This chapter should be cited as follows:

Parikh S, Hanna H, et al., Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.420053

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Gynecology Module

Volume 8

Gynecological endoscopy

Volume Editors:

Professor Alberto Mattei, Director Maternal and Child Department, USL Toscana Centro, Florence, Italy

Dr Federica Perelli, Obstetrics and Gynecology Unit, Ospedale Santa Maria Annunziata, USL Toscana Centro, Florence, Italy

Chapter

Laparoscopic Entry Techniques

First published: September 2023

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

Initial abdominal entry is essential in performing laparoscopic procedures and creation of pneumoperitoneum. While many complications related to laparoscopy are due to initial trocar entry, abdominal entry can be accomplished safely by various methods. There is no consensus on the optimal technique to avoid related complications. The most serious complications related to laparoscopic entry include major vascular, bowel, and visceral injury. However, these complications are typically rare, and the literature estimates about 50% of inadvertent laparoscopic injuries to vital organs and vessels occur at the time of entry. The incidence of bowel wall perforation has been reported at 0–0.5% and major vessel injury at 0.01–1.0% of cases.1,2

Entry location is dependent on the patient's body habitus, surgical history, surgeon preference, experience of entry technique, and expected intra-abdominal pathology. In this chapter, we discuss the most common methods of abdominal entry which include Veress needle, open Hasson technique, and direct trocar entry.

ENTRY CONSIDERATIONS

Access Points

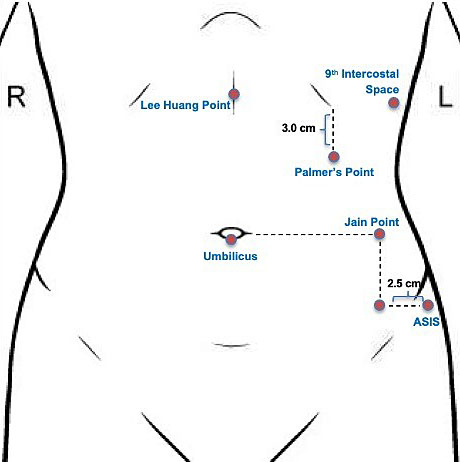

As previously mentioned, the creation of pneumoperitoneum is critical in performing laparoscopic surgery, and proper technique is mandatory to establish safe laparoscopic entry. Initial trocar entry site is based on surgeon’s preference and comfort, patient’s surgical history, and patient anatomy. Common entry points include umbilical, left upper quadrant or Palmer’s point, right upper quadrant, mid-abdomen (Lee Huang point), vaginal or uterine fundus, and Jain’s point (Figure 1).

1

Various entry points for initial laparoscopic entry.

Initial laparoscopic entry should always be performed with the patient lying flat in supine position. Trendelenburg positioning should be avoided as any degree of angulation may risk unnecessary direct vascular injury with respect to the major abdominal vessels upon entry.

At our institution, we prefer the left upper quadrant entry given our high rate of complex surgical patients. Palmer’s point was described by the French gynecologist, Raoul Palmer, in the early part of the 20th century.3,4,5 This technique is generally considered a reliable entry point in patients with previous midline laparotomies, presence of abdominal mesh or umbilical hernia repair, pelvic and abdominal adhesions, and extremes in body mass index (BMI). Prior review of women having laparoscopy after laparotomy show that more than 50% of women with a midline vertical incision will have intra-abdominal adhesions between the anterior abdominal wall and omentum or bowel and greater than 30% of these women will have severe umbilical adhesions with potential for bowel injury.4,6,7 Obesity can also distort umbilical subcutaneous planes. The aortic bifurcation in relationship to the umbilicus lies 1–2 cm below the umbilicus in extremely thin patients. In obese women the umbilicus may shift significantly caudally. Thus, umbilical entry may not be ideal in these patients owing to the risk of major vessel injury. Additionally, gastric decompression is recommended when using this entry point in the left upper quadrant and may be achieved by placing an oral gastric tube to suction. Relative contraindications to left upper quadrant entry include inability to decompress the stomach, history of splenectomy or gastric surgery, and hepatomegaly.8

ENTRY TECHNIQUES

Closed (Veress)

The term pneumoperitoneum was first coined by Otto Goetze. Decades later, a pulmonologist named János Veres introduced an insufflation needle in 1937 that was previously described by Goetze.9 The Veress needle continues to be used widely as an efficient and safe mode of entry technique in laparoscopy.

