In the event of obstructed labor, if sufficiently prolonged, the majority will result in fetal demise. The mothers are also at risk of dying, especially those who live in remote areas, devoid of adequate medical facilities. In the cases of those who survive, unrelieved obstructions can lead to the development of urinary or fecal fistulae and a resultant devastating and crippled life for the mother.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Obstetric fistula in low-resource settings

Although genital fistulae occur in women all around the world, obstetric fistulae most commonly occur in developing countries like Africa and Asia. A systematic review conducted over three and a half decades reported that 95.2% of fistulae in developing countries were a consequence of obstetric complications.1 According to the WHO, there are around 2 million women suffering from untreated genital fistulas worldwide with an estimated 50,000 to 100,000 new cases adding to the cohort each year, mostly in Sub-Saharan Africa. The recent estimates of the global prevalence of untreated obstetric fistula vary from 654,000 to 3,500,000. The countries with the highest prevalence of vaginal fistula are Uganda, Malawi, Nigeria, Benin, Sierra Leone, and Ethiopia.2 The yearly incidence in different countries, for example,

- Nigeria (250,000–300,000);

- Bangladesh (>70,000);

- Mali/Niger (>50,000);

- Ethiopia (>25,000);

- and in Tanzania (up to 1800).3

Lifetime prevalence was 3.0 cases per 1,000 women of reproductive age.2 This may still reflect the tip of the iceberg as the condition tends to occur mostly in the underdeveloped world, with the scarcity of diagnostic and treatment facilities. Most of the cases remain under-reported, being devoid of timely access to adequate health care facilities. Factors contributing to such high incidences include but are not limited to the following:4

- Poverty and a poor socioeconomic status

- Poor health literacy

- Poor nutritional status

- Early marriage and young child-bearing age

- Poor health infrastructure and inadequate antenatal/obstetric care

- Economic barriers

Obstetric fistula is a disease of poverty and the WHO has included diagnosis and management of obstetric fistula to sustainable development goal 3 – improving maternal health. Further, it is an indicator of maternal mortality and morbidity.

Urogenital fistula in resource-rich settings

Pelvic surgery is one of the leading causes of the development of over 90% of genital fistulae in developed countries and less often a sequelae of obstetric injury, severe pelvic pathology, malignancy, or radiation therapy.

A study in the United Kingdom showed a 0.12% incidence of vesicovaginal fistula following all types of hysterectomy.5 In the United States, estimates of urogenital fistula formation range from less than 0.5% to 10% after simple and radical hysterectomy, respectively. Incidence of the fistula was lower in hysterectomy for the benign disease after 50 years or more.5 Expectedly, a population-based study in Sweden, in 2018 reported that organ injury during hysterectomy was associated with a higher incidence of fistula formation (7%), compared to 0.4% with no organ injury5,6 It has been described with laparoscopic and robotic techniques, there might be an increase in the overall fistula formation rate. However, evidence is obviously contradicting with improving the learning curve of laparoscopic procedures.7,8

Radiation therapy causes end arteritis leading to poor healing and poor blood supply to dissected organs, which leads to fistula formation.

Inflammatory conditions like pelvic inflammatory disease, and inflammatory bowel disease leads to friable tissue, which leads to breakdown and hence fistula formation.

Etiological factors:

Obstetric causes

- Prolonged obstructed labor (commonest: 90.4%)2,9

- Destructive procedures during delivery

- Instrumental vaginal delivery

- Manual extraction of the placenta

- Cesarean delivery with or without hysterectomy

- Traditional defibulation (reconstructive procedures)

- Symphysiotomy (associated with ureterovaginal or urethrovaginal fistula)

Non-obstetric causes

- Traumatic

- Coital/sexual violence (4.3%)

- Accidental trauma

- Female genital mutilation (FGM)

- Infection

- Granulomatous infection

- Tuberculosis

- HIV infection

- Foreign body

- Congenital (rare)-ectopia vesicae, epispadias, ectopic ureters

- Genital prolapse surgery

- Neurological

- Malignancy-advanced cervical cancers

- Radiotherapy

- Iatrogenic (25% as reported in series from East Africa)

ETIOPATHOGENESIS

In resource-limited countries, obstructed labor is the most common etiology of vesicovaginal fistulas. The current trend of rising in post-operative fistula is seen in these settings due to improvement in the health care infrastructure.10

A significant factor in the development of fistulas is injuries resulting from traditional practices such as female genital mutilation. Further, sexual violence and the accessibility and quality of health care are paramount socio-economic determinants.

