Female Sexual Function

Authors

INTRODUCTION

Sexual behavior, the composite of physiologic, anatomic, and psychosocial factors, is unique in every individual, and therefore, no one definition of sexual behavior is universally accepted. Sexual dysfunction occurs when an individual experiences a disruption in any one of these factors, such as loss of estrogen with menopause, leading to urogenital atrophy and dyspareunia or change in tactile sensitivity from neurologic dysfunction. The path to understanding sexual dysfunction is in establishing a baseline of expected anatomic and physiologic responses to sexual stimulation that occurs in healthy individuals.

| STANDARD SEXUAL RESPONSE |

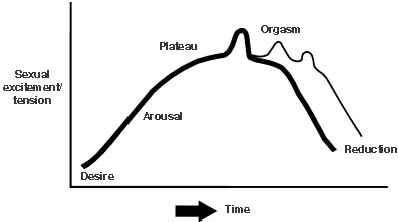

A female’s specific sexual response is affected by her overall physical, hormonal, and psychological health, and therefore, it is difficult to devise a model that can serve as a clinical standard. However, data are available that describe the common anatomic and physiologic changes associated with sexual stimulation. Masters and Johnson were the first to report the four phases of sexual response: namely, excitement, plateau, orgasm, and resolution.1 About 20 years later, Kaplan added an initial excitement phase before arousal commenced (Fig. 1).1,2,3 Concurrent with each phase of sexual response are specific physiologic and anatomic responses.

Excitement, the first phase, begins externally with increased vaginal lubrication from Bartholin’s gland secretions and internally from the engorgement of perivaginal vessels, leading to engorgement and transudation. This overall response plays a key role in a woman’s comfort and sensation during coital activity. In addition, during the excitement phase, extragenital responses include nipple erection, skin flush over the abdomen and breast, tachycardia, increased blood pressure, clitoral enlargement, and vaginal vault expansion. To mark the ending of the excitement phase, the labia majora and minora become fuller owing to vasocongestion, and there is an increase in voluntary and involuntary muscle tension as well as an increase in rectal sphincter contractions.1

Plateau, the second phase, is a continuation of the excitement phase with an increase in vaginal and perineal lubrication and vessel engorgement. Much of this phase is associated with preparing the vagina, cervix, and uterus for vaginal penetration via specific elongation and tenting mechanisms. For instance, the clitoris withdraws under the clitoral hood as the vaginal vault develops a platform from the outer one third of the vagina. These changes serve to increase the width and depth of the vaginal barrel. During this period, the uterus elevates to its fullest capacity, and there is a tenting effect as the cervix elongates. To further prepare the vagina for penetration, Bartholin’s gland continues to secrete lubricating substances, and the vagina, through vasocongestion and transudation, adds to the moisture of the vaginal barrel.

Following the plateau phase, orgasm usually occurs, being brought on by neural recruitment associated with peak sexual stimulation. The orgasm phase is associated with varying degrees of flush, loss of voluntary control of pelvic floor muscle groups, hyperventilation, a further increase in tachycardia and blood pressure, and contractions of the vagina and uterus. Three different types of orgasm in the female have been described: from clitoral stimulation, sexual fantasies, and vaginal penetration without clitoral stimulation. An orgasm in the female is characterized by rhythmic contraction of the pelvic musculature and uterus and, unlike in most men, can recur multiple times during one sexual encounter without a resolution phase because females can move several times from the orgasmic phase back into the plateau phase. As the orgasmic phase dissipates and excitement declines, the phase referred to as resolution occurs.1,2,3 Resolution is the return to normal physiologic function marked by the return to resting blood pressure and heart rate, loss of sexual flush, and the cessation of involuntary muscle contractions.4

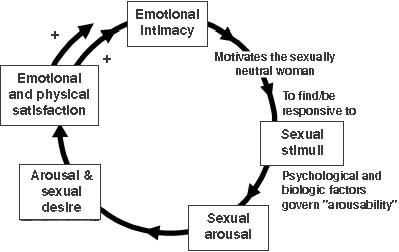

In addition to the traditional sex response cycle proposed by Masters and Johnson, a pathway based on intimacy has been described recently to characterize female sexual response. The new intimacy-based model incorporates the role of emotional intimacy as well as sexual stimuli in the female’s sexual response cycle. In this model, there is a continuum of sexual response rather than a linear one, as described by Masters and Johnson, and the female can enter at any point in the sexual cycle (Fig. 2).5 For example, an emotionally neutral woman can become motivated for coital activity by emotional intimacy, which then enables her to become responsive to sexual stimuli. In this model, once the woman is responsive to sexual stimuli, psychological and biologic factors determine her ability to become aroused and desirous of sexual stimulation. Orgasm may or may not occur, and sexual satisfaction is not completely based on this event.5