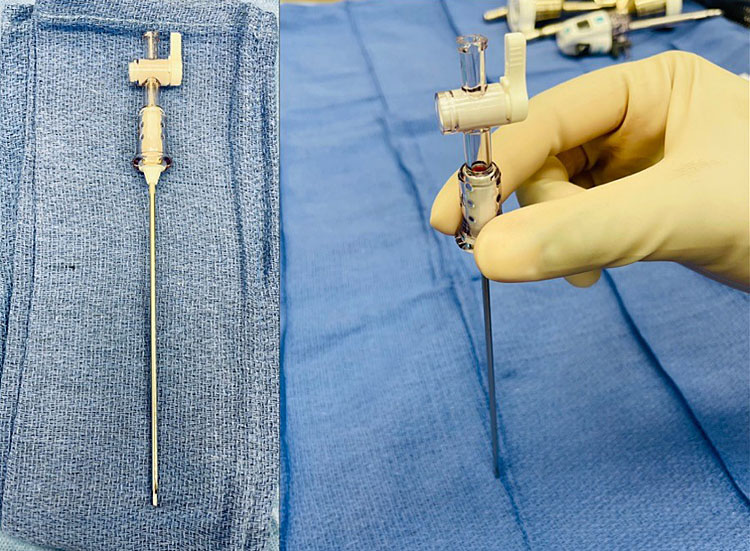

The Veress is a spring-loaded needle that is available as a reusable or disposable option (Figure 2). The outer sheath is sharp, while the inner sheath contains a dull tip with a spring mechanism that retracts back when resistance is encountered. When the Veress needle traverses the abdominal layers and enters the peritoneal cavity, resistance decreases, and the dull tip is exposed to protect intra-abdominal structures from the sharp tip. As good practice, it is recommended to check the mechanics of the Veress needle prior to insertion, even with the disposable instruments.3

2

Disposable Veress needle.

Entry point for the Veress needle may utilize any of the above-mentioned entry locations including the umbilicus, left upper quadrant, ninth intercostal space, transuterine, or Jain’s point. Depending on the patient's individual characteristics such as surgical history and BMI, one entry location may be more suitable over another.3

Left upper quadrant entry

As previously stated, we prefer Palmer’s point at our institution, located in the left midclavicular line 3 cm below the costal margin. After confirming orogastric or nasogastric tube placement to decompress the stomach, a skin incision is made at the desired abdominal entry site and the Veress needle is inserted at a 90° angle to the abdominal wall. In the left upper quadrant, generally three “pops” are felt as the needle traverses the aponeuroses of the internal and external oblique muscles, transversalis fascia, and peritoneum. Gas tubing is attached to the Veress needle and confirmation of intra-abdominal entry with an opening pressure of less than 10 mmHg confirms correct placement. Once the abdomen is insufflated to the predetermined abdominal pressure, initial 5 mm trocar may be placed either directly or with direct optical entry. This technique is very valuable in morbidly obese patients, and we use it in all patients with previous abdominal surgeries (Figure 3, Video 1).

3

Veress needle entry technique in a morbidly obese patient with history of two prior cesarean sections. Peritoneal entry was confirmed after meeting a decrease in resistance and cavity pressure <10 mmHg.

1

Veress technique.