Obstructed labor – Obstructed labor is defined when the fetal head can no longer descent through the birth canal irrespective of adequate uterine contractions. All pregnant women are potentially at risk because obstruction can develop during any labor. When the fetus is not delivered by cesarean section in a timely manner, pressure on maternal tissue undergoes tissue necrosis. In limited-resource countries, three delays can result in an increase in prevalence and incidence of obstetric fistula.4

The maternal soft tissues (bladder, vagina, cervix, rectum) become compressed between the boney plates of the fetal head and the maternal pelvic bones leading to prolonged pressure on blood vessels causing ischemic necrosis. These necrotic tissues slough away usually after 1–2 weeks of the birth. But in cases of severe and prolonged obstructions fistula could be apparent immediately after the birth. An obstetric fistula is usually multiple in nature as pressure occurs on the vagina, cervix, bladder, and rectum during obstructed labor.

Tissue necrosis is the climax of the formation of fistula, but many factors interfere with the formation of fistula such as the amount of force exerted on the impacted tissues, the degree of distension of the bladder, the level in the pelvis at which labor has become obstructed, the blood flow through the affected tissues, the overall resilience of the tissues, and the amount of time this process continues.

The tissue surrounding a fistula is also in poor condition due to ischemia. The margins of the fistula are often heavily scarred and de-vascularized, potentially complicating future surgical repair compared to the fistula following a laceration.

Stillbirth rates of 84 to 93% have been reported by patients presenting with obstetric fistula.11,12 If labor is sufficiently prolonged, it cannot only result in fistula formation and stillbirth, but post-partum hemorrhage, uterine rupture, and maternal death. Those who survive birth are then faced with lifelong morbidities such as anatomical damage, pelvic insufficiency, or even renal failure.

Surgical complications – Most post-hysterectomy fistulas are small and are located at the vaginal cuff where the bladder was dissected off the lower uterine segment and cervix. A pool of urine leaking from the injured bladder prevents normal healing of the edges of the vaginal cuff, thereby allowing a fistula to form between the raw surfaces of the bladder and the vagina.

The postsurgical urogenital fistula may be caused by direct injury during dissection, which is frequently identified at the surgery or in the immediate postoperative period. However, clamp or crush injury, cautery, or suture impingement, kinking, or placement through the bladder or ureter. The key process in such instances is ischemic necrosis where the process takes from days up to a month and urine leakage may not be observed until sometime after surgery. Sometimes, intraperitoneal leakage can occur in absence of vaginal leakage.

Synthetic mesh in the repair of stress incontinence and pelvic prolapse can cause direct bladder injury or undue tension on the bladder causing ischemic necrosis and hence vesicovaginal fistula.

A small proportion of vesicovaginal fistulas in sub-Saharan Africa result from surgical complications usually associated with hysterectomy. Currently, access to surgical services is limited in many developing countries. As this access increases, the number of cases of fistula associated with surgery will increase.13 As the nation becomes developed the etiology of fistula shifts toward surgical, radiation, and inflammatory causations.14,15

Traditional practices – In some countries, a small number of obstetric fistulas result from injuries associated with traditional medical practices such as female genital mutilation or "salt packing".

Active campaigns throughout the world to eliminate these harmful practices, which nonetheless are still deeply rooted in many cultures. This can lead to direct injury causing fistula or obstructing vaginal birth due to scarring leading to obstetric fistula.

Salt packing is a traditional practice carried out during the post-partum period with intention of tightening the vagina. It may create a fistula by direct chemical burning, particularly after prolonged labor.

