This chapter should be cited as follows:

Beardmore-Gray A, Chapman A, et al., Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.416503

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Obstetrics Module

Volume 13

Obstetric emergencies

Volume Editor: Dr María Fernanda Escobar Vidarte, Fundación Valle del Lili, Cali, Colombia

Chapter

Management of the Obstetric Patient with Trauma

First published: May 2022

Study Assessment Option

By answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter, readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM.

See end of chapter for details.

INTRODUCTION

In this chapter we discuss trauma in the pregnant patient. Trauma remains a leading cause of maternal mortality and morbidity and is estimated to complicate at least 1 in 12 pregnancies.1

Whilst many of the general principles of trauma management will apply to the pregnant patient, the physiological and anatomical changes of pregnancy present a unique challenge to the healthcare team resuscitating a pregnant patient involved in trauma. There are therefore some key differences in clinical management, which will be outlined in the management section below. When possible, a multi-disciplinary team with both surgical and obstetric experience should be involved in the patient's care.2

The presence of two lives (mother and baby) presents a further challenge to the healthcare team. However, it is important to remember that the best chance of a good fetal outcome depends on optimal management of the mother first.

Learning objectives:

- Understand the etiology of maternal trauma in different settings.

- Develop a systematic method for undertaking a primary survey.

- Understand the key differences in clinical management relating to pregnancy.

- Understand the specific obstetric complications that may occur as a result of trauma.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

There are differences in the epidemiology of trauma in different countries.

In high-income countries such as Canada and the USA, 20% of maternal deaths are directly attributable to injuries.3 The most common causes in these settings are motor vehicle collisions and intimate partner violence, with suicide, falls and burns being other important contributors.1,4,5

There is less data available from low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) but the impact of injury during pregnancy is likely to be even greater in these settings. For example, we know that 85% of fatalities from road traffic injuries occur in LMICs.6 Multiple factors contribute to this statistic including limited use of seatbelts and road traffic safety measures, excessive speeding and high rates of pedestrian injury due to unsafe roadside activities. There is a need for research conducted in LMICs in order to better characterize the burden of trauma in pregnancy in low-resource settings.

Unfortunately, intimate partner violence (IPV) remains widespread and is of global public health concern.7 Up to 71% of women may suffer IPV at some point in their lives, with pregnancy being a particularly high-risk period (30% of domestic abuse starts in pregnancy).8,9 The reported prevalence of intimate partner violence varies, but has been found to be as high as 32% in Egypt, 28% in India, and 21% in Saudi Arabia.10 A further review reported prevalence rates of 23–40% for physical violence during pregnancy among clinical studies in Africa.11 Whilst violence against women transcends religion, education, and socioeconomic circumstances, it is well recognized that poverty and low education rates increase the risk of IPV and it has been reported as the leading cause of injury-related death during pregnancy in multiple LMICs such as Bangladesh, India, Zimbabwe, and Nigeria.12,13,14,15

Intimate partner violence is therefore an important cause of trauma in pregnancy, which should not be ignored. Common injuries may include broken bones, cuts, burns, bleeding, broken teeth, and persistent headaches.16 Direct injury to the abdomen is also common and may precipitate miscarriage and antepartum hemorrhage.16 Any antenatal presentation to hospital presents an important opportunity to screen for domestic abuse of any kind, and women should be asked frequently about whether they feel safe at home, as well as any preventive options they might consider.16

In addition to this, there are high rates of self-inflicted injury reported in many LMICs,13 particularly amongst unmarried women with unplanned pregnancies living in traditionally male-dominated communities where the shame of a pregnancy outside marriage may lead women to attempt either to mechanically induce abortion, or to attempt suicide. This is commonly by violent means, such as hanging or jumping. These injuries unfortunately represent a significant proportion of maternal trauma in these settings and may often involve domestic violence as well, which has been shown to be strongly associated with suicidal ideation.17

Community engagement, education, access to family planning services and robust law enforcement with strong political commitment are all required in order to address the factors contributing to violence against women, which should be prioritized urgently at a national and international level.

INITIAL ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT (THE PRIMARY SURVEY)

Like any emergency, the management of the pregnant trauma patient requires a systematic approach.

Trauma-related deaths can be classified into three main groups:

- Instantaneous: within seconds to minutes of the injury.

- Early: from the first few minutes to a few hours.

- Late: these can occur from a few hours to days or even weeks after the injury.