Safety tests that can be used to confirm Veress needle placement include irrigation or aspiration test, hanging drop test, and gas insufflation. Observational studies comparing these tests show that low intraperitoneal pressure is the most reliable in confirming correct Veress needle placement.8 Thus, at our institution, we confirm Veress needle entry by initial insufflation gas pressure of ≤10 mmHg. In agreement with previous guidelines set forth by the Middlesborough consensus document, we typically insufflate with carbon dioxide to intra-abdominal pressure of 25 mmHg temporarily to establish sufficient pneumoperitoneum. At this pressure, the distance between the abdominal wall and underlying structures is about 10 cm, which minimizes the risk of vascular and visceral injury even with enough force applied with difficult trocar insertion.6

Numerous publications have reported that the Veress technique is a popular entry method around the world among gynecologists.1 A Cochrane review of laparoscopic entry techniques from 2019 showed there is insufficient and low-quality evidence to show any differences in vascular, visceral, or solid organ injury with direct versus Veress or open entry technique.1 However, following the Cochrane review, Raimondo et al. reviewed 25 randomized controlled studies and reported preference for the direct trocar method over the Veress needle or open entry owing to a lower risk of omental injury, failed entry, and extraperitoneal insufflation and infection at the trocar site.2 Common reasons of Veress entry failure include underestimation of preperitoneal fat, tracking, insufflation of preperitoneal space, unexpected adhesions, and advancing the needle too deep under the omentum. The rate of complications increases with each subsequent attempt. It is recommended that no more than three attempts should be made with any of the entry methods and an alternative entry option should be utilized in these cases.4

Direct

Direct trocar entry technique is a safe alternate method for initial abdominal entry in laparoscopic surgery. While the Veress needle requires three blind steps in entry (insertion, insufflation, trocar placement), direct entry is initiated with only one blind step with trocar insertion.10 To perform this technique, a small infraumbilical incision is made to the diameter of desired trocar/cannula system. The abdominal wall is lifted with a non-dominant hand, and the trocar is carefully inserted into the abdominal cavity through this incision with a twisting motion, aiming towards the pelvis until there is a loss of resistance. The angle in thin and normal size patients should be 45° with respect to the patient’s abdominal wall at the level of the umbilicus. While in obese patients an angle of 90° to the abdominal wall is used during entry. To confirm intra-abdominal entry, insufflation tubing should be attached to the trocar and a laparoscope introduced.

Direct visual entry

Direct optical access technique can also be performed with or without establishment of pneumoperitoneum with the Veress needle. However, an optical trocar is needed to use this technique. To perform this technique without establishment of pneumoperitoneum, a 5–10 mm skin incision is made at a desired primary port site. Like direct trocar entry, the abdominal wall is lifted with non-dominant hand, and an optical trocar with a 5–10 mm laparoscope is gently advanced through the abdominal layers using a twisting motion until peritoneal fat or bowel is visualized to indicate peritoneal entry. The trocar sheath is then removed, and the laparoscope is then reinserted to confirm abdominal entry. A similar technique can also be used if pneumoperitoneum is already established with the Veress needle. To confirm entry, typically a dark circular space is visualized at the tip of the trocar after passing the subcutaneous and muscle layers of the abdomen with a rush of gas will be heard from the peritoneal cavity to indicate that the appropriate depth has been reached.8,3

As with all other techniques, it is important to assess the entry point for any vascular or visceral injury. The advantage of using direct trocar entry is that it is a faster entry method than Veress needle or open technique. There is also less gas leak around the primary port compared to open Hasson approach and reduced risk of inadvertent injury with optical entry compared to closed technique.11 A Cochrane review on laparoscopic entry technique from 2019 concluded that there is moderate-quality evidence to show that there is a reduction in failed abdominal entry by direct entry compared to Veress (OR 0.24, 95% CI 0.17–0.34).1 However, this approach does require knowledge of the abdominal wall layers and ability in distinguishing between pre-peritoneal and omental fat.4

Open (Hasson)

Open entry technique was first developed and described by Dr Harrith Hasson in 1971.12 This technique has become widely accepted and is constantly being modified to improve its practice.

Open entry is generally preferred in patients with a history of previous surgeries and intra-abdominal adhesions as well as in cases where other entry methods have failed.6 This technique can be used in any quadrant of the abdomen, but it is most used at the central umbilical site.

Ports used for open entry differ from standard ports used in laparoscopy. These ports are typically blunt and lack bladed or sharp trocars. A well-known example of an open laparoscopy entry port is the Hasson port (Figure 4). This trocar port consists of a system that allows the abdominal fascia to be attached to the port using sutures to stabilize the port to the patient. Other ports may have a balloon to stabilize the port as well as maintain pneumoperitoneum.