The female sexual response cycle, however, may vary not only from woman to woman but also in the same individual over the life cycle. These genital and extragenital reactions of the sexual response are affected by several interrelated systems, including the vascular and endocrine system, sexual health, thoughts, feelings, and emotions.

| SEXUAL DYSFUNCTION |

A woman’s sexuality is a vital part of her being, from which she can derive pleasure, confidence, intimacy, and motherhood. Therefore, if the balance of a woman’s sexual functioning is disrupted, feelings of inadequacy and emotional distress may result. A diagnosis of a sexual disorder is ascertained by taking a thorough sexual history because there are no objective measures other than those used for research for diagnosing a sexual disorder. The accepted definitions of sexual dysfunction are spelled out by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, now in its fourth edition (DSM-IV). The DSM-IV categorizes sexual dysfunctions into four major categories: disorders of desire, arousal, orgasm, and pain. More importantly, the DSM-IV incorporates psychological factors into its analysis of dysfunction.6 The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), a reference developed to classify sexual disorders, is often used in clinical trials and consists of a self-report of 19 items regarding sexual function. The FSFI provides scores on six domains using factor analyses: desire, lubrication, arousal, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain.6

Sexual dysfunction can be classified as primary or secondary. A dysfunction is considered primary if a person has never been able to achieve an adequate sexual response; it is considered secondary if a person at one time had adequate functioning, but then reports inadequate or absent sexual function in all or specific sexual domains.7 In addition to being primary or secondary, sexual dysfunction can be classified as global (occurring with all partners) or situational (occurring with a particular partner).8

Disorders of libido include hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) and sexual aversion disorder (SAD). HSDD is a persistent or recurrent absence or deficiency of sexual fantasies and desire for sexual activity.8 A hypoactive sexual desire can be influenced by chronic illness, lifestyle change, aging, and relationships. The assessment of this disorder is difficult because there are no accepted standards, making the classification of hypoactive sexual desire unique to a woman or to a woman and her partner. Increasing evidence indicates that decreased levels of androgens, especially in surgically menopausal women, as well as hyperprolactinemia may be a cause of HSDD.6 SAD is a phobic aversion to and avoidance of sexual contact with a partner.9 SAD is often psychological in origin and may be the result of past sexual abuse, depression, medication, or severe urogenital atrophy.10,11 In addition, normally functioning women may develop HSDD owing to the use of medications such as antidepressants.12

Sexual arousal disorders are characterized by the inability to achieve or maintain sexual excitement,9 expressed as lack of genital lubrication or swelling response.13 Arousal disorders may be due, in part, to decreased pelvic blood flow14 or estrogen deficiency. Women with arousal disorders may complain of vaginal dryness or decreased sensation in the genitals.9 Currently sildenafil (Viagra) is under investigation for the treatment of female arousal disorders because it has proved to be extremely effective in treating men with similar problems.

Orgasmic disorders are those in which there is a delay or absence of sexual climax or orgasm. This is a fairly common disorder occurring in nearly 25% of the population.10,11 Because lack of coital orgasm is prevalent, it may be considered normal in women who have not been educated regarding the need for clitoral stimulation during coitus. With such education, many women increase their frequency of orgasm.

Pain disorders have been reported by Laumann and coworkers to occur in 14% of women between the ages of 18 and 59 years,10 and include dyspareunia, vaginismus, and the newly classified noncoital pain disorders. Dyspareunia, a general term for coital pain, may occur as a result of an underlying medical condition such as vestibulitis, vaginal atrophy, or infection, or it may be psychological in origin.9 Vaginismus is an involuntary reaction of the pelvic musculature to attempted vaginal penetration. Often, a woman with vaginismus can become quite frustrated with her inability to perform sexually. Lastly, noncoital sexual pain disorder consists of genital pain with noncoital sexual stimulation, which may be reported in women with vulvodynia.

| SOCIETAL ISSUES |

External influences define distinct areas regarding what types of sexual activity are acceptable and what types are unacceptable. For instance, in today’s society, acceptable sexual behavior is seen as serial monogamy between two consenting adults, whereas an example of unacceptable sexual behavior is an extramarital sexual liaison. In addition to the clear-cut, defined standards of sexual behavior, there is a vast gray area that can be viewed as normal or abnormal. This gray area pertains to many sexual parameters such as what is “normal” sexual frequency, that is frequency of coitus, frequency of orgasm, and frequency of self-stimulation. Whereas statistics are helpful in describing the gray areas of societal norms, they do not describe individual varieties of the norm. Therefore, a degree of objectivity and understanding is essential when clinicians are dealing with sexual dysfunction because one person’s sexual dysfunction may be another person’s normal sexual function. Generally, the acceptable norms of sexual response become “abnormal” when a person (or at times a partner) is unhappy or dissatisfied with her sexual functioning.15

A major controversy regarding society’s sexual norms of what is classified as healthy sex function versus what is pathologic is the area of sexual preference. Homosexuality is commonly stigmatized in almost all cultures. In addition, homosexuals may not feel like legitimate members of society because they do not have the same marriage and insurance rights as heterosexuals. Not surprisingly, because homosexuals are often viewed as social deviants and are not seen as equal to their heterosexual counterparts, they have a high prevalence of depression.16 Mental illness and depression can lead to decreased sexual desire and inadvertently can affect sexual function. Therefore, when counseling a homosexual, it is critical for physicians to take these issues into account and evaluate whether or not they can objectively treat this patient or whether they should refer the patient to someone who can.