In this chapter, we will primarily concentrate on the assessment and management of the patient within the first few hours of injury, as it is during this initial phase (often referred to as "the golden hour") that timely interventions can have the greatest impact and prevent potential early deaths. Nevertheless, proper management during this phase will also prevent much of the later morbidity and mortality associated with trauma.

At all times it is extremely important to keep clear and up-to-date notes, recording injuries, key findings, and treatments.

In cases of major trauma, the assessment, stabilization, and care of the pregnant women should be the first priority. Early and effective maternal resuscitation also offers the best chance of a good fetal outcome.

The emergency department is usually the most appropriate place of care during this initial assessment. The first step in any trauma scenario is the primary survey.

The trauma team (this should be a multi-disciplinary team including doctors with experience of obstetrics, trauma and orthopedics and surgery as well as nursing staff) should be called to attend immediately. Access to specialist trauma services may be limited in many low- and middle-income countries. It is therefore critical that all healthcare providers working in these settings have the necessary knowledge and skills to manage the pregnant patient with trauma, whilst working to develop more comprehensive trauma facilities in the future.

A focused history should be taken to establish:

- The mechanism of injury.

- Injuries already identified.

- Symptoms and signs.

- Treatment already received.

N.B. any woman of reproductive age should be assumed to be pregnant unless proved otherwise. Be sure to carry out a pregnancy test on any female trauma patient.

A primary survey should then be undertaken to identify any immediately life-threatening injuries and institute resuscitative measures. As with any patient, this should begin with an assessment of the woman's airway (with cervical spine control), breathing, and circulation.

It is important to remember that vital signs are altered in pregnancy, mimicking early shock. Heart rate is increased 10–15/min from baseline towards the third trimester and blood pressure is 10–15 mmHg lower in the second trimester, returning to normal by term. However, do not be falsely reassured by “normal” vital signs – pregnant women may tolerate up to 1500 ml of blood loss before there is evidence of hypovolemia (this is because blood volume is increased by 50% during pregnancy) therefore close monitoring and active resuscitation is important.

Airway

- Control cervical spine if any suspicion of spinal injury.

- Administer high flow facial oxygen.

Key points in pregnancy:

- In the pregnant patient edematous airways can make intubation more difficult so ensure someone trained in difficult intubation is present (N.B. a laryngoscope with a short/tilted handle may help).

- Delayed gastric emptying in pregnancy increases the risk of aspiration so consider early whether a nasogastric tube is required and use cricoid pressure during intubation.

Breathing

- Assess breathing.

- Identify any life-threatening injuries to the chest (e.g., tension pneumothorax, massive hemothorax, flail chest, or cardic tamponade).

Key points in pregnancy:

- Supplemental high-flow oxygen should be administered as soon as possible to counteract rapid deoxygenation – which occurs more rapidly than in non-pregnant women due to reduced oxygen reserve and a reduced functional residual capacity.

- If a chest tube is required (e.g., in case of a pneumothorax or hemothorax) this should be inserted 1–2 intercostal spaces higher than usual.

Circulation

- Assess capillary refill time, heart rate, blood pressure, temperature, urine output (catheterize).

- Take blood for full blood count, group, and crossmatch.

- Insert two large-bore cannulae into each ante-cubital fossa.

- Commence fluid resuscitation (1–2 l of crystalloid infused rapidly and warmed if possible).

Key points in pregnancy:

- Pregnant women have an increased intravascular volume. They may therefore lose a significant amount of blood (1–2 l) before becoming tachycardic or hypotensive. Do not be falsely reassured by "normal" vital signs. Fetal distress may be evident long before the mother shows any clinical signs of shock.

- Hypotensive resuscitation is not appropriate in pregnancy. Rapid fluid replacement should take place in order to maintain blood volume and perfusion of the feto-placental unit.

- After mid-pregnancy, the woman should be placed in the left lateral tilt position to move the gravid uterus off the inferior vena cava (IVC). This is to prevent supine hypotension and maintain cardiac output. Alternatives include manual displacement of the uterus or achieving left lateral tilt with a spinal board if spinal injury is suspected.

- Vasopressors may decrease placental perfusion leading to fetal hypoxia and should therefore be avoided unless the patient does not respond to adequate fluid resuscitation.

- O-negative blood should be transfused when needed until cross-matched blood becomes available.

