This chapter should be cited as follows:

Oken E, Glob Libr Women's Med

ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.421563

Nutrition in the Periconceptional, Pregnancy and Postpartum Periods

Volume Editor:

DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.00000

Chapter

Food insecurity, environmental toxicants and nutrition: effects on reproduction and pregnancy

VIDEO 3

Nutrition plays a major role in healthy pregnancy and development of the fetus. In addition, nutrition can expose humans to a wide range of potentially hazardous environmental constituents, such as organic pollutants and heavy metals from marine or agricultural food products while processing, producing and packaging.

Food insecurity, a condition in which households lack consistent access to sufficient, nutritious food, is a significant public health issue affecting millions globally.

The USA’s Department of Agriculture (USDA)1 defines food security at the household level, in which high food security indicates consistent access to sufficient food for an active, healthy life, and food insecurity encompasses households that experience uncertainty about their food supply due to insufficient resources. Food-insecure households are further classified into those with low food security and those with very low food security, with the latter experiencing disruptions in eating patterns and reduced food intake.

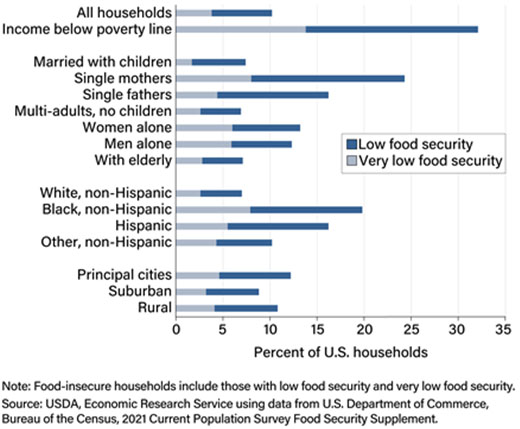

In the USA, approximately 10% of households experience some degree of food insecurity, with higher rates observed among low-income households, single-parent families, and those from non-white racial and ethnic backgrounds (Figure 1). Although food insecurity is a global issue, its prevalence is especially high in regions facing conflict, climate change and poor governance. The World Health Organization (WHO) highlights the complex interplay of poverty, inequality, conflict, and climate change as key drivers of food insecurity, particularly in vulnerable populations.

1

Rates of food insecurity among segments of the population in the USA.

Food insecurity influences maternal and child health through several interrelated pathways, including poor nutrition, exposure to environmental toxins, and heightened psychosocial stress. Structural factors such as financial instability and discrimination in marginalized communities contribute to food insecurity by limiting access to nutritious food, especially in areas with fewer markets offering healthy options. This situation often results in diets that are low in essential nutrients and high in processed foods, which not only lack nutritional value but also contain endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) like phthalates and phenols. These chemicals are found in food packaging and preparation methods and can negatively affect both maternal and child health.

The poor diet resulting from food insecurity can contribute to inflammation and endocrine disruption, leading to adverse pregnancy outcomes such as hypertensive disorders, gestational diabetes and excessive weight gain during pregnancy. These factors also increase the risk of long-term health issues for both mother and child, including obesity, metabolic disorders and chronic conditions later in life.

One study2 involving 268 mothers showed that food insecurity during pregnancy was associated with a threefold increased risk of preterm birth and higher odds of hospitalization and missed immunizations for infants. Furthermore, food-insecure mothers faced greater levels of social needs in pediatric care settings, indicating that food insecurity is often linked with broader socioeconomic challenges.

At the neighborhood level, areas with low food access and high poverty, often referred to as "food deserts", create environmental conditions that further exacerbate food insecurity. In a study of over 22 000 pregnant individuals, researchers found that residence in low-income, low-access (LILA) neighborhoods was associated with lower birth weight and suboptimal fetal growth, even after adjusting for individual sociodemographic factors3. However, when race and ethnicity were accounted for, these associations weakened, highlighting the intertwined nature of food insecurity and racial inequities.

A 2024 meta-analysis of 25 studies examining food insecurity and pregnancy outcomes found no significant associations between household food insecurity and small- or large-for-gestational age4. However, food insecurity was linked to increased rates of Cesarean delivery, as well as mental health issues such as anxiety, depression and high stress levels. These psychological factors likely interact with other adverse effects of food insecurity to further harm maternal and child health.

One seemingly paradoxical finding is the association between food insecurity and obesity, particularly in developed countries. Another 2024 meta-analysis found that food insecurity is associated with a 50% increased risk of obesity5. While food insecurity might imply insufficient food intake, it is more likely that food-insecure individuals consume diets that are low in nutrient-dense foods and high in ultraprocessed foods, which contribute to weight gain. Studies also show that food-insecure individuals often have a high intake of sugary, packaged and fast foods, which are not only low in nutritional value but also contribute to systemic inflammation and metabolic dysregulation.