A woman’s sexual identity is influenced by many factors that evolve over the course of her life. Different variables such as religion, current events, and societal views may affect how comfortable a woman is with her sexuality. For instance, some religions teach women that the only purpose for sexual activity is to procreate, and it is only deemed appropriate if one is married. Sexual activity for the purpose of pleasure or intimacy may be associated with feelings of guilt or shame, and this may affect a woman’s sexual function. Also, in religions and cultures in which a woman is taught to play a submissive role, it is unlikely to hear her complain about not being sexually satisfied. In addition to religious inhibitions, many people may fear sex because of its close association with the current human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/sexually transmitted disease epidemic. During the 1960s and 1970s a sexual revolution, due to the introduction of oral contraceptives into everyday life, took place and couples could engage in coital activity without the fear of an unwanted or unplanned pregnancy. As a backlash to these uninhibited sexual undertones that existed until the 1980s, currently another sexual revolution is taking place. The new sexual revolution is based on the fear of acquiring a sexually transmitted disease (currently referred to as a sexually transmitted infection [STI]) and limiting sexual freedom for many. It has been reported that, in the United States 15 million STIs occur annually, making these a major public health problem.17 Widespread infections in the United States include chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, genital herpes, human papillomavirus (HPV), hepatitis B, trichomoniasis, bacterial vaginosis, HIV, and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), with HPV of the cervix and vagina being the most common STI among the younger, sexually active population.17 Therefore, attitudes have changed about the acceptance of being able to choose partners for the sole reason of sexual exchange. Many women associate fear of contracting an STI with sexual activity, thus, this has a negative impact on their sexuality. Women with AIDS or other STIs have to take precautions to prevent the spread of disease to their partner and, if pregnant, their fetus. For example, women with genital herpes may not be able to engage in intercourse during outbreaks. Psychologically, the impact of an STI on a woman may be enormous because she may have fear of contaminating her partner and her unborn children. These feelings may lead to a diminished desire to engage in sexual intercourse. Women with STIs should be counseled on how to have safe sex and to discuss any inhibitions or fears they may be feeling about sex.

Societal views also play a role in a woman’s perception of herself as a sexual being. Society often views an aging woman as sexually unattractive and sexually retired. As women lose the ability to procreate, they may be viewed as asexual and are not expected to desire or enjoy sex. This image is further perpetuated by society viewing the elderly as “functional children,” an attitude that strips them of their sexuality.18

| MENOPAUSE |

Menopause is a time of great hormonal, anatomic, and physiologic change for women. Among the many changes that occur is a diminution in sexual function for many aging women. Changing sexual function is due to a variety of factors, one most notably being estrogen and androgen decline. There is no clinical outcomes–based model that defines how a woman’s sexuality will change with the onset of menopause; therefore, a more holistic approach is needed to examine all aspects that contribute to a woman’s changing sexual function. Some factors that affect sexual function are the psychological impact of aging, whether menopause was surgical or natural, the rate at which one transitioned into menopause, religion, cultural and social factors, medical illness, and availability of a sexual partner.19 In addition, data will often be difficult to analyze owing to the varying definitions of sexuality; some data define sexual activity exclusively by coital activity whereas others view it as sexual thoughts, fantasies, desires, or masturbation.20

Most women tend to have their own preconceived ideas about how menopause will affect their sexuality, and these ideas may be emotionally troubling for some. The obvious changes associated with aging, such as wrinkling, sagging skin, and weight gain, may alter a woman’s perception of her sexual self causing her to feel less attractive and feminine.21 In addition, relationship issues and altered hormonal status may adversely affect the way a woman feels about her sexuality.