Disability

- Assess level of consciousness using the AVPU score: A – alert, V – responsive to voice, P – responsive to pain, U – unresponsive.

- Alternatively, the Glasgow coma scale can be used.

- Check the blood glucose level.

Exposure

- Ensure patient is fully exposed.

- Examine top to toe for any life-threatening injuries (this should include an examination to check for vaginal bleeding).

Key points in pregnancy:

- In a viable fetus, fetal well-being should be assessed once the primary survey has been conducted and the woman is hemodynamically stabilized.

- This should involve fetal heart rate monitoring, ideally with electronic fetal monitoring if available. In women with a high-risk mechanism of trauma (e.g., ejection from a vehicle) or symptoms, such as uterine tendernes, significant abdominal pain, vaginal bleeding, contractions, rupture of membranes, abnormal fetal heart rate pattern, many guidelines advise to continue monitoring for a minimum of 24 h.

RELIEVING AORTOCAVAL COMPRESSION

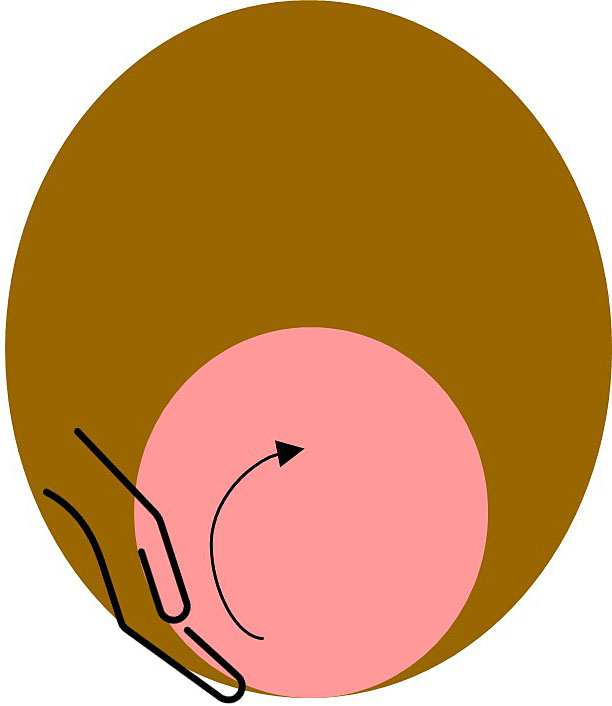

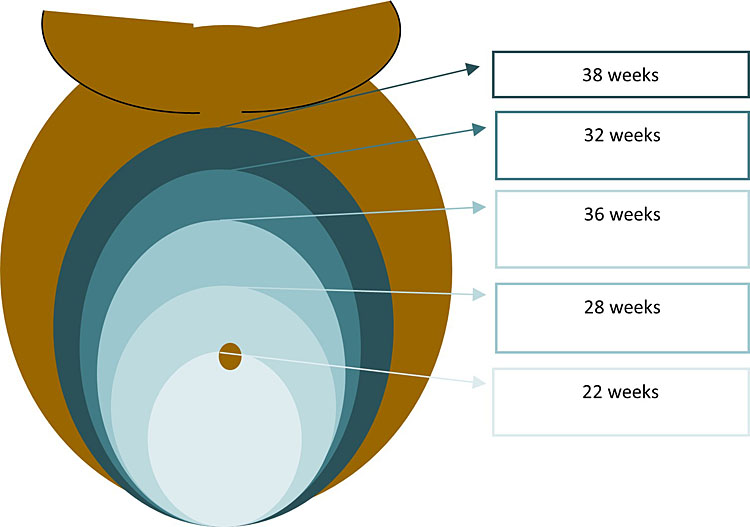

As mentioned above, beyond about 20 weeks of pregnancy (or when the uterus is at or above the level of the umbilicus), it is important to move the gravid uterus off the inferior vena cava to relieve aortocaval compression. This can be achieved via:

- Left lateral tilt.

- Manual displacement of the uterus.

In cases of major trauma, the spine should be protected with a spinal board before any tilt is applied. In the absence of a spinal board, manual displacement should be used.18

A left lateral tilt at an angle of 15–30◦ can be achieved on a tilted operating table, or with a solid wedge and spinal board.

Manual displacement should be achieved by “pushing” the uterus rather than “pulling” it. This technique can be referred to as the “up, off, and over” method. This involves placing a hand below the uterus on the maternal right and pushing the uterus slightly upwards and to the left.