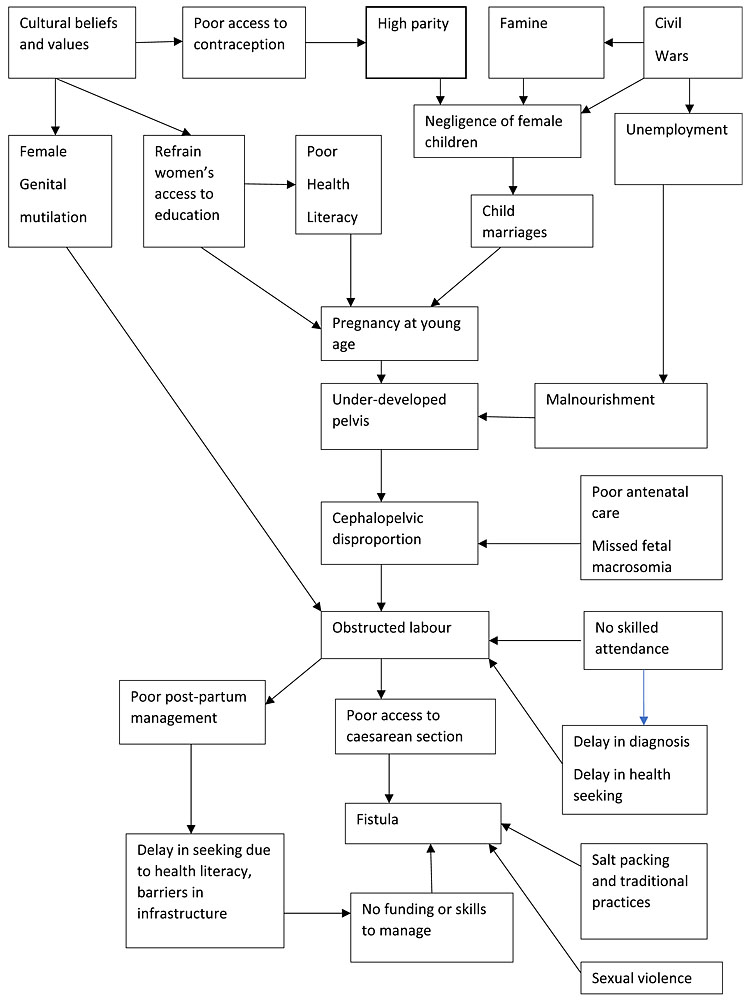

Economic and societal issues – Economic, societal, and cultural factors contribute to the circumstances in which injuries result in the obstetric fistula (Figure 1).

A small number of fistulas result from sexual violence (child marriage), and from complications of unsafe abortion.

1

Socio-economic cycle of female genital fistula

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Fistulas clinically present with painless leakage of urine, which may or may not be affected by the position. Some women present with increased vaginal discharge or fecal discharge from the vagina.

While localized anatomically, the fistula is an insult not limited to the affected site. The impact of a fistula far exceeds the boundaries of reproductive organs. Its complications can extend to not only other organ systems, but the patient’s mental-health and socio-economic standing.

Complications

Immediate complications

- Uterine rupture

- Fetal loss

- Post-partum sepsis

- Ischemic processes in pelvic organ tissues

- Spontaneous symphysiolysis

Delayed complications

- Continuous incontinence – watery vaginal discharge

- Genital tract injuries – vaginal and/or cervical stenosis leading to hematometra

- Recurrent urinary tract infections and urinary dermatitis with chronic excoriation, local hyperkeratosis and secondary ulceration

- Extra-genital damage – gastrointestinal damage, anal sphincter damage

- Renal damage – stricture of the lower ureter may lead to hydronephrosis and loss of renal function. Bladder and vaginal stones may develop due to concentrated urine

- Nerve damage – foot drop from the involvement of L5 root

Secondary consequences

- Malnutrition

- Dyspareunia/apareunia

- Amenorrhea

- Infertility – secondary to Asherman’s or Sheehan’s syndrome

- Bladder dysfunction – neuropathic bladder

- Contractures – up to 2% of fistula patients in Ethiopia suffer severe lower limb contractures

- Social stigma, divorce, and a life of exclusion

- Mental health – depression and psychological disorders

- Suicidal thoughts or attempts (in 40% of cases)

- Reduced life expectancy

Rare complications

- Cervical incompetence

- Uterine prolapse

CLASSIFICATION OF FISTULA

A classification system should

- Be descriptive, indicative as well as prognosticate (i.e., present a description, indicate the operative technique to be applied and expected outcome).