Of the many physiologic changes that take place with the onset of menopause, an especially significant one is a decrease in vaginal blood flow owing to a decrease in estrogen levels. As functional follicular depletion occurs, there is a drop in endocrine functioning of the ovaries, which results in a decrease in estrogen secretion. Postmenopausal women often have difficulty with vaginal lubrication and arousal as a result of the atrophic changes in the vaginal and clitoral vasculature.22 With diminished vasculature, there is decreased blood flow to the reproductive organs. Decreased gonadal estrogen levels have several other effects on the vagina, uterus, urinary tract, and sexual functioning. Among the many changes that occur in addition to vaginal dryness are vulvovaginal pruritus, loss of vaginal elasticity, vaginal vault thinning, and vaginal barrel shortening.23 The rugae of the vagina also becomes more friable and easily damaged, leading to petechiae, dyspareunia, and bleeding.23,24 The urinary tract is also affected, and complaints of an increase in urinary urgency and frequency, recurrent urinary tract infections, and urogenital atrophy are frequently voiced by older women.23 Other pelvic changes are numerous, including cervical atrophy, decreased mucous secretion,25 and decreased uteral contractility; and the vaginal platform is not as readily established, which may result in a decreased libido.26,27 The uterus also becomes atrophic and fibrotic as it is deprived of estrogen and may undergo painful muscle spasms that worsen during orgasm.28 In addition, vaginal relaxation can create an uncomfortable pressure-like feeling, which may decrease sexual sensation and lessen the ability to enjoy coitus.28 The hypoestrogenic state has, in addition to urogenital changes, global changes. Because breast tissue becomes less sensitive, there is a decrease in swelling and erection of the nipple. Studies performed by Bachmann and associates suggest that a greater number of sexual dysfunction complaints occur in women over the age of 50 years, and that this age group has sex less frequently, although a small percentage of postmenopausal women report an increase in sexual interest and enjoyment.28,29 In addition to affecting sexual function, a hypoestrogenic state is also responsible for sleep disturbances and changes in temperature regulation in menopausal women.

One treatment that helps to alleviate some of the adverse symptoms are experienced in a hypoestrogenic state is estrogen replacement therapy (ERT). ERT alleviates vaginal dryness, vasomotor symptoms, and insomnia. ERT also improves urogenital integrity and helps to provide a general sense of well-being. It may also serve as a protective factor against cognitive decline in the elderly. Although ERT has not been shown to directly increase sexual drive, it may improve sexual functioning through its positive physiologic effects.19 Whereas ERT has many benefits, it may lead to an increased risk of endometrial; therefore, an estrogen and progesterone combination should be used in high-risk individuals.23

Androgen with estrogen replacement may also be useful in the management of menopausal women with sexual dysfunction. In addition to estrogen release, the ovaries play an important role in regulating the circulation of testosterone (an androgen).30,31 Women that undergo natural or surgical menopause have been shown to have decreased levels of testosterone. Testosterone affects sexual desire, bone density, muscle mass and strength, adipose tissue distribution, mood, energy, and psychological well-being.32 In addition, testosterone may work synergistically with estrogen for the relief of vaginal dryness and vasomotor symptoms.32 Androgen replacement in an environment of adequate estrogen is correlated with an increase in psychological functioning. This may result in greater sexual satisfaction owing to the association between well-being and sexual function.32,33 Shifren and colleagues demonstrated that transdermal testosterone in combination with oral ERT is associated with improved sexual functioning and emotional well-being.34 As with estrogen, there are risks associated with androgen therapy. Potential side effects include acne, weight gain, excess facial and body hair, emotional changes, and adverse lipid profile changes. Based on available data, these side effects usually do not occur if the supplemental androgen levels are maintained within physiologic ranges.32

| MEDICATION |

Drug use can have an adverse effect on sexual response. A decrease in desire is often noted with the usage of antilipids, antipsychotics, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, beta blockers, clonidine, danazol, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), lithium, indomethacin, spirolactones, tricyclic antidepressant (TCAs), and antireflux agents. Diminished arousal can be seen with alcohol, anticholinergics, antihistamines, antihypertensives, benzodiazepines, SSRIs, TCAs, and monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Orgasmic dysfunction is associated with the use of methyldopa (Aldomet), amphetamines, antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, SSRIs, TCAs, narcotics, and trazodone9 (Table 1).35 Medications should be withdrawn if problems develop with sexual function. If these medications cannot be substituted, it is helpful to discuss the potential side effects and explore options for dealing with any developing problems.

TABLE 1. Common Drugs That Affect Sexuality in Women

Decreased Desire

Antilipid medications

Antipsychotics

Barbiturates

Benzodiazepines

Beta blockers

Clonidine

Danazol

Digoxin

Fluoxetine

Gonatropin-releasing hormone agonists

H2 blockers and antireflux agents

Indomethacin

Ketoconazole

Lithium

Phenytoin

Spironolactone

Tricyclic antidepressants

Diminished Arousal

Alcohol

Anticholinergics

Antihistamines

Antihypertensives

Benzodiazepines

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors

Tricyclic antidepressants

Orgasmic Dysfunction

Aldomet

Amphethamines and related anorexic drugs

Antipsychotics

Benzodiazepines

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

Narcotics

Trazadone

Tricyclic antidepressants*

*

Also associated with painful orgasm.