SPECIFIC OBSTETRIC COMPLICATIONS

There are a number of pregnancy-specific complications, which may occur as a result of trauma. These should be examined for, if not already identified.

The three main complications are:

- Placental abruption.

- Uterine rupture.

- Pre-term labor.

Placental abruption

This is the most common cause of fetal death following blunt trauma. As pregnancy progresses, the uterine wall becomes thinner and more elastic. However, the placenta is not elastic and may therefore shear-off as a result of abdominal trauma. It has been reported to occur in up to 50% of cases of major maternal trauma.2 Clinical findings may include abdominal pain, uterine tenderness, uterine contractions, vaginal bleeding, and signs of fetal distress. Importantly, a recent study demonstrated a 50-fold increase in the risk of placental abruption for women presenting following a motor vehicle collision with a “seat-belt sign” (bruising over the dome of the uterus), due to improper placement of the seatbelt (which should be placed low over the anterior pelvis, with the strap above the fundus of the uterus, between the breasts).19 Whilst seatbelts are imperative in preventing adverse outcomes, further awareness regarding their correct placement is needed.

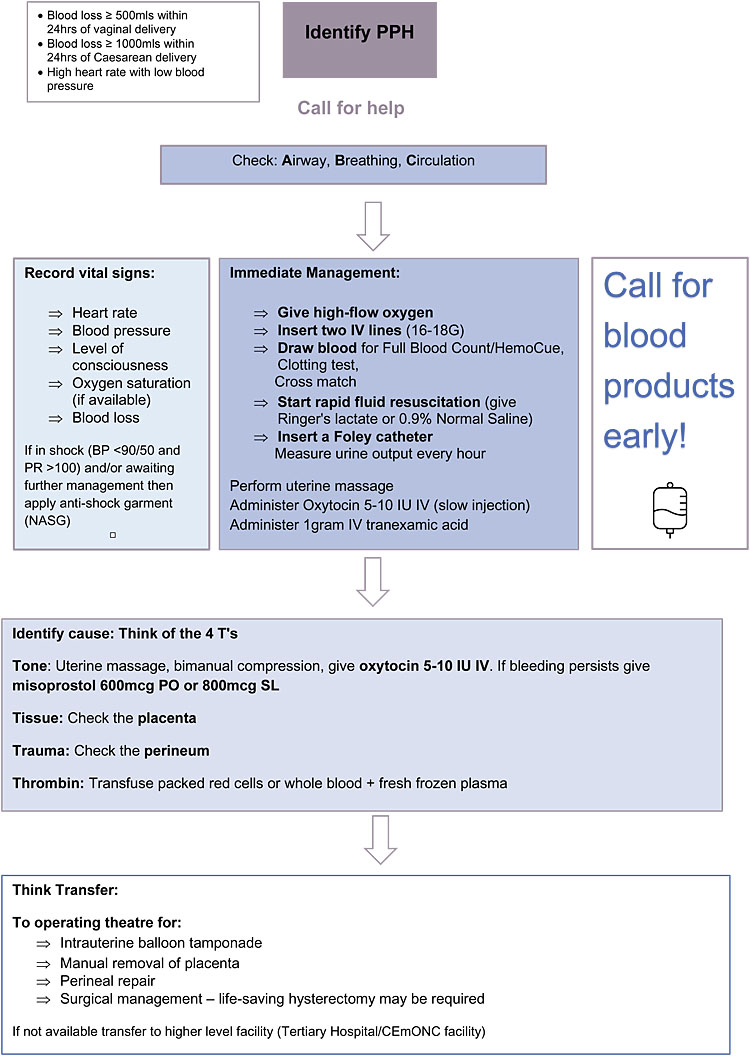

To manage placental abruption, an urgent cesarean section may be required, in order to prevent life-threatening maternal hemorrhage. It is important to be prepared for major obstetric hemorrhage, and to ensure blood products are readily available. Key steps in managing post-partum hemorrhage are highlighted here:

Uterine rupture

This is less common (ocurring in less than 1% of major injuries)2 but should always be considered, particularly in a scarred uterus in the second half of pregnancy. Signs of uterine rupture include abdominal tenderness with guarding and rigidity. In addition there are likely to be signs of maternal shock and fetal distress (including sudden fetal bradycardia). The fetal lie may be transverse or oblique, with easily palpable fetal parts. The management is urgent surgical exploration.