- Be a reliable tool for study and communication (a means to standardize terminology, and set universally agreed objective parameters of assessment).

- Help trainers select cases for trainees and help surgeons select cases for themselves according to competence.

GOH classification is the commonly used and internally and externally validated classification. Further, it is predictive of prognosis.

THE GOH CLASSIFICATION

The Goh Classification of Genito-Urinary Fistulae.16

Site (distance between external urinary meatus and distal edge of fistula) | |

Type 1 | >3.5 cm |

Type 2 | 2.5–3.5 cm |

Type 3 | 1.5 to just less than 2.5 cm |

Type 4 | <1.5 cm |

Size (length of the largest diameter) | |

A | <1.5 cm |

B | 1.5–3 cm |

C | >3 cm |

Scarring characteristics | |

I | None or only mild fibrosis (around fistula and/or vagina) and/or vaginal length >6 cm with normal vaginal capacity |

I i | Moderate or severe fibrosis (around fistula and/or vagina) and/or reduced vaginal length and/or reduced vaginal capacity |

I ii | Special consideration, e.g., radiation damage, ureteric involvement, circumferential fistula, previous repair |

ASSESSMENT AND DIAGNOSIS

To develop an appropriate treatment plan, it is important to assess the patient for the number, size, and exact location of fistula.

A detailed history and thorough examination are vital in confirming the etiopathological diagnosis and ruling out associated inflammation, edema, necrosis, and scarring at the site, which may defer the surgery planning.

Data needs to be collected at the patient’s first visit to the hospital or clinic, and all the way through to admission, in-patient care, discharge, and follow-up. Data collection facilitates auditing and assessments at the core of good training and therefore is an essential step toward providing good patient care.

Basic data collection includes the following:

- Recording data from the patient’s personal and clinical history

- Recording data from the patient’s examination

- Recording data from the patient’s admission, surgical procedure, post-operative management, and discharge

- Recording data from all follow-up visits

- Performing audits

- Building a database for personal records as well as institutional audits and multi-center studies.

The following information must be noted during history taking:

- Patient characteristics:

- Name

- Age and age at marriage. When the patient does not know her age (which occurs frequently) she is asked if she was married before or after menarche, and/or how many periods she had before she became pregnant

- Address (specifically noting rurality)

- Marital status

- Presenting complaint

- Main clinical concern

- Duration of complaint/main concern parity; sex of living and dead children

- Social history

- Members of the patient’s household

- Patient’s education

- Patient’s occupation if she is currently working outside the household

- How she heard about/was referred to the center

- Obstetric history:

- Labor duration

- Place of delivery (home, health institution, other)

- Time spent in labor and time spent at home before being helped, and who helped her at home. Time spent at the health institution before she received help there

- Mode of delivery: Spontaneous vaginal delivery; instrumental delivery (forceps or vacuum); destructive delivery; symphysiotomy; cesarean delivery, with or without hysterectomy

- Obstetric outcome: Live birth, stillbirth, early neonatal death, sex of baby

- Any other complaint: Vaginal bleeding or discharge, inability to walk properly or absence of menses. If the menses have resumed, how long after delivery?

- Fistula history: Any previous fistula repair? Where? Was it successful? (The answer indicates whether the present fistula is a new or an old one, or an unsuccessfully repaired one)

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

General: Gross nutritional status, developmental stage, and mental status.

Systemic: Review of the urogenital, respiratory, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and musculoskeletal systems.

The neurologic signs and symptoms (such as foot drop or saddle anesthesia) are caused by obstructed labor. Additionally, if anal reflex and pudendal nerve function are impaired, residual stool and or flatal incontinence may continue to trouble the patient despite good anatomic repair.