Despite the challenges of measuring diet quality across different studies, research consistently shows that food-insecure individuals tend to have poorer dietary patterns, including reduced consumption of fruits and vegetables and increased intake of processed meats and sugary snacks. This unhealthy diet pattern contributes to the increased risk of obesity, gestational weight gain issues and other pregnancy-related complications.

Food insecurity also heightens exposure to environmental toxins, particularly chemicals found in food packaging. Individuals experiencing food insecurity are more likely to rely on shelf-stable, packaged foods that expose them to harmful substances such as phthalates, bisphenol A (BPA), and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS)4,6. Research has shown that food-insecure individuals have higher levels of these contaminants in their bodies, which can adversely affect both maternal and fetal health.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, food-insecure individuals were also found to exhibit poorer food-handling behaviors, including reduced handwashing and increased use of cleaning agents on food, further exacerbating potential risks from both infection and chemical exposure7.

It is crucial to acknowledge that food insecurity often intersects with other environmental risks, particularly those linked to race. Non-white racial and ethnic groups are disproportionately exposed to environmental hazards such as poor air and water quality, contaminated housing and occupational hazards, which compound the negative effects of food insecurity. Structural racism, therefore, plays a significant role in perpetuating both food insecurity and environmental health disparities.

Given the widespread nature of food insecurity and its profound impact on maternal and child health, it is essential to implement policies and interventions aimed at reducing poverty and improving access to nutritious foods. Healthcare professionals should screen for food insecurity and refer patients to appropriate food assistance programs and social services.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Author(s) statement awaited.

REFERENCES

USDA ERS – Key Statistics & Graphics [Internet]. [cited 2022 Oct 21]. Available from: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-u-s/key-statistics-graphics/ | |

Sandoval VS, Jackson A, Saleeby E, Smith L, Schickedanz A. Associations Between Prenatal Food Insecurity and Prematurity, Pediatric Health Care Utilization, and Postnatal Social Needs. Acad Pediatr. 2021 Apr;21(3):455–461. PMCID: PMC8026536. | |

Aris IM, Lin PID, Wu AJ, Dabelea D, Lester BM, Wright RJ, Karagas MR, Kerver JM, Dunlop AL, Joseph CL, Camargo CA, Ganiban JM, Schmidt RJ, Strakovsky RS, McEvoy CT, Hipwell AE, O’Shea TM, McCormack LA, Maldonado LE, Niu Z, Ferrara A, Zhu Y, Chehab RF, Kinsey EW, Bush NR, Nguyen RH, Carroll KN, Barrett ES, Lyall K, Sims-Taylor LM, Trasande L, Biagini JM, Breton CV, Patti MA, Coull B, Amutah-Onukagha N, Hacker MR, James-Todd T, Oken E, program collaborators for Environmental Influences on Child Health Outcomes, ECHO components – Coordinating Center, Data Analysis Center, Person-Reported Outcomes Core, ECHO Awardees and Cohorts. Birth outcomes in relation to neighborhood food access and individual food insecurity during pregnancy in the Environmental Influences on Child Health Outcomes (ECHO)-wide cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2024 May;119(5):1216–1226. PMID: 38431121. | |

Bell Z, Nguyen G, Andreae G, Scott S, Sermin-Reed L, Lake AA, Heslehurst N. Associations between food insecurity in high-income countries and pregnancy outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2024 Sep;21(9):e1004450. PMCID: PMC11386426. | |

Nguyen G, Bell Z, Andreae G, Scott S, Sermin-Reed L, Lake AA, Heslehurst N. Food insecurity during pregnancy in high-income countries, and maternal weight and diet: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2024 Jul;25(7):e13753. PMID: 38693587. | |

Shiue I. People with diabetes, respiratory, liver or mental disorders, higher urinary antimony, bisphenol A, or pesticides had higher food insecurity: USA NHANES, 2005–2006. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2016 Jan;23(1):198–205. PMID: 26517997. | |

Thomas MS, Feng Y. Food Handling Practices in the Era of COVID-19: A Mixed-Method Longitudinal Needs Assessment of Consumers in the United States. J Food Prot. 2021 Jul 1;84(7):1176–1187. PMCID: PMC9906159. |

Online Study Assessment Option

All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can automatically receive 1.5 Continuing Professional Development points plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering four multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about the Continuing Professional Development awards program CLICK HERE)