Pre-term labor

This may occur as a direct consequence of placental abruption or direct trauma leading to premature labor. Pre-term rupture of membranes may also occur. Management will depend on the gestational age of the fetus and should involve input from the neonatology team.

In addition to these three main complications, the possibility of an amniotic fluid embolus should always be considered:

Amniotic fluid embolus may occur as a result of trauma to the uterus. This may lead to respiratory compromise, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and subsequent maternal cardiac arrest.

It is important that the Obstetric team are always involved in the management of pregnant trauma patients as their expertise will be essential in recognizing these obstetric complications, which may be unfamiliar to other specialities.

INVESTIGATIONS

Investigations should not delay definitive management and resuscitation. However, they may offer vital information as part of a thorough clinical assessment.

During the primary survey, basic bedside tests (i.e., full blood count, clotting studies, group and save and routine biochemistry) should be carried out as part of the initial work-up.

Radiological investigations should be used when indicated as any effects on the fetus are negligible after 20 weeks' gestation20 and are outweighed by the benefit to the mother.

X-rays of the chest and pelvis should be done as part of the primary survey (bear in mind that the symphysis pubis is physiologically widened in the third trimester). Radiographs of the spine (including cervical spine) should be taken if there is any suspicion of spinal injury.

Ultrasound, particularly FAST (focused abdominal sonography for trauma) scan is safe, non-invasive, and sensitive in diagnosing intra-peritoneal fluid in pregnant patients. It also enables a basic obstetric scan (i.e., to detect a fetal heart rate and locate the placenta) to be performed at the same time. However, a skilled operator is required and therefore hospitals must invest in additional training and equipment for their staff.

CT scanning is the most sensitive and specific investigation for detecting injuries relating to major trauma. Nevertheless, the benefit offered must be weighed against the risk of transferring the patient to a CT scanner. It may be safer to stabilize the patient (and this may include a trauma laparotomy to control major hemorrhage) first and consider a CT scan only once the patient is hemodynamically stable.

In facilities where ultrasound and CT are not available, you may consider diagnostic peritoneal lavage. During pregnancy, this should be performed via a supra-umbilical open approach. The appearance of frank blood, or pink discolouration of the lavage fluid, would suggest intraperitoneal bleeding.

OTHER INJURIES AND THE SECONDARY SURVEY

Once the primary survey is complete, and any life-threatening injuries have been addressed, a secondary survey must be carried out in order to identify any further complications.

This should include a full neurological examination and an examination of the thorax, abdomen, and limbs as well as a review of any radiology investigations already performed. Any limb-threatening injuries (e.g., open fractures, traumatic amputations, neurovascular injuries, and compartment syndrome) should be identified and treated promptly. Do not forget to perform a vaginal examination to assess for any per vaginal bleeding and assessment of the uterus (to check for uterine irritability and contractions).

Traumatic injury can obviously affect any part of the body and may be widespread. Skilled input from other specialities is often therefore required and in general the management would be the same as in the non-pregnant patient.

However, there are some important points relating to the pregnant patient to take note of:

- Suspected spinal injury: The cervical spine should be immobilized using a cervical collar plus blocks on a backboard. The thoracic and lumbar spine should be immobilized on a long spine board. As mentioned above, in the pregnant patient the right hip should be elevated to 10–15 cm with a wedge to avoid supine hypotension and the uterus manually displaced. (N.B. if a pelvic fracture is suspected, it is better to manually displace the uterus without elevating the hip).

- Pelvic fractures in pregnant women can be life-threating to both mother and fetus. During pregnancy, pelvic fractures are more likely to cause massive retroperitoneal bleeding due to tearing of engorged pelvic veins. Immbolization of the pelvis is key in controlling the bleeding, and early involvement of the orthopedic team is essential. It is also important to note that interpretation of pelvic x-rays needs to account for widening of the public symphysis and sacroiliac joints that occurs by the seventh month of pregnancy.

- If the woman has sustained burns of 50% of greater, it is generally advised to deliver if she is in the second or third trimester of pregnancy.5 This is due to the additional demands that continuing the pregnancy would place on the woman's already hypermetabolic state, thus compromising her survival. In addition, no added benefit to the fetus has been found in prolonging pregnancy in this scenario.5

Fetomaternal hemorrhage and alloimmunization

- Anti-D should be given within 72 h to all Rhesus negative women following traumatic injury.