The external genitalia are examined for

- Signs of ulceration and excoriation due to hyperkeratosis ("urine dermatitis")

Bleeding, stones, genital mutilation, perineal tears

Speculum and digital examination: This part of the examination allows us to diagnose genital fistula and to take note of any characteristics that may affect treatment and outcome.

During the examination, the following are checked:

- Patency of the reproductive tract: The vagina, uterus, or cervix can be occluded, and the cervix may even be missing.

- Location (anterior and/or posterior) and extent of vaginal scarring; scarring often appears as a thick band of scar tissue on the posterior vaginal wall.

- Fistula number (there can be more than one bladder or rectal fistula), fistula size, and location.

- Urethral length and whether the urethra is circumferential (one can feel a bony structure anteriorly when the urethra has been severed from the bladder).

- Presence of bladder stones, anal sphincter status and any other abnormality in the genital tract.

- Bladder capacity (difficult to evaluate pre-operatively, but can be roughly assessed by sounding the bladder with a metal catheter or probe).

- The examination will be difficult in case the previous hysterectomy anatomy of the vagina is altered. Introital narrowing will make it impossible in some cases as previous radiation and malignancies. Examination under anesthesia is an alternative in such cases.

- Dye test – The bladder will be packed with gauze swabs or tampons (using each swab for the upper, middle, and lower parts of the vagina). The bladder can be filled with indigo carmine or methylene blue mixed with saline using a catheter. Then the catheter is clamped and the patient is asked to walk and perform the Valsalva maneuver. Then the bladder will be emptied, and the catheter is removed without soiling the introitus. Staining of the vaginal swab is indicative of VVF.

- Oral phenazopyridine (100 or 200 mg) is taken on the day of the test 1 to 2 hours before the examination to turn the urine orange. In combination with the above test, it could be used to distinguish urine leaking from the ureterovaginal fistula.

- In many settings, these tests are obsolete as the findings are not confirmatory of the site.

- Vesicoureteral reflex can cause blue color urine in ureters and complex communications can give rise to false-positive and negative results. And performing these tests can introduce infection. Further, patient discomfort is considerable.

INVESTIGATIONS

Aims of investigations, when planning the investigations with the patients, Significant variations have been noted from center to center. Availability of facilities and patient factors (allergies, affordability, poor renal function) play a major role in determining the investigations.

- Diagnose the type, site, and cause of the fistula

- Exclude co-morbidities infection, renal damage, and metabolic dysfunctions

- Assess the fitness for corrective surgery

- Assess the mental health

- Cystoscopy is performed in cases suspecting VVF. Fistula tracts can be seen directly and suture materials that have traversed the bladder can be removed. Further cystoscopy can be used for the repair of VVF in combination with laparoscopic and vaginal surgeries. The absence of ureteric jets may be indicative of ureteric injury. A fluoroscopic cystogram can be performed to visualize the bladder and fistula tract. In this case, fluorescein dye will be injected into bladder using a foley catheter. CT cystogram or CECT (delayed phase) can be used to outline the bladder margins and fistula tracts. Fistula will be indicated as a hypodense area. MRI has replaced most of the above investigations.17,18 The specific protocol needs to be communicated with the local radiology team before ordering the investigation like CT and MRI.

- In cases where ureteric injury is suspected, a ureteroscopy visualization is a viable option. In suspected cases, ureteric stenting can be performed during the same procedure. Retrograde pyelogram ureteric tract and further, stenting can be accomplished during this procedure. An intravenous pyelogram is useful mostly in cases of delayed diagnosis, but the usefulness is limited by impaired renal function and complete traversing of ureters may impair the filling of contrast on a particular side.19 MRI has better soft tissue demarcation and has replaced many of the above investigations due to its superior sensitivity.

- Authors highly recommend communication with the local radiological and uro-surgical team prior to organizing diagnostic investigations.

- At the onset of the suspicion, renal function testing must be ordered. Rapid deterioration warrants urgent interventions such as percutaneous nephrostomy. Urine microscopy and culture are required to rule out infection. Pre-treatment prior to corrective surgery is mandatory to optimize the outcome.

- Patients' health needs to optimize associated diabetes, anemia, and hypoalbuminemia, which hinder the recovery of repair.