4

Hasson trocar for open Hasson technique for laparoscopic entry.

The following discusses the technical aspect of open entry technique (Video 2):

2

Open Hasson technique.

- Skin incision is made at desired entry point;

- Subcutaneous fat is bluntly dissected using a S retractor;

- Once fascia is identified, Kocher clamps are used to grasp the fascia or umbilical stalk if entry is through umbilicus;

- Fascia is incised and tagged with stay sutures which will be used to secure the port;

- The preperitoneal fat is bluntly dissected and the peritoneum is tented up using a clamp. The peritoneum is sharply dissected to enter the abdominal cavity;

- The underside of the abdominal wall should be swept with index finger to clear omentum or bowels and confirm the absence of adhesions;

- A blunt-ended or Hasson trocar is placed through incision into the abdominal cavity and secured with stay sutures;

- Insufflation tubing is attached to the port;

- At the end of the procedure, stay sutures are cut or detached to remove the port.

The greatest advantage of open entry technique is that it allows for precise, controlled entry into the intra-abdominal cavity. However, the open Hasson technique can be challenging in very obese patients as it is difficult to gain abdominal entry through a small, 3 cm skin incision due to depth of subcutaneous fat. As previously mentioned, initial trocar insertion is perhaps the most important and dangerous step in minimally invasive surgery. Champault et al. have shown that 83% of vascular injuries, 75% of bowel injuries, and 50% of local hemorrhage injuries during laparoscopy were caused during primary trocar insertion.13,14,15,16,17

Despite the findings of the 2019 Cochrane review by Ahmad et al., an earlier prospective/retrospective review analyzed closed versus open entry laparoscopy and found no major vascular injuries and one visceral injury among 5900 patients.1

vNOTES

Transvaginal natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery is an emerging surgical approach for minimally invasive surgery in which the vagina is used as a “natural orifice” or entry point into the peritoneal cavity for single-port laparoscopy. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends the vaginal route as the gold standard approach to hysterectomy as there is evidence of fewer complications, decreased operative time and cost, and shorter hospital stay in comparison to laparoscopic and abdominal hysterectomies. vNOTES can be used to broaden the feasibility of vaginal hysterectomy or other gynecologic procedures in patients with narrow vaginal opening, high BMI, prior abdominal surgery, history of cesarean section, and large uteri and can offer better visualization of the pelvic anatomy. A randomized controlled trial of 70 women comparing traditional laparoscopic hysterectomy to vNOTES hysterectomy showed noninferiority in successfully completing the surgery without conversion. However, a meta-analysis comparing vNOTES to multi-port traditional laparoscopy could not be undertaken given the paucity of the studies meeting eligibility. Other advantages of this approach include shorter operative time, hospitalization, and postoperative pain in comparison to traditional laparoscopy. Furthermore, this technique does require an experienced surgeon as there can be technical challenges such as lack of triangulation and overcrowding of instruments when using this route of surgery. Thus, further larger randomized controlled trials are needed.18,19,20

CONCLUSION

Laparoscopic entry is the most important step in performing laparoscopy. The most common entry techniques include Veress, open Hasson, and direct entry as described in this chapter. Complications related to laparoscopy are relatively low, and most of these adverse events are related to initial trocar entry. A large Cochrane review of laparoscopic techniques does not show sufficient evidence to support one method over another or differences in visceral or vascular complications.1 Thus, choice of entry technique and initial trocar placement is dependent on surgeon experience and patient’s characteristics and pathology.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- No consensus statement exists regarding initial abdominal entry and the chosen entry method should be based on surgeon’s preference and patient’s surgical history and characteristics.

- Left upper quadrant entry or Palmer’s technique should be considered in patients with previous abdominal surgery, adhesive disease, or extremes in BMI.

- Entry technique should occur in supine position without any degree of Trendelenburg to avoid vascular, visceral or organ injury.

- Pre-setting intra-abdominal pressure of 25 mmHg for initial trocar entry minimizes risk of vascular and visceral injury.