- If it is possible to perform a Kleihauer test, this will aid with quantification of any feto-maternal hemorrhage and whether any additional Anti-D is required.

Perimortem cesarean section

Knowledge of when and how to undertake a perimortem cesarean section (PMCS) may save the life of both the woman and her baby, when performed in the right circumstances.21 In traumatic cardiac arrests, it is important to identify and treat any likely reversible causes, which may differ from causes of a non-traumatic cardiac arrest. This may include intubation and ventilation to reverse hypoxia, chest decompression to treat possible tension pneumothorax, and fluid resuscitation (including blood and blood products) in the case of hypovolemia.21

It must be emphasized that the goal of a perimortem cesarean section is to improve the likelihood of successful resuscitation of the woman. However, prompt delivery of the fetus will also provide the best chance of intact neonatal survival, provided the gestational age is sufficiently advanced (at least above 28 weeks).

When to do a perimortem cesarean section (PMCS)?

When the fundus of the uterus is at or above the umbilicus and therefore large enough to cause aortocaval compression, prompt cesarean section is key to resuscitation in the case of a maternal cardiac arrest.

This is because in pregnant women with aortocaval compression, chest compressions are only able to achieve around 10% of normal cardiac output (compared to 30% in non-pregnant women undergoing cardiopulmonary resuscitation.21 Therefore, delivery of the fetus and placenta improves venous return and cardiac output, increasing the effectiveness of chest compressions and improving the likelihood of successful resuscitation.

If there is no response to CPR within 4 min of maternal cardiac arrest (or if resuscitation is continued beyond this) then PMCS should be undertaken, and ideally be complete within 5 min.18 In practical terms this means that preparations should be made as soon as cardiac arrest is declared and CPR commenced. Hypoxic brain injury to the pregnant woman will begin developing with 4–6 min of cardiac arrest, hence the need to deliver before this point. CPR should be continued throughout. PMCS is a life-saving surgery and should not be delayed.

Where to do a perimortem cesarean section (PMCS)?

A PMCS should not be delayed in order to move the woman to an operating theater; it should take place wherever the cardiac arrest has occurred and the resuscitation is taking place.18

How to do a perimortem cesarean section (PMCS)?

No specific equipment is required, besides a scalpel and two clamps for the umbilical cord. Blood loss will be minimal in view of no cardiac output and no anesthetic is required.18 The individual performing the cesarean section does not need to be an obstetrician. Although a vertical skin incision and classical (vertical) uterine incision are generally recommended as providing the best access, the operator should use whichever approach they are must comfortable with and will enable the quickest access (which may be a transverse skin incision and transverse uterine incision if they are more familiar with this approach).

A short video providing a useful simulation of PMCS can be found here: https://youtu.be/2VyqGqDNlLc.

RESPECTFUL CARE

All women have a right to respectful and compassionate care. This includes the right to privacy, autonomy, informed consent, and affordable access to the best available quality of care, as well as freedom from discrimination and abuse of any kind. It is important that the principles of respectful maternity care (RMC), as outlined by organizations such as the White Ribbon Alliance (www.whiteribbonalliance.org), are maintained even in emergency situations. Healthcare workers should feel supported in delivering RMC and can help to educate and empower women such that they are able to self-advocate, by knowing their own rights and feeling able to make the best decisions for themselves.

CONCLUSION

Trauma remains a significant cause of maternal and fetal mortality around the world, with road traffic accidents and intimate partner violence among the leading causes of injury. These could be prevented by improving road safety measures and protecting women's rights. National governments must prioritize these issues and institute policies to address them as a matter of urgency. The pregnant trauma patient should be assessed and managed in a systematic manner with the support of a multi-disciplinary team. The physiological and anatomical changes that occur during pregnancy need to be taken into consideration and the woman must be assessed for specific obstetric complications. The priority must always be to stabilize and resuscitate the woman, and it may be necessary to deliver the fetus in order to do so. Once the patient has been hemodynamically stabilized, fetal well-being can be assessed and monitored, usually for at least 24 h where there has been major trauma. This chapter has outlined some of the key principles relating to the management of major trauma and highlights the specific issues for the pregnant patient.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- Trauma in pregnancy, and in particular intimate partner violence, remains an urgent and important public health problem.

- A multi-disciplinary team is key in managing trauma in the pregnant woman.

- A systematic approach, incorporating the normal "ABC" principles of resuscitation should be used, but with some important adaptions for the pregnant woman.