Adapted from Weiner DN, Rosen RC: Medications and their Impact. In Sipski ML, Alexander CJ (eds): Sexual Function in People With Disability and Chronic Illness, pp 856–1118. Gaithersberg, MD, Aspen Publishers, 1997.

| CHRONIC ILLNESS |

Medical illnesses can influence sexual function in numerous ways. For instance, decreased sexual frequency is often found in patients who have suffered from a heart attack, with some reports showing that as many as 40% to 58% of recovering patients abstain.23 This decrease in intercourse may be due to medication, anxiety, depression, fear of coital death, dyspnea, and angina.23 Similar findings are seen in patients afflicted with diabetes, hypertension, chronic pain, arthritis, and cancer. In males, diabetes is associated with erectile dysfunction due to atherosclerotic changes. It is speculated that similar changes in women may result in similar problems, although it has not yet been proved.20 Chronic pain can also lead to sexual dysfunction by affecting mood, physical ability to perform, and desire for intercourse. Arthritis sufferers may also be affected because arthritis is often associated with decreased flexibility and pain, adding to coital discomfort. Cancer and gynecologic malignancy may cause devastating psychological and physical trauma for the patient and their partner, resulting in diminished sexuality. Many women with malignancies may develop sexual problems, and it was found that 30% of patients did not resume engaging in sexual intercourse in a 6-month follow-up period after a mastectomy.36 The disfigurement that can result from the treatment of these malignancies, whether it is from chemotherapeutic agents that cause excessive weight loss and alopecia, or actual surgical procedures, can be quite traumatizing for a patient. Therefore, a woman’s self-perception can be adversely affected, making her feel unattractive, thus, limiting her desire to have sex. A study undertaken by Gamel and associates examined the effects of gynecologic cancer on sexuality and the mode of intervention that may be useful in caring for these patients. It was proposed that sexual functioning should be evaluated prior to and following surgery and that the nurse who routinely cares for the patient should serve as a counselor regarding sexual functioning.37 Although these topics may be difficult to discuss, it is the responsibility of the physician to address or make certain that the issue of sexuality as it pertains to all patients is addressed.

| HYSTERECTOMY |

Postoperative sexual dysfunction is common because anxiety, fears, and diminished activity levels all frequently occur following surgical procedures. Hysterectomy, mastectomy, and gynecologic malignancy surgeries are the most common procedures for women to undergo in the gynecologic setting. Hysterectomies may have varying effects on a woman, depending on her age and life experience.38 For example, a hysterectomy performed on a young woman who has not had any children or has not completed her family will have different consequences than a hysterectomy performed on a postmenopausal woman who has completed her family and is not desirous of future pregnancy. There are psychological factors to take into account because many woman associate their uterus with femininity and womanhood. Much controversy surrounds the actual impact of a hysterectomy on sexual function. Virtanen and coworkers36 noted an improvement in dyspareunia and sexual desire with no effect on orgasmic capability following hysterectomy, whereas Darling and colleagues39 reported a decrease in sexual responsiveness in 33% to 37% of women who underwent the procedure. To further complicate the issue, there is concern over the role that the cervix plays in sexual function and whether leaving it intact may be beneficial to some women. Currently, the role of the nervous system on sexual function is not fully understood; therefore, elucidating the effects of a hysterectomy, which will affect the integrity of the nervous system, is difficult.

| MASTECTOMY |

Mastectomy is another procedure associated with a diminished sexual response. Women who have undergone mastectomies may feel more sexually inhibited than they did prior to their operation. The alteration to one’s body may have a large impact on how one feels about their partner seeing them undressed. A practical way that patients often adjust to these changes regarding physical disfigurement and intimacy is to wear camisoles or nightwear to conceal the scar of surgery.40 Currently, surgeons are moving away from performing disfiguring operations when applicable and offering reconstructive surgery as an option.20 Because these procedures are seen as diminishing a woman’s femininity, careful guidelines and definitions need to be established when evaluating the relationship between sexual dysfunction and malignancy.