- Cardiac and respiratory co-morbidities need to be addressed as fistula repair surgery is time-consuming. Significant co-morbidities can limit the surgical options for the patient.

- Mental health assessment is an important component prior to embarking on corrective measures. Setting the goal with the patient. Managing anxiety and depression in conjunction with physical investigations and corrective surgery is paramount.

FISTULA PREVENTION

The most crucial factor in preventing genital fistula formation is the provision of competent maternal care with improved access to emergency obstetric services. Enhanced surveillance of labor with adequate use of partograms and the development of skilled fistula repair centers at places with higher fistula prevalence can help reduce the burden. Universally improving the level of health education amongst young girls and women, increasing awareness of family planning services and improving the social and nutritional status of women, plays a vital role in the prevention.20 Women need to be educated about the importance of delaying the age of marriage with early births, spacing desired births, and limiting the family size. Incorporating all these factors along with eliminating unsafe abortion practices will avert one-third of maternal and one-quarter of neonatal mortality.21 Adequate family planning services can help achieve successful pregnancy in patients with repaired fistula. It has mentioned the use of Haddox matrix in analyzing the factors influencing fistula formation and stresses on challenges in preventing it, largely because of complex interactions among medical, social, economic, and environmental factors present in the countries where fistulas are prevalent.22

To prevent fistula formation in case of prolonged or obstructed labor:

- Insert a urethral catheter for free drainage of urine and keep the catheter in place for at least 2 weeks (with no apparent damage) or 4–6 weeks in case of a small fistula

- Sitz-baths twice a day

- Encourage the patient to drink at least 2.5 liters of fluid per day

- Excise any necrotic tissue from the vagina as soon as possible

- Treat intercurrent infections with antibiotics

- Teach pelvic floor muscle exercises to all patients

- Set up appointments for regular follow-up visits

The above approach can prevent fistula formation in 20% of cases.

According to the WHO, preventing and managing obstetric fistula will contribute to improved maternal health and the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG-3).

Higher rates of bladder and ureteric injuries are noted during the learning curve of surgeons. Hence step-wise training in trainees is one point to consider worldwide.23 Pre–operative assessment and anticipating difficulties and escalating to tertiary levels is standard practice, However, unanticipated difficulties are not uncommon during surgery, understanding of pelvic anatomy, proper ureteric and bladder dissection and restoring the normal anatomy prior to resection is the principal to successful surgery.

When difficulties are beyond the capabilities of the surgeon, surgical or uro-surgical input is mandatory.

In cases of ureteric and bladder damage is suspected liaising with the urology team needs to be considered. Cystoscopy to visualize the bladder and the presence of ureteric jets does not exclude iatrogenic injuries indefinitely.

Prophylactic stenting is a debatable topic. Some experts believe it prevents injury, on the contrary, some believe it increases the chances of injury as it limits mobility and reduces the pliability.

CT-IVU is recommended prior to removal of the catheter in case of bladder injuries to confirm the healing as in some women fistula has developed after proper repair and catheter being in situ for 10–14 days.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- Identify the high-risk women for developing fistula.

- Seek expert opinion when suspecting an intra-operative injury.

- Social and political interventions to prevent obstetric fistula.

- Support the countries without access to comprehensive maternal care.

- A support system to develop care for postpartum women with obstetric fistula.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) of this chapter declare that they have no interests that conflict with the contents of the chapter.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

REFERENCES

Cowgill KD, Bishop J, Norgaard AK, et al. Obstetric fistula in low-resource countries: an under-valued and under-studied problem – systematic review of its incidence, prevalence, and association with stillbirth. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth [Internet] 2015;15:193. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4550077/. | |

Maheu-Giroux M, Filippi V, Samadoulougou S, et al. Prevalence of symptoms of vaginal fistula in 19 sub-Saharan Africa countries: a meta-analysis of national household survey data. Lancet Glob Health 2015;3(5):e271–8. | |

Cichowitz C, Watt MH, Mchome B, et al. Delays contributing to the development and repair of obstetric fistula in northern Tanzania. Int Urogynecology J 2018;29(3):397–405. | |