- These include ensuring someone trained in difficult intubation is present, administering high-flow oxygen and rapid fluid replacement.

- Beyond 20 weeks of pregnancy, aortocaval compression should be relieved by placing the woman in the left lateral tilt position, or manual displacement of the uterus.

- Examine for specific obstetric complications such as placental abruption and be prepared for major obstetric hemorrhage.

- Do not forget Anti-D if the woman is Rhesus negative.

- In the case of maternal cardiac arrest, perimortem cesarean section should be started if there is no ROSC (return of spontaneous circulation) after 4 min, and ideally completed within 5 min.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) of this chapter declare that they have no interests that conflict with the contents of the chapter.

Feedback

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

REFERENCES

Hill CC, Pickinpaugh J. Trauma and surgical emergencies in the obstetric patient. Surg Clin North Am 2008;88(2):421–40, viii. | |

Jain V, Chari R, Maslovitz S, et al. Guidelines for the Management of a Pregnant Trauma Patient. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2015;37(6):553–74. | |

Kuhlmann RS, Cruikshank DP. Maternal trauma during pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol 1994;37(2):274–93. | |

Weiss HB, Sauber-Schatz EK, Cook LJ. The epidemiology of pregnancy-associated emergency department injury visits and their impact on birth outcomes. Accid Anal Prev 2008;40(3):1088–95. | |

Mendez-Figueroa H, Dahlke JD, Vrees RA, et al. Trauma in pregnancy: an updated systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2013;209(1):1–10. | |

Damsere-Derry J, Ebel BE, Mock CN, et al. Pedestrians' injury patterns in Ghana. Accid Anal Prev 2010;42(4):1080–8. | |

World Health Organisation. World report on violence and health: summary Geneva: WHO, 2002. | |

World Health Organisation. Understanding and addressing violence against women 2012 [Available from: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/violence/en/index.html]. | |

Safe Lives . A Cry for Health: Why we must invest in domestic abuse services in hospitals 2016 [Available from: https://safelives.org.uk/sites/default/files/resources/SAFJ4993_Themis_report_WEBcorrect.pdf]. | |

Campbell J, García-Moreno C, Sharps P. Abuse During Pregnancy in Industrialized and Developing Countries. Violence Against Women 2016;10(7):770–89. | |

Shamu S, Abrahams N, Temmerman M, et al. A systematic review of African studies on intimate partner violence against pregnant women: prevalence and risk factors. PLoS One 2011;6(3):e17591. | |

Shamu S, Abrahams N, Zarowsky C, et al. Intimate partner violence during pregnancy in Zimbabwe: a cross-sectional study of prevalence, predictors and associations with HIV. Trop Med Int Health 2013;18(6):696–711. | |

Fauveau V, Blanchet, T. Deaths from Injuries and Induced Abortion Among Rural Bangladeshi Women. Social Science and Medicine 1989;29:1121–7. | |

Njoku OI, Joannes UO, Christian MC, et al. Trauma during pregnancy in a Nigerian setting: Patterns of presentation and pregnancy outcome. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci 2013;3(4):269–73. | |

Das S, Bapat U, Shah More N, et al. Intimate partner violence against women during and after pregnancy: a cross-sectional study in Mumbai slums. BMC Public Health 2013;13:817. | |

World Health Organisation. Intimate Partner Violence During Pregnancy 2011 [Available from: www.who.int/reproductivehealth]. | |

Devries K, Watts C, Yoshihama M, et al. Violence against women is strongly associated with suicide attempts: evidence from the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence against women. Soc Sci Med 2011;73(1):79–86. | |

Chu J, Johnston TA, Geoghegan J, Royal College of O, Gynaecologists. Maternal Collapse in Pregnancy and the Puerperium: Green-top Guideline No. 56. BJOG 2020;127(5):e14–52. | |

Tracy BM, O'Neal Cm Fau – Clayton E, Clayton E Fau – MacNew H, MacNew H. Seat Belt Sign as a Predictor of Placental Abruption. Am Surg 2017;83(11):452–4. | |

Soni K, Aggarwal R, Trikha A. Initial management of a pregnant woman with trauma. Journal of Obstetric Anaesthesia and Critical Care 2018;8(2). | |

Parry R, Asmussen T, Smith JE. Perimortem caesarean section. Emerg Med J 2016;33(3):224–9. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards program CLICK HERE)