| SEXUALLY DYSFUNCTIONAL PARTNER |

As women age, the frequency of sexual dysfunction increases. It is important to take into account all factors that can be associated with a woman’s functioning, including the availability of a partner. Aging men also encounter health issues, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and arthritis, that may affect their desire and ability to perform. The incidence of erectile dysfunction greatly increases as erections become less firm, the refractory period lengthens, and ejaculations become less forceful.19 Men may also suffer from premature ejaculation, which may interfere with their partner’s ability to reach orgasm. Women may view their partner’s dysfunction as their fault because their own feelings of inadequacies may prevail. For this reason, it is imperative for a couple to maintain open communication and to realize that the changes they are experiencing can be managed. Equally important is the readjustment of sexual expectations to include other forms of intimacy such as kissing, cuddling, and manual stimulation.19 In addition, sildenafil citrate (also known as Viagra) is a great new option available to assist men who suffer from erectile dysfunction, thus making sexual activity possible.6

| PREGNANCY AND POSTPARTUM |

Generally, sexual intercourse throughout one’s pregnancy is considered safe and should not predispose a woman to preterm birth unless there is an existing complication such as placenta previa, abruptio placenta, or premature rupture of membranes.41 During pregnancy, sexual activity may be limited by exhaustion, by discomfort owing to the growing fetus, or from the fear of either partner that they will harm the fetus. Postpartum sexual activity usually resumes in about 6 weeks; however, some women experience sex problems even after this time period. Research has indicated that of 1249 women surveyed, the median time to restart coitus is 6 weeks after birth and that 53% of those women had difficulties in sexual functioning within the first 8 weeks. Women who experienced problems cited perineal pain, excessive fatigue, and lack of sexual interest as the cause.42,43 Also, the degree of perineal damage and the use of instruments that can cause tissue damage, such as forceps and extraction vacuums, were noted to significantly increase the risk of postpartum dyspareunia.44 In addition, women who deliver their children vaginally are at greater risk for pelvic floor injury.45 This injury can lead to incontinence and dyspareunia. To alleviate these symptoms, pelvic floor exercises are suggested. Pelvic floor, or Kegel, exercises serve to strengthen vaginal and rectal musculature. As well, women who breastfeed their children tend to exhibit a diminished desire for sex, possibly owing to hyperprolactinemia, amenorrhea, or a decrease in estrogen, progesterone, and androgen levels. Because of the high frequency of postpartum sexual dysfunction, physicians should incorporate routine sexual health discussions into the postpartum follow-up procedure. Pregnant woman need to be educated about the changes occurring in their bodies and how these changes will affect their sexuality during and after their pregnancy. In addition, a physician should discuss options that their patient has during delivery, such as whether a woman wants an episiotomy during labor. Studies indicate that having an episiotomy may increase the risk of sexual dysfunction; therefore, alternate methods should be explored to prevent this from occurring.44

| INTERVENTION AND TREATMENT |

The key to intervention and treatment is the proper diagnosis of sexual dysfunction, which is achieved by taking a thorough medical history. An evaluation of medical conditions, habits, comorbid diseases and an assessment of menopausal symptoms, if present, are essential to a woman’s medical history. This should be followed by a careful physical examination to determine vaginal health and evaluate for atrophy, vulvar dystrophies, and vaginitis. A detailed examination should further include assessing the epithelium, skin elasticity, turgor, rugae, labial fat content, presence of dyspareunia, and introitol size.46 In addition, a quantitative assessment of vaginal health can be performed by using the Vaginal Health Index. The Vaginal Health Index is a system used to evaluate vaginal elasticity, fluid volume, pH, epithelial integrity, and moisture on a scale of 1 to 5 (Table 2).47 If dyspareunia exists, a complete history of the pain, including location, severity, quality, timing of onset, and association with bodily functioning, should be taken. Whereas this type of pain is often difficult for woman to localize, a physician should help the patient to answer by asking open-ended questions.8 Furthermore, a sexual functioning history should be taken and should include areas of general health, such as endocrine, neurologic, surgical, and degenerative functions; psychiatric history, including depression, bipolar tendencies, and anxiety; psychological and interpersonal factors, such as past sexual trauma, relationship issues, and partner problems; drug use, both recreational and prescription; and a hormonal status evaluation.8 From this examination, a diagnosis can be obtained and intervention, if possible, can be made to address the woman’s problems.

TABLE 2. Vaginal Health Index

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

Elasticity | None | Poor | Fair | Good | Excellent |

Fluid volume (pooling of secretions) | None | Scant amount, vault not entirely covered | Superficial amount, vault entirely covered | Moderate amount of dryness (small areas of dryness on cotton-tip applicator) | Normal amount (fully saturates on cotton-tip applicator) |

pH | ≥6.1 | 5.6–6.0 | 5.1–5.5 | 4.7–5.0 | <4.6 |

Epithelial integrity | Petechiae noted before contact | Bleeds with light contact | Bleeds with scraping | Not friable, thin epithelium | Normal |

Moisture (coating) | None, surface inflamed | None, surface not inflamed | Minimal | Moderate | Normal |

Bachmann GA, Notelovitz M, Kelly SJ, et al: Long-term nonhormonal treatment of vaginal dryness. Clin Pract Sex, 8:12, 1992.