Hilton P, Cromwell D. The risk of vesicovaginal and urethrovaginal fistula after hysterectomy performed in the English National Health Service – a retrospective cohort study examining patterns of care between 2000 and 2008. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol [Internet] 2012;119(12):1447–54. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2012.03474.x. | |

Hesselman S, Bergman L, Högberg U, et al. Risk of fistula formation and long-term health effects after a benign hysterectomy complicated by organ injury: A population-based register study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand [Internet] 2018;97(12):1463–70. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/aogs.13450. | |

Kobayashi E, Nagase T, Fujiwara K, et al. Total laparoscopic hysterectomy in 1253 patients using an early ureteral identification technique. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2012;38(9):1194–200. | |

Mann WJ, Arato M, Patsner B, et al. Ureteral injuries in an obstetrics and gynecology training program: etiology and management. Obstet Gynecol 1988;72(1):82–5. | |

Trovik J, Thornhill HF, Kiserud T. Incidence of obstetric fistula in Norway: a population-based prospective cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2016;95(4):405–10. | |

Danso KA, Martey JO, Wall LL, et al. The epidemiology of genitourinary fistulae in Kumasi, Ghana, 1977–1992. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 1996;7(3):117–20. | |

Cichowitz C, Watt MH, Mchome B, et al. Delays contributing to the development and repair of obstetric fistula in northern Tanzania. Int Urogynecology J 2018;29(3):397–405. | |

Arrowsmith S, Hamlin EC, Wall LL. Obstructed labor injury complex: obstetric fistula formation and the multifaceted morbidity of maternal birth trauma in the developing world. Obstet Gynecol Surv 1996;51(9):568–74. | |

Ngongo CJ, Raassen T, Lombard L, et al. Delivery mode for prolonged, obstructed labour resulting in obstetric fistula: a retrospective review of 4396 women in East and Central Africa. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol 2020;127(6):702–7. | |

Tasnim N, Bangash K, Amin O, et al. Rising trends in iatrogenic urogenital fistula: A new challenge. Int J Gynecol Obstet [Internet] 2020;148(S1):33–6. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/ijgo.13037. | |

Kochakarn W, Ratana-Olarn K, Viseshsindh V, et al. Vesico-vaginal fistula: experience of 230 cases. J Med Assoc Thail Chotmaihet Thangphaet 2000;83(10):1129–32. | |

Kochakarn W, Pummangura W. A new dimension in vesicovaginal fistula management: an 8-year experience at Ramathibodi hospital. Asian J Surg 2007;30(4):267–71. | |

Frajzyngier V, Ruminjo J, Barone MA. Factors influencing urinary fistula repair outcomes in developing countries: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol [Internet] 2012;207(4):248–58. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3398205/. | |

Abou-El-Ghar ME, El-Assmy AM, Refaie HF, et al. Radiological diagnosis of vesicouterine fistula: role of magnetic resonance imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging JMRI 2012;36(2):438–42. | |

Hyde BJ, Byrnes JN, Occhino JA, et al. MRI review of female pelvic fistulizing disease. J Magn Reson Imaging JMRI 2018;48(5):1172–84. | |

Sunday-Adeoye I, Ekwedigwe KC, Isikhuemen ME, et al. Intravenous urography findings in women with ureteric fistula. Pan Afr Med J [Internet] 2018;30:203. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6294966/. | |

Changing trends in the etiology and management of vesicovaginal fistula – Malik – 2018 – International Journal of Urology – Wiley Online Library [Internet]. [cited 2022 Jun 25]. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/iju.13419. | |

Fauveau V, Sherratt DR, de Bernis L. Human resources for maternal health: multi-purpose or specialists? Hum Resour Health [Internet] 2008;6(1):21. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-6-21. | |

Wall LL. A Framework for Analyzing the Determinants of Obstetric Fistula Formation. Stud Fam Plann [Internet] 2012;43(4):255–72. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1728-4465.2012.00325.x. | |

Patil SB, Guru N, Kundargi VS, et al. Posthysterectomy ureteric injuries: Presentation and outcome of management. Urol Ann 2017;9(1):4–8. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards program CLICK HERE)