- Direct entry may be more advantageous over Veress needle for failed entry.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) of this chapter declare that they have no interests that conflict with the contents of the chapter.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

REFERENCES

Ahmad G, Baker J, Finnerty J, et al. Laparoscopic entry techniques. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019;1(1):CD006583. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006583.pub5. PMID: 30657163. | |

Raimondo D, Raffone A, Travaglino A, et al. Laparoscopic entry techniques: Which should you prefer? Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2022. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.14412. PMID: 35980870. | |

Lang T, Pasic RP. Creation of Pneumoperitoneum and Trocar Insertion Techniques. Practical Manual of Minimally Invasive Gynecologic and Robotic Surgery: A Clinical Cook Book 2018;3:43–54. | |

Recknagel JD, Goodman LR. Clinical Perspective Concerning Abdominal Entry Techniques. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2021;28(3):467–74. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2020.07.010. PMID: 32712324. | |

Jain N, Sareen S, Kanawa S, et al. Jain point: A new safe portal for laparoscopic entry in previous surgery cases. J Hum Reprod Sci 2016;9(1):9–17. doi: 10.4103/0974-1208.178637. PMID: 27110072. | |

Ahmad G, Duffy JM, Watson AJ. Laparoscopic entry techniques and complications. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2008;99(1):52–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.04.042. PMID: 17628561. | |

Audebart A, Gomel V. Role of microlaparoscopy in the diagnosis of peritoneal and visceral adhesions and in the prevention of bowel injury associated with blind trocar insertion. Fertility and Sterility 2000;3(3):631–5. | |

Thepsuwan J, Huang K-G, Wilamarta M, et al. Principles of safe abdominal entry in laparoscopic gynecologic surgery. Gynecology and Minimally Invasive Therapy 2013;2(4):105–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gmit.2013.07.003. | |

Alkatout I, Mechler U, Mettler L, et al. The Development of Laparoscopy-A Historical Overview. Front Surg 2021;8:799442. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2021.799442. PMID: 34977146. | |

Theodoropoulou K, Lethaby DR, Bradpiece HA, et al. Direct trocar insertion technique: an alternative for creation of pneumoperitoneum. JSL 2008;12(2):156–8. PMID: 18435888. | |

Aust TR, Kayani SI, Rowlands DJ. Direct optical entry through Palmer’s point: a new technique for those at risk of entry-related trauma at laparoscopy. Gynecol Surg 2010:315–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10397-009-0500-8. | |

Hasson HM. A modified instrument and method for laparoscopy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1971;110(6):886–7. | |

Mac Cordick C, Lecuru F, Rizk E, et al. Morbidity in laparoscopic gynecological surgery: results of a prospective single-center study. Surg Endosc 1999;13(1):57–61. | |

Yuzpe AA. Pneumoperitoneum needle and trocar injuries in laparoscopy. A survey on possible contributing factors and prevention. J Reprod Med 1990;35(5):485–90. | |

Corson SL, Chandler JG, Way LW. Survey of laparoscopic entry injuries provoking litigation. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 2001;8(3):341–7. | |

Chapron CM, Pierre F, Lacroix S, et al. Major vascular injuries during gynecologic laparoscopy. J Am Coll Surg 1997;185(5):461–5. | |

Champault G, Cazacu F, Taffinder N. Serious trocar accidents in laparoscopic surgery: a French survey of 103,852 operations. Surg Laparosc Endosc 1996;6(5):367–70. | |

Nulens K, Bosteels J, De Rop C, et al. vNOTES HYsterectomy for Large Uteri: A retrospective cohort study of 114 patients. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2020;28(7):1351–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmig.2020.10.003. | |

Thigpen B, Sun J, Guan X. Robotic transvaiginal NOTES: A step-by-step approach to surgical technique. Intelligent Surgery 2022;4:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isurg.2022.06.002. | |

Michener CM, Lampert E, Yao M, et al. Meta-analysis of Laparoendoscopic Single-site and Vaginal Natural Orifice Transluminal Endoscopic Hysterectomy Compared with Multiport Hysterectomy: Real Benefits or Diminishing Returns? J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2021;28(3):698–709. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2020.11.029. PMID: 33346073. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards program CLICK HERE)