Perimenopausal and menopausal women can be offered a variety of interventions. Education and counseling prior to menopause should be available so that women may alter any negative, self-made notions that they may have about menopause. The four R-’s—reframe, reeducate, refocus, and refresh—are useful in guiding intervention strategies.19 Reframing the situation to explain how the upcoming events may affect sexual functions can bring reassurance to perimenopausal woman. Reeducation deals with providing pertinent information on the topic of sex and other related issues such as vulvar hygiene to women. Refocusing involves redirecting the patient to place emphasis on areas that they can control and improve on, instead of focusing on the problem. Refreshing teaches women to utilize other expressions of intimacy to gain satisfaction when activities they previously engaged in are no longer pleasurable or possible.19 Medical interventions are also valuable for menopausal woman. These medical interventions include hormone replacement therapy, testosterone supplementation, and vaginal dilators.20

Various sexual dysfunctions can be handled by realizing what the patient is struggling with and then making the appropriate recommendations. Every effort to localize, classify the source of the problem, and treat sexual disorders should be attempted because they are common phenomena. Some libido disorders can be addressed with estrogen and androgen replacement therapy. Orgasm disorders can be successfully treated by group, individual, or couple therapy. Other treatment options include vaginal creams that serve as lubricants or estrogen cream rings or tablets that alleviate complaints associated with vaginal atrophy and dryness. Vaginal dilation, physical and psychological therapy, as well as TCAs may be useful in alleviating vaginal pain disorders.8 In addition, studies are currently going on to evaluate the usefulness of sildenafil in treating women with sexual arousal disorders because it has such a profound effect on improving male sexual function.6 It may also be useful for a patient to be evaluated by a sex therapist prior to a medical examination to assess the emotional and psychological state that is affecting her sexual performance. Additionally, an approach that includes the sexual partner is often useful, regardless of the type of female sexual dysfunction48 because sexual dysfunction affects one’s partner as well.

Self-esteem, well-being, and pleasure are just a few things that a woman gains from being confident in her sexuality. Therefore, a sexual disorder can have devastating effects on a woman’s emotional state. A woman may associate a sexual disorder with the inability to become intimate with her partner, which may lead to dissatisfaction in a relationship. Consequently, it is imperative that the clinician be equipped with all the tools necessary to diagnose and treat a sexual disorder. In addition, further studies need to be performed to expand the limited knowledge of sexual disorders currently available. Hopefully, these studies will make available more treatment options for women with sexual dysfunctions.

REFERENCES

Masters W, Johnson V: Human Sexual Response. Boston, Little, Brown & Co, 1966 |

|

Sadock BJ, Kaplan MI, Freedman AM: The Sexual Experience. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1976 |

|

Kaplan HS: The New Sex Therapy. London, Bailliere-Tindall, 1974 |

|

Sarrel P: Sexual physiology and sexual functioning. Postgrad Med 3:157, 1980 |

|

Basson R: Female sexual response: The role of drugs in the management of sexual dysfunction. Obstet Gynecol 98:350, 2001 |

|

Meston C, Frohlich P: Update on female sexual function. Curr Opin Urol 11:6, 2001 |

|

Bjorksten O: The physiology of sexual response and classification of sexual dysfunction. In Sciarra JJ (ed): Gynecology and Obstetrics. Vol 6:Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1983 |

|

Seltzer VL, Pearse WH: Women’s Primary Health Care Office Practice and Procedures. 2nd ed.. New York, McGraw-Hill, 2000 |

|

Levy B: Break the Silence—Discussing sexual dysfunction. Obstet Gynecol Management 14:3, 2002 |

|

Laumann EO, Gagnon JH, Michael RT, et al: The Social Organization of Sexuality: Sexual Practices in the United States. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1994 |

|

Rosen RC, Taylor JF, Leiblum SR, et al: Prevalence of sexual dysfunction in women: Results of a survey of 329 women in an outpatient gynecologic clinic. J Sex Marital Ther 19:3, 1993 |

|

Meston C, Frohlich P: The neurobiology of sexual function. Arch Gen Psychiatry 57:11, 2000 |

|

Baty P: Is sildenafil an efficacious treatment for sexual arousal disorder in premenopausal women? Fam Pract 50:11, 2001 |

|

Sommer F, Caspers HP, Esders K, et al: Measurement of vaginal and minor labial oxygen tension for the evaluation of female sexual function. J Urol 165:4, 2001 |

|

Munjack D: The recognition and management of desire phase sexual dysfunction. In Sciarra JJ (ed): Gynecology and Obstetrics. Vol 6:Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1983 |

|

Gilman S, Cochran S, Mays V: Risk of psychiatric disorders among individuals reporting same-sex sexual partners in the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Public Health 91:6, 2001 |

|

Cates W: Estimates of the incidence and prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases in the United States. Sex Transm Dis 26:4, 1999 |

|

Dunn ME, Umlauf RL, Mermis BJ: The rehabilitation situations inventory: Staff perception of difficult behavioral situations in rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 73:4, 1992 |

|

Lobo RA, Kelsey J, Marcus R: Menopause Biology and Pathobiology. San Diego, CA, Academic Press, 2000 |

|

Lobo RA: Treatment of the Postmenopausal Woman: Basic and Clinical Aspects. 2nd ed.. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1999 |

|

Leiblum SR: Sex—Midlife and Beyond. American Fertility Society Postgraduate Course: Sexual Dysfunction: Patient Concerns Practical Strategies Orlando, FL, 1991 |

|

Park K, Goldstein I, Andry C, et al: Vasculogenic female sexual dysfunction: The hemodynamic basis for vaginal engorgement insufficiency and clitoral erectile insufficiency. Int J Impot Res 9:1, 1997 |

|

Lobo RA (ed): Treatment of the Postmenopausal Woman. New York, Raven Press, 1994 |

|

Semmens JP, Semmens EC: Sexual function and the menopause. Clin Obstet Gynecol 27:3, 1984 |

|

Van Blerkom J: The influence of intrinsic and extrinsic factors on the developmental potential and chromosomal normality of the human oocyte. J Soc Gynecol Invest 3:1, 1996 |

|

Roughan PA, Kaiser FE, Morley JE: Sexuality and the older woman. Clin Geriatr Med 9:1, 1993 |

|

Masters W, Johnson V: Sex and aging process. J Am Geriatr Soc 29:9, 1981. |

|

Bachmann GA, Leiblum SR, Hayman HN: Sexual expression during the climactic years. Sex Med Today 9:2, 1985 |

|

Sherman B, Korenman S: Hormonal characteristics the human menstrual cycle throughout reproductive life. J Clin Invest 55:4, 1975 |

|

Judd HL: Hormonal dynamics associated with the menopause. Clin Obstet Gynecol 19:4, 1976 |

|

Hughes CL Jr, Wall LL, Creasman WT: Reproductive hormone levels in gynecologic oncology patients undergoing surgical castration after spontaneous menopause. Gynecol Oncol 40:1, 1991 |

|

Bachmann G, Bancroft J, Braunstein G, et al: Female androgen insufficiency: The Princeton consensus statement on definition, classification, and assessment. Fertil Steril 77:4, 2002 |

|

Greendale GA, Hogan P, Shumaker S: Sexual functioning in postmenopausal women. J Women’s Health 5:5, 1996 |

|

Shifren JL: Androgen deficiency in oophorectomized women. Fertil Steril 77(Suppl. 4):4, 2002 |

|

Weiner DN, Rosen RC: Medications and their impact. In Sipski ML, Alexander CJ (eds): Sexual Function in People with Disability and Chronic Illness. pp 856, 1118 Gaithersberg, MD, Aspen Publishers, 1997 |

|

Virtanen H, Makinen J, Tenho T, et al: Effects of abdominal hysterectomy on urinary and sexual symptoms. Br J Urol 72:6, 1993 |

|

Gamel C, Micheil H, Bryn D: Informational needs about the effects of gynecological cancer on sexuality: A review of the current literature. J Clin Nurs 9:5, 2000 |

|

Sloan D: The emotional and psychosexual aspects of hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 131:6, 1978 |

|

Darling CA, McKay J, Smith YM: Understanding hysterectomies: Sexual satisfaction and quality of life. J Sex Res 30, 1993 |

|

Hordern A: Intimacy and sexuality for the woman with breast cancer. Cancer Nurs 23:3, 2000 |

|

Kurki T, Ylikorkola O: Coitus during pregnancy is not related to bacterial vaginosis or preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol 169:5, 1993 |

|

Glazner CMA, Abdalla MI, Stroud P, et al: Postnatal maternal morbidity: Extent , causes, and treatment. Br J Obstet Gynecol 102:4, 1995 |

|

Glazner CMA: Sexual function after childbirth: Women’s experiences, persistent morbidity and lack of professional recognition. Br J Obstet Gynecol 104:3, 1997 |

|

Signorello LB, Harlow BL, Chekos AK, et al: Postpartum sexual functioning and its relationship to perineal trauma: A retrospective cohort study of primiparous women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 184:5, 2001 |

|

Delancey J, Schaffer J, Brubaker L: Pelvic floor injury—is it inevitable? Obstet Gyencol Management 13:10, 2001 |

|

Davis SR, Burger HG: Clinical Review 82: Androgens and the postmenopausal woman. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 81:8, 1996 |

|

Bachmann GA, Notelovitz M, Kelly SJ, et al: Long-term nonhormonal treatment of vaginal dryness. Clin Pract Sex 8:8, 1992 |

|

Berman JR, Berman LA, Werbin TJ, et al: Female sexual dysfunction—anatomy, physiology, evaluation, and treatment options. Curr Opin Urol 9:6, 